Skin in the Game

Board members often need short- and long-term incentives to act in stakeholders’ best interests.

Based on research by Shiva Sivaramakrishnan and George Drymiotes

Board members often need short- and long-term incentives to act in stakeholders’ best interests.

- Boards of directors need both long-term and short-term incentives to motivate them to perform in a company’s best interest.

- Short-term incentives can prove particularly important to encourage board members to perform well at multiple roles.

- Board members who don’t receive short-term rewards may be more likely to overlook misconduct on the part of management.

If you’re a stockholder, you may envision your investment helmed by a benevolent, all-knowing board of directors, sitting around a long finely-grained wooden table, drinking coffee, their heads buried in PowerPoint charts as they labor to plot the best course for the company. Too often, however, you can’t take for granted that a company’s board will steer it wisely.

Companies choose directors because they offer rich and varied experience in the business world. Many who serve on boards, moreover, are CEOs of other corporations, or have headed big companies in the past. As of October 2018, for example, six of the 11 directors on Walmart’s board and eight of 13 on AT&T’s board hold CEO or CFO positions in other firms. So it’s easy to assume that board members will act in the best interests of stockholders.

But in a recent study, Rice Business professor Shiva Sivaramakrishnan found that board members actually need incentives — both short- and long-term — to act in stakeholders’ best interests.

Corporations usually compensate board members with stock options, grants, equity stakes, meeting fees, and cash retainers. How important is such compensation, and what sort of incentives do board members need to perform in the very best interests of a company? Sivaramakrishnan joined co-author George Drymiotes to trace how compensation impacts various aspects of board performance.

Recent literature in corporate governance has already stressed the need to give boards of directors explicit incentives in order to safeguard shareholder welfare. Some observers have even proposed requiring outside board members to hold substantial equity interests. The National Association of Corporate Directors, for example, recommended that boards pay their directors solely with cash or stock, with equity representing a substantial portion of the total, up to 100 percent.

To the extent that directors hold stock in a company, their actions are likely influenced by a variety of long-and short-term incentives. And while the literature has focused mainly on the useful long-term impact of equity awards, the consequences of short-term incentives haven’t been as clear. Moreover, according to surveys, most directors view advising as their primary role. But this role also has received little attention.

To scrutinize these issues, the scholars used a simple model, which assumes the board of directors perform three roles: contracting, monitoring and consulting. The board contracts with management to provide productive input that improves a firm’s performance. By monitoring management, the board improves the quality of the information conveyed to managers. By serving in a consulting role, the board makes managers more productive, which, in turn, means higher expected firm output.

This model allowed the scholars to better understand the relationship between the board of directors and the company’s managers, as well as with shareholders. The former was particularly important to take into account, because conflict between a board and managers is typically unobservable and can be costly.

The results were surprising. Without short-term incentives, the researchers found, boards did not effectively fulfill their multiple roles. Long-term inducements could make a difference, they found, but only in some aspects of board performance.

While board members were better advisors when given long-term motivations, short-term incentives were better motivators for performing well in their other corporate governance roles, according to the research, which tied specific aspects of board compensation to particular board functions.

Restricted equity awards provided the necessary long-term incentives to improve the efficacy of the board’s advisory role, the scholars found, but only the short-term incentives, awarding an unrestricted share or a bonus based on short-term performance, motivated conscientious monitoring.

The scholars also examined managerial misconduct. Board monitoring, they concluded, lowered the cost of preventing such wrongdoing — but only if the board had strong short-term incentives in place.

Even in the highest echelons of the corporate world, having skin in the game is what drives action. Maybe that’s no surprise. In business, personal stakes often dictate decisions — so stockholders need to scrutinize those at the top. Like everyone else, board directors perform best when they have something tangible on the line, not just distant rewards on the horizon.

Shiva Sivaramakrishnan is the Henry Gardiner Symonds Professor in Accounting at the Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To read more, please see: Drymiotes, G. & Sivaramakrishnan, K. (2012). Board Monitoring, Consulting, and Reward Structures. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(2), 453-486.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

It Takes A Town

B-to-B customers aren’t like retail shoppers. Here are eight ways to keep them satisfied.

By Vikas Mittal

B-To-B Customers Aren’t Like Retail Shoppers. Here Are Eight Ways To Keep Them Satisfied.

A version of this article was originally published by the American Marketing Association.

Senior executives at business-to-business companies strive to satisfy their customers to improve sales and margins. Yet very few systematic frameworks exist to guide their customer focus.

Last year, I was discussing the content of a B-to-B strategy course with the dean of a top-10 business school in Asia who lamented, “Most of what B-to-B companies do relies on recycled concepts from consumer companies. Consumer goods and services are focused on customer experience, customer delight and hedonic consumption, and rightly so. But B-to-B is different. It has so many utilitarian value drivers like sales, bidding, billing and project management that go beyond experiential aspects of value.” Simply put, B-to-B customers are different than traditional consumers of goods and services.

B-to-B companies have important differences from B-to-C companies. B-to-B companies typically sell complex products and services that are purchased by clients through a systematic purchase process involving multiple stakeholders, such as end users, evaluators and purchase managers. In terms of consumption, B-to-B cycles are long and complex — sometimes taking several decades and involving hundreds of employees.

B-to-B companies, therefore, must keep this glacial time scale in mind — and the unique customer needs such a scale entails. Research by scholars at Rice, Iowa State, and Texas A&M universities, on behalf of the Collaborative for Customer-Based Execution & Strategy, identified eight competencies specific to B-to-B customers.

Unlike functional competencies based on silos — such as manufacturing, finance, technology or innovation — these are based on perceived customer value. Functional competencies are still necessary to deliver this perceived value to the customer, but superiority on functional competencies alone is not enough.

The eight customer-based competencies are based on in-depth interviews and surveys of more than 600 managers and executives from the supplier and client sides in B-to-B firms. They include:

1. Bidding and Sales Process

While retail customers make quick decisions based on price tags, B-to-B customers typically go through an elaborate bidding and sales process. Throughout the process, they evaluate the sales team’s competency and the suppliers’ ability to provide accurate proposals. In interviews, customers described the process in one of two ways: either “We get a lot of work from relationships that our sales force develops,” or “Salespeople need to do a better job understanding our needs so that the proposals are streamlined to our needs.”

2. Quality of Product and Service

Products and services in B-to-B can range from multiyear service contracts to complete power plants. For B-to-B companies, quality is based on customers’ perceptions of how well the supplier’s core offerings perform. Customers describe this competency as “meet(ing) performance specifications for the equipment and the service employees.”

3. Billing and Pricing

Customer perception of whether a firm’s pricing and billing processes are fair and competitive goes beyond low prices. Respondents report that they “don’t like companies that low bid and then issue change orders to jack up the price.” They also express frustration when “accounts payable has to go back over the billing because it is wrong about half of the time.”

4. Communication

In B-to-B relationships, communication is a core component that can lower perceived customer value when derailed. We define communication as the extent to which a supplier shares appropriate and accurate information in a clear and timely manner. Customers describe companies that excel at this competency as “providing the attention required to keep accounts happy, especially the large ones.” In contrast, firms with poor communication are described thus: “Everything is email. I get zero in-person contact with them.”

5. Safety

Assuring the safety of products, customers and employees is a critical competency, especially in B-to-B contexts involving the oil and gas industry, manufacturing, transportation, nuclear energy and waste management. For example, the Deepwater Horizon disaster ensnared BP for several years. Customers describe safety as one of the major issues in complex jobs, saying “TRIR (Total Recordable Incident Rate) is very important.”

6. Project Management

Suppliers must be able to adequately help plan, execute, and support the initiatives and projects they are involved with. One of our interviewees mentioned that project management is an essential part of the business, explaining that “thousands of policies and procedures need to be followed to execute a project.”

