Inside Out

Where should you look for your next CEO?

Based on research by Robert E. Hoskisson (George R. Brown Emeritus Professor of Management), Shih-chi Chiu, Richard A. Johnson and Seemantini Pathak

Where Should You Look For Your Next CEO?

- When companies plan to restructure, it makes a difference if the new CEO is hired from inside or outside.

- Companies that value sheer volume of asset divestures may want a leader from inside the firm.

- Companies seeking a slimmer, more focused, less diversified operation may want a CEO from outside.

Star Co. is a hot mess. The business is bloated and sprawling. Its stock is tanking. Profits are down. It’s clearly time for a new CEO.

But where to look — inside the company or outside? It’s a decision every restructuring company faces.

Cenovus Energy tapped an outsider in 2017. General Electric, the same year, went with a longtime insider. Though it’s too soon to know yet for sure, which one likely made the right choice?

Rice Business emeritus professor Robert E. Hoskisson, with coauthors Shih-chi Chiu, then at Nanyang Technological University (now at the University of Houston), Richard A. Johnson of University of Missouri, Columbia and Seemantini Pathak of University of Missouri-St. Louis, set out for an answer: Where is the best place for a restructuring company to get its next CEO?

According to conventional wisdom and some past research, change is more likely under an outside CEO. He or she can start fresh, armed with a greater mandate to shake things up.

Recent evidence, though, suggests that outsiders may actually have more trouble succeeding. That’s because they lack the institutional knowledge to make the most informed choices, and the existing relationships needed to ease change with minimal pain. Insiders, this research shows, have the advantage of key “firm-specific” knowledge on everything from customers to suppliers to workforce composition.

To pin down an answer on whether it’s better to stay inside or go outside, Hoskisson’s team decided to look at corporate divestiture — asset sales, spinoffs, equity carve-outs — as a proxy for overall strategic change. (It’s already well documented that a new CEO makes organizational changes such as personnel changes and culture shifts.)

Next, they distinguished between scale and scope. The scale of a divestiture reflects magnitude: How many units were sold? The scope reflects diversification portfolio adjustment: Does the company have fewer business lines?

Focusing on 234 divestitures at U.S. firms that voluntarily restructured between 1986 and 2009, the authors defined a new inside CEO as having been in that role two or fewer years, and with the company previously for more than two years. They defined a new outside CEO as someone who had been at the company for a maximum of two years in any role.

Heading into the analysis, the researchers expected they would reach different conclusions for scale vs. scope. And the results were just that.

New inside CEOs, they found, did carry out more divesture activities than new outside CEOs. Not having as much inside knowledge, the outside CEO was more likely to prefer a simpler divesture plan, one that didn’t require evaluating each unit or asset. Instead, the professors hypothesized, an outsider was more likely to follow investors’ general preferences about firm strategy.

“When a higher magnitude of corporate divestures is required, internal successors are more astute than external successors in accomplishing this objective,” the researchers write. On the other hand, when a company wants to shrink the diversified scope of a business portfolio, “external successors are more likely to bring their firms to a more focused position.”

The researchers also suggested future lines of study about new CEOs and strategic change. What happens when firms want to buy and sell at the same time? Does the CEO selection process itself affect restructuring scale and scope? And does an inside chief executive who won a power struggle against a predecessor perform differently than an inside CEO named in orderly succession planning?

In the meantime, the findings are clear. If your corporate board is hunting for a new CEO, it may pay to go for the fresh face. But depending on your goals, your best option may also be a top executive sitting at a desk a few steps away.

Robert E. Hoskisson is the George R. Brown Emeritus Professor of Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Chu, S., Johnson, R., Hoskisson, R., & Pathak, S. (2016). The impact of CEO successor origin on corporate divestiture scale and scope. The Leadership Quarterly, 27, 617-633.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Full-Court Press

How did one court decision transform corporate ownership in America?

Based on research by Alan Crane and Andrew Koch.

How Did One Court Decision Transform Corporate Ownership In America?

- In 1999, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals cut back shareholders’ ability to file class action lawsuits.

- Small shareholders lost a key tool to monitor and control firm management.

- As a result, the ownership structure of firms across the West Coast changed dramatically – with institutional investors taking on an outsized ownership role.

Accounting misstatements, insider trading, withholding of material information about firm operations — all are good reasons for a class action suit. Suing as a class lets small shareholders aggregate their individual strengths.

So what happens when these suits get harder to file? From the shareholders’ perspective, it means less ability to join forces. But how does decreased ability to file class action suits affect how firms do business?

Rice Business professor Alan Crane spent years studying how the ability to litigate affects firm ownership. In a recent paper he coauthored, he analyzed firm ownership structures after a 1999 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling reduced small shareholders’ power to file class action suits.

The Ninth Circuit covers the West Coast, Alaska and Hawaii. This means that the court’s decision altered the path of the thousands of firms throughout the region that argued that small shareholders were abusing the class action mechanism with frivolous lawsuits.

Naturally, the decision meant a decline in class action litigation: a 43 percent drop over the following year. Crane, however, was less interested in caseloads than in the firms’ ensuing ownership structures. To understand the outcomes of the ruling, he and his coauthor looked at a large sample of firms over several years before and after the 1999 ruling.

The average cost of a successfully settled class-action lawsuit, the authors knew, is roughly $13 million. Given the average damages and settlements size, a single individual would need to own approximately 10.4 percent of the average firm to find an individual suit worth filing.

So what happened next? Firms that once had significant numbers of small shareholders, the authors found, suddenly were taken over by institutional investors. In 1995, institutional ownership in the 9th Circuit versus other parts of the U.S. was roughly equal. But by 2010, some 11 years after the Ninth Circuit decision, the level of institutional ownership in Ninth Circuit firms increased to roughly 70 percent. Compare this with the 50 percent institutional ownership for comparable firms outside of the court’s jurisdiction.

Ownership concentration and the number of large owners per firm also increased, by 15% and 14% respectively, relative to their 1998 averages.

Not all firms became dominated by institutions in equal measure. Large institutions were lured by firms likely to pay out significant dividends. Hence, firms that didn’t offer the potential for such payouts failed to attract the same level of institutional interest.

Whether institutional ownership is good or bad for a company is a separate issue, the authors noted. Institutions, after all, have a great deal of bargaining power, allowing them to force management into efficiencies it may not otherwise want.

But one outcome was clear. Owners’ ability to keep management in line with threats of class action drastically diminished. The Ninth Circuit’s stated rationale for its decision was limiting the impact of frivolous class action suits. But its effect, Crane found, was widespread change in ownership structure — even in companies uninvolved in litigation.

The implications were subtle but important. Contrary to the court’s argument, the lawsuits the professors studied did *not* appear overall to be frivolous. Yet the Ninth Circuit’s ruling led to profound changes in ownership structures. The takeaway: Class action suits, contrary to many previous findings, are in fact a governance tool.

