Study Guide

Innovation is the engine of business. But how much do researchers really know about it?

Based on research by Jing Zhou, Neil Anderson and Kristina Potočnik

Innovation Is The Engine Of Business. But How Much Do Researchers Really Know About It?

- Current research in workplace innovation and creativity needs comprehensive review to determine what elements are lacking.

- Researchers can benefit from a framework that can structure future inquiry.

- Despite shortcomings, research in innovation and creativity is essential to helping organizations stay relevant.

Innovation and creativity are crucial tools that all businesses need in order to prosper. Research into how these tools work covers a broad area and crosses various disciplines. In the past, much of this research has been divided: One side looked at innovation, which focuses on how ideas are implemented, while the other examined creativity, which focuses on coming up with new ideas. Rice Business Professor Jing Zhou and colleagues addressed this divide by reviewing research going back a little more than a decade, looking for key measures that could be used as guidelines for future research.

Zhou and her colleagues began their work by reviewing the practical and theoretical perspectives of innovation and creativity in the workplace. They then created a framework for future research after identifying prominent theories.

Before getting started, however, they needed clear definitions for both innovation and creativity. Creativity, Zhou proposed, centers on idea generation. It’s the first step toward innovation. Innovation, she concluded, stresses the implementation of ideas. This happens at different levels: individual, team, organization, or across multiple levels.

At the team level of innovation, research has progressed significantly, the authors found. They suggest that researchers now focus on other aspects of team-level research, such as team environment, leadership and facilitators of workgroups.

At the organizational level, Zhou and her colleagues found that numerous studies looked at the factors that influence innovation. But, they concluded, there’s still very little conceptual explanation for how individual creative attempts become organizational innovation.

The team’s review reveals the enormous strides that researchers have made in the field of creativity and innovation in recent years, and clarifies how their studies have been used by different organizations.

Despite advances in the field, however, there are still shortcomings. Many studies, for example, are hampered by problematic research approaches. Some lack theoretical groundwork and few take an inclusive approach to multi-level studies.

Zhou and her colleagues argue that addressing these limitations would be a tremendous leap forward in understanding creativity and innovation in the workplace. Without innovation, companies can’t prosper and progress. The same holds true for academic research into these lifelines of business success: It will need to expand and dig deeper or cease to be relevant in practice.

Jing Zhou is the Mary Gibbs Jones Professor of Management and Psychology in Organizational Behavior at the Jones Graduate School of Business of Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and Creativity in Organizations: A State-of-theScience Review and Prospective Commentary. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297-1333.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Careful Ascent

How to raise prices without driving away customers.

By Vikas Mittal

How To Raise Prices Without Driving Away Customers

Many managers believe that the only way to get customers to pay more is to load their products and services with more and more features.

This is the classic value trap — provide more benefits to extract higher prices. Another approach — cost-plus pricing — relies on providing customers with justifications for price increases; justifications such as increased labor costs, inflation and higher raw-material costs.

Price increases, done incorrectly, often result in customer dissatisfaction and brand switching. It’s no wonder raising prices is a stressful, contentious and unpleasant process. When harried, some firms avoid raising prices by taking “self-harming” measures, such as reducing head count, lowering product quality and reducing services.

Such drastic actions may not always be necessary. Research on consumer reaction to pricing has identified several factors that can help firms to decrease customer price sensitivity. Reducing price sensitivity can enable firms to raise prices without negative side effects.

Four Levers for Raising Prices

1. Time your increases wisely.

Several studies have examined customer price sensitivity relative to economic cycles. The main result of a major study in the U.K. was that long-term price sensitivity of customers tends to decrease during economic expansions. Customers are more price-sensitive during economic contractions. These results have also been documented in a meta-analysis, where researchers summarized results of 81 different studies. While this may seem intuitive, firms often fail to take advantage of economic cycles to manage their pricing strategy. Firms may be more prone to give price cuts during recessionary periods to retain or gain customers, they should also recognize decreased long-term price sensitivity during expansion periods.

Especially in cyclical industries, such as oil and gas, firms should implement price increases during economic expansions. During these times, firms may want to tilt their focus toward managing customer value through non-price mechanisms. Lowering prices to retain or gain share may only train customers to become more price-sensitive. The costs and benefits of such a strategy should be carefully evaluated.

2. Focus on customer satisfaction.

In a classic study based on the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ASCI), the research team examined five years of data from several firms to determine the association between overall customer satisfaction and customers’ willingness to tolerate a price increase. Results showed that an increase in overall customer satisfaction decreased price sensitivity: “A 1% increase in customer satisfaction should be associated with a 0.60% decrease in price sensitivity.” Interestingly, the study also found an effect of competitiveness, as measured by industry concentration. It found highly satisfied customers of companies operating in highly competitive markets are less likely to tolerate a price increase. Identify customers who are highly satisfied, because they should be relatively more receptive to a price increase. If you decide to increase prices, do it in a way that analyzes and accounts for potential competitor responses. If you are in a market with many competitors, proceed with caution.

3. Build brand equity through advertising.

We all understand the difference between advertising and promotion. Advertising is communication designed to build unique, positive and strong associations with a brand in the minds of your customers. Promotions — discounts and giveaways — stimulate purchase behavior.

A long-term study of grocery store buyers showed that advertising helped build brand equity, customer loyalty and repeat brand purchases. In contrast, promotions prodded customers to become progressively more price-sensitive, harming long-term profitability. This is also consistent with another result: Price sensitivity for generic brands is typically higher than national brands, presumably because the latter have higher brand equity than the former.

Manage pricing strategy in conjunction with your advertising and promotion strategy. In many firms, especially B-to-B firms, pricing may be determined by the sales function while advertising is run by the communications group. Close cooperation between the two groups can be beneficial.

4. Tap into customers’ local identity.

A forthcoming paper in the Journal of Marketing showed that consumers with a stronger local identity are willing to pay more for products because of a sacrifice mindset. Once activated, a sacrifice mindset leads to lower price sensitivity, regardless of the origin of the products under consideration. As an example, management at a grocery store communicated with half its customers to activate their local identity. Then it raised prices for organic eggs, rice and milk. Results from this field experiment on actual purchase behavior showed that purchase quantities were less sensitive to price increases for the local identity group than for the global identity group.

Firms can use simple communication materials to prime a local identity among their customer base to decrease their price sensitivity. Global companies can execute these strategies without resorting to the costly approach of localizing production or positioning the company as having local roots.

Raising prices can be difficult. By linking price increases only to increased product performance, more features and higher value, firms may set themselves up for a vicious spiral of higher costs and higher prices. This can lead to feature fatigue, which can confuse and irritate customers. Raising costs can also erode long-term competitiveness.

