Boiler Room

What you absolutely need to know about microcap stock scams.

Based on research by Brian Rountree, Karen Nelson and Richard Price

What You Absolutely Need To Know About Microcap Stock Scams

- “Pump and dump” scams lure potential investors to a stock with fake news. When the investor buys at an artificially inflated price, the scam artists then sell.

- The more effective scams bundle unrealistic stock projections with seemingly credible information, including a company press release.

- Though these scams constitute fraud, the chances of an SEC investigation decrease when the spams involve a press release.

It’s called “pump and dump,” and it’s fraud. Con artists lure potential investors by deluging them with fake online news to get them to buy a particular stock. When the marks start buying at what amounts to an artificially inflated price, the scam artists sell, leaving the dupes with micro-cap stocks or cryptocurrencies whose value has collapsed.

Earlier this decade, Rice Business professor Brian Rountree joined then-Rice Business professors Karen Nelson, now at Texas Christian University, and Richard Price, now at the University of Oklahoma, in probing this type of fraud and the investors who fall for it. While the schemes vary, the researchers found that they work best when the fake news is bundled with seemingly reputable information issued by the company itself. Wildly optimistic stock price projections seem much more plausible when accompanied by a company press release.

In several respects, such cons offer a natural setting to examine what gets the attention of unsophisticated investors. To better understand this dynamic, Rountree’s team analyzed 639 unique spam events from internet archives of spam messages between January 1999 and May 2006.

Sophisticated pump and dumps generally work on two levels. First, there is the internet equivalent of boiler room con artists, people who buy a micro-cap stock, spam fake news about its prospects, then reap the rewards.

To make any kind of return on their scam, though, these grifters have to actually buy the stock in massive quantities, exposing themselves to significant risk of investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission. They’re further hindered by a lack of access to corporate information. Hence, these kinds of spammers will more often than not generate flattering material about a stock, but aren’t likely to include corporate press release information.

The second type of scammers have some kind of relationship with corporate management. They already hold or receive shares as compensation, allowing them to profit from a rise in liquidity even if the stock price does not rise much.

In this scenario, company executives may be participants in the scam. These schemes are similar to paid advertising, to raise awareness about a company’s stock. Nevertheless, the odds of the overly optimistic projections actually coming true are equivalent to the odds of picking winning lottery numbers.

But since these messages include full disclosure of a relationship with a company, and the analysis is accompanied by caveats indicating there is no guarantee of a return, the SEC has a difficult time prosecuting such cases.

Both types of con artist usually favor attention-grabbing micro-cap stocks (those in the news and with high past returns) with relatively low transaction costs. But, the researchers found, when potential investors got spam messages conveying vague puffery attached to nothing that might be considered factual, they were less likely to buy. The lack of anything official-looking inspired at least a minimum level of discernment.

Investors were far more vulnerable to the second type of scam. When spam messages also contained actual press release information, buying increased significantly — even if the press release information was old. The presence of a press release gave the spam message an official tone that induced more people to at least consider the message, which in turn translated to more investors actually buying the stock.

Since pump and dump scams are fraud, they are a crime to be investigated by the SEC. But the researchers discovered a troubling corollary to their findings: The SEC is less likely to investigate schemes that involve press release information and the inclusion of a disclaimer, which are exactly the schemes most likely to attract investor attention.

So buyer beware. The more professional-looking the offer of free money, the more professional the scam itself.

Brian Rountree is an associate professor of accounting at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Nelson, K. K., Price, R. A. & Rountree, B. R. (2013). Are individual investors influenced by the optimism and credibility of stock spam recommendations? Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 40(9-10), 1155–1183.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Story Time

Why the stories companies tell themselves are serious business.

Based on research by Scott Sonenshein, Eero Vaara and David Boje

Why The Stories Companies Tell Themselves Are Serious Business

- Companies, like people, give themselves narratives that provide them with meaning.

- Every company exists within a web of narratives, which are often contradictory.

- Narratives provide both individuals and companies what they need to compete, to accept failure and to grow.

A string of workers gets hurt on the job at a major energy firm. Though the company insists it’s dedicated to improving safety, many employees believe that it’s all talk and no action. Meanwhile, management is convinced that morale has never been better. It’s a tug-of-reality, and such simultaneous, contradictory narratives could apply to any number of big firms around the world.

The urge to tell stories that justify our attitudes and behavior is part of what it means to be human. Big companies are agglomerations of humans, so they become a kind of universe of narratives. And like individuals, companies make sense of their behavior by using mere fragments of stories.

In a recent literature survey, Rice Business professor Scott Sonenshein and colleagues Eero Vaara of Aalto University School of Business and David Boje of New Mexico State University looked closely at the ways corporations tell and perpetuate their stories. Analyzing a series of company narratives as a literary critic might study a novel, Sonenshein’s team noted that different companies, like individuals, explain their behavior with distinct narratives. Often, these narratives bang up against each other.

Such contradictions can be a form of warfare, with high stakes attached. Imagine two companies at loggerheads, with one attempting a hostile takeover of the other. Naturally, the aggressor firm will spin a story about why the takeover will be good for the market, the firm and probably society at large. The target firm will likely cry foul, protesting that the move saps the economic and even cultural well-being of its workers, stakeholders and consumers in general.

This plurality of narratives can also exist within the universe of a single firm. In fact, an individual employee may authentically believe different storylines about the same workplace, depending on whom he or she is talking to. The nature of office politics guarantees different storylines for different audiences. These narratives can often be complex and ambiguous.

In one experiment cited by Sonenshein and his colleagues, managers were told to write a note to themselves about the usefulness of a company product. They were then told to write an email to a superior about the same product. The result: Managers typically used moral language when writing about the product to themselves, and economic language when writing about the product to their superior.