7. Sustainability and Social Responsibility

Sustainability and social responsibility represent customer perception of the extent to which a supplier voluntarily incorporates societal and stakeholder concerns in its value proposition. In describing the benefits of these competencies, customers say: “I know they are not doing anything dirty — they help us stay on the right side of [the Environmental Protection Agency],” and “It is important to be a community partner by creating local jobs. We always emphasize local content and training.”

8. Ongoing Service and Support

Just because you’ve already sold a product or service doesn’t mean you’re done; service and support must continue into the consumption phase of a B-to-B relationship. In marketing, this has been described as after-sales service, as well as ongoing relationship management. It’s different from the customer’s initial assessment of the product or service quality. In interviews, managers stressed the importance of ongoing service support. One said, “For many contracts, we will need to have a guarantee that no issues will be happening after delivery.”

Our research shows that these eight attributes make up a whopping 70 percent of customer value, as measured by overall customer satisfaction. Across a wide swath of industries, these are integral predictors of sales and gross margins — even after statistically accounting for a variety of customer factors, such as purchase amount and involvement; company factors, such as size and firm risk; and industry factors such as the competitiveness of the field. Meeting customer needs through these eight competencies, therefore, also satisfies shareholder goals.

For B-to-B companies, competitive advantage lies in these eight unique competencies, which are specific to business contexts. Delivering each competency will require a cross-functional approach that cannot be achieved by excelling in only marketing, finance, innovation, service or sales. For example, excellence in departments such as project management requires engineering, manufacturing, customer service, accounting, and even sales. To get these departments to work together, companies will need to accurately measure their role in each of these competencies and link them to sales and margins. Done well, this can provide a roadmap for achieving meaningful improvements in both customer value and shareholder performance.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing and Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Don't Let Me Down

Think customers crave delightful extras? In fact, they report more satisfaction when firms simply avoid disappointing them.

By Vikas Mittal

Think Customers Crave Delightful Extras? In Fact, They Report More Satisfaction When Firms Simply Avoid Disappointing Them.

This article was originally published by the American Marketing Association.

Many executives believe that delighting customers will improve their satisfaction and increase sales, but few can say how exactly to meet (and exceed) their expectations. Often, they think satisfying customers is a subjective exercise that cannot be precisely defined or measured. But both are possible by examining what satisfies and dissatisfies customers.

For the last two decades, I’ve developed statistical algorithms to measure “satisfier” and “dissatisfier” attributes. My colleagues and I have analyzed hundreds of attributes in dozens of industries to reveal how satisfiers and dissatisfiers can be used to understand customer satisfaction.

Satisfier attributes — also called “delight attributes” — tend to be hedonic, sensory, “nice to have” amenities that are not considered critical to the functionality of a product or service. At a hotel, a chocolate on your pillow would be a satisfier attribute. Dissatisfier attributes are fundamental must-haves that deliver the basic utility customers expect from the product or service. At a hotel, a clean bathroom would be a dissatisfier attribute. At a doctor’s office, an accurate diagnosis is a dissatisfier attribute, while a polite receptionist may be a satisfier attribute.

When it comes to satisfier attributes, a strong performance improves customer satisfaction a lot more than poor performance hurts it. That is to say: Above-average performance has a disproportionately higher positive effect on satisfaction than the negative impact of below-average performance.

In the oil and gas sector, sustainability and social responsibility are satisfier attributes, for example. Going above and beyond expectations on these attributes can have a disproportionately greater impact on customer satisfaction than would the negative impact of doing too little.

Below-average performance on dissatisfier attributes, however, hurts customer satisfaction much more than above-average performance would improve it. In other words, below-average performance on a dissatisfier attribute is more harmful for overall customer satisfaction than the benefit from above-average performance.

Communication is a dissatisfier attribute among oil and gas customers; the negative impact of below-average communication on satisfaction is disproportionately larger than the positive impact of above-average communication.

Companies that want to maximize customer satisfaction, therefore, should focus on reducing below-average performance on dissatisfier attributes. In general, the negative impact of dissatisfier attributes is twice as large as the positive impact of satisfiers. Companies that want to avoid steep declines in overall customer satisfaction should start by minimizing below-average performance on dissatisfiers. Simply put, delighting customers with satisfiers does not compensate for dissatisfying customers with subpar performance on the fundamentals.

Customer experience management is especially prominent in the services sector, with brands such as Ritz-Carlton in hospitality, Sears in retail, JPMorgan Chase in financial services, Ford and Toyota in automotive dealerships and Disney in entertainment. These brands emphasize the sensorial and hedonic aspects of the interaction between brand and customer; the goal is to endlessly please and delight customers by continuously exceeding their expectations. Bloomberg reported on employees at a Ritz-Carlton in Bali who demonstrated this concept when a child with food allergies arrived as a guest. The child required special eggs and milk that could only be obtained in Singapore. The staff called in personal favors and brought in the specialty food from more than 1,000 miles away. This increased the overall customer satisfaction disproportionately higher than if the staff had made a subpar effort to accommodate the child.

Based on this anecdote, should all companies strive to maximize positive performance on all attributes to delight customers? No.

In most cases, trying to continually exceed customer expectations is going to be unrealistic and unprofitable. As customers come to expect more of you, delighting them becomes progressively more difficult and costly. It will require an astronomical investment to maintain these efforts — investments that will squeeze margins and dramatically raise the cost of doing business. Despite the increased cost of delighting customers, competitive pressures will preclude most firms from raising prices to offset these increased costs. Eliminating dissatisfiers, on the other hand, is less costly to implement, easier to sustain, and provides a durable cost advantage.

A B-to-B company we worked with found that customers expected their order to be fulfilled within two weeks. Previously, this company had attempted to delight some customers with rush orders that were fulfilled in less than two days — but others were taking more than three weeks. The average fulfilment time was a week and a half, yet many customers were still dissatisfied when their order took more than two weeks.

Based on our recommendation, the company implemented a strategy to minimize below-average performance by fulfilling every order in fewer than 12 days. It eliminated its policy of rushing orders to delight customers and replaced it with a goal to ensure all orders were met within the 12-day limit. By eliminating rush orders, the company not only saved resources but also improved overall customer satisfaction, leading to an 8.3 percent increase in sales and a 14.6 percent increase in margins.

My colleagues and I also counseled executives from an oilfield-services company that treated communication as a satisfier attribute. Its sales team and customer service representatives were communicating with customers as often as possible in as many ways as possible. Customers received an average of five communications per week, including customer surveys, service representative calls and messages and requests from salespeople to arrange demo meetings for new products. Rather than delighting customers, the communication fatigued and dissatisfied them. Executives were surprised to learn that communication was a dissatisfier, not a satisfier, for its customers.

Further research showed that the optimal communication frequency was one touch point every two weeks, or two communications per month. By going from 20 touch points per month to two, this company decreased its cost of doing business by 20 percent and simultaneously increased sales and maximized customer satisfaction.

The takeaway? Because losses loom larger than gains, most customers are looking for value that comes from consistently meeting expectations, with few, if any, major letdowns. A strategy of minimizing disappointments runs counter to the oft-touted principle of customer delight, which can inflate customer expectations, erode margins, and cost more than it’s worth.

To identify dissatisfier attributes, a company must have a clear and consistent measurement strategy that links attribute performance to overall customer satisfaction. This requires a deep understanding of the attributes that drive customer satisfaction, competency in developing customer surveys and fluency with advanced statistical analysis. But the payoff is huge: Customers are more satisfied and companies can increase sales and margins while using fewer resources overall.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing and Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Satisfaction Guaranteed

How price adjusting eases consumer regrets.

Based on research by Amit Pazgal and Dinah Cohen-Vernik (a former Rice Business professor)

How Price Adjusting Eases Consumer Regrets

- When an item’s price drops after purchase, offering the consumer a price adjustment brings higher profits to retailers.

- This strategy remains powerful even when all shoppers end up asking for and getting refunds.

- To boost these profits, retailers should consider variations in the size and timing of their refunds.

You finally bought your dream TV online from Best Buy. Then, a week later, heartbreak: The Best Buy a mile from your house lowered the price on your TV by $200. You notice, you gnash your teeth, you wish you had gotten your big-screen somewhere else.