Moreover, such an approach takes a very mechanistic and cognitive view of the customer. By expanding and linking their pricing tool kit to brand equity, customer satisfaction, customer identity and market factors, firms can view customers as complete human beings. These factors, when integrated into your pricing strategy, can build a longer-term approach to managing and mastering price increases.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Management in Marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

This article first appeared American Marketing Association's Marketing News as Customer-Based Strategies For Raising Prices.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

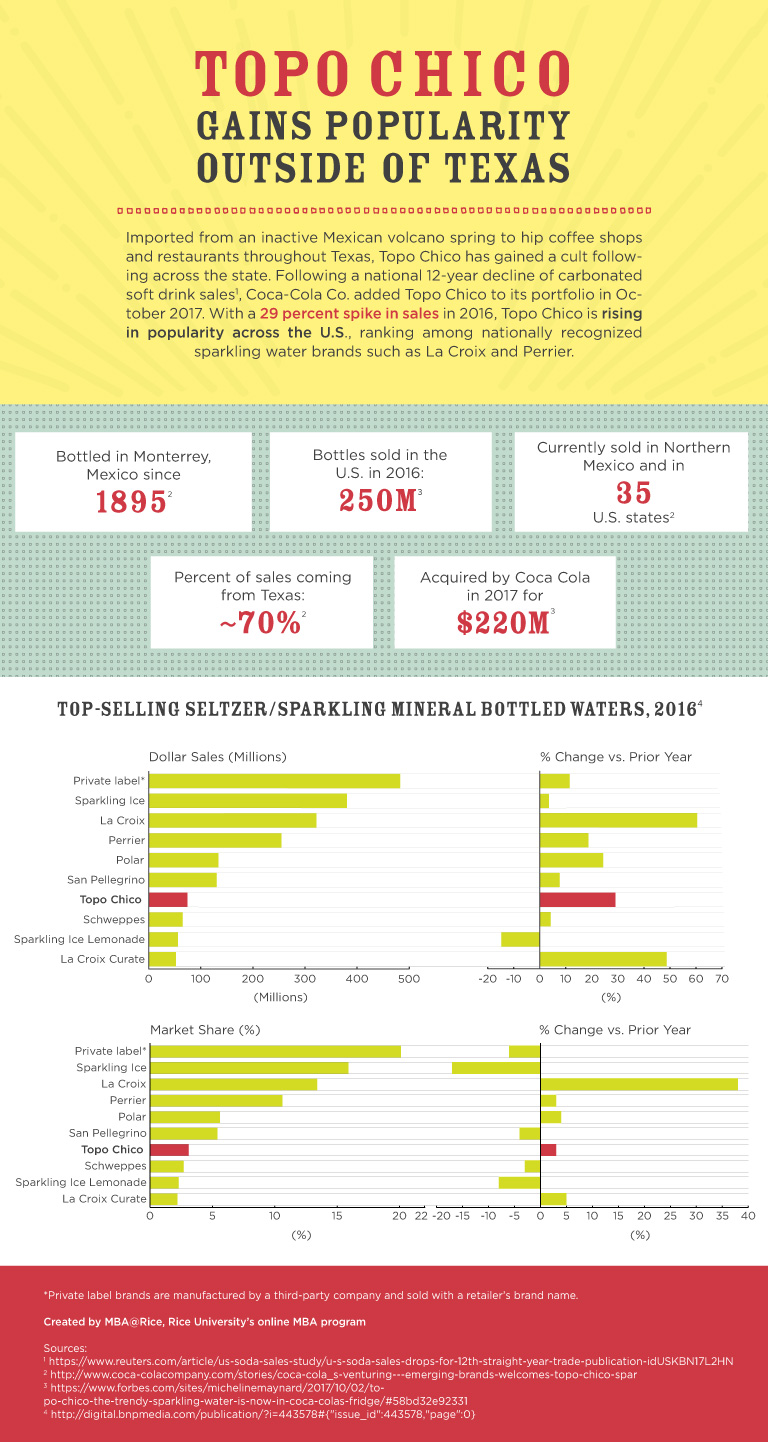

Pop Culture

Why there's still potential in products that have lost their fizz.

Why There's Still Potential In Products That Have Lost Their Fizz

James Quincey, head of the Coca-Cola Co., was being grilled about Diet Coke.

The chief executive of the world’s largest soda company – its market capitalization is about $188 billion – was on an earnings call with analysts anxious to know what he was doing to save the iconic brand. Quincey had been talking up his massive firm’s bright future in its wide range of products, but then a question came up about plans to revive Diet Coke, sales of which had been in decline for years, losing out to non-soda competitors such as LaCroix and San Pellegrino.

“What’s the picture of success?” an analyst asked. Would the new plan just stanch the bleeding? Or could the legendary brand actually grow again?

Panic about Diet Coke’s fate has weighed on Coca-Cola’s stock price and given birth to hundreds of articles about the company’s “flat” earnings. But the truth is there’s opportunity in decline. In fact, some companies manage to increase profits even as sales drop. It’s a concept so counter to typical business thinking that the phenomenon is often overlooked.

“If your industry is shrinking, it’s tempting to spend money to get new customers,” says Rice Business marketing professor Amit Pazgal, who has studied increasing profits in declining markets. “But that can be expensive. It’s much better to spend on the customers you have left.”

Those faithful few can prove lucrative. Pazgal points to the cigarette industry as a powerful example. Its companies found ways to raise prices on their most loyal — and yes, addicted — consumers even as demand declined. When states started slapping new sin taxes on cigarettes, the tobacco companies added a little more to the price. Their least loyal, and likely most price-sensitive, customers had already quit the habit. That meant the companies were left with their best customers, many of them willing to pay more.

Not all declines, however, are ripe for reaping increased profits. According to Pazgal, demand needs to trail off. It can’t just plummet. The customer base needs a substantial number of loyalists who will stick with the brand through hard times. That way a business can steadily increase prices to the right consumers, even if there are fewer of them.

Diet Coke, as it turns out, has plenty of loyalists — people who turn down a Diet Pepsi at a restaurant or get grumpy when their home supply of Diet Coke runs low. One of the most famous Diet Coke fans is President Donald Trump, who reportedly downs 12 cans a day. People magazine has written about the drink’s “strangely dedicated fan base,” and the motto “My favorite color is Diet Coke,” has made its way onto T-shirts.

Such loyalists have helped keep Diet Coke one of the best-selling brands in the nation, even as soda consumption has fallen to its lowest level in three decades, and sales of calorie-free and unsweetened fizzy waters have doubled. Coca-Cola is clearly adapting to customer preferences by diversifying its portfolio with product acquisitions like the trending sparkling water brand Topo Chico.