Similarly, entrepreneurs often use an array of narratives to explain their success or failure. Sonenshein groups these narratives into general types familiar from myths and literature. In each type, the story hinges on something different. There’s “catharsis,” where the story hinges on one person’s responsibility or revelation; in “hubris,” it’s venture-wide responsibility; “zeitgeist,” industry-wide responsibility; “betrayal,” one responsible agent inside the venture; “nemesis,” a responsible external agent; “mechanistic,” an uncontrollable non-human element within the venture; and, simply, “fate.”

These stories, Sonenshein notes, are more than just excuses. They’re mechanisms that help entrepreneurs cope with events.

At the same time, when there’s a crisis, some groups within an institution form narratives that blame others for corporate shortcomings. Organizational change unfolds with multiple narratives offered by different parties, each with their own agenda.

For companies and individuals alike, narratives can provide a way to deal with setbacks and trauma. That’s because stories allow us to understand our identities even as they shift. In today’s fluid employment environment, the stories we tell ourselves can mean the difference between moving forward and giving up altogether.

There is still much that remains to be understood about how storytelling shapes organizational narratives. While corporate origin stories can influence the lives of individual workers, an individual’s story can also powerfully impact an organization. The narrative of Steve Jobs, for example, shaped the vision of Apple as a company.

Similarly, companies need to better understand the voices that resist an accepted storyline. A 2013 Twitter Q&A by J.P. Morgan turned into a public relations meltdown when a discussion on the firm’s career opportunities launched a backlash of more than 18,000 comments from Twitter users still angry about the 2008 recession. One writer demanded, “Does the sleaze wash off with a regular shower, or do you have to use something special like babies tears? #AskJPM.”

These counter narratives can be irksome. But listening to them can form the basis for essential change.

Counter narratives also abound within firms. At Microsoft, for example, more than 100 employees recently protested the company’s work with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), arguing that the agency’s policy of incarcerating child immigrants was immoral.

Between the current political polarization, and the many ways dissident voices can be heard via social media, companies will find it harder than ever to silence unofficial narratives. Sonenshein offers an alternative: Rather than stamping them out, follow these alternative storylines carefully, and embrace them as possible roadmaps to success.

Scott Sonenshein is the Henry Gardiner Symonds Professor of Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Vaara, E., Sonenshein, S. & Boje, D. (2017). Narratives as sources of stability and change in organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 495-560.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Quiet Riot

How can introverts make noise without raising their voices?

By Tracy L. Barnett

How Can Introverts Make Noise Without Raising Their Voices?

The morning after the 2016 election, Sophia Dembling woke up feeling shocked, appalled and terrified at what lay ahead. “And I still am,” she confessed.

She’d been planning to attend Hillary Clinton’s inauguration, so as she stewed over the headlines, one jumped out at her. She decided to go to Washington, D.C., anyway — and join the Women’s March. But marching, and bunking with 11 strangers, was not an appealing prospect.

Dembling, author of “The Introvert's Way: Living a Quiet Life in a Noisy World,” is an introvert. She’d never ventured into political activism, but thought the stakes were so high that she needed to get involved. The decision has provided endless fodder for The Introvert’s Corner, her blog on Psychology Today.

This election cycle, a growing number of organizers are working to increase civic engagement among the long-overlooked one-third to one-half of the population who identify as introverted. In part, this shift is due to an explosion in technologies that provide less intrusive ways to participate. In part it’s due to rising awareness of the needs of this quiet, but sizeable, minority.

For many, the epiphany was unleashed with Susan Cain’s 2012 book “Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking.” Cain’s book argues that Western civilization has exalted an extroverted ideal, undervaluing and underutilizing the skills of introverts.

“The thing about extroverts is that they are loud and proud, so we are more likely to hear what they are doing than we are to hear about introverts' contributions,” said Dembling. “So it can be easy to imagine that only extroverts need apply. But this is not the case. All of our skills and contributions matter.”

While extroverts are energized by social stimulation and contact, introverts find it draining. That means they’re often alienated by traditional types of activism: door-knocking, cold-calling, marching with bullhorns and the like.

“Introverts are by no means apolitical, they just find the world a little more difficult to navigate,” said Rice University political science professor Robert Stein. A University of Nebraska study found that even the act of voting in a traditional voting booth raises cortisone levels — a physiological indicator of stress. The study showed that people who voted at home had significantly lower cortisone levels. Those findings underscore the need to make absentee ballots universally available, Stein said — and they apply to political participation as well.

“If you’re an introvert and you don’t want to go out and march in the streets, or go to a political rally, it doesn’t mean you lack efficacy. You can still vote, you can still express your opinion in Facebook posts, on blogs, in newspaper articles; you can make campaign contributions,” he said.

Kerryn Rodriguez, a Cleveland, Texas, schoolteacher, tried to do traditional activism but found the stress levels impossible to navigate. First it was calls to a phone bank; then it was door-to-door canvassing. “Just the idea of going up to someone’s door had my heart racing a little bit, and my palms sweating,” she says.

Fortunately for people like Rodriguez, introverts and their needs are now on organizers’ radar, and there are more ways than ever for them to get involved.

“There are there are platforms that allow you to do text canvassing, and there are programs that allow you to do call scripts,” said Brandon Naylor of Democracy Works, a nonpartisan group promoting its “TurboVote Challenge” to reach the lofty goal of 80 percent voter turnout by 2024. “There are a bunch of different ways these days that introverts can be involved.”