One court decision, in other words, was enough to transform firm ownership up and down the West Coast. As a result, the power of the class action lawsuit — one of the most effective checks on corporate management of businesses — was slashed. The court’s decision may have saved time and money lost to isolated, frivolous lawsuits. But for countless shareholders and consumers, it was an unintended gamechanger.

Alan Crane is an associate professor of finance at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

For further information please see: Crane, A. & Koch, A. (2018). Shareholder Litigation and Ownership Structure: Evidence from a Natural Experiment. Management Science, 64(1), 5-23.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

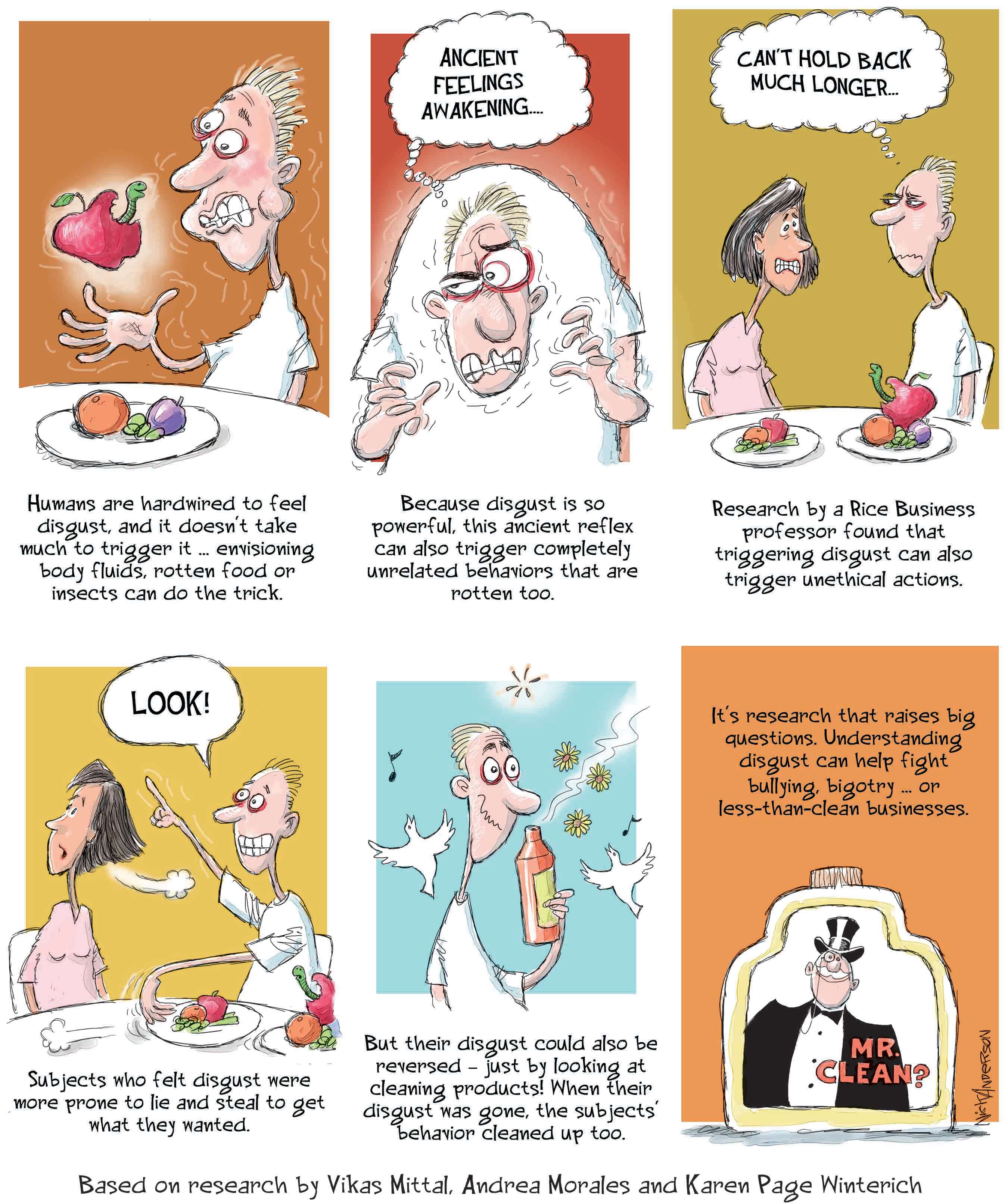

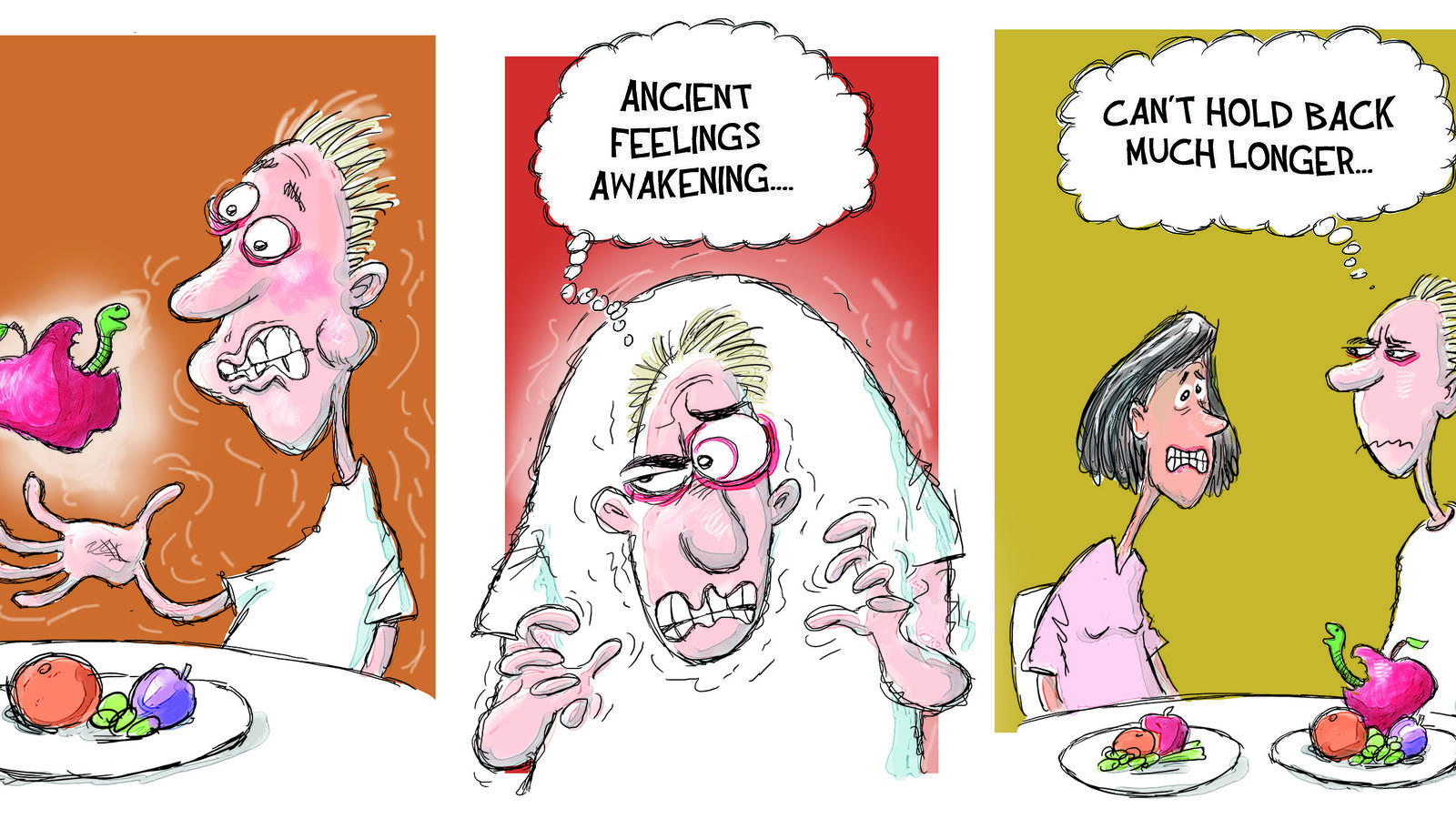

Despicable Me

How creating a sense of disgust can unleash bad behavior.

Illustrated by Nick Anderson. Based on research by Vikas Mittal, Andrea Morales and Karen Page Winterich.

How Creating A Sense Of Disgust Can Unleash Bad Behavior

Want to learn more about how disgust prompts bad behavior? Read our article Clean Living.

Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist Nick Anderson depicts research by Rice Business professor Vikas Mittal.

Mittal, V., Morales, A. & Winterich, K. P. (2014). Protect thyself: how affective self-protection increases self-interested behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 125(2), 151-161.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Nick Anderson is a Pultizer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Object Of My Affection

What happens when a brand we know (or think we know) and love turns out to be something altogether different?

By Jennifer Latson

What Happens When A Brand We Know (Or Think We Know) And Love Turns Out To Be Something Altogether Different?

Some brands feel like old friends. Take Newman’s Own, which donates its profits to charity, or Patagonia, whose environmental activism has won the admiration, and the patronage, of many Americans — even if we find their parkas pricey.

Brands like these earn our loyalty by appealing to our better natures. They make us feel good about ourselves when we support them. For some of us, buying a Newman’s Own product is the emotional equivalent of helping out our beloved, stunningly blue-eyed, uncle.

But when beloved brands do wrong, it can be as devastating as being betrayed by Uncle Paul. And some of America’s best-loved companies and public figures have done a lot of wrong lately.

Many of us were shocked when Volkswagen’s “clean diesel” technology turned out to be mere smoke and mirrors — and when the CEO of Audi, Volkswagen’s parent company, was arrested in 2015, it drove home the disconnect between the brand’s reputation and reality.

Nike, meanwhile, earned our affection with ads empowering female athletes — such as the 2007 billboard featuring Serena Williams, tennis racket in hand, asking, “Are you looking at my titles?” Those of us who bought into their brand messaging were dismayed to hear that Nike’s female employees faced some of their toughest challenges at work, where, as the New York Times reported in April of 2018, women who reported being harassed and routinely marginalized were largely ignored.