In his call with analysts, Coca-Cola boss Quincey sounded enthusiastic about the potential of new Diet Coke flavors. The descriptive names — twisted mango, feisty cherry, zesty blood orange — were a clear bid to lure younger buyers. Yet the new offerings could also misfire with core Diet Coke drinkers who love their soda just as it is.

Understanding what keeps people hooked is key, says Christian Goy, cofounder and managing director of Behaviorial Science Lab in Austin, Texas, which provides companies such as Coca-Cola insights into customers’ priorities.

“For loyal customers, what we can see and measure is how expectations are fulfilled and why,” Goy says. “What we’ve found is that sometimes a product fulfills one or two expectations very well. That’s the hook the company needs to play up to continue to be paramount in their minds.”

A declining market can be freeing for a company. It doesn’t have to pander to consumers who aren’t connected to the brand, the kind who will switch allegiances at the drop of a coupon. That’s one reason, research shows, that knockoffs of high-end luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton handbags are not necessarily harmful to a company: The fakes weed out consumers who are most motivated by price.

Few companies, though, have the discipline to keep from chasing those price-sensitive buyers. That helps put downward pressure on prices, but it also means forgoing profits from loyal customers who wouldn’t mind paying a little bit more for a luxury handbag.

Pazgal suspects the same is true for Diet Coke. While most businesses shudder at the prospect of managing a product’s long decline, Pazgal suggests, the journey itself can prove a worthy ride.

“Think before you leave,” he says. “Because it might still be profitable for another 20 years."

Citation for this content: MBA@Rice, Rice University’s online MBA program.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Up, Up And Away

How living abroad can clarify your sense of self.

Based on research by Hajo Adam (former Rice Business professor), Otilia Obodaru (former Rice Business professor), Jackson G. Lu, William W. Maddux and Adam D. Galinksy

How Living Abroad Can Clarify Your Sense Of Self

- New research shows that foreign travel helps to strengthen our idea of ourselves – a notion called “self-concept clarity.”

- Living abroad helps build a clearer sense of self because it inspires us to better understand the differences between who we are and who we were taught to be.

- It’s not the number of countries visited, but the amount of time spent abroad that builds self-clarity. The longer the time in another country, the clearer the sense of self.

Imagine yourself on a singular adventure in a foreign country. The mere thought of it inspires a certain vitality: From Moses to Odysseus to Alexander the Great, leaders have traversed the horizon in order to become their true selves.

Researchers have already documented how foreign experiences fire creativity, shrink prejudice and accelerate career success. But these studies are the embarkation point of a larger effort tracing the psychological ramifications of travel abroad. That research suggests we’re just beginning to learn how formative living in another country can be.

In a recent study, former Rice Business professors Hajo Adam and Otilia Obodaru studied the role of experience abroad upon “self-concept clarity” — our inner concepts of ourselves. Living abroad, they hypothesized, boosts self-concept clarity because it challenges us to understand who we are — as opposed to who we were raised to become. The researchers believe that it isn’t how many countries one visits that prompts such reflection, but rather the intensity and length of time spent beyond borders.

Why should any of this matter when it comes to business? Extensive research already links self-concept clarity to an array of positive outcomes from well-being to physical health. Moreover, Adam and Obodaru show that a strong sense of who you are and what you want also represents the kind of thinking critical to making smart decisions regarding career choices. Foreign travel, they posit, builds the clarity necessary to know what we really want out of our working lives.

To test their theory, Adam and Obodaru joined Adam G. Galisnsky of Columbia Business School, Jackson G. Lu of MIT's Sloan School of Management and William W. Maddux of the University of North Carolina's Kenan-Flagler Business School to conduct six studies involving 1,874 people, among them MBA students from various countries and participants online. The intricate investigation went through a series of different phases.

First, the researchers explored whether people who had lived abroad reported higher self-concept clarity than individuals who had not lived abroad. In addition, they examined if self-concept clarity was stronger for people who had lived abroad was stronger than for those who simply wanted to but had not yet done so.

The research wasn’t limited to how the respondents saw themselves. Using a 360-degree rating system, the scholars compared the respondents’ self-image with their colleagues’ descriptions of them. Finally, the researchers studied whether deep and broad living experiences abroad were in fact an indictor of clearer decision-making capacity.

In virtually every study, the results echoed each other. Experience abroad increased the respondents’ self-concept clarity. This effect was not transitory, but shaped how the respondents constructed their identity over a period of time.

Even on the best of adventures, experience in a new culture can be stressful. Yet the research shows that the challenge of living abroad offers powerful benefits. In contrast to the stress associated with disruptive experiences like losing one’s job or getting divorced, the researchers found that spending time abroad had a lasting positive value for a clear sense of self.

So the next time you plan a venture abroad — whether it’s a year in Paris or a prolonged work stint over the border — consider that your experience may not just be an adventure. It may mean more clarity about yourself and your next job.

Hajo Adam and Otilia Obodaru are former assistant professors of management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

For more information please see: Adam, H., Obodaru, O., Lu, J. G., Maddux, W. W., & Galinksy, A. D. (2018). The shortest path to oneself leads around the world: Living abroad increases self-concept clarity. Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 145, 16-29.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Like Minded

Like customers, donors can be segmented by a variety of drivers.

By Vikas Mittal

Like Customers, Donors Can Be Segmented By A Variety Of Drivers

A Charity Navigator report showed an estimated $373 billion was given to charitable causes in the U.S. in 2015, with 71% of donations coming from individuals. Individuals donate to a variety of nonprofit causes such as religion (33%), education (16%), human services (12%), health (8%) and public-society benefits (7%).

Melinda Gates, a pioneer of the Giving Pledge initiative, argues: “Philanthropy is different around the world, but almost every culture has a long-standing tradition of giving back.” This statement suggests that people donate not just to give back, but to fulfill multiple motivations. Nonprofits can address five specific motivations to encourage donor engagement.

1. Moral Identity

Formalized in 2002, moral identity is the extent to which the idea of being moral is important to a person’s self-concept.

A 2009 study examined differences between men and women donating to victims of Hurricane Katrina or victims of terrorism in the U.S. or Middle East. The study found that men, in general, are less likely to donate than women. However, as the importance of moral identity increased, donation behavior increased among both males and females.

Scores of studies with many samples of customers in different donation contexts and for a variety of nonprofits show the same conclusion: Donors who place a higher importance on moral identity also donate more.

In addition to identifying current and potential donors who score high on moral identity through a survey, nonprofits can use simple communication strategies to activate the importance of moral identity among donors. Both of these approaches can enable charities to focus on donors with the highest giving potential.