Texting as a tool for voter outreach is just one way to mobilize a growing army of introverted volunteers. Texting came of age during the 2016 presidential campaign and has gained ground with the 2018 midterms.

To Gerrit Lansing, it’s just a sign of the times. “In general, I think politics is moving from a service-based industry to a technology-based industry,” said Lansing, a former chief digital officer for the Republican National Committee and the White House, and co-founder of Opn Sesame, a texting app used by Republican campaigns. “While I’ll be honest, I don’t think we built these tools with introverts in mind, the fact that it’s a positive outcome is great. You can bring more people into participating in managing the republic, and having a good election.”

Resistance Labs, a texting platform used more by Democrats, employs a third-party app called Hustle so that volunteers can text from their own phones without revealing their phone numbers.

“For someone who’s introverted, it’s wonderful,” says Jacinth Sohi, the platform’s operations manager. “When someone replies, you have that layer of the phone. People who are more analytical want time to process and think through a more thoughtful response.”

But texting works on many levels, and not just for introverts, says Sohil, who identifies not as an introvert, but as a millennial.

“It’s generational, too. I think that younger folks, we’re not used to calling on the phone. I seem very much like an extrovert, but I’ll avoid cold-calling somebody at all possible costs,” she says. Text messaging also gives the messenger the advantage of time. “People who are more analytical want time to process and think through what their answer will be, and you don’t have that luxury with a live phone call.”

But there are much older technologies that are mobilizing introverted activists, as well. One is postcarding; another is sewing.

Tony McMullin was phone-banking as a volunteer for a congressional campaign in Georgia when he started seeing Facebook posts from friends in other parts of the country who were frustrated at not being able to help out with the campaign. He hit on the idea to share his list and his talking points with his friends and ask them to send postcards to the voters. Eighteen months and 3 million addresses later, his Postcards to Voters project has engaged more than 40,000 volunteers in campaigns all across the country.

“It’s not a new thing; in fact, it’s a very old approach, but it’s sort of lost its place with all the technology,” said McMullin. “This is activism for introverts. They really can’t bring themselves to get on the phone and talk to strangers — they cannot go door to door, they just feel horrible doing it.”

But postcarding, like texting, appeals to a wide range of people for a host of reasons, says McMullin. People with mobility issues, or foreign accents — and in some places, people of color — can find it difficult to go door-to-door. This gives them another option.

Another door has opened with the advent of craftivism, a concept popularized by, among others, British author Sarah Corbett, founder of the global Craftivist Collective.

As a professional activist, Corbett worked for nonprofits on issues ranging from maternal health to fair wages to climate change. She is passionate about the work, but found that it left her drained and exhausted, no matter how much she believed in the cause. She never understood why until she encountered Cain’s writing on introverts. “The more I read, the more I realized I wasn’t a freak — and that I had a different skillset that was just as valid.”

Corbett’s breakthrough led to a shift in her career that has resonated internationally as she began tailoring her work to introverts — and to extroverts who long for a kinder, quieter, more creative approach to activism that has proven to be highly effective.

Her campaigns began to take a different shape. She discovered sewing on a train trip, where she wanted to do something creative but couldn’t paint — and then hit upon an idea. She ended up creating a campaign in which activists created gift handkerchiefs with embroidered messages for business and political leaders, ultimately leading to pay increases for 50,000 people. Other campaigns generated embroidered “mini-banners” to be hung at eye level in public places, and other messages were worn on a heart on one’s sleeve.

A fashion industry intervention involved “shopdropping” — essentially the opposite of shoplifting. Makers would drop tiny, hand-lettered scrolls into, for example, the pockets of clothing sold by retailers who engage in unfair trade practices, hoping customers would find and contemplate their questions about the clothing’s origins. The campaign resulted in global media on the homepage of BBC News, a double-page spread in the Guardian and coverage in fashion magazines because of Corbett’s “gentle protest” approach to activism.

Her experiences in organizing such campaigns led to her book, “How to be a Craftivist: The Art of Gentle Protest,” released earlier this year in the U.S. The idea, Corbett said, is to “strategically thread love, humility and beauty through their activism instead of hate, ugliness or aggression.”

“Craftivism can be a useful tool to encourage people to participate in two ways. First, you can use the process of crafting to channel your anger or fear into action,” she said. “Secondly you can use the handmade object itself as a catalyst for conversation, connection and action in others. It might sound naive but it’s far from it. I’m proud to say our craftivism has helped change hearts, minds, policies and laws.”

Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer based in Guadalajara.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep exploring

Paper Work

How can Mexico’s regulatory code strengthen its markets?

Based on research by Brian Rountree, Richard Price and Francisco J. Román.

How Can Mexico’s Regulatory Code Strengthen Its Markets?

- Because fair markets are central to a vibrant economy, in 1999 the Mexican government enacted regulations to bring more transparency to financial reporting.

- Despite the new regulations, companies remained largely inefficient.

- To revamp its capital markets, Mexico needs a slew of changes including commitment to enforcing financial regulations that protect minority shareholders.

Theoretically, at least, capital markets allow millions of investors to allocate resources in a way that maximizes competitiveness and efficiency. When these markets are fair, they play a central role in a vibrant economy and society. Transparent financial markets lure capital, allowing economies to pick up steam and grow more quickly. Without transparency, on the other hand, investors are more easily defrauded. Inequality spreads. A country’s economy can quickly decline.

In 1999, Mexico initiated a Code of Best Corporate Practices in order to ensure greater market efficiency and better corporate performance. The following year, roughly 28 percent of publicly traded firms complied with three-quarters or more of the criteria. By 2004, compliance jumped to 79 percent. One would think that this compliance with the new regulations would mean that corporate performance generally would increase.