And then there are the famous figures whose actions belie their wholesome public persona. When Bill Cosby was convicted in April of 2018 of drugging and sexually assaulting a woman — one of more than 50 who’ve accused him of similar crimes — it marked the final stage of his transformation, in the public’s eye, from father figure to predator. For those of us who grew up watching “The Cosby Show,” reconciling the Cosby brand with his true identity has been a heartbreaking struggle.

Why should we take it so personally when companies or celebrities fail to live up to their own branding?

“One of the reasons brands are so powerful is that their connections strengthen over time, becoming deeply embedded in our minds,” writes Tim Calkins, a marketing professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. “In many cases, our belief in a brand can supersede reality. We are quick to forgive brands we trust.”

Our unwillingness to question brands we’ve come to admire is dangerous, Calkins argues: It’s the reason Cosby escaped justice for so long, despite the mounting evidence of his misdeeds. Few of us could believe that “America’s Dad” would behave so despicably — so we didn’t. At least, not until the evidence became impossible to ignore, well beyond the point where we would have believed similar allegations against a lesser-known figure.

“The reason Cosby’s conviction is so notable is that it highlights the disconnect between his brand image and reality. The funny, casual Cosby isn’t real. It is an image that he created,” Calkins writes.

But the image that good branding creates becomes so firmly embedded in people’s minds that it’s virtually impossible to shake, says Utpal Dholakia, a marketing professor at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business. Even revelations of hypocrisy by a brand behemoth like Nike — in the form of marginalizing female employees while pouring millions into messaging that empowers female athletes — aren’t enough to knock it off its pedestal.

“That’s why the branding is so important. The consumer’s connection is with the brand, and not the people behind the brand,” Dholakia explains. “I’m not saying it’s good or bad, but that’s the effect it has. That’s why we spend so much money on advertising and establishing brand messaging.”

The ability of good branding to overcome bad publicity was perhaps most apparent when beloved Texas brand Blue Bell issued a series of ice cream recalls in 2015 after listeria outbreaks killed three people and sickened others.

“Each time, they would take their products off the shelves and then relaunch them,” Dholakia says. “And people were thrilled to go out and buy those products again. Every time.”

Blue Bell’s brand appeal, built on a marketing campaign that emphasized its small-town roots, was enough to keep its customers loyal despite the threat of illness. For many consumers, supporting the brand was a way to identify as a true Texan. Blue Bell, they felt, was in their blood.

Successful brands really do become part of our sense of self, writes Hilary Jerome Scarsella, who is completing a PhD in theological studies at Vanderbilt University. Scarsella ascribes to psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut’s theory that selfhood develops in response to other people and things, using the term “cultural selfobjects” to describe those that form a vital part of selfhood for an entire group of people — as Cosby did in American culture.

“Bill Cosby long represented an image of fatherhood, family and upper middle-class life that both reflected and shaped what Americans valued, understood themselves to be, and saw as possible for their lives. In this way, he became part of the American self,” Scarsella wrote in a recent essay.