Luckily, price adjustment is a favorite tactic of retailers who are determined to justify your love. As Best Buy promises on its website: "If we lower our in-store or online prices during the return and exchange period, we will match our lower price, upon request."

Such policies successfully win the hearts of shoppers. But how do they affect the retailers?

Let’s go back to Best Buy. A prospective TV buyer goes into a Best Buy, finds a TV she likes and considers buying. She wavers, thinking the price might come down in a week or two. She finally walks out without buying. Maybe she comes back. Maybe she doesn’t.

Another shopper goes to a Best Buy, finds a TV she likes and considers buying. She asks the salesperson if she can get a refund if the price falls. When she hears the policy details, she buys on the spot.

Though it seems to benefit mainly the customer, price-adjustment is also a powerful tool for retailers: it increases their profits even if all consumers request and get the adjustments, Rice Business professor Amit Pazgal and former professor Dinah Cohen-Vernik found.

Price adjustment is related to, but different from, price matching, which is when a retailer vows it will not be undersold and matches prices from competitors. Price matching took off in the early 1980s and has been well-known and commonly used ever since.

Price adjusting is a newer, and purposely lower-profile, strategy, the Rice researchers noted. Using a series of complex equations and consumer surveys, they concluded that price adjustment is likely to generate higher retail profits in a wide range of scenarios.

The key is to tailor these adjustments, the researchers said. They noted the example of Lamps Plus, with its offer of a "120 percent low price guarantee" for 60 days after purchase. If a customer wants to take advantage of this offer, the outlet matches the lower price and also returns an extra 20 percent of the difference to the customer. (Say you paid $100 for a lamp, and it goes on sale the following week for $90. You’re entitled to $10 back off the bat — plus 20 percent of the $10 difference. The total price adjustment is $12.)

The optimal refund amount depends on how patient consumers are. Do they want the newest phone model now, or can they wait weeks for it — or even forgo the purchase? If the need-it-now factor is higher, retailers can boost profits by offering price adjustments of less than 100 percent.

Whatever the case, the authors emphasized, the retailers benefit from a price adjustment even when all eligible customers scoop up their refund. That’s because even the promise of a refund influences the timing of a purchase. When customers aren’t worried about missing out on future discounts, they’re more likely to buy on first impulse.

This finding also suggests that retailers ought to advertise their price adjustment policies more aggressively. Advancing this line of thought further, the researchers floated the intriguing idea of automatic refunds — but under a specific circumstance.

“When consumers tend to underestimate their likelihood of requesting the refund, offering an automatic (unrequested) price difference refund to consumers improves retailer’s profits,” they wrote. And an unrequested refund might provide the added benefit of a PR boost, they said.

Currently, most retailers only offer price adjustments during one limited window — for example 14 days at Target or 30 days at Sears. But that shouldn’t be the only model, the researchers said.

Back to Best Buy one more time, where yet another prospective buyer is hunting for her dream TV.

She’s drawn to a sleek model priced at $1,200. The thrifty voice in her head warns that the price will surely come down over time, maybe more than once. She wants the TV now, but does she need it? She turns to leave empty-handed.

If the retailer had taken cues from the Rice research, however, a salesperson would speak up before the thrifty voice in the shopper’s head could get a word in edgewise. If the price fell by $200 in two weeks, the shopper would learn, she’d be eligible for a $200 refund. And if the price fell again by $200 in the four weeks after that, she’d be entitled to another $200.

The thrifty voice would be happy. The gratified customer would haul her new TV away in triumph. And if the retailing strategy fulfilled all its potential, the thrifty, gratified consumer would tell the world on Facebook where to buy a TV like hers — price adjustments guaranteed.

Amit Pagzal is the Friedkin Chair in Management and Professor of Marketing and Operations Management at the Jones Graduate Business School at Rice University.

Dinah A. Cohen-Vernik is a former assistant professor of marketing at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more please see: Cohen-Verninck, D., & Pazgal, A. (2017). Price Adjustment Policy with Partial Refunds. Journal of Retailing, 93, 507-526.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Railroad Ties

Remembering Ed Williams, the person who laid down the tracks of entrepreneurship at Rice Business.

By Weezie Mackey

Remembering Ed Williams, The Person Who Laid Down The Tracks Of Entrepreneurship At Rice Business