But good intentions are one thing and reality another. After studying market behavior, Rice Business professor Brian Rountree, professor Richard Price at the University of Oklahoma and professor Francisco Roman at George Mason University found that compliance with the code had little, if any, effect on Mexican firms’ overall corporate performance. In fact, the regulations also showed little if any effect on overall earnings management or return on equity.

To reach these conclusions, the professors analyzed a sample that included all nonfinancial firms listed on the Mexican stock exchange as well as stock returns, financial statement data, and governance data over the period of 2000 to 2004. Governance data was collected from each company’s annual Code of ‘Best’ Corporate Practices questionnaire filed with Mexico’s regulator.

As a proxy for governance strength, the researchers devised a “governance score” based on the level of compliance with the code’s recommended provisions.

So what went wrong with the code? On paper, its mandates were exemplary. Company boards were supposed to include at least 25 percent independent directors, and firms were to limit their size to 20 directors and use audit committees led by independent directors. But while many provisions of this code are mandatory, there was little in the way of oversight by regulators. Company reports were simply not questioned.

The same held for investor protections. Firms from Mexico that were cross-listed in the United States often escaped enforcement of insider trading laws by the Securities and Exchange Commission. And as late as 2010, the Mexican judicial system’s commitment to minority shareholder protection was still untested, prompting significant questions about the perceived improvements in minority shareholder protection by stock market participants.

Regulations, in sum, are only as good as efforts to enforcement. And while insider trading laws have existed in Mexico since 1975, the first enforcement attempt didn’t occur until 2005. Even then, the action was spurred by the United States, without firm commitment from Mexican authorities.

And those companies that complied with the letter of the law still had to adopt costly measures to signal their investment worthiness to the market. These firms, the scholars found, had a higher propensity to pay dividends and give marginally greater dividend yields than did the lower-compliance firms that also paid dividends. In other words, to reduce agency concerns, the Mexican firms with higher governance scores resorted to the costly mechanism of paying dividends, because the market simply did not value compliance with the code.

The researchers theorize that the weak links they found between company performance and compliance could be related to the limited competition among Mexico’s public firms. Together, the concentrated ownership environment and weak legal system muffled the impact of the new regulatory code on Mexican capital markets. Market monitoring alone was just not enough to create fundamental economic changes.

The results suggest that Mexico’s efforts to boost transparency must be supplemented with stronger enforcement. It’s unclear, however, whether the conflict between insiders and minority outside shareholders can be overcome without major changes in the company ownership structures. While the groundbreaking 1999 code showed the will to improve market efficiency, the scholars warned, only enforcement and perhaps restructuring can pave the way.

Brian Rountree is an associate professor of accounting at the Jesse Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

For further reading please see: Price, R., Román, F. J., & Rountree, B. (2011). The impact of governance reform on performance and transparency. Journal of Financial Economics 99(1), 76–96.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Tweetstorm

What’s at the heart of campaign word storms?

By Wagner Kamakura

What’s At The Heart Of Campaign Word Storms?