2. Recognition

Donor recognition is a cornerstone of fundraising. Nonprofits recognize donors in newsletters, on websites, by engraving their names on building facades, using ribbons pinned to donors’ jackets and sending them thank-you notes. Yet, donor recognition does not motivate all donors. Recognition may increase donations among donors who are symbolizers, but not among internalizers.

Internalizers feel fulfilled by acknowledging the importance of donation to their own self; they do not need any social verification of the importance of donating. Symbolizers, on the other hand, feel fulfilled when others acknowledge their donation; social verification is crucial for symbolizers. As such, internalizers are uninfluenced by recognition, whereas symbolizers cherish it. The moral-identity scale mentioned earlier can be used to identify symbolizers.

A 2013 study in the Journal of Marketing found that donation increased among symbolizers, but not among internalizers, when a nonprofit said the names of donors would be published on the charity’s website. Symbolizers also donated more when the nonprofit was willing to acknowledge the donation with a thank-you note.

Cost-effective recognition mechanisms can increase donations among symbolizers in a nonprofit’s donor base. Low-cost recognition strategies that are effective include listing donor names on a website, sending thank-you notes and utilizing online tools and social media such as Facebook, Twitter or LinkedIn.

3. Time Versus Money

Is donating time the same as donating money? Are time and money interchangeable means of donor engagement?

Research in the 2007 issue of the Journal of Marketing shows that donors who place a higher importance on moral identity prefer to donate time than money, even when the opportunity cost of time and money is the same. This happens for two reasons: First, donors may see the act of giving time as embodying the values of care, social responsibility and being heartfelt. Second, donors may view the act of giving time as more self-expressive and engaging than writing a check. This is especially true when time is donated amid multiple other donors and volunteers.

Donating time is more engaging and socially rewarding for donors than donating money. Nonprofits may start by asking donors to volunteer time. As engagement and self-expression increases, donors may be approached for monetary donations. Even when they give a lot of money, donors can feel more committed if they also give time.

4. Charity Positioning

Save the Children is a charity dedicated to helping children get a healthy start in life, an opportunity to learn and protection from harm. Such a charity should be equally attractive to all donors, but in a randomized study, respondents saw Save the Children either as a private charity or as a government-managed agency. Among those with high moral identity, Republicans were more likely to donate when the charity was positioned as a privately managed charity. In contrast, Democrats were more likely to donate when the charity was positioned as a government-managed agency.

Another study showed women were more likely to give to charities positioned as providing for other people—even strangers and distant others. In contrast, males were more likely to give to charities with a narrower focus.

No doubt, the overall mission of a nonprofit is critical to gain donor support. Equally important is aligning the charity’s positioning with the broader set of attitudes and values of its donor base. Are the donors generally more conservative or liberal? Do they care more about local or global causes? Understanding these values can be very useful in soliciting donations.

Identify issues that are important to donors, and align your nonprofit’s positioning and brand to be consistent with these issues and attitudes. This will require subtle changes in the messaging and positioning of a nonprofit, but it can go a long way in improving fundraising.

5. Social Media

When donors were asked to like a charity’s profile on social media, donations decreased among some who liked the charity on social media, compared to those who did not. Termed “slacktivism,” the phenomenon of liking a nonprofit on social media serves two purposes: It fulfills a desire to present a positive image to others and a desire to be consistent with one’s own values. More generally, it serves the dual purpose of internalizing and symbolizing. Intriguingly, after liking a charity on social media, donors donated time and money if they saw the engagement as being meaningful. Thus, social media engagement can be a useful way to prime donors, but only if donors find the subsequent engagement to be meaningful.

Nonprofits can strategically use social media to initiate engagement among their donors. Coupling this with meaningful activities can help donors align their values with the nonprofit’s cause and feel more connected to it. Nonprofits should use social media as part of a larger plan to meaningfully engage donors.

Engage Donors by Treating Them as Customers

Successful organizations long ago realized the complexity of customer needs; the same goes for donor needs. Identifying patrons with a strong sense of moral identity and understanding, whether they are internalizers or symbolizers is a key step for engaging them. Once donors are engaged, nonprofits can manage the engagement process in terms of donor time, money and social media presence.

Finally, the nonprofit’s mission, while crucial, may not be the sole driver of donor engagement. Subtle tweaks to how the mission is communicated to donors can garner strong donor engagement. Insights to address these issues can be easily obtained via surveys and in-depth conversations with donors.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Management in Marketing at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice Univeristy.

This article first appeared American Marketing Association's Marketing News as 5 Ways Nonprofits Can Engage Donors.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Positive Feedback

Companies can earn more by deriving insights and informing strategies with customer feedback.

By Vikas Mittal

Companies Can Earn More By Deriving Insights And Informing Strategies With Customer Feedback

Customer satisfaction is a major predictor of a firm’s financial health. Companies try to measure and improve customer satisfaction using customer surveys. Research shows many companies use a short, 2-5 item survey to document their overall customer-satisfaction rates. Typically, such a company finds a high rate of overall customer satisfaction (90% or more customers indicate they are “satisfied”). Happy with it, management becomes complacent.

Despite high customer-satisfaction rates, companies that only measure overall satisfaction have a difficult time realizing its benefits. Many of these companies experience low customer retention, declining profitability, and low rates of customer acquisition. Why does this happen?

Is it the case that customer satisfaction is unrelated to retention or profitability? No. Rather, this happens because companies take a narrow view of customer satisfaction. They can substantially improve the ROI on the customer satisfaction research if they tap into its ROI drivers.

ROI driver # 1: Develop a customer-based model.

Instead of focusing only on overall satisfaction, a customer-based model also provides:

- Insights for an execution plan

- Key performance indicators related to strategy.

Perceived performance on key-driver attributes can increase overall satisfaction with the firm. Overall satisfaction is associated with customer loyalty—retention and referrals—which can drive revenues, market share, and profitability. The execution plan and KPMs should focus on key attributes linked with overall satisfaction.

Most firms only measure overall satisfaction. Some firms measure key attributes. Many firms fail to take appropriate measures of customer loyalty. Still others fail to link loyalty to revenues and profitability. To improve customer satisfaction ROI, a firm should simultaneously measure and statistically model all aspects of the customer model.

ROI driver # 2: Identify key driver attributes.

Identify specific attributes that are actionable. An attribute is specific and actionable when it can be objectively rated by customers and operationally implemented by the company. In a satisfaction study for a document delivery company, qualitative interviews showed reliable delivery to be a key driver. However, this was not specific enough. We drilled down to discover that reliable delivery really meant delivery within two days. In the satisfaction study, we included delivery within two days as the attribute. It was specific, measurable, and actionable. The firm made it a goal to make 99% of its deliveries in two or fewer days.