“As a cultural selfobject, Cosby’s acts of violence against individual women were also a betrayal for all those who built a part of themselves in response to the values he mirrored back to them,” Scarsella explains. “Because cultural selfobjects shape who we are, this betrayal and loss is profound. It results in a loss of a part of our own selves.”

The revelations that Nike executives mistreated female employees, however, don’t seem to have evoked a similarly profound sense of loss. In fact, according to YouGov BrandIndex, a service that tracks the public’s perception of brands, Nike experienced a sharp but short-lived drop in consumer perception just after stories emerged about its toxic workplace — and has since rebounded to its previous levels.

While it seems like taking the moral high ground would give brands farther to fall when they do wrong, the opposite is actually true, says Dholakia. That’s because the more powerful and persuasive your branding is, the better insulated you are from bad publicity.

“In marketing, we call it the brand insulation effect: The stronger the brand, the more impervious it is to these occurrences,” Dholakia says.

But good branding has its limits, as Cosby’s fall from grace reveals. Individual reputations are easier to tarnish than the multifaceted brand identities. Nike’s reputation doesn’t hinge entirely on empowering women, after all. But when your brand rests exclusively on being America’s Dad, it’s impossible to recover from the damage of doing something egregiously un-dad-like, Dholakia says.

“Once your reputation gets hurt, it’s hurt. That’s all Cosby has: his reputation,” he says. “It’s not a brand that has many offshoots.”

Even for large brands, however, it can be hard to bounce back from a scandal that compromises your core identity. That’s where good damage control comes in — and the best takes the form of honesty, transparency, and sincere contrition, explains Scott Davis, chief growth officer at Prophet, a brand and marketing consultancy.

Starbucks offers another example. In April of 2018, two black men were arrested at a Philadelphia Starbucks store after an employee called the police because they used the bathroom without buying anything. For a company that has worked for years to build a reputation as “an inclusive, progressive, forward-thinking beacon of a brand,” the incident could have dealt a devastating blow, Davis wrote in an essay for Forbes.

But Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson handled it the way you’d expect a good leader — or a good friend — to do when they’ve let you down.

“He accepted accountability for the incident, acknowledged that Starbucks must do better and apologized to all that were impacted by this incident but, in particular, to the two men who suffered this incredible indignity,” Davis writes. “He promised change and did not kick the can down the road.”

Researchers have found that, paradoxically, doing wrong and then making it right can actually strengthen the relationship between a company and its customers — just as it can between friends. These are defining moments in any relationship, and just as a betrayal by a close friend can end the friendship, it can also be an opportunity for growth and reconciliation.

In fact, Dholakia argues, we tend to be quicker to forgive a brand that lets us down than, say, an uncle.

“People are not all that forgiving of individuals,” he says. “But brands are powerful. People are extremely loyal to brands.”

Jennifer Latson is a writer and editor at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business and the author of The Boy Who Loved Too Much, a nonfiction book about a rare disorder called Williams syndrome.

Never Miss A Story

You May Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Loose Lips Sink Ships

Is there a way to stop institutional leaks?

Based on research by Prashant Kale, Kannan Srikanth, Anand Nandkumar, and Deepa Mani

Is There A Way To Stop Institutional Leaks?

- Specific workflow patterns can help offshore R&D centers keep a tighter grip on intellectual property.

- Spreading information widely within the company while limiting the depth of any one person’s knowledge makes leaks less damaging.

- Even inherently risky projects can be well secured with these techniques.

Offshoring has its tradeoffs. With their lower labor costs and growing talent pool, India and China entice many multinational corporations to launch research and development (R&D) centers. But both countries have weak patent enforcement regimes, which can expose companies to the pilfering of intellectual property. Highly mobile offshore employees and all-but-unenforceable non-compete agreements add to the risk. If today's employee heads to a rival company tomorrow, secrets are likely to leak.

For the parent company, the biggest worry is the leak of widely applicable new technology. When innovation is the product of a company's overall body of knowledge, a single leak can erode a firm’s entire competitive position. The stakes rise further when a process or product is fully documented, making it easier to create a competing product from scratch.

Luckily, managers of offshore R&D centers can limit their risk, according to Rice Business professor Prashant Kale and three colleagues. In a 2015 study of offshore R&D centers in India, the team identified six organizational mechanisms to help keep corporate secrets safe.

All six were based on two principles: 1) Minimize the leakable information; and 2) ensure that anything that does reach your competitors is of little use to them.

To measure how common these mechanisms were, Kale’s team surveyed managers of 142 Indian R&D centers in the energy, pharmaceuticals, semiconductor, IT hardware and software sectors.

The first practice the scholars identified: Break down the R&D division's knowledge base into interlocking fragments, like parts of a jigsaw puzzle. Distribute a large share of the puzzle pieces to workers at the home location.

Second, stress interdependence. Projects executed at headquarters should depend heavily on activities at offshore locations, and vice versa. Third, managers should tie R&D knowledge to specific assets within the company. By doing so, they help guarantee that a rival company without these assets won’t be able wring much value out of leaked knowledge.

By the same token, the fourth practice is to give headquarters control over project selection, design, implementation and/or operations. Fifth, relay key, substantive information from headquarters to the offshore location – and do it often. Using this mechanism, executives who spot a good idea can blend it with complementary knowledge from other locations. The mix makes an idea both more valuable and harder to copy.

Finally, set up internal controls so no single person has all the information a rival needs to copy an innovation. This could mean storing critical data in more than one database, controlling access to that data, placing protected servers elsewhere or even assigning employee teams to separate, restricted-access work spaces.

Each of these six measures, the researchers found, boosts worker dependence on the system as a whole and arranges a company's institutional knowledge into more complex patterns. Competitors who get hold of leaked information won’t get much out of it if they can’t understand the components of a process and how they all fit together.

None of the respondents had adopted all six safeguards, Kale and his team noticed. Nevertheless, most companies who used one or more of these strategies reported confidence that their intellectual property was secure. They could have been mistaken, of course. But the researchers chose to use high confidence levels as a proxy for successful intellectual property security, explaining that objective data “on the extent of actual leakage … are notoriously hard to obtain.”

Interestingly, the managers’ confidence also changed the way their firms did business. Emboldened by their sense of security, Kale found, many firms in the study took on riskier projects and, in some cases, chose to hire more personnel.

Risk, the homily says, goes hand in hand with opportunity. For offshore enterprises that manage that risk intelligently, the opportunities can benefit both parent firm and local hires abroad.