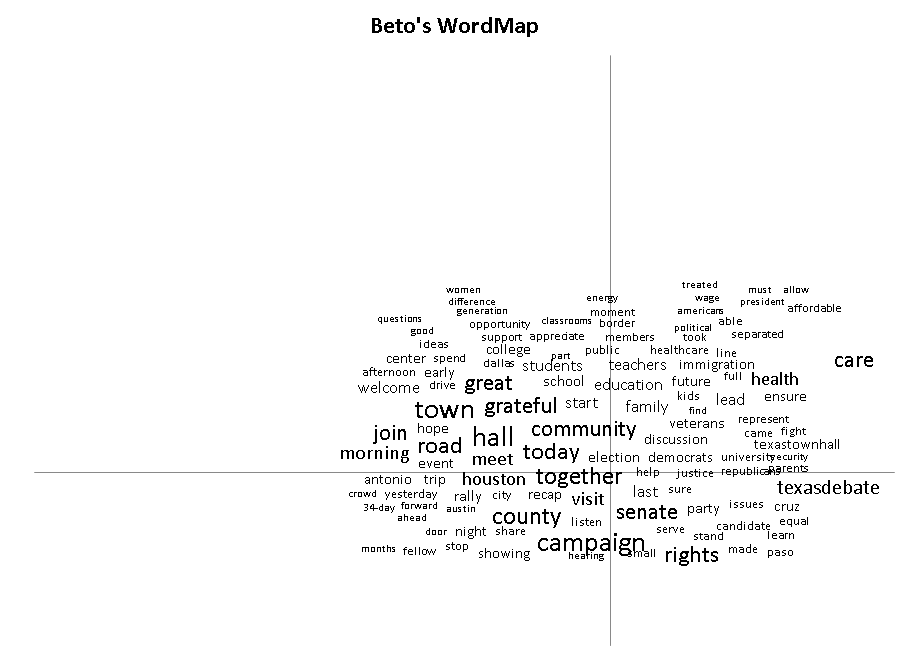

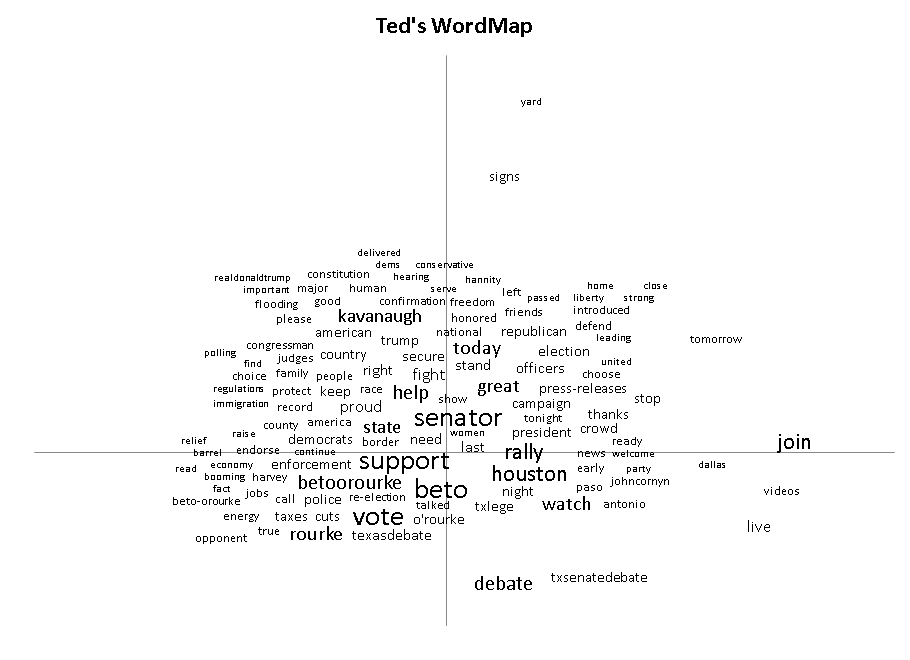

- Rice Business Professor Wagner Kamakura created a tool called WordMap, which he used to analyze tweets in the 2018 midterm elections.

- These images produced by WordMap are word clouds formed from the 500 longest tweets from U.S. Senate candidates Beto O’Rourke and Ted Cruz.

- WordMap can also be used to understand what consumers are saying about brands on social media.

Wagner Kamakura: The images above show word clouds formed from the 500 longest (more than 100 characters) tweets from competing U.S. Senate candidates Beto O’Rourke and Ted Cruz. I created the word clouds by some text-mining using my WordMap tool (you can view a YouTube tutorial video).

The tool produces a word cloud that reflects not only the frequency of the words used by the two candidates (as other word clouds do), but also how often they are used in the same tweet. In these images, frequency is represented by the font size, while affinity is represented by proximity of the words in the WordMap.

WordMap is one of the tools of KATE (Kamakura’s Analytic Tools for Excel), which I use in my Advanced Business Analytics course in the Rice Business EMBA program. WordMap can be used to understand what consumers are saying about your brand on social media, or to understand customer reviews. You can see a description of KATE here. I should note that WordMap tool is most useful for advanced users who are familiar with Excel add-ins. Its product, these candidate word clouds, like the candidates, speak for themselves.

Wagner Kamakura was the Jesse H. Jones Professor of Marketing at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Poll Vaulting

Innovators are finding new ways to encourage people to vote. Will it work?

By Tracy L. Barnett

Innovators Are Finding New Ways To Encourage People To Vote. Will It Work?

Austin event planner Natalie George has a talent for transformation. A pop-up clothing boutique she designed turned an abandoned strip mall into a hip showroom; a furniture store became a cozy dance venue for a cabaret series she concocted. Creating the buzzworthy is her business. Now, to her own surprise, she’s turned that talent toward getting out the vote.

“I never looked out and saw someone who looked like me — so I saw no reason to connect to politics,” George says. But as she watched the stakes rise on the political landscape, something shifted. When two of her friends, haunted by the family separation crisis on the border, approached George about doing a fundraiser, she said yes. Their idea evolved into The Show Up: a pop-up event that became an ongoing platform for energizing artistic types to vote.

George isn’t the only innovator urging more people to vote. From New York to San Diego, and from Memphis to Minnesota, activists are launching everything from flash mobs to food trucks to mobilize voters. Sites for get-out-the vote schemes range from beaches to music festivals, and in the case of a troupe of costumed superheroes, the annual San Diego Comic-Con.

Most famously, the formerly apolitical pop star Taylor Swift caused a furor — and a 370,000-person spike in voter registrations in 72 hours — with a single Instagram post urging her fans to register and vote.

But will these efforts make a difference? Earlier efforts to increase the vote have had only paltry success. Voter turnout in the U.S. trails that of most developed countries, even in presidential elections.

On the bright side, the turnout for early midterm voting this month has been astronomical: On the first day of early voting in Texas, turnout was up 325 percent in Dallas County and 213 percent in Harris County compared to 2014. Historically, however, turnout at midterms is up to 20 percent lower than in presidential years. The reasons are many, experts say: from the complexity of our country’s voting system to widespread disillusionment.

For one thing, the U.S. system is not really designed to facilitate participation, said Wagner Kamakura, a marketing professor at Rice Business. A two-round voting system such as the one used in his native Brazil, and on which he has done extensive research, can yield much higher voter participation, he noted.

“This two-round election system, the most common in the world for electing heads of state, is quite different from the crazy system we have in the U.S., where people are discouraged — or even blocked — from voting, and the actual winner is not the one with the most votes. I wouldn’t call it real ‘democracy,’” Kamakura said. “In Brazil, close to 73 percent of eligible voters cast their votes in the first round, which is a far cry from what we see in the U.S.”

Compare that to the 2012 and 2016 U.S. presidential elections, when voter participation was just a little over 61 percent. In the 2014 midterm election, voter turnout was a dismal 36.6 percent, the lowest since World War II.

Boosting those numbers has motivated a whole host of data geeks, designers, event planners, artists and others who have focused their creative energy on the challenge. Houston computer programmer Nile Dixon, for example, developed a chat bot to help people find the closest shelter during Hurricane Harvey; now he’s adapted it to help up to 20,000 Texas voters find their polling place.