Second, all attributes are not equally important. We can determine relative attribute importance using multivariate statistical analysis that adjusts for the inter-relationship among attribute ratings. Simplistic techniques such as rank-ordering attributes based on average scores of a correlation coefficient can be misleading. They should be avoided.

When a firm does not identify key-driver attributes, its management ends up investing limited resources on more attributes than is necessary. A study of automotive customers showed that among the 30 attributes measured in the satisfaction survey, only five were key drivers of overall satisfaction. These included: roominess, accessories, handling, transmission, and brakes. Further research showed that interior roominess has specific dimensions such as: leg room, elbow space, and high ceiling. Similarly, a study for a national lawn-care company showed only punctual service and competitive pricing were key driver attributes.

A key driver analysis enabled management at each company to narrow its execution focus. This enabled it to improve overall satisfaction with fewer resources.

ROI driver # 3: Customize key drivers for different segments.

Different customer segments ascribe different levels of importance to an attribute. For example, a satisfaction study among airline customers showed quality of meals was equally important to all customers. However, comfort was eight times more important among business travelers who more frequently took long international trips. Similarly, in a study of computer programmers, attribute such as documentation was more important among new users, but reliability and capability were more important for expert users.

By incorporating segment-specific differences firms can better optimize performance on the attributes most important for their target segment(s). Learning: ascertain the target segments for your company and then conduct separate key-driver analysis for each segment.

ROI driver # 4: Time changes everything.

A study of mutual-fund customers showed trust and confidence in the advisor is very important in the early stages of the relationship. However, over time efficiency becomes the key driver of satisfaction. Similarly, a credit card company found that among new users, credit limit and interest rate are more important, but among customers who have been with the company for a long time additional services such as frequent user points were more important.

Strengthen relationships and overall satisfaction by focusing on those attributes that are most relevant at different times in a customer’s relationship. Statistically addressing these time-sensitive changes allows a company to use a dynamic approach toward its customers.

ROI driver # 5: Link customer satisfaction to customer loyalty.

A large body of academic research shows a positive association between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty metrics like retention, word-of-mouth, and referrals.

Yet, for different firms and industries this positive association can vary in magnitude. A study of automobile buyers found satisfaction had a stronger effect on repurchase behavior among males than females. Another study showed the association between patient retention and patient satisfaction differed based on patient income.

Firms also need to customize their loyalty metrics. For an automotive company it may be purchase or repurchase of its brand. For a telephone company it may be the number and duration of calls made, and the number of days/months that a consumer stays with the company. The appropriate retention metrics for a bank may include share of wallet, number of accounts, and the balance in each account. Unless retention measures are carefully aligned with a firm’s strategy, they may consume resources without being actionable or improving financial performance.

ROI driver # 6: Monetize customer satisfaction and customer loyalty.

Customer loyalty benefits a firm in many ways. Higher customer retention means a base of customers who buy more frequently, in greater volumes, are more prone to try other offerings by the firm (“cross-buying”), generally require lower maintenance, and become less sensitive to the outreach of competitors. All this should increase revenues while lowering the cost of marketing and sales through positive word-of-mouth by satisfied customers. Therefore, retained customers are a revenue-producing asset for the firm.

Customer acquisition costs determine the price of this revenue-producing asset. Customer acquisition costs may be lower for a company whose customers engage in positive word of mouth, recommend the company to others, and refer it to their colleagues.

Research shows a firm that simultaneously focuses on customer acquisition and customer retention can be more profitable than a firm that only focuses on one. As an example, consider a firm only focused on customer acquisition. The revenue-stream from a retained customer is lost to the firm when a customer leaves. The firm not only loses sales, but also the benefits of retained customers such as lower servicing and marketing costs. The loyal customer has to be replaced (at a high acquisition premium) by a new customer who initially buys less frequently and in smaller quantities (lower revenues), requires more service (higher service cost), and is less likely to recruit new customers (higher marketing costs). Smart firms link their customer satisfaction strategy to their customer-lifetime-value metrics. This ensures the firm can identify, acquire, and retain the most profitable customer segments.

ROI driver # 7: Shun spurious loyalty.

There is a growing trend focus on customer loyalty metrics such as customer referrals, customer recommendations, and customer acquisition. As the recent example of Wells Fargo shows, an exclusive focus on loyalty metrics can mislead executives and employees and even harm customers.

Customer loyalty must be earned through customer satisfaction, and not garnered via shortcuts such as high-pressure sales tactics, easy giveaways to lure customers, and price-based promotions. Firms should develop an integrated satisfaction and loyalty strategy to optimize overall revenues and profitability. In industries such as banking, business-to-business, and healthcare, many companies are already doing this.

These seven ROI drivers can help ensure your customer satisfaction and loyalty programs generate the anticipated ROI. To do this, your company will also need to customize its approach to its strategic goals and execution abilities. This customization can drastically reduce the incidence of costly mistakes and help firms maximize their ROI on customer satisfaction.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Management in Marketing at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice Univeristy.

This article first appeared American Marketing Association's Marketing News as Seven Ways To Maximize Your Company's Customer Satisfaction ROI.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

The Things They Carried

What does the last thing we grab in a disaster say about us?

By Claudia Kolker

What Does The Last Thing We Grab In Disaster Say About Us?

When push came to shove, Diane Sanchez went for the hedgehog.

Why a hedgehog? Why, as Houston reeled under Hurricane Harvey, and putrid water rose in the 47-year-old teacher's house, when it became clear she would soon lose the home where she'd lived for 13 years – why did Sanchez seize the family dog, sling a bag of clothes on her shoulder, and with her remaining free hand, grab Auggie the hedgehog?

Disasters open unexpected windows into who we are. The question of why, in extreme moments, we choose to save what we do has no single answer. Instead, after that first impulse to save loved ones, the last object chosen from a left-behind life can be a signal of what really matters.

Marketing plays a role, of course; infusing objects with meaning is the industry's sole purpose, notes Utpal Dholakia, a marketing professor at Rice Business. The more compelling the story, the more valuable an item will seem. Yet it's rarely marketing that determines the truest object of desire. Instead, deeper instincts – some universal, some utterly personal – make the decision for us.

Six months after Hurricane Harvey drove some 39,000 people out of their homes, the stories of what those Houstonians grabbed under duress can be instructive. Many survivors had time only to save themselves and the clothes on their backs. But others could save a bit more. In the chaotic moments before plowing into the water to safety, these Houstonians grabbed an oddball array of objects from their old lives.

The items they took – and those they left behind – reflected more than what was just possible, or even practical. They signaled who these Houstonians were, and what they felt they needed to survive.