Prashant Kale is associate professor of strategic management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Srikanth, K., Nandkumar, A., Kale, P., & Mani, D. (2015). The role of organizational mechanisms in preventing leakage of unpatented knowledge. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 1206.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

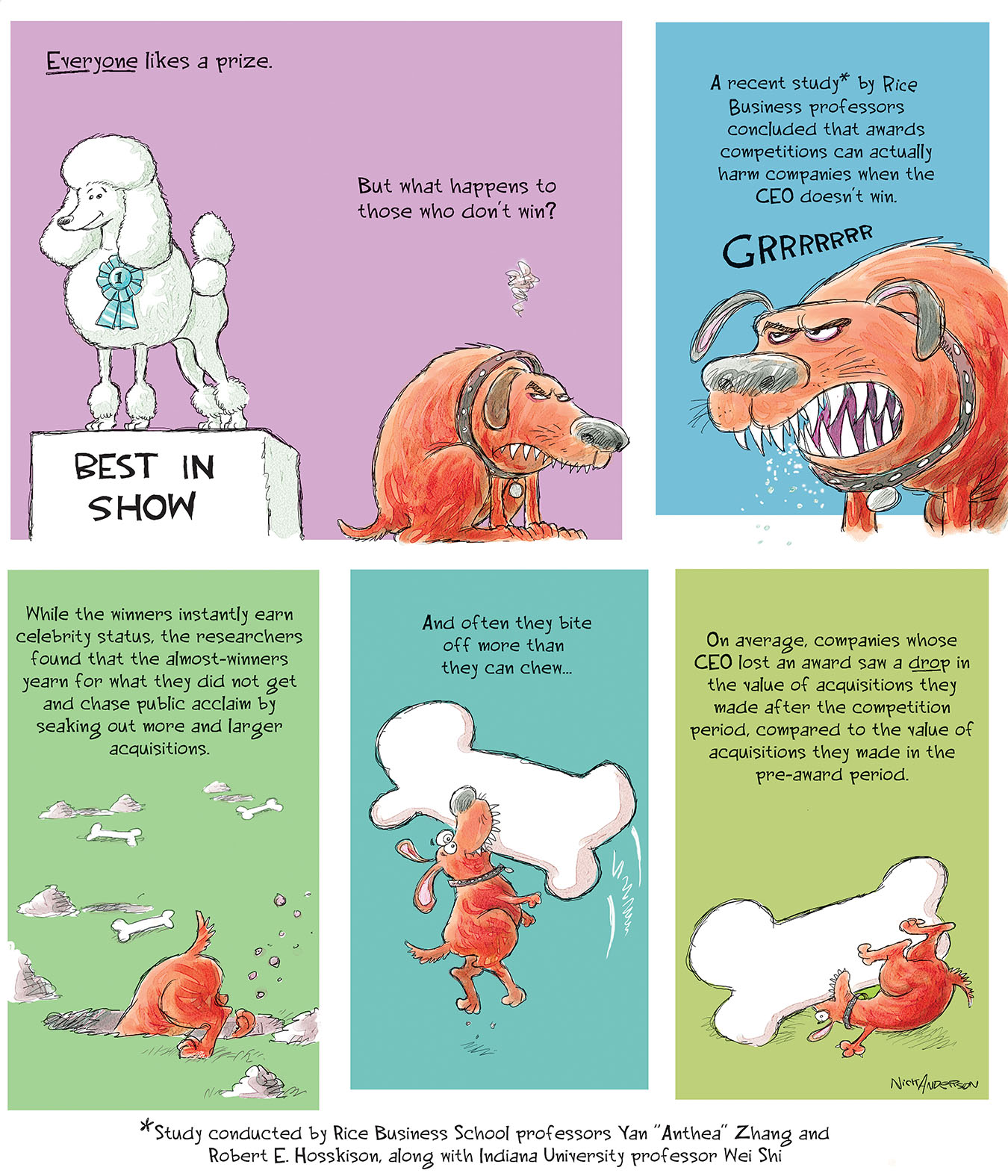

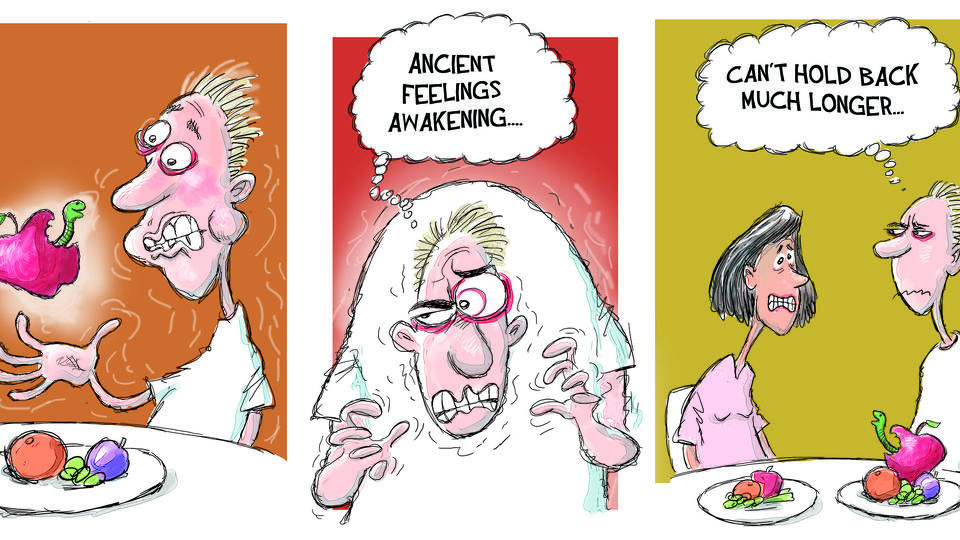

Chasing Their Tails

What happens to shareholders when a CEO fails to be named top dog?

Illustrated by Nick Anderson. Based on research by Yan Anthea Zhang, Robert E. Hoskisson and Wei Shi.

What Happens To Shareholders When A CEO Fails To Be Named Top Dog?

Want to learn more about why losing can lead CEOs to take risks? Read our article Sore Losers.

Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist, Nick Anderson depicts the troubling results of a study by Rice Business professor Yan Anthea Zhang and Robert E. Hoskisson.

Read the research: Shi, W., Zhang, Y. A., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2017). Ripple effects of CEO awards: Investigating the acquisition activities of superstar CEOs’ competitors. Strategic Management Journal, 38(10), 2080-2102.