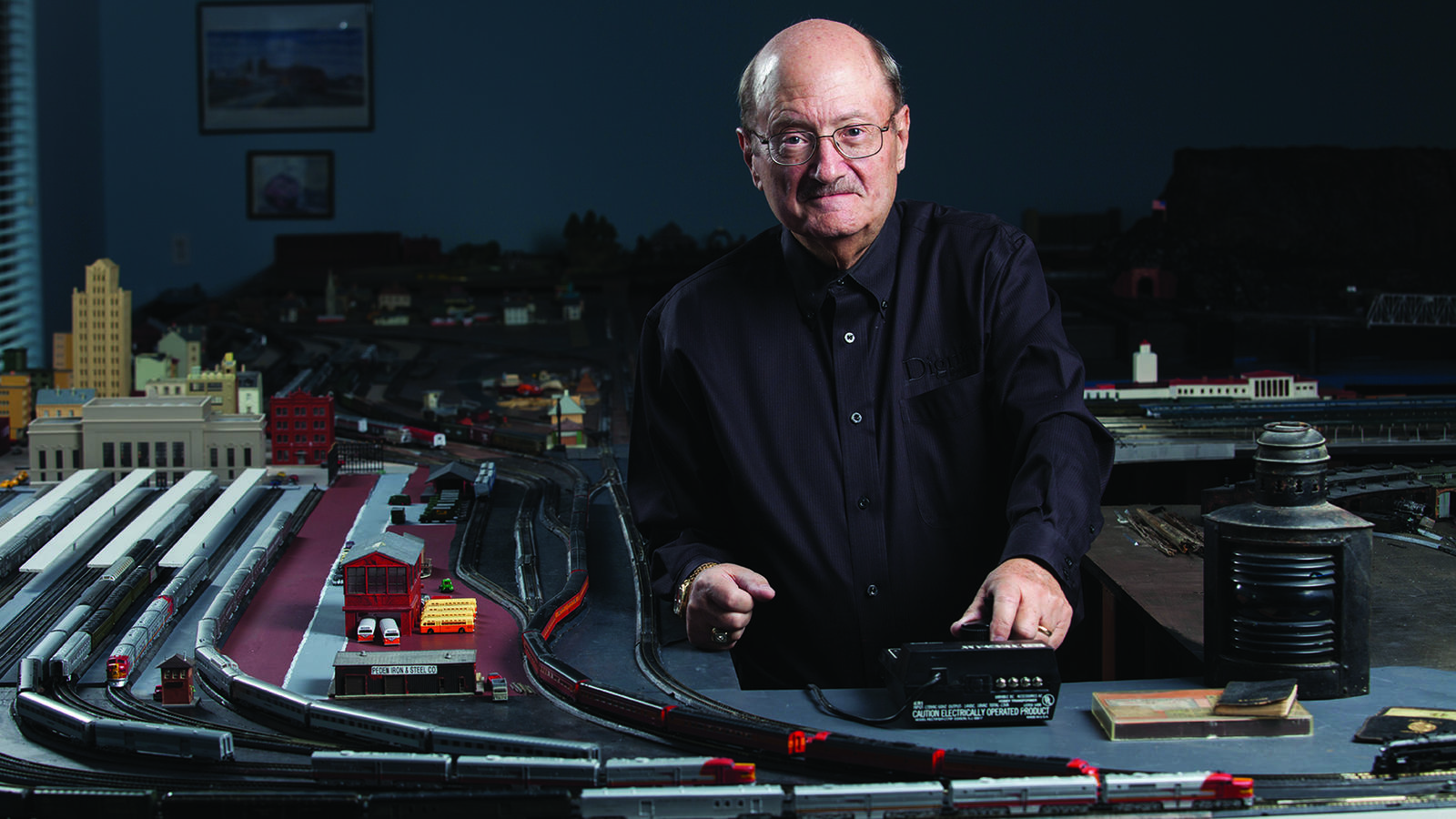

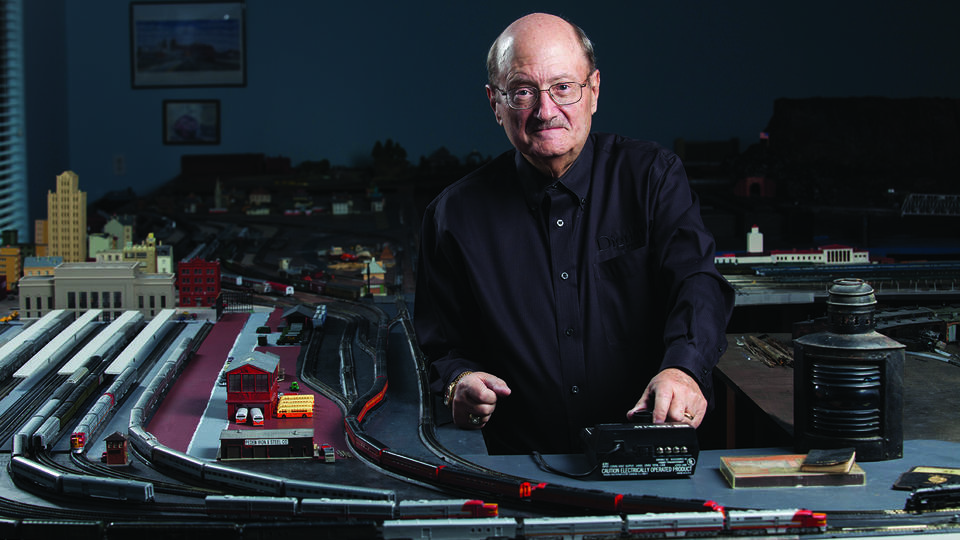

In remembering the life and legacy of Professor of Entrepreneurship (Emeritus) Ed Williams (1945-2018) we are republishing an article from the Spring 2015 edition of the Jones Journal in his honor.

Ed Williams grew up in Houston and discovered early on that he had a knack for selling

At age seven he started putting old magazines in the back of his wagon and knocking on doors. “Half the people would slam the door in my face. The other half would listen. A few would buy used magazines. I’d make another round in another neighborhood, ‘do you have any old magazines you’d like to get rid of?’ My cost of goods sold was zero,” he said, revealing the first inklings of an audaciously entrepreneurial childhood.

Williams’ father worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad. When he was old enough, he took school excursions to Austin or San Antonio once a year. “My dad would lend me $5. I’d buy curios on the trip and then go through the train on the way home selling them to kids or trading. I’d come home with at least $25. One time I had some extra inventory, and I went to see Carl Cohen who owned the little grocery store around the corner from where I lived at 14th and Studewood. He liked me. I asked Carl, would it be all right if I sold some of these things outside his store? He said yes, so I set up my little stand and sold out the first day. I was 10.”

From a little red wagon to crossing the border into Juarez to buy exotic inventory — Mexican bats and bull whips — Williams built a business and an entrepreneurial acumen one sales trip at a time. Today, at 70, always ready with a story, it isn’t hard to imagine the blond-headed kid with the gift of gab who readily admits he had better luck selling to women than men. There would be no holding him back.

Mentors made the difference

As of July 1, 2014, Ed Williams — formerly the Henry Gardiner Symonds Professor of Management — retired from his career teaching entrepreneurship at the Jones School. He estimated that he taught about 3000 students in 100 courses in 36 years, including the first graduating class — all together more than half the alumni. It’s no wonder so many of them have stories to share. And that Williams has even more.

Somehow, the war stories of entrepreneurship stick. Whether it was born from necessity or desire, his entrepreneurial approach shaped him as a scholar and an educator.

“I knew from a fairly early age that I was going to be looking after myself by the time I was 17 if not sooner,” Williams said. “My dad was a yard master with SP. He was out in the field originally but became a freight re-check clerk, examining mileage and commodity records. He was born in 1897, lived through both World Wars and the Depression. My dad was very conservative. You don’t live through two wars and a depression and come out a risk taker. His own history had a lot to do with mine because the people who worked for the railroad never made a lot of money, at least not at his level. It was sufficient to live on but not to pay for college.”

Through hard work, pluck and several formative relationships during his life, starting with store-owner Cohen, Williams made his way in the world. And then some.

As a student at the newly built Waltrip High School, he became a little less entrepreneurial and a little more studious. After a few summers as an archives clerk at the Magnet Cove Barium Corporation, he landed a plum summer job through his aunt at University State Bank, working as a sight payer and bookkeeper. “The man who owned the bank was a fellow named Goldston. He asked me what I was going to do with my life?” Williams explained that he was saving to go to college. Goldston invited him, after work and on his own time, to come up to his office and learn to read the Wall Street Journal. “We started on page one. While he was teaching me how to read the Wall Street Journal and the quotations and prices,” Williams said, “he was also teaching me how his bank operates. It was fascinating.”

During his senior year of high school, while president of the student council, Williams was introduced to Bob Waltrip, the owner of Heights Funeral Home. A lifelong friendship began that day as Waltrip shared his plans for Service Corporation International (SCI), where Williams would become vice president years later. First, of course, the budding business man had to go to college. He studied economics and finance at Wharton at the University of Pennsylvania. “I got through Wharton in three years because I ran out of money,” Williams said. After graduation, when Waltrip asked him if he was ready to come work, Williams said, “No. I like academia. He told me he thought I was making a serious mistake.”

The fast train

After looking into and deciding against graduate school at Yale — it was longer and more expensive than what he could afford — Williams got a hold of the head of the finance department at the University of Texas. “The tuition was $50 a semester for all the courses you could take. There were no constraints on time. You had to pass five field exams and write a dissertation. And you had to take so many course hours. I signed on and finished my Ph.D. in two years. I was 22.”

He shrugs and claims it was a matter of necessity. “I had no money. I got the Texas Savings and Loan League fellowship and ultimately wrote my dissertation on the savings and loan industry. I remember one semester I was taking seven courses. I was teaching two and writing my dissertation. And living on a $100 a month.”

As he was finishing his doctorate, Williams attended the American Economic Association meeting and ran into a former professor of macroeconomics from Wharton, Paul Davidson, another mentor who remains a good friend to this day. “I was looking for a job. He was a professor at Rutgers by then. He said, ‘You’d be younger than the kids in our graduate school, but why don’t you come up and give a paper, and we’ll see how it goes.’ It went well.” He was hired as an assistant professor of economics in the College of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers. After two years he was hired as an associate professor of finance in the Faculty of Management at McGill University.

Three years later he called Bob Waltrip. SCI had gone public in 1969 and was doing very well. He told Waltrip he was ready to leave academia for a while. “I went down to visit and got a job offer to be a vice president. It was three times what I was making at McGill plus stock options. This was 1973. My basic job was to oversee our investments, including our endowment care funds and still am today as chairman of the investment committee of our board of directors. In those days, we had $9 million. Now we’ve got $9 billion.”

Today, SCI is the world's largest operator of funeral homes and cemeteries in North America, and Williams worked there five years before he got a call from the first dean of the Jones School, Dr. Robert Sterling, asking if he might be interested in returning to academia.

“I said to Sterling, if I come back to academia, I’m not interested in teaching finance and economics. I did that already. I want to do something different.” Which is how Williams arrived at Rice as the founder of a new program in the emerging area of entrepreneurship. It was 1978, and Williams was 33.

Head of the class

Only a handful of business schools were teaching entrepreneurship back then. “The exciting thing about that time was the Jones School was new,” said Williams. “The upshot of that was you could mold it.” Molding it meant finding literature and textbooks, creating a curriculum. “There was a textbook being used, Patrick Lyle’s The New Enterprise. He was an adjunct at Harvard. It was a case book, but it had snippets of the theory of entrepreneurship. Which is almost an oxymoron. I spent the summer with that book preparing to teach the fall class, The New Enterprise. The spring class would be Buying and Selling Companies.”