Boston attorney and environmentalist Nathaniel Stinnett, wondering why the environment didn’t show up in more political discourse, discovered that environmentalists as a group have an extremely poor voting record. So he left his position to found the Environmental Voter Project, bringing on an army of interns to mobilize the environmental vote.

In St. Louis, picking up on the excitement generated in the African-American community by the blockbuster film “Black Panther,” activist Kayla Reed helped launch #WakandaTheVote. The project allowed people to set up voter registration events at local movie theaters or register to vote via text message. The success of that drive was followed with #WrinkleTheVote, aimed at parents, young adults, babysitters and teachers who took their children to see “A Wrinkle in Time.”

Sacramento journalist and poet Raquel Ruiz, meanwhile, was moved to tears and then to action by the immigration issue. Her arts group MAP California teamed up with Nagual Theater Inc. to produce “Letters from the Wall,” a work of street theater compiled from letters written by the families of immigrants who have lost loved ones. The idea is to raise awareness about immigration policy and motivate people to go to the polls. Ruiz, herself a Colombian immigrant, will be reading the letter of a mother who lost her son at the border while seeking asylum.

While much of the current activity is designed to increase voter turnout in this year’s election, there are also initiatives designed to improve turnout in the years to come.

Adam Eichen, co-author of the book Daring Democracy: Igniting Power, Meaning, and Connection for the America We Want, points to a number of ways to build voter turnout, beginning with how we register voters. “Our voter registration system is antiquated and deters voting,” Eichen said. “We’re in the 21st century; election officials don’t need multiple weeks to process a registration form. Voters, many of whom have busy lives, should be able to register to vote on Election Day.”

One reform that could bring on an estimated 50 million new potential voters in one fell swoop: automatic voter registration. Under this system, eligible citizens who interact with government agencies — for example, when they get their driver’s license – are automatically registered to vote unless they choose to decline. Since Oregon adopted this approach in 2016, its voter registration has quadrupled; 12 other states and the District of Columbia have followed suit.

Making Election Day a national holiday is another idea we could import from other countries. In the last midterms, some 35 percent of those who didn’t vote said scheduling conflicts with work or school kept them from the polls. Vote.org has launched ElectionDay.org to encourage companies to give their employees Election Day off, and more than 250 have signed on. One of those, New York-based Blue Point Brewery, has launched a Voters’ Day Off beer, complete with petition on the side of the can that consumers can sign and mail to the Senate, advocating a national holiday.

Allowing voters to participate through innovative “Democracy Voucher” public financing programs like the one in Seattle could foster engagement, as well, said Eichen. There every voter is given four $25 vouchers to donate to the candidate of their choice. “Beyond democratizing political financing, the program encourages residents to research candidates and decide whom they want to financially support,” he said. “This should lead to more of an affinity for the political process, while also expanding who has a voice. In Seattle, one candidate even reportedly collected donations from the homeless population.”

What impact all of this might have, of course, won’t be clear until after Nov. 6. But there are already indications that for this year, at least, the push to get people to the polls is working. A surge in voter turnout for the spring midterm primary was one indicator. And a poll from Tufts University showed high levels of young people, usually the least likely to vote, paying attention and planning to vote.

By the second day of Texas’ early midterm voting this month, the in-person vote and mail-in ballots in six counties had already exceeded the total early voting in 2016’s presidential election. Nearly 20 percent of those first day ballots were cast by non-primary voters, while between 5 and 9 percent appeared to be first-time voters. It may not yet be the crashing wave that get-out-the-vote innovators hope for. But it’s clearly a rising swell.

Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer based in Guadalajara.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Hunger Games

How snacking and spending reflect beliefs about inequality.

Based on research by Vikas Mittal, Yinlong Zhang and Karen Page Winterich

How Snacking And Spending Reflect Beliefs About Inequality

- “Power distance belief” is the degree of power disparity that people expect and accept in their culture.

- Power distance belief and compulsive spending are inversely related.

- The less people accept that there is inequality in power, the more likely they are to buy vice products such as junk food.

Power imbalance in our society is a fact of life. Get over it.

If you disagree with this statement, you may also prefer Ben and Jerry’s ice cream over a handful of almonds after dinner. You may even be more likely to be an impulsive shopper.

Improbable as this may sound, a study by Rice Business professor Vikas Mittal and colleagues Yinlong Zhang of the University of Texas at San Antonio and Karen Page Winterich of Pennsylvania State University shows there is a link between our beliefs about social equality and our buying habits. In six different studies that included surveys and experiments with more than 15,000 urban households in in the U.S. and 14 different Asian and Asia-Pacific countries including China, New Zealand, Japan and India, Mittal and his colleagues examined the link between a country’s level of “power distance belief” and shopping habits.

Power distance belief is the extent to which an person sees social inequality as inevitable. It’s a subtle mindset, not predictable by factors such as political ideology, country GDP or nationality.

Instead, it’s revealed by “yes” answers to survey questions like these: “As citizens we should put high value on conformity.” “I would like to work with a manager who expects subordinates

to carry out decisions loyally and without raising questions.” “In work-related matters, managers have a right to expect obedience from their subordinates.” While power distance belief is an individual trait, past researchers have also measured its levels in various countries.

People who tend to accept power disparity, Mittal and his fellow researchers found, work harder to control their impulses during shopping. Those who don’t believe inequality is the rule tend to fill their carts with junk food.

To be sure, Mittal and his team write, there’s a big difference between impulsive buying and shopping that is simply unplanned. Impulsive buying tends to be haphazard, a behavior of consumers who just can’t seem to control themselves.