Yan Anthea Zhang is Fayez Sarofim Vanguard Chair Professor of Strategic Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Robert E. Hoskisson is the George R. Brown Professor of Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Nick Anderson is a Pultizer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

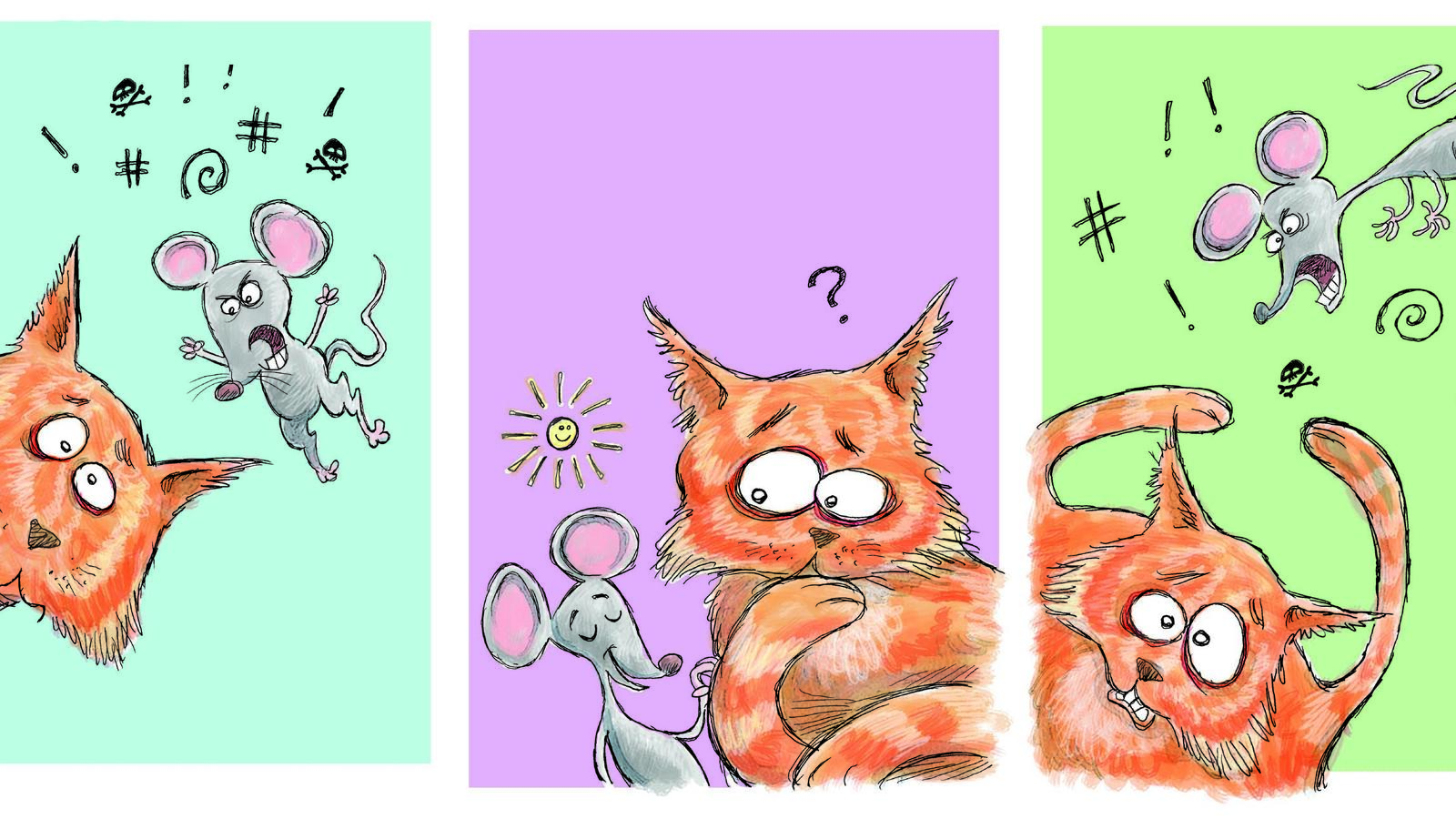

Cat And Mouse Game

Does erratic behavior work in deal-making?

Illustrated by Nick Anderson. Based on research by Hajo Adam (former Rice Business professor), Marwan Sinaceur, Gerben A. Van Kleef and Adam D. Galinsky.

Does Erratic Behavior Work In Deal-Making?

Want to know more about using anger in negotiations? Please see our other articles based on Hajo Adam's research Crazy Like A Fox and Mad About You.

To read the research: Sinaceur, M., Adam, H., Van Kleef, G. A., & Galinsky, A. D. (2013). The advantages of being unpredictable: How emotional inconsistency extracts concessions in negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 498-508.

Hajo Adam is a former assistant professor of management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Nick Anderson is a Pultizer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Give And Take

The best way to give when you’re not sure whom to trust.

By Jasmina Kelemen

What’s The Best Way To Give When You’re Not Sure Whom To Trust?

The disasters of the last year have been stunning: hurricanes, earthquakes, wildfires and, most recently, the Guatemalan volcano eruption that has engulfed whole villages, leaving a hundred dead and hundreds more missing.

Around the world, we feel driven to help — yet often stymied. At the same time the media has given unprecedented detail about humans in need, it has shed light on the limits of the institutions meant to help.

Where to give when even the Red Cross no longer inspires full confidence?

"More and more, donors are becoming concerned with how their donation is used," said Sara Nason, communications manager at the nonprofit Charity Navigator, which rates charities for transparency, efficiency and effectiveness.

These concerns are valid, added Juliet Sorensen, an associate dean at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law. "In the wake of a natural disaster, corruption and fraud abounds," she said. "In part it's because the emergency atmosphere does not lend itself to quality control or meaningful oversight."

In an international city such as Houston, residents are especially attuned to the needs of friends and family abroad — and the failures of institutions to come through. When Houston sank under Harvey's floodwaters last year, for example, the American Red Cross leapt into action with shelters and meals. Yet many donors couldn't forget the shadows looming over the nonprofit ever since its performance in post-earthquake Haiti, where more than a half-billion dollars in donations failed to rebuild even one rebuilt house in some stricken areas.

This week, in the wake of the catastrophe in Guatemala, potential donors have also grappled with their distrust of the country's institutions. "It is really sad, but we don't have trust in government institutions at this point. The day of the volcano eruption, the government actually had a press conference saying, 'We don't have any money for emergency situations,'" said Benito Juarez, a member of two community service associations of Guatemalan Americans. Juarez, who is the City of Houston's Manager for Immigrant and Refugee Affairs, said his compatriots' efforts to send aid in the past have been hamstrung by the government fees or barriers to distribution.

Echoing their experience, aid experts increasingly agree that in natural disasters like the volcano eruption, cash — the one resource most easily pilfered and diverted — is also what's most desperately needed.

So how should donors choose where to give?

First, nonprofit watchdogs say, don't be afraid to crunch the numbers. Use online tools that show how much a nonprofit spends on overhead and what percentage of the donations it receives goes to relief operations. One way to assess global nonprofit spending choices is Guidestar, which offers information about the mission, reputation, finances, programs and governance, among other things, of IRS-registered nonprofits. Another good source is Charity Navigator, which breaks down a nonprofit's financials and assigns a star rating that makes it easy to compare different organizations.