Williams loved being back in the classroom. “I like talking to people and explaining things. It’s funny because even when I was in junior high I would pretend to be a teacher. I would stand up with a little black board and teach Texas history or something like that. I pretended that I had students. I even graded fake papers.” He laughed. “I’d write stuff up with mistakes in it and grade it. I always wanted to be a teacher.”

The second year he added a third class. “My agreement with Bob Sterling was I could teach two the first year and three the second. The added class was micro-economics, which I didn’t really want to teach, but I did, and I met my wife Sue in that class. She was a student,” he smiled. “But nothing happened until later.” Susan ‘84 had two children, Laura and David ‘99, and a dog from a previous marriage. The two married in 1983 and now have five grandchildren.

In 1979, Williams attended the first Babson College Entrepreneurship Conference to see what other business schools were doing. Rice was in good company. Harvard, UCLA, USC, Carnegie Mellon, Wharton and Babson were the universities that pioneered the development of this new discipline, and they were all in attendance. Next, Williams began to recruit the first of many adjunct faculty members who were instrumental in the early success of the program. The first was George Ballas, inventor of the Weed-Eater, who team taught the New Enterprise course with Williams.

The question remained: can you teach someone to be an entrepreneur? “My thinking on that is it’s a practice. You learn to be an entrepreneur by having done it for a while. You can structure an analysis of it, almost like a social scientist looks at a phenomenon. Actually teaching somebody to be an entrepreneur is a different story. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be put in a formal framework and examined.”

Enter Al Napier

When Al Napier began teaching Information Technology at the Jones School in 1984 there were still only 15 full-time faculty members. Williams had known Napier as a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin in the ’60s. They struck up their old friendship and began fishing together. On one of their trips, they talked about Napier joining the entrepreneurship faculty. “He had his computer consulting company, Napier and Judd, but we were getting to the point where the classes were getting larger and larger. I wanted help teaching The New Enterprise. It kind of brightened my day because needing another professor showed the entrepreneurship program was working.”

It brightened Napier’s day as well. “Ed has been a great friend. He mentored thousands of students and alumni with their entrepreneurial pursuits and mentored me in my teaching of entrepreneurship,” Napier said. “His impact has been immeasurable.”

Being bigger gave the Jones School the opportunity to claim some fame in the world. “Businessweek came down here,” Williams said modestly. “They nominated a few people back in ’96 for top entrepreneurship professors, and I was No. 2.” In the country. Not only that, but he won so many teaching awards within the school, that he eventually declined to be in the running so that others could take home the honors.

The rest is history. After Napier accepted the position, and The New Enterprise course ultimately became his, more adjuncts were hired, including Jerry Finger, a successful banking and real estate entrepreneur, and Dennis Murphree, a serial entrepreneur who was also a savvy venture capitalist.

From one faculty member teaching two courses in 1978, the program now has over 23 faculty members teaching 27 entrepreneurship-related courses. The year 2013 marked the naming of the Ralph S. O’Connor Associate Professor in Entrepreneurship, awarded to Yael Hochberg, and a schoolwide entrepreneurship initiative, for which she is executive and academic director.

Go out and learn a business

Williams walked among a sea of students in the Rice Memorial Center, looking professorial. He came from a course in statistics and investments that he was teaching with John Dobelman. “It’s through the statistics department. He’s the professor in charge, and I go over and lecture some. Once a week, three hours. Gives me a chance to stay in touch with students. I like the lecturing. I do it for free. I do it for me.”

Though the two just wrote a text book together — Investing for Profit: A Data Based Approach — the teaching of entrepreneurship never seems far from his heart. “I used to try and leave the students at the end of the year with this advice: go out and learn a business. Know that business. Then buy one in that area. Jack Ledford did that. Even though he’s military and has a financial background. He actually got his feet wet in the operations of a business.”

Ledford, class of ’02 and CEO of Spearhead Services, added, “Ed’s class really opened my eyes to a whole world I didn’t know existed. I realized that’s what I needed to do. He taught us it’s about the balance sheet not the income statement. Managing the balance sheet is the answer. He’s been an investor in two of my companies. A lot of people don’t put their money where their mouth is. He does.”

Cooper Etheridge, class of ’03 and president of Automation Technology Inc., agreed. “He was the very first person to invest in my business, proving that he is willing to practice what he teaches. Ed represented a breaking away from the usual and mostly theoretical approach of our other classes. He emboldened his students, and made us feel, while we were in school, that we were already in the game and to start acting like it.”

Williams scowls at what he sees as his own limitations. “It’s still not sufficient. A student could take my class. They know all the tricks of buying and selling but they still don’t necessarily know how to operate a business. Buying and Selling is easier, but it’s still not a substitute for knowing how to run something.”

Sometimes he had a student with some kind of experience. Take Caroline Caskey Goodner ’92, CEO of Caskey Holdings LLC, as an example. “Her father is a physician. He’s also quite an inventor and entrepreneur. Her mother is as well. She grew up in an environment of ‘let’s start a business. Let’s do this.’ And, believe it or not, that helps.”

Goodner said, “Ed’s class and his enthusiasm for entrepreneurship was the catalyst for me starting a company after graduation. I had no intention of pursuing entrepreneurship when I entered business school, but after catching his passion for being an independent employer and employee, I decided to start the company I had devised in a business plan during his class.”

And business plans are vital. But it is Williams’ belief that while the skillset of being an entrepreneur is teachable, “Being one is not.”

On the horizon

Rob Royall ’84, a partner at Ernst & Young, said Williams offered this advice in one of his classes: the key to success and building wealth is to find something no one else wants to do and become very good at it. “When I pursued an expertise in derivatives accounting, there was literally one person in all of Ernst & Young who was deeply experienced in it. I eventually became his successor and the leader in the firm on the topic—the topic no one else was clamoring to cover. They made me a partner in order to get coverage on the topic and the risk it presented to our practice.”

That kind of advice and the practical foundation he provided has made the entrepreneurship program what it is today. It is the legacy he leaves in his wake. His free time is jammed packed with golf, the investment committee at SCI and his own personal investments, teaching with Dobelman, the model railroad set that takes up 1,500 square feet and hundreds, possibly thousands, of feet of track.

The idea of the train set was to give him something to do in his 70s and 80s. “When I was a kid, we went everywhere on the train because we had a free pass. That was the way we got around. We didn’t even have a car. So I’ve always been interested in trains. Always enjoyed riding them. Even to this day I love to take a train.” The elaborate train is a replica, of sorts, of the Southern Pacific’s main line, which ran from New Orleans through Houston to El Paso and Los Angeles, Oakland and San Francisco, and then all the way to Oregon. “I started with Houston and made big passenger stations, including the two in Houston – Union Station and the SP's Grand Central Station. I now have every train the SP railroad had from that era.”

The historical precision of stations and cities from the 1950s — he’s working on Los Angeles now — requires a strategic perspective and the constant care and maintenance of a master gardener. “I like operating them. I enjoy putting them together and planning what will go where.”

From his first entrepreneurial adventures to the meticulous model railroads, Ed Williams looks much the same in retirement as he did in the first blush of his career: there’s no holding him back.

Ed Williams was a Professor of Entrepreneurship at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University. BusinessWeek named him one of the top two of the nation's best entrepreneurship teachers. He believed exposure to entrepreneurship is essential to a business education.

Weezie Mackey is the Associate Director of Marketing and Communications at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Let It Go

Anger over oil prices won’t change OPEC’s resolve.

By William M. Arnold

Anger Over Oil Prices Won't Change OPEC's Resolve

This op-ed originally appeared in The Hill.

Oil prices are again on the minds of statesmen and executives as world leaders convene at the U.N. General Assembly in New York. Suffice it to say, these are not the 1970s, when oil-shortage angst gripped the United States and Presidents Nixon and Carter urged the nation to make serious sacrifices.