Holed up on the third floor of his house in West Houston, Allen Wuescher heard chimes. He was, he thought, alone. The neighborhood was underwater, his wife Lucie and three small children were in Austin. rescuers had yet to arrive. All evening, as the water crept in, Wuescher had hauled valuables upstairs. The first floor went quickly. Now, the second story was gone too, and Wuescher waited on his final floor in the dark to be rescued.

It was just before firefighters shouted from outside that Wuescher figured out the chimes. A box of wine glasses was floating near the living room ceiling, clinking as though held by unseen partiers. By the time he called his wife to say he was fleeing, Wuescher was so rattled he just did what she said: He jammed a Disney "Frozen" backpack with small valuables, and then he stuffed a Minions mini-suitcase with avocados.

Avocados? Even though he was armed with credit cards, a cellphone and friends who could shelter him, Wuescher still believes the avocados were a good choice. "I had no idea where I was going," he says. That Minions bag of vegetables signaled he was never alone. "Lucie made sure I had food," he says. "It's good in that kind of situation to have someone think for you."

Clearly, external sustenance like food and family are essential. But emotional rescue can take other forms. Psychotherapist Rosalie Hyde, who specializes in trauma and works with Harvey survivors, notes that all people hold onto things that have meaning beyond the object themselves. These choices, she says, can be conscious or unconscious, and often complex, rooted in very early emotional attachments.

One flood survivor, for example, might save a jar of pennies because it reminds her of someone tender and nurturing. But another might grab an object reminding him of a positive moment with someone who was not otherwise kind.

For Sharon Bippus, an ESL teacher who fled her townhouse, the cherished object was a deck of cards. Soft-spoken and impish, Bippus can put the most anxious student at ease. But moving back to her still-gutted house has infuriated and depressed her, as she recently indicated with a series of Facebook snaps of an Elf On The Shelf in dire poses in her unfurnished living room.

This wasn't Bippus' first encounter with disaster. More than a decade ago, Bippus lived in Izhevsk, Russia, with the Peace Corps when her apartment building caught fire. She left behind money and passport, but had just enough time to pluck a Russian English dictionary. "Totally impractical," she says.

So when the water invaded her town house last fall, she had given some thought about what to grab. This time she took money, documents and a garbage bag of clothes. She also took a deck of Tarot-style cards, and not because she needed to understand her future. "They're not for fortune telling," Bippus says.

Instead, by randomly choosing one of the cards with their lush, Edwardian images, and phrases such as "rescue" or "unexpected visitors," she can commune with her unconscious self no matter where she is. "It's like doing artwork," Bippus says. "A way to get in touch with my intuition, by meditating on pictures and symbols."

She's still pleased with the choice. "Everything in my house was torn up, everything was chaotic. I needed to do something creative, for my soul," Bippus says.

Mark Austin, a music promoter who manages the much-loved Houston soul band the Suffers, saw similar priorities as he rescued people by van in Harvey's wake. Shortly after the rain stopped, the Fender guitar company quietly asked Austin to distribute 30 new guitars to flooded-out musicians. Ninety percent of the guitarists who fit that description, Austin discovered, had lost everything but their instruments. "Once you find that guitar," Austin said, "you just know it can't be replaced. One guy hid from the water up in his attic. His guitar was the only thing he saved."

Another musician who lost everything else told Austin, "I don't have a really good relationship with my father, but he bought me this guitar. It's the only thing I have that carries a good memory of him."

For people fighting to keep their heads above water long before Harvey struck, though, saving even one sentimental object was a luxury. When the giant NRG Center – home to the Houston Texans – transformed in one day into a shelter for 10,000, it was obvious which flood survivors had no clue where they would go next.

Many who came from poor areas held nothing but blankets and pillows, said Angela Blanchard, president emerita of Houston's Baker Ripley human services agency, and the shelter's organizer. Blanchard's own childhood told her why.

"When you don't have a lot of money, and you go somewhere to visit, you know they're not going to have a couch for you, because someone will already be using it, and they're not going to have a linen closet full of pillows and sheets for you," Blanchard says. "You know you need to bring your own."

Some arrivals at NRG had instinctively prepared for the worst. As each drenched, exhausted guest entered the stadium, polite guards gently labeled and confiscated all weapons. The center's security locked away a couple of dozen guns, some 30 knives – and two rocks.

Other last-minute grabs were fueled by emotional concerns. At 2 a.m. on the night of the storm, after her mother woke her announcing the family of seven needed to flee, 19-year-old Allison Daniel knew what she needed.

Rushing to her closet, she stared for a moment at the water bubbling malevolently through the floorboards. Then she grabbed the soft pajama pants she wears every day after school and some giant fluffy green earrings suitable for a Dr. Seuss heroine. Saving these objects helped to stabilize her after the storm, she believes.

"Oh yes," Daniel says. She has wide, espresso-bean eyes and a childlike jumpiness. "I just wasn't thinking – I brought things that comfort me. My clothes are a really big way I express myself. And my fluffy earrings: They were so fragile. I had to take care of them! These things make my life feel normal."

Clinically speaking, Daniel's split-second choices were quite sound. Even for nonteenagers, what we wear has a measurable effect not merely on our moods, but on our ability to function. In one set of experiments, researchers from Columbia and Rice University asked subjects to slip on crisp white coats. Some were told they were wearing lab coats; others were told they were wearing painters' uniforms.

The subjects who thought they were dressed in doctor garb performed better on attention-related tasks than those who didn't wear the coats. And those who were told the coats were painter's uniforms performed the same with or without the coats on.

But survivors didn't save just their own clothes. Jerriann Nettles, a 43-year-old school teacher, prepared to leave Harvey clutching a Chanel dress that was precious because of the person who could no longer wear it.

Nettles, who had moved to an expansive house outside Houston only the year before, was sure the hurricane would miss her tranquil neighborhood right up until the moment her adult daughter, now in the Coast Guard, called and told her to get out.

Frantically, Nettles and her husband dragged mementos from her daughter's childhood – trophies, tchotchkes, toys – to the second floor. Then, just before plunging into the water to rescue her elderly neighbors, Nettles grabbed her grandmother's Chanel dress. It was silky, covered with deliciously smooth loops of thread. "My grandmother didn't have a lot of money, and she saved to buy this dress from a resale shop," Nettles says. "To this day it still smells like her. She wore Chanel No. 5 perfume. She wore the powder. Anything she had held that combination of her body chemistry and Chanel."

Breathing that scent felt like having her grandmother nearby. "The smell," Nettles says. "It's the last thing on earth you may have on earth from someone's life. If the flood were to take it away..."

Flooded by social media advice about clutter and author Marie Kondo's exhortations to toss those possessions that don't "spark joy," Harvey survivors often apologize when admitting their sorrow. "I know they're only things and it could be so much worse," one man says, standing in the bare kitchen of his small townhouse. Contractors had stripped but not yet replaced the drywall, making it possible to walk straight into his neighbor's dining room. "But they were our things."