Second, consider supporting projects with lower risk. While corruption taints all economic sectors, some are especially vulnerable, notes economist Peter Rodriguez, dean of Rice Business. "Infrastructure projects are especially prone to corruption," he wrote in a recent paper on foreign corruption, "because they involve large investments and complex contracts in which corrupt payments can be easily be disguised."

And it might even make sense to give to trusted individuals. In those cases, advises Charity Navigator, look for groups with deep local ties, do your homework on the targeted charity and consider a long-term view of recovery needs.

J.J. Watt, the locally beloved defensive end for the Houston Texans, raised $37 million dollars for Harvey relief after starting with a humble appeal for $200,000. In Mexico, newly prominent fundraisers include actors Diego Luna and Gael García Bernal, who confronted distrust of government institutions by appealing for relief funds personally, vowing to publish how much they received, how the funds would be used and what the outcomes were of the efforts.

Similarly, in Houston, Juarez said that he and his friends are donating to a specific gofundme.com site whose Guatemala contact they know personally.

Whatever your choice, though, keep tabs on your nonprofit — and the news around the disaster —after you donate, experts agree. For many survivors, including those in Guatemala and Puerto Rico and Houston, rebuilding is a long and even more grueling process than escaping. Staying vigilant is also the best way to protect the investment you made for fellow humans in need. Keeping that link to the nonprofit you've supported, said Nason, "is crucial to ensuring that you trust the organization and know where your donation is being used."

Gold Standard: A sampling of institutions with high ratings from the watchdogs.

Guatemala

The veteran news agency PBS offers a concise outline of the volcano's ravages and has curated a vetted list of recommended Guatemala recovery charities.

A relative newcomer to disaster relief, gofundme has won trust from donors uncomfortable with government and other traditional institutions. Though no charity option is foolproof, gofundme offers a guarantee and a protocol for making sure your money reaches the correct hands.

United States

Habitat for Humanity: Builds and restores homes for lower-income communities and has a four-star rating, the highest possible, from Charity Navigator. In the wake of Harvey, it has committed to fully rebuilding 176 homes by December 31 in Houston’s hardest hit neighborhoods.

Community Foundation Sonoma County: A philanthropic organization supporting nonprofits in Sonoma County since 1983, it has started a Resilience Fund to support reconstruction after the recent wildfires. It has received 92 out of 100 possible points from Charity Navigator.

Mexico

Los Topos: Founded after the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, Los Topos is a volunteer rescue brigade that has assisted in earthquakes from Mexico to Nepal. The unpaid force uses funds to keep volunteers regularly trained and at the ready to assist at the next disaster. Donations can be made through Paypal at donativos@brigada-rescate-topos.org.

Fondo Unido Mexico: Part of the United Way network inside of Mexico, it focuses on rebuilding schools and community centers and training a culture that’s prepared to react to emergencies. It not only responds to the most visible natural disasters, but since 2011 has attended to less publicized emergencies caused by tropical storms and earthquakes in less populated regions.

Puerto Rico

Direct Relief: A humanitarian aid organization that gets a perfect, four-star rating from Charity Navigator for accountability and transparency. According to its website, 99.4 percent of its expenses are spent on programs and services. Its efforts in Puerto Rico focus on supporting community health centers and primary care associations.

Unidos Por Puerto Rico: A nonprofit spearheaded by the First Lady of Puerto Rico that grew out of a telethon to raise money for hurricane victims. Its board of directors consists of members from the private sector, representing some of the largest corporations on the island, who are tasked with making sure the funds are directed towards hurricane relief. It has enlisted outside, private auditors such as Deloitte and KPMG to track the funds and provides a breakdown on its website of all the goods it has delivered.

Jasmina Kelemen is a journalist who divides her time between Houston and Caracas, Venezuela. A former editor for Bloomberg News, she has reported from 4 continents and contributes to Houstonia magazine and Rice Business Wisdom.

This article also appeared in Gray Matters as "How do you know where your donations go in disasters?"

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Rite Of Passage

Being “between jobs” can mean being in a wasteland, or a place of growth.

Based on research by Otilia Obodaru (former Rice Business professor) and Herminia Ibarra

Being “Between Jobs” Can Mean Being In A Wasteland, Or A Place Of Growth

- As careers become less predictable, it’s more common than ever for people to find themselves in limbo between jobs.

- These periods of transition can induce fear, depression and self-doubt. But they also offer opportunities for creative growth.

- Viewing periods of limbo as opportunities to better understand ourselves and our options may help make them less painful.

To really learn who you are, get lost — “lost enough to find oneself,” as Robert Frost wrote. Social scientists agree. It may be painful, but fumbling through the chaos of uncertain times can inspire personal growth and ultimately improve performance — hopeful news at a time when no job is completely secure.

Social scientists refer to the periods of transition between jobs or social roles as liminal experiences, from “limina,” the Latin word for threshold. The concept of liminality is typically associated with anthropological research into rites of passage, but the term has also been used in sociology, psychology and even marketing.

Now, former Rice Business professor Otilia Obodaru and Herminia Ibarra of London Business School argue in a paper that the concept of liminality should be updated to apply to the 21st-century workplace. It is, they say, an apt description of the modern experience of living through career transitions.

Traditional liminal experiences centered on ritualized transitions from one social role to another — from childhood to adulthood, for example. Those transitions had the benefit of specific timelines, clear rules and institutionalized support in the form of guidance from elders. Perhaps most importantly, it was understood that after a period of trial one would emerge triumphantly on the next rung of the social order.

So nice, so comforting, and so not the case today for those who get laid off after years of loyalty and have no clue what’s coming next.

Liminality, Obodaru and Ibarra write, can feel much more precarious in our world of “jobless growth.” Without choosing to, many adults find themselves in career limbo — with no guarantee that they’ll advance to a higher rung. Lacking the built-in guidance of elders or a script for how to proceed, people in modern liminal phases often feel that the narrative thread of their lives has simply been left dangling.

Of course, some people don’t mind the uncertainty of being between jobs — or hovering between the dependence of adolescence and the independence of adulthood. As Obodaru and Ibarra note, for a subset of unemployed or underemployed Millennials who still live with their parents — dubbed “twixters” — this transitional period is more likely a choice, and it can go on indefinitely. The phenomenon, the professors write, “has been diagnosed as permanent liminality.”

But most people have a deeply ambivalent response to career uncertainty: it’s simultaneously anxiety-inducing and exciting, disorienting and liberating, frightening and exhilarating. And it is precisely from that ambivalence, if managed correctly, that personal growth can stem, Obodaru and Ibarra say.

The key to growing from uncertainty is, paradoxically, not bringing this uncomfortable period of transition to a premature end. “Tolerating painful discrepancies and allowing time for self-exploration and self-testing” are crucial to expanding your sense of purpose and identity, the professors write.