Let’s review what’s going on: Brent oil prices, associated with production in Europe’s North Sea, have exceeded $80 per barrel, the highest since prices collapsed four years ago.

Production constraint by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Russia, growing world demand and sanctions on Iranian production have contributed to this surge. This is taking place despite record U.S. production of 11 million barrels a day, which is flooding and disrupting markets.

President Trump has called on OPEC and its allies to increase production to lower gasoline prices, and he has threatened to use the country’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve to unilaterally lower U.S. prices.

But the OPEC/Russia cartel, well aware of how vital oil is to its economies and prestige, has a new vision of its future that they hope will drive prices higher.

Predictions of oil prices are fraught with casualties. Oil prices might again reach $100, but is that next month or five years from now? Pundits brag about the occasional accurate forecast while remaining silent about those that didn’t materialize.

Many factors impact oil prices, ranging from geopolitical risks like Iran, production costs in different countries, shifts in markets (more production in the U.S., more demand in Asia), technical issues like refinery configurations and capacity and logistics. (Brent is already sea-borne while West Texas is landlocked.)

Currently, Brent prices are about $10 per barrel higher than West Texas Intermediate related to U.S. production. Traditionally, there has been only a modest gap between the two, and the balance shifted frequently.

But after the shale boom erupted a decade ago, there was insufficient U.S. pipeline and refining infrastructure near the producing areas. As a result West Texas oil sold at a $23 discount to Brent in 2012.

At the same time, Brent prices were inflated by perceived heightened political risk in the Middle East. That spread dissipated until late last year.

Markets determine prices, and they fundamentally reflect supply and demand, just as we learned in Econ 101. The more interesting question is who and what impacts supply and demand?

The story of the last decade has been the surge in U.S. production and the OPEC/Russia response to it.

The U.S. has become the world’s largest producer of crude oil after eroding in the 1980s and 1990s from a high in the 1970s. Much of this comes from the “shale play,” which combined horizontal drilling with hydraulic fracturing.

Skeptics expected operational costs and infrastructure challenges to cause production to peak and decline. Instead, shale has transformed into a manufacturing process based on constant adaptation of technology and cost reduction.

OPEC, Russia and others were deeply concerned about these new additions to oil markets at a time when global demand was just rebounding from the global financial shock of 2008-2009. OPEC chose to maintain production levels, which combined with the new U.S. production, tanked oil prices from highs near $120 to levels below $30.

Conventional wisdom suggested that shale production costs were around $70, so production was expected to diminish drastically at much lower prices. There was turmoil in the market. Hundreds of corporate bankruptcies took place in the U.S. and more than 200,000 jobs were lost globally.

But the U.S. industry, pressed against a wall, found ways to lower breakeven costs and generate cash flows, often in the $40 price range.

OPEC, Russia and related countries this time responded by agreeing to production cuts that reflected unique characteristic of member nations. The tradeoff was straightforward: Cut production by "X" but world prices rise by "2X" — and the bottom line grows.

To the surprise of market skeptics, the agreements held and were renewed. Now OPEC/Russia see potential for their production to increase as a substitute for reduced Iranian production. But the cartel has not forgotten recent lessons and, under Saudi leadership, is moving judiciously.

As U.S. production reached 11 million barrels per day, infrastructure and operational constraints have been a constant challenge.

There is a huge need for water, for the right kind of sand, for trucks and truck drivers, for rig crews, for pipelines to move oil and the natural gas associated with its production and for export facilities.

This impacts the ability to get it to market and accounts for some of that $10 spread between Brent and West Texas Intermediate prices.

President Trump, not unlike other U.S. presidents at a time of rising gasoline prices, sees a political problem. He proposes using the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to add to production and lower gasoline prices.

The reserve was created, as the name implies, to use in emergencies and not to manage prices. In any case, the reserve is finite and relatively small in terms of U.S. demand. It would be a short-term measure at best.

This week, he has been jawboning OPEC about its production controls. While the markets are free, OPEC is a cartel and, along with Russia, has learned a lot in the past decade about its impact in the face of resurgent U.S. production. It will act in its own perceived interests.

Additionally, the president’s use of tariffs may have unintended consequences. Tariffs on steel impact the capital and operational cost of oilfield production, reducing profit margins and possibly longer-term investment that can restrain U.S. production and raise prices.

Retaliatory tariffs by China on U.S. liquefied natural gas can hurt growing U.S. exports and favor countries as disparate as Qatar and Australia. If a trade war escalates, this could dampen global demand for all products and lower energy prices, but that would be associated with slower global economic growth.

Policymakers — in the U.S. and abroad — need to understand the complexity of this market and the constantly changing dynamics as they consider executive actions, legislation or regulation.

Every action will cause a reaction, but it may not be equally strong. For now, President Trump would be best advised to let the markets play things out. The country is certainly not as handicapped in energy matters as it was in the 1970s.

Bill Arnold was a professor in the practice of energy management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Outside The Box

To come up with new ideas, it helps to think outside the box — but which box, exactly?

Based on research by Erik Dane, Markus Baer, Michael G. Pratt and Greg R. Oldham

To Come Up With New Ideas, It Helps To Think Outside The Box — But Which Box, Exactly?

- Many researchers have presumed that intuitive thinking enhances creativity because it is less methodical than rational thinking.

- Dane and his colleagues found that the thinking style itself mattered less than whether it’s what you typically use.

- Normally intuitive thinkers came up with more creative ideas when they tried rational thinking.

Creativity is an essential ingredient in problem-solving, and the importance of “thinking outside the box” has been stressed in nearly every context imaginable, business or otherwise. But that mantra assumes — wrongly — that we all start off thinking inside the same sort of cognitive box.

Instead, each person has a distinctive cognitive style: Some of us, for example, are more intuitive, and others approach the world more rationally. What happens to creativity when those who use a particular thinking style tried a different approach?

Former Rice Business Professor Erik Dane decided to investigate. Along with colleagues Markus Baer of Washington University in St. Louis, Michael Pratt of Boston College, and Greg Oldham of Tulane University, Dane studied typical thinking styles, rational versus and intuitive, and how resisting the most familiar one can affect creativity.

Rational thinkers, the professors noted, learn information deliberately and engage in thoughtful analysis. They depend on a linear, or sequential, way of processing information. Intuitive thinking, meanwhile, is an unconscious way of processing information. It’s essentially the opposite of rational thinking: quick and holistic, rather than deliberate and comprehensive.

When a rational thinker faces a problem, her mind goes through multiple stages, tapping relevant mental data bases and coming up with alternative solutions. Her mind evaluates and refines these scenarios to choose the best possible solution to the problem.

An intuitive thinker, on the other hand, goes with his gut. Many researchers believe this type of thinking sparks creativity because it integrates so many different pieces of experience.

To explore what happens when one type of thinker follows a different approach, Dane and his fellow research colleagues gave test subjects a scenario. How could they get more students to come into a gift shop? Participants first had to come up with ideas using either an intuitive or a rational problem-solving approach. Then they filled out a short questionnaire. Afterward, the professors evaluated the ideas as creative or not creative, based on originality and usefulness.

When a participant wasn’t used to rational thinking and had to problem-solve using a more rational approach, he or she came up with more creative ideas, the researchers found. This, the researchers said, suggests it’s worth encouraging intuitive thinkers to change up their problem-solving style to come up with new ideas.

Curiously, it’s relatively easy to influence a person’s cognitive approach to a problem, the researchers found. At the same time, the research didn’t suggest that either approach — rational or intuitive thinking — was inherently better than the other. In fact, they wrote, future research on the topic ought to analyze what happens when subjects are encouraged to take a hybrid rational-intuitive approach.

In the meantime, whether you’re trying to lure customers to your new coffee shop, or figuring out the best ending to your crime novel, try attacking the problem with the thinking style that’s least familiar to you. To truly think outside the box, the first thing to do is peer over the side to see what style of thinking most often boxes you in.