That's why, maybe, those items that Houstonians rescued still feel precious: not because of their monetary value, but because they embody the deepest feeling and investment of the individual. It's why we love our kids. It's the reason imperfect shelves built at home give more pleasure than flawless ones from the store, and why we will pay more for a coffee cup if we've cradled it for a little while in our hands.

It definitely explains why Diane Sanchez, bolting from her deluged house, grabbed her hedgehog.

The foul-smelling water sloshed chest-high in the front yard. Helicopters were roaring. Sanchez knew she'd have to leave the fish and the snail behind. But the family loved Auggie, even though one couldn't truly know if he loved them back.

Undeniably cute, with pointy noses and moist button eyes, hedgehogs are largely inscrutable. "They are not cuddly," says Sanchez. "They aren't going to learn their names or snuggle with you." They also dislike other hedgehogs.

What they do offer is the chance to lavish effort upon them. Without constant attention, Auggie would have been downright painful: His unrestrained quills might stab anyone who touched him. To gain a hedgehog's acceptance, its caregivers must carefully hold him in their palms every night (and it has to be night, because they're nocturnal). After several months of this, Auggie gradually began flattening his quills around family members – which is how Sanchez was able to pick him up.

After six months with relatives, the family has just returned to their house. "Figuring out how to put our lives back together is probably the worst thing that's ever happened to me. And I've had cancer twice," Sanchez says. "I feel more out of control now."

But Auggie, impassive as ever, is a sure thing. Her teenage kids adore him, doting on him and taking comfort from the continuity he brings, Sanchez says. Saving their small, prickly pet from the flood might have been her first step toward saving her family, and herself.

This article originally appeared in Gray Matters, Houston Chronicle.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Retail Therapy

Organizations can solve problems by repurposing objects in creative ways.

Based on research by Scott Sonenshein

Organizations Can Solve Problems By Repurposing Objects In Creative Ways

- When workers solve problems by using objects for new purposes, their workplaces can get by with less money spent on infrastructure.

- Encouraging this approach can inspire workers and compensate for a sense of limited resources.

- It's up to managers to nurture this creative mindset.

Academics who study workplace creativity often ponder whether workers are more inspired by limited resources or abundant resources. Rice Business Professor Scott Sonenshein asked another question: How do resources themselves shape an organization’s creativity?

To find out, Sonenshein headed to the mall: specifically, BoutiqueCo*, a retail company that sells clothes, jewelry and accessories at multiple stores. It was an excellent model for studying both big and small business, because it was vaulting from a modest family-run operation to a public chain valued at about $1 billion.

Sonenshein analyzed BoutiqueCo at two distinct moments in its evolution. The first was between 1999 and 2010. For most of that time BoutiqueCo was a family-run business with about 80 stores, although the family did sell a minority stake in the company to a private equity firm in 2008. The second period was between 2010 to the present, after the family relinquished control of the company in 2010 when it sold most of the organization to a private equity firm.

During the family-owned phase, the owners’ lack of retail knowledge, of official managers and of access to capital prompted them to give extra power to their workers, encouraging them to see the store as their own. Peter, one of the owners explained that even if they’d wanted to control the other stores, they couldn’t. “We didn’t have the staff to do it. We didn’t have the resources to do it. We didn’t have the processes to control it,” he said.

This prompted the family to give the store workers far more autonomy than they’d normally have gotten at their level. Employees were free to tinker, try new strategies and solve problems on their own. A culture of creativity flourished — by necessity.

The family’s lack of resources also forced employee self-sufficiency. Left to their own devices, employees improvised new uses for display fixtures, including the merchandise itself. When a sheer cotton dress wasn’t selling, for example, a family member who was also a store manager snipped all the straps, rolled the frocks up neatly and marked them down to market them as beach cover-ups. They flew off the shelves.

Employees took similar liberties with store displays. Lily, an assistant store manager, told Sonenshein workers were allowed to experiment however they wished. “You can move the jewelry tables around, you can dress the mannequins. I mean anyone can do it. It’s the manager, the sales associates,” she said.

The unusual freedom did far more than save money. By allowing workers at the different stores to act independently and creatively, BoutiqueCo’s owners had money and attention to invest in opening more stores.

The investor era ushered in a different mindset. Owners and employees knew more resources were available. Seasoned managers came onto the job. Yet BoutiqueCo stayed creative. How did they do it? By being intentional, Sonenshein discovered.

Despite the wave of new resources, managers purposely withheld fixed objects they thought might dry up employees’ creativity. Unusually for big retail chains, BoutiqueCo never provided a planogram, a data-based management tool mapping out where employees should place items for highest sales. Instead, because of their past success repurposing items and displays, the managers fed the workers’ gift for creative resourcing by offering some guidelines and an array of malleable objects they could use in multiple ways.

Instead of dictating from above, the owners pushed employees to dream up themes or stories for their individual outlets and build displays based on these stories. The employees delivered. In one store, they fashioned a snakey, metallic necklace into an article clothing. Cinching the necklace around a floral dress, workers “topped the ensemble off with a solid cardigan, thin gold chains, and a straw clutch,” a store manager recalled. It became one of the season’s hottest trends.

Corporate managers also gave individual stores autonomy in fixing problems. They let each store have a unique look or personality, banishing the notion that all stores in a chain must be clonishly the same. The result: Employees created stores that catered to the niche markets in their area.

BoutiqueCo’s story shows the power of boldly challenging employee resourcefulness, Sonenshein found. Giving workers a sense of ownership — not just in the businesses’ profit, but in its presentation and even survival — inspired more action from employee and higher sales. Not to mention a better use for that odd-looking necklace.

*Disguised name of company.

Scott Sonenshein is the Henry Gardiner Symonds Professor of Management at the Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To read more, please see: Sonenshein, S. (2014). How Organizations Foster The Creative Use Of Resources. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 814–848.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Diamond In The Rough

Hunting for a deal? Take a look at value stocks, shares that investors think merit higher prices.

Based on research by Yuhang Xing , Huseyin Gulen and Lu Zhang

Mining The Possibilities Of Value Stocks

- Value stocks are company shares that investors think are underpriced. They’ve historically performed better than another popular investment type, known as growth stocks.

- Value stock portfolios respond more to market volatility than do growth portfolios, but they act similarly to growth stocks when markets are calm.

- Because market volatility often occurs during economic downturns, value stocks may be riskier during such periods. On the other hand, value stocks also have more upside potential at these times, because the market rewards risk.

Value stocks are Wall Street’s Two-Buck Chuck. They’re shares that investors think deserve a higher price based on a firm’s sales, profits or other fundamental characteristics.