What’s the connection? In countries where people refuse to accept power imbalance as a norm, Mittal says, people speak out much more. Students from such cultures are encouraged to express their differences publicly and disagree with their teachers if necessary. In other words, they’re encouraged to exhibit less restraint. Over time, people in such countries tend to place a higher emphasis on immediate gratification as opposed to restraint, the researchers found.

But does it follow that choosing donuts over egg whites for breakfast reflects one’s beliefs about power? Mittal and his fellow researchers demonstrate that it does.

One study, involving 170 undergraduates from a large U.S. university, illustrated such choices in action. First, the students were screened to judge their beliefs about power imbalance. Next, each was given a task assessing their willingness to spend money on junk food.

Imagine you had $10 in cash, each student was told. Now, choose from a list of items that includes both “vice products” — a Snickers bar, potato chips and cola — and “virtue products” — a granola bar, an apple and orange juice. Students who rejected power disparity were more likely to crave the Snickers and Coke.

The ability to act with self-restraint, Mittal and his team theorize, is linked to how we understand inequality. Individuals who accept power imbalance as a fact of life are more conditioned to show self-control. In turn, this helps develop a kind of mental muscle memory to control different urges — including the urge to spend whimsically.

Critically, the researchers found, these choices have little to do with an individual’s innate character. Instead, acceptance of power disparities could actually be prompted in labs, where messages designed to prompt acceptance of power inequality actually led to less consumption of vice products.

From a business perspective, the research could be groundbreaking for firms in multicultural markets. Studying cultural beliefs about inequality could yield key advertising strategies, based on whether members of a particular market see their product as a virtue or a vice.

Mittal’s research also presents implications for more than selling ice cream and chips. Whether we reach for a Snickers bar or a handful of almonds, it’s worth examining how these traits correlate to our internal views of power. Do we live in an equitable society? Can it ever be made so? How would we eat, buy, and spend if the world looked like it could change?

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing and Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Zhang, Y., Winterich, K. P. & Mittal, V. (2010). Power distance belief and impulsive buying. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(5), 945-954.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Fuel Spill

Will oil prices divert outrage over a political murder?

By William M. Arnold and Jim Krane

Will Oil Prices Divert Outrage Over A Journalist's Murder?

This article originally appeared in POLITICO Magazine as "Is Saudi Arabia Helping Trump in the Midterms?"

The three-way test of wills over Saudi Arabia’s murder of an exiled journalist has started to play out in oil markets.

Each day, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan maintains his drip feed of grisly details of Jamal Khashoggi’s killing in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul. Each day, a reluctant President Donald Trump is forced to respond to a new revelation. The affair has betrayed a yet unseen presidential aptitude for restraint.

Meanwhile, the Saudis’ initially combative tone has been quietly replaced with a more deferential stance. They have opened the valves on their idled oil production, exactly as Trump has demanded in his tweets. Saudi oil minister Khalid al-Falih has talked down oil prices with unusually forthright public statements, saying the kingdom will make sure global demand is met, no matter what.

For Trump and his embattled Republican allies in the U.S. midterm elections, the change in Saudi behavior is welcome. And as long as Trump soft-pedals the Khashoggi affair, it seems the Saudis are willing to cooperate with the American president’s oil market wishes.

A few weeks ago, there were rumors that Trump was pondering an election-timed release from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Now, with the Saudis on board, U.S. gasoline prices — the third rail of domestic politics — should remain low at election time.

If Trump’s measured responses are incentivizing Saudi production increases, the president’s policies are working. The international oil price is down about $9, from $85 just after Khashoggi’s murder to $76 on Tuesday.

Prior to the Khashoggi murder, Saudi Arabia had been slow-walking promised production increases despite strong evidence that Trump’s sanctions on Iran were strangling oil markets. Saudi oil output rose by just 300,000 barrels per day between June and October, while Iran’s oil exports fell by about triple that amount, around 1 million barrels per day.

Had the Saudis continued to drag their feet, prices might have neared the iconic $100 mark just in time for the U.S. election — handing Democrats a convenient talking point. Trump’s unilateral removal from world markets of 1.5 million barrels per day of Iranian oil would have looked masochistic, given that his sanctions deadline is just two days ahead of the Nov. 6 elections.

But global outrage over the Saudi critic’s murder has put the kingdom on the back foot. Allies and detractors alike, including normally friendly Republicans in the U.S. Senate, are baying for sanctions and an arms embargo.

While Saudi political leaders produced fumbling explanations for the murder, the oil minister stepped forward to change the narrative. Al-Falih promised another 300,000 barrel-per-day increase “soon” and said the kingdom still had another 1 million barrels of spare capacity it could call upon. If that weren’t enough, Saudi Arabia would consider investing in further capacity increases, he said. “We will meet any demand that materializes,” Al-Falih said Tuesday.

The comments calmed skittish markets, revealing that the oil minister, at least, is one Saudi official who retains credibility.

Is the kingdom rewarding Trump’s softly-softly approach? It’s hard to be sure. But the timing makes it look like the Saudis are banking that the president needs low gasoline prices more than he needs Riyadh in the penalty box.

The wild card is Erdogan. What depredations will emerge in the Turkish president’s next release? Will he finally release the alleged recordings of the gory murder and dismemberment in Istanbul?

Should that happen, Trump’s resolve could crumble. A forceful presidential response could revive Saudi threats to take “bigger measures” (read: oil) if the kingdom’s leadership were censured.

Although Al-Falih has stated that the kingdom has no intention of revisiting the the hardball tactics that brought us the Arab oil embargo of 1973, other Saudi policymakers have broached the possibility.