Erik Dane is a former professor and was the distinguished associate professor of management (Organizational Behavior) at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Dane, E., Baer, M., Pratt, M. G., & Oldham, G. R. (2011). Rational Versus Intuitive Problem Solving: How thinking ‘off the beaten path’ can stimulate creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5(1), 3-12.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Men In The Mirror

Do the Latino boxers in a border gym know something other men don’t?

By Mary Lee Grant

Do The Latino Boxers In A Border Gym Know Something Other Men Don’t?

I am punching the bags at the Kingsville Boxing Club in Deep South Texas, the only Anglo and the only woman in the gym. It is a place of aspiration, a mix of professional boxers who make between $2,000 and $10,000 a fight, amateurs hoping to enter the big leagues and guys who drop by after work to punch the bags. Outside, the heat index is 107. Inside this abandoned tortilla factory with only two narrow windows and no air conditioning, it feels much hotter. Sweat drips into my eyes as I hit the heavy black bags with plastic Everlast gloves, slick with perspiration. The deep voice of salsa singer Celia Cruz resonates from crackly speakers though the cavernous old building.

The tattooed, muscled chests of the men moving next to me gleam as they grunt and grimace with every punch. Sweat gathers on the floor in pools that the boxers take turns mopping up. A sign reminds us: “Don’t spit on the floor.”

I have been practicing boxing at this mainly Mexican-American gym for two hours every day for the past year. Along the way, I have become close to men from both sides of the border, men who are boxing their way to a future they hope will bring them money and fame.

Mexican men may be the most maligned denizens of Trump’s America. Yet as I found myself growing ever more intimate with this group of macho athletes, I noticed qualities in them that the white men who are so quick to criticize might envy.

Watching them flex before the mirror, one throwing a glittery rosary around a neck, another perching a baseball cap at a studied sideways angle, I am reminded of the visual poverty that dominates the lives of most white men I know. I should point out that I am white and love many white men, so this is said with no ire. It is simply an observation, the musings of a woman who grew up as a minority in South Texas and watches with interest the differences between my own Anglo culture and the predominantly Mexican-American culture that formed me.

Unlike these vatos, white American men find few chances to relish their masculine beauty. Much ink has been spent on the rage of white men — school shooters, incels, suicides. Could white men be so angry in part because our society does not allow them the full expression of their masculinity?

We live in a society that says macho is toxic; some of its manifestations are so, profoundly. But perhaps our rules for masculinity are too limited. The result is a culturally enforced lack of style, panache and even physical grace, relentlessly mocked in popular culture from movies like “White Men Can’t Jump,” to country music, with songs like “If Bubba Can Dance, I Can Too,” and “Barney Jekyll & Bubba Hyde.”

Here at this border gym, I see something very different. I spend much of my time with men whose focus is the brute display of masculine power, who feel it is their calling to be warriors. And the anger and resentment against women that so often rears its head in the white professional world is absent here. Perhaps this arises in part because in the traditionally masculine fields in which many of them work — refineries, construction — women offer little competition. Unlike incels, who insist women must have the bodies of virginal 12-year-olds, these men enjoy women in their infinite variety. If the men at this gym have a problem with women, it is not that they hold them to impossible standards, but that they find too many of us attractive. I can’t help but wonder if their openness towards female beauty springs in part from embracing their own.

I am curious about what white men, constrained still by old Puritan ideals about excess and adornment in dress, might learn from Latino men, who come from a different strain of men’s style, one informed by the breezes of the Mediterranean. It is a sensibility shared by other men with cultures rooted in southern Europe, perhaps most flamboyantly Cretans, with their bandoliers, chapeaus, and styled moustaches. Perhaps if white men incorporated a bit of Latino style into their look, swag could become an everyday affair rather than an anomaly, a glass of wine with dinner instead of a drunken binge.

I see this style in the pride these boxers take in their bodies as well as their clothes. These are men who work out nine hours a day, jumping rope for an hour, running five miles twice a day, doing 100 sit-ups and a hundred pushups each day. And at a time when obesity rates are increasing among Americans, research has shown that overweight men face far more discrimination than those who aren’t obese.

In a study by Rice Business professor Mikki Hebl, overweight men were more likely to face casual discrimination than leaner men, both when shopping, and when serving as clerks at retail outlets. While past research has focused more on women and weight, it turns out that obesity affects how men are treated too.

“There is no doubt that I have self-confidence,” pro boxer Anthony Navarro told me. Like all professional boxers, Navarro watches his weight carefully so he doesn’t have to jump up to a higher weight class and fight bigger guys. He even sweats off final pounds in a sauna so he can make weight before a big bout. Navarro combines this body consciousness with a styled casual look, distinguished by bald head, tattooed backward baseball cap, white shirt, baggy jeans and Gangsta Nikes.

“Sometimes I see a really preppy white guy and I think, ‘That looks good. I could wear that,’” Navarro said. “But I notice they don’t wear as much jewelry and I really enjoy my jewelry. I got my ears pierced really young, just like my father. I wear gold chains. I have a black and silver rosary I really like. Sometimes, I wear it into the ring.”

The world of Latino boxing is one of grit, flash and corazon, or heart. Each boxer has a boxing persona, often correlating with his ethnic identity or nationality. One may walk out to fight in a sequined sombrero, another in Mexican flag shorts, accompanied by traditional Mexican tunes like Vicente Fernandez’s “El Palenque."

Their ring names exemplify hyped-up masculinity. I know three different men with rooster names: El Gallo Negro, El Gallo Giro, and El Gallo Fino. For all of them, the glitz and toughness of the boxing world carry over into their daily style. Outside the gym, for example, boxer “Toro” Herrera De La Paz sports a variety of looks, from fancy suit with green tie and matching green vest, to a sleeveless Lakers shirt showing his toned, arms paired with a blue and white rosary and blue and white cap. “I think it is all about having brown pride on you,” De La Paz said.

And while white men complain of feeling oppressed and aggrieved by American society, these men, who work as custodians, nursing home aides and ditch diggers, look at their own reflection with pride. In the tradition of Charles Atlas, transforming himself from a scrawny weakling into a muscle man, they stand with confidence, despite — maybe inspired by — having sand constantly kicked in their face by the dominant society.

A big part of this style, several boxers told me, is not physical prowess but attitude. “My grandmother always told me I have too much pride, because I don’t back down, but I think that is also part of the way you carry yourself,” said “Baby Jesus” Moreno who works out occasionally at the gym. “My main advice to white men is to relax. They don’t seem to feel at ease with themselves. You know, comfortable in their own skins. Also they might consider more bling.”

With all the talk of style, it may seem strange that carrying a baby is considered an excellent look by these men. But children play a key role at this boxing gym, crawling in and out of the ring, hanging on the ropes and watching their dads spar. Professional boxer Omar Rojas said he has been taking his son into the ring since he began to crawl, keeping an eye on him while he practices. Little girls in pink dresses with bows in their hair run between the punching bags, occasionally pounding them alongside the toughest of men. I have often seen these guys, with their hands wrapped, ready to put on boxing gloves, carrying a toddler out of harm’s way.

This comfort with the presence of children is not, of course, exclusive to Latino culture. But Latino tradition may encourage it. Navarro said his love of kids in no way counteracts his tough image. “If anything, I am more macho with a child in my arms,” he said. “Having children changed my life and turned me away from the streets. The most important thing for me is to be a role model to the little ones, both my own children and others. Plus, you know if they are here at the gym with us, they aren’t getting into trouble.” (Journalist Claudia Kolker addresses children in public life in the Latin American plaza in her book, The Immigrant Advantage: What We Can Learn from Newcomers to America about Health, Happiness and Hope.)

Spending much of my life as a journalist on the border, I have observed the daily horrors of machismo as I compiled the police blotter in hardscrabble towns whose names no one north of Corpus Christi would recognize. “Subject threw multiple unopened cans of Bud Light at female victim's face, then pushed her backward off porch. Subject said he was acting in self-defense. Victim transported to hospital. Victim chose not to press charges at this time.” It is no accident that many Latinas prefer to date and marry white men. Yet these boxers have shown me another side of Mexican masculinity. On these arid South Texas plains, I see displayed valor and dreams of glory worthy of a Cervantes hero.