Whether it’s in the workplace or at home, this new model of transition can provide modern limbo-dwellers some comfort — and even guidance.

Life is changing. It can be tough to face an unknown future. But in the early 21st century, such uncertainty is also normal. In the absence of guides and rituals, it may help to know that modern limbo is a place where we all land at some point, and that it’s worth sticking around there for a while to learn what you can before scrambling out.

Otilia Obodaru is a former assistant professor of management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Ibarra, H., & Obodaru, O. (2016). Betwixt and between identities: Liminal experience in contemporary careers. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 47-64.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Rain Man

An interview with Eric Berger, Houston-based meteorologist and local hero.

By Weezie Mackey

An Interview With Eric Berger, Houston-Based Meteorologist And Local Hero

Rice University sent its first email about Tropical Storm Harvey midday on Thursday, August 24. By 6:25 that night, the storm upgraded to a hurricane, and Rice announced early closing for the following day. With safety as the highest priority, the business school cancelled Friday afternoon and evening classes and all Saturday events and classes. No one expected the weather to unfurl as it did over the next few days.

No one, except Eric Berger.

"I’d love nothing more than to write a post expressing some optimism about the rainfall forecast ahead, but as of now it looks really quite grim."

"Now is the time to get off the roads, get to your residence, and wait out a potentially long night of flooding."

9:14 pm Saturday, 8/26/17

"Houston is on the cusp of a major, widespread flood event that could affect thousands of homes."

10:53 pm Saturday, 8/26/17

"A bad situation has turned worse."

12:40 am Sunday, 8/27/17

You may have heard of Eric Berger if you live in Houston or you read Wired or you caught his interview with Elon Musk just before the Falcon Heavy rocket launch. He’s a certified meteorologist and senior space editor at Ars Technica, a website covering news and opinions in technology, science, politics and society. Before that, he was a Pulitzer Prize finalist at the Houston Chronicle for his coverage of Hurricane Ike, and before that he was the SciGuy blogger writing about nanometers and parsecs (a unit of distance in astronomy, by the way). Berger covers everything “from astronomy to private space to wonky NASA policy” to the Tesla CEO and his designer jeans. Mostly, he untangles the language of science and medicine for the general public. And the general public is loving it.

In October 2015 Berger founded the website Space City Weather to “cover Houston weather news and forecasting with accuracy and without hype.” Since Hurricane Harvey, Berger and the site’s managing editor Matt Lanza have become household names and unexpected heroes in Houston. Before, during and after the storm their clear, calm updates were posted several times a day.

Most comforting was the sense that they were in the eye of the storm with you.

"For the first time ever, the National Weather Service just issued what it is calling a “Flash Flood Emergency for Catastrophic Life Threatening Flooding.” And not to sound too flippant, but that sounds really bad. You should probably heed their advice — WHICH IS SIMPLY DO NOT TRAVEL. DO NOT IMPEDE WATER RESCUES IN PROGRESS.

Is that clear enough?

My wife, bless her, just asked me if Band 3 was it for the night. I wanted nothing more than to fall in her arms and tell her yes, this was it. By God, yes. Let’s go to bed and forget this ever happened. It had to be it, surely."

2 am Sunday, 8/27/17

One week he’s covering the eclipse for Ars Technica, the next he’s got the biggest storm to ever hit Houston. Daily website traffic tripled along with speaking engagements since then. When asked why people are obsessed with weather, Berger’s quick to answer, “They’re not obsessed with weather until it makes a difference in their lives.”

During Hurricane Harvey, it’s safe to say, weather made a difference in a lot of lives. Berger and Lanza’s voices became a safe harbor during the storm. People who had never heard of Berger or Space City Weather before were impatiently awaiting the next post, more than 60 in all, some only a few hours apart at the height of the storm. On Sunday, August 27, they posted nine times, twice in the middle of the night.

Below is an edited interview with Eric Berger.

RBW: Why is “no hype” a tagline of Space City Weather? Why is that important?

EB: It was something I started doing. Writing weather reports without any nonsense. There’s an audience for the other stuff too. I’ve been doing this since Katrina and Rita, it’s evolved from recognizing that need and style that fits with my personality. In Houston, it’s boring most of the year, until there’s a storm. People are obsessed during extreme weather. TV people have known this for a long time. And the internet has allowed people to get even more obsessed. Our coverage is the alternative to the craziness.

RBW: How much has Space City Weather grown since Harvey?

EB: Daily traffic has about tripled. Maybe 12,000 page views on a slow day. Originally, it was a struggle to figure out how to build it, monetize it at all, create an LLC, taxes. But the growth is all word of mouth. Honest to god, people sharing the site, Facebook, Twitter, Reddit. On Facebook there are 20,000 to 100,000 followers by just organic sharing.

RBW: What is it like to be a celebrity?

EB: My kids are 10 and 14. They give me a hard time. It’s nice to have people thank me. They appreciate the site. It happened after Ike. My picture was on the front page of the paper — sciguy hurricane coverage. Blog. Livechats. The intense hunger for information was eye opening. It wasn’t celebrity; it was recognition.

RBW: Would you say you have a personal brand?

EB: No-hype guy. I’d been pushing the Chronicle to create a weather site. There’s an opening in Houston. TV was covered. Internet was a revelation to weather communication. I built it around this idea of no hype. That was really rewarding. I met Matt in 2014 and brought him in to help out. We share a similar philosophy, and he picked up on the vibe immediately. When I left the paper, I turned to him and asked, “Do you want to be a part of this?”

RBW: Tell us about your fundrasing campaign?

EB: We have two ways to build up support to pay for server expenses. One is an annual fundraiser where we sell a t-shirt. There was a tremendous response this year. And then we stopped doing ads on the site in May 2016, so we tried to find a monthly sponsor. Reliant came on board for the second half of this year. I like that because I don’t have to deal with the hassle. When there’s weather, you’ve got to be there. A lot of people gave me advice after Harvey. But as long as I’m getting a decent amount of compensation for the time, I'm fine with that.

RBW: Are there words responsible weather casters avoid?

EB: Until Friday [August 25, 2017], I would avoid comparing any storm as the next Tropical Storm Allison. Because Allison was extreme flooding. I would consciously not use it. The word now is Harvey.

Since Eric Berger visited Rice Business, his star continues to rise. Read more about him in in Wired's article “Meet the Unlikely Hero Who Predicted Hurricane Harvey’s Floods"

Eric Berger has an astronomy degree from the University of Texas and a master’s in journalism from the University of Missouri. He previously worked at the Houston Chronicle for 17 years, where the paper was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2009 for his coverage of Hurricane Ike.

Weezie Mackey is the Associate Director of Marketing and Communications at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story