“If President Trump was angered by $80 oil, nobody should rule out the price jumping to $100 and $200 a barrel or maybe double that figure,” wrote Turki al-Dakhil, an ally of the Saudi royal court and director of the Saudi-owned Al Arabiya news network.

These were undoubtedly scare tactics. But coming from Saudi Arabia, scare tactics can put a scare into oil markets. Prices get notoriously jumpy when Saudi Arabia sheds predictability.

And if prices get jumpy, Trump’s Iran embargo would quickly be undermined by a sheaf of sanctions waivers, starting with Turkey and India, and then extending to others.

Pretty soon, the embargo starts to look like Obama’s, where import waivers were handed out because OPEC didn’t have the spare capacity to cover the loss of Iran’s exports.

Trump has a weak hand. He knows that the Saudis’ influence over U.S. gasoline prices gives them leverage in U.S. elections. Until the voting is done, bet on this: The president will find it hard to get tough on his Saudi friends.

Jim Krane is a fellow for energy and geopolitics at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Bill Arnold was a professor in the practice of energy management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Roller Coaster

What do analysts really know about stock ups and downs?

Illustrated by Nick Anderson. Based on research by K. Ramesh, Edward Xuejun Li, Min Shen and Joanna Shuang Wu

What Do Analysts Really Know About Stock Ups And Downs?

To learn more, please read: After Hours

K. Ramesh is the Herbert S. Autrey Professor of Accounting and Head of Accounting Programs at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University

Nick Anderson is a Pultizer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Changing Channels

Should your customers be using all of your channels to buy your services?

Based on research by Wagner Kamakura, Jesús Cambra-Fierro, Iguacel Melero-Polo and F. Javier Sese

Should Your Customers Be Using All Of Your Channels To Buy Your Services?

- Multi-channel customers are good for business, according to conventional wisdom.

- But when customers use every channel, the spiraling costs to accommodate them can slash profitability.

- The solution: Concentrate on high-margin channels or on certain channel combinations.

It’s never been so easy to spend. Or borrow. Or invest.

From an ATM on every street corner to downloadable apps to handshakes at the local branch, banks today are consumed with meeting customer needs through whatever channel is most convenient. All of which is good news for consumers.

What about the banks?

Conventional wisdom has it that multi-channel customers drive profitability. The theory is that varied sales channels increase the frequency of customer touchpoints, which in turn increase the number of opportunities to make a purchase. Then there’s the added value of increased convenience and comfort for the customer. This, together with the opportunity to combine multi-channel benefits, makes it more likely that customers will derive greater value — and therefore spend more.

But in practice, this doesn’t really work, says Rice Business Professor Wagner A. Kamakura.

Analyzing data from a leading European bank, Kamakura and colleagues from the universities of Pablo de Olavide and Zaragoza found that customers who make use of all the channels available to them are not, in fact, the most profitable in terms of margin. The reason: costs and efficiencies.

Kamakura and his co-authors parsed two years’ worth of transactions made by 1,000 customers across four major channels: online banking, point of sale transactions in retail outlets, ATM use and face-to-face interaction in branches. They analyzed three primary service areas: asset management, credit, and everyday banking services such as debit cards and insurance.

Recent research about purchasing had already challenged the assumption that multi-channel marketing is always a boon to business. While customers shopping for luxury goods typically generated higher profit by using multiple channels, that wasn’t true for people purchasing less expensive day-to-day products.

Kamakura and his team decided to test the same assumptions about banking services.

“We suspected that with goods, multi-channel use did expose customers to opportunities to purchase and spend more. But with services, the outcome would be different because of the costs associated with serving the customer across different channels,” Kamakura wrote. “We wanted to test the theory that overall profitability was tied to two things: the nature of the channel itself, and the quality of the customer-bank interactions each channel promoted.”

What they found was that when customers used all four channels offered by the bank, profits actually decreased.

“We call this the augmentation effect, where customers use a convenient channel leading to an increase in demand for services,” Kamakura explained. “This in turn leads to more costs but doesn’t create a corollary upsurge in the quality of customer relationships.”

On the other hand, when customers used a three-way combination of channels — point of sale transactions, branch banking and online services — profitability was markedly enhanced. Other permutations — branch and point of sale or branch and ATM, for instance — were also relatively good for business.

“There’s an interesting interplay and a complex dynamic when you combine certain platforms and set this in turn against cost implications to the business,” Kamakura said. “Where you see customers using a dual-channel combination of ATM and the branch, for instance, the net outcome is greater profitability to the bank. This is because it’s easy for customers to migrate routine operations to the ATM, reducing costs to the branch without impairing the human relationships with the bank.”

This human dimension offered by branch banking, he said, means that high-value transactions tend to happen here. And when high-value customers arrive at the branch, there’s an opportunity to cross-sell. This makes branch banking a high-margin channel.

Conversely, internet banking, while still relatively cheap to the bank, yields little in terms of relationship-building and makes it easier for customers to manage their own accounts — and switch service providers if they choose to.

In the age of AI and the seamless user experience, the implications of these findings for service firms are significant.

“It’s important to look at the big picture,” Kamakura said. “You need to be thinking about how technology and automation, self-service mechanisms might trim your overheads, but might also reduce your customer satisfaction. It’s about balancing and monitoring the tradeoffs between speed, efficiency, ubiquity and things like loyalty, behavior and emotions.”

Wagner A. Kamakura is the Jesse H. Jones Professor of Marketing at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Cambra-Fierro, J., Kamakura, W.A., Melero-Polo, I., and Sese, F.J. (2016). Are Multichannel Customers Really More Valuable? An Analysis of Banking Services. International Journal of Research and Marketing, 33(1), 208-212.

Never Miss A Story