And although a recommendation of “more bling” might seem a superficial solution to the existential crisis some white men face, perhaps the seemingly superficial can act transformatively. Actions seem to follow feeling, William James famously wrote, but actually the two are intertwined. “By regulating the action, which is under the direct control of the will, we can indirectly regulate the feeling, which is not. Thus the sovereign path to cheerfulness, if our cheerfulness be lost, is to sit up cheerfully and to act and speak as if cheerfulness were already there.”

Or as 12-step programs would have it, “fake it 'til you make it.” Maybe white men can imitate Latino style until they internalize it. Then Mexican macho swag will become as American as fajitas and breakfast tacos.

Mary Lee Grant has a degree in history from Yale University and a PhD from Texas A&M University, specializing in Mexican-American history and gender history.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Can We Ever Agree on What Corporate Responsibility Means?

A new theory offers a practical way to evaluate corporate behavior worldwide.

Based on research by Duane Windsor

Windsor’s vision for consistent corporate social responsibility wouldn’t require strict regulations carved into stone tablets. Instead, he argues, participants need to strike a balance between high ethical standards and the freedom for companies to grow — and allow room for standards to evolve over time.

Key findings:

- Clearer concepts of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility would make it easier to measure whether companies are meeting ethical standards.

- Establishing a reliable method of evaluating corporate social responsibility could lead to more consistent business practices worldwide.

- Crafting a new approach that’s both theoretical and practical could pave the way for improving corporate responsibility worldwide.

What’s the definition of a fair wage? What obligation do corporations have to protect the environment — or to maintain human rights? The answer depends on who you ask.

Corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility are nettlesome, ambiguous concepts — and nearly impossible to enforce. The literature about both currently spans several disciplines, forming a patchwork of principles. And this theoretical chaos poses a serious practical problem, both for corporations and for the countries where they do business. Consumers may suffer most of all.

But what if someone devised a formula for evaluating good business practices — one that could pave the way for consistency in corporate social responsibility across the globe?

Rice Business professor Duane Windsor resolved to try. In a recent paper, he tapped institutional theory, international policy regime theory, stakeholder theory and theories of how firms operate. He brought them all together with one overarching assumption: that people all over the world want better lives for themselves and their families.

To understand what role corporations could — and should — play in helping to maintain and improve the lives of stakeholders (and non-stakeholders), Windsor looked at the way theory and experience influence each other in the workplace. Secondly, he analyzed the ways persuasion and negotiation can encourage social responsibility and still allow for progress. This could involve UN and EU sponsorships that directly address such corporate policy issues as fighting corruption, promoting environmental protection, supporting human rights and developing and maintaining industry standards.

Pairing logical analysis with a review of the literature, Windsor articulated 19 specific points that could be tested, such as a firm’s performance outcome, the well-being of shareholders and non-shareholders and overall social welfare in the communities that corporations serve.

Since corporate social responsibility is currently evaluated across a variety of disciplines, specific conceptual boundaries could make good practices easier to identify — and to enforce. A consistent set of guidelines would also shape legal and ethical standards for public policy and business practices.

But these boundaries can only be created through a consensus between nations and corporations. And that can only take place with steady scholarship, persuasion and negotiation, Windsor says.

Windsor’s vision for consistent corporate social responsibility wouldn’t require strict regulations carved into stone tablets. Instead, he argues, participants need to strike a balance between high ethical standards and the freedom for companies to grow — and allow room for standards to evolve over time. This is crucial, he says, since lasting success depends on balancing corporate social responsibility and an environment where companies can flourish and succeed.

An international standard of corporate responsibility would not only help businesses interact better with each other and the governments that oversee them, but, ideally, would increase transparency and improve quality of life around the world.

A consistent framework alone won’t make this happen — it will also take a commitment to meaningful enforcement by company leaders and government officials. But it would help if they could all start out on the same page.

Windsor, D. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Irresponsibility: A Positive Theory Approach.” Journal of Business Research 66 (2013): 1937–1944.

Washington Campus Board of Directors

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Here’s How to Encourage Creativity in Your Team

Companies can and should train supervisors to cultivate creativity in their management choices. Here's how.

Based on research by Jing Zhou and Inga J. Hoever

Choosing and hiring employees who are creative is not enough, it turns out. If your workplace is discouraging, creativity will wither in almost anyone. On the brighter side, cultivate a nurturing environment and creative tendrils may sprout even in the most no-nonsense workers.

Key findings:

- Creativity is the lifeblood of modern business — the spark behind innovative ideas.

- Today’s managers have a mandate to cultivate creativity in their workforce.

- Managers can nurture creativity, even in workers who appear less creative, by building a supportive environment.

Give a kid a toy car, a stuffed bear, or an armful of blocks, and she is off on an imaginative romp, staging epic battles, building palaces or creating new worlds.

Coaxing creativity from adults is more challenging. But if creativity in children develops their spirits, creativity in adults enriches productivity — especially at the office.

It’s simple math. Creativity is where ideas come from; ideas form the basis for innovation. In an increasingly competitive world economy, it’s innovation that allows businesses to survive and thrive. This makes creativity a prized commodity in the job market. For managers, cultivating creativity in their workforce is a crucial professional skill.

Identifying the best circumstances to make creativity bloom is one of the driving questions in a study by Rice Business Professor Jing Zhou and colleague Inga J. Hoever, a professor at the Barcelona School of Management in Spain.

To explore the mystery of creativity, the two scholars first reviewed the hefty body of research by organizational psychologists and management scholars who’ve studied innovation in employees and teams. Most early research in this field, published since 2000, focused on the creativity of the actor — the individual or the team — or else revolved around the work environment.

Current academic research takes a more holistic look. By studying the interaction between the character traits of the worker or the team, the leader or the supervisor, and the prevailing atmosphere at the workplace, researchers are unveiling new insights.

Studies show, for example, that the benefits of benevolent leadership expand when workers recognize creativity as an important component of their role. Not only that, creativity is highest in employees who experience high levels of both positive and negative moods and feel supported by their supervisors. Other research finds that leaders who empower their workers get a greater payback in creativity.

To explore these findings further, Zhou and Hoever developed a typology that sorts out research about workplace creativity based on interactions between the worker (which they call the “actor”) and the workplace (which they call “context”).

The best-case scenario is a positive actor in a positive context, a mix that is synergistic for creativity. Worst case: When a positive actor languishes in a negative context or, similarly, when a negative actor stews in a positive context. At the extreme end of possibility, a negative actor in a negative context is downright antagonistic to creativity, Zhou and Hoever found.

There’s one final type of employee-workplace interaction: the “configurational” experience, which includes factors that are neutral in shaping creativity, but, when combined with other factors, cause a kind of chemical reaction that boosts or blocks creativity.

Zhou’s research serves up some bad news and good news for managers. Choosing and hiring employees who are creative is not enough, it turns out. If your workplace is discouraging, creativity will wither in almost anyone. On the brighter side, cultivate a nurturing environment and creative tendrils may sprout even in the most no-nonsense workers. Best of all, good managers can build a nurturing greenhouse environment. Practically speaking, it means that companies can and should train supervisors to cultivate creativity in their management choices.

Plenty of research gaps remain, however. To fill them, Zhou has outlined an ambitious agenda for future research, including a close look at the impact of workplaces on collective creativity; exploring as-yet unidentified factors in workers and work settings that spark creative thinking; and seeking ways to vanquish the effects of unsupportive environments.

Making creativity happen at work, in other words, isn’t child’s play.

Zhou, Jing, and Hoever, Inga J. “Research on Workplace Creativity: A Review and Redirection.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1 (2014): 333-59.

Mary Gibbs Jones Professor of Management and Psychology – Organizational Behavior

Never Miss A Story