Growth stocks, on the other hand, seldom show up on the bargain table. Even so, they often lure investors, who bet their prices will rise even more as the companies expand. While both types are popular investments, the less-glamorous value stocks historically get better over time.

The performance gap between the two investment types is called the “value premium.” In a recent study, Rice Business Professor Yuhang Xing joined two other finance scholars, Huseyin Gulen of Purdue University and Lu Zhang of Ohio State University, to review a half-century of data and calculated that the monthly value premium averaged 0.39 percent. They think they know why.

In a multifaceted statistical study, the research team found that value shares are more sensitive to turbulence in the market than are growth stocks.

Every time the stock market looks stormy, value stocks get riskier. But because financial risk also carries the tantalizing whiff of higher returns, value stocks that weather such storms perform quite well. Growth stocks didn’t show the same sensitivity during such markets — and neither type of stock showed such sensitivity when the markets were placid.

To draw their conclusions, the scholars used a statistical method called a Markov process, which views data over time and through varying conditions called states — in this instance, periods of high or low market volatility. The researchers based their model on a study from 2000 that took a similar mathematical approach but asked different questions.

Xing and her colleagues then analyzed the performance of value and growth stock portfolios in each of the 648 months from January 1954 through December 2007. The start time was significant: January 1954 was the effective date of a policy that allowed U.S. Treasury interest rates to rise and fall with the market. The professors used the Treasury rates starting that month as a thermometer for measuring market volatility.

They found a correlation between high market volatility and recession and between low market volatility and economic expansion. The link wasn’t perfect, but occurred often enough for Xing’s team to conclude that economic slumps affect value stocks more than growth stocks.

The researchers also used one-month Treasury bill rates as one of several benchmarks for assessing how growth and value stocks performed. These rates are a favorite of financial professionals who are calculating returns on risk-free investments, because the U.S. government backs the nation’s debt. (Treasury bills are loans to the government for a year or less.) Investors can lend with the confidence that Uncle Sam will pay them back with interest — though not much interest, because of Treasury bills’ low risk. T-bills currently pay around 1 percent annually, according to treasurydirect.gov, the official website for purchasing Treasury securities.

Logic dictates that stocks are riskier than Treasury securities, because share prices wax and wane with firm performance, the market and the economy. So why do value portfolios outperform portfolios with growth stocks?

The answer: Value companies often are established players in mature industries. Many distribute some of their profit to investors through quarterly dividends. They’re a bit like a bargain wine from the grocery store — adequate, if unglamorous.

Growth companies, meanwhile, typically invest most of their income in expansion and product development rather than paying out dividends. They often offer breakthrough technical devices or innovative services.

Earlier research suggests that because value companies typically are better established than growth firms, they are less nimble in responding to worsening economic conditions. The value of their financial and physical assets, which accountants call book value, stays about the same. But their market value — the sum price of all a firm’s outstanding shares — falls because of their potential for sluggish response to hard times.

At that point, like a not-so-fancy bottle of wine, value stocks live up to their name. Labels aside, investors think they’re worth more than they cost.

Yuhang Xing is an associate professor of finance at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Gulen, H., Xing, Y., & Zhang, L. (2011). Value versus growth: Time-varying expected stock returns. Financial Management, 40(2), 381-407.

Never Miss A Story

You may also like

Keep Exploring

Big Picture

Dashboards alone do not provide value; it's up to marketers to distill insights.

By Vikas Mittal

Dashboards Alone Do Not Provide Value; It's Up To Marketers To Distill Insights

Companies rely on dashboards to improve customer value—about 40% of the large U.S.-U.K. companies report efforts to build and use a dashboard. In some ways, dashboards are an evolution from the earlier practices of using control charts, scorecards, tracking studies and metrics-based snapshots. Fueled by advances in data analytics and visualization, marketing dashboards are becoming integral components of a company’s decision support system.

There are advantages to using a dashboard:

- A dashboard visually displays a consistent set of metrics that can be monitored at a given point in time (cross-sectional) and over time (longitudinal).

- This enables management to communicate trends in inputs, processes and outcomes with key stakeholders.

- A dashboard may also be used for planning purposes; key metrics that are part of the dashboard can represent goals to be achieved.

- Management can develop plans around measurable goals and further use a dashboard to monitor progress.

Don’t let dashboards make decisions tactical and reactive.

Many marketing dashboards capture an increasingly smaller slice of time, space and experience. Annual tracking of customer satisfaction became quarterly, then weekly and has become daily, even hourly, in some firms.

This all sounds great. Presumably, armed with more information, more data, more visibility into the customer experience, marketers can make better decisions, become more strategic and provide a competitive edge. The risk is that managers who are using detailed and elaborate dashboards may make suboptimal decisions due to information overload.

More importantly, the smaller slices of information that populate dashboards can make them more susceptible to outliers. Compared to yearly data, daily data—within a single retail outlet, based on a few customers—can be quite volatile. One or two customers—ecstatic or irate—can spike the daily average for an outlet. Focusing on these spikes can make managers reactive.

To avoid the “more is better” trap, step back and carefully delineate the role a dashboard should play in marketing decisions. A useful dashboard can help set goals, monitor performance, provide implementation metrics and help to provide strategic insights. How often do you need it and at what level? Answer these questions before you decide on the frequency and granularity of data used in your dashboard.

Don’t let dashboards mask strategic trends.

Dashboards that focus only on cross-sectional information can mislead. The cross-sectional information in a dial should be supplemented with long-term longitudinal trends to provide a strategic overview. Good dashboards should also display longitudinal trends relative to a control group (industry average, select competitors and aspirational firms outside your industry). From 2010 to 2013, the administration at a business school in Texas continuously showed a dashboard with increasing average salary of its MBA students as a KPI. Without a control group, no definitive conclusions could be drawn. Was the increase higher or lower than the increase experienced by other MBA programs in Texas? Was it higher or lower than the salary growth in the Texas region?

Don’t let dashboards focus on analytics at the expense of insights.

Due to their emphasis on quantifiable information, dashboards can push users to focus on analytics—trend lines, bar graphs, pie charts and dials. Is a metric increasing or decreasing, and by how much? How did an opinion or an attitude change since the last period? What percent of people engaged in a specific behavior? How does one subgroup compare to another on key survey items?

Answers to these questions may seem important but are not necessarily insightful. At worst, a focus on answering these types of questions can be utterly misleading. Recall the “dashboard mentality” exhibited by many in the media during the 2016 presidential election. Focused on analyzing the results of day-to-day polls, many in the media failed to gain insights. Every little change in day-to-day polls was overanalyzed. The media gurus became analysts—focused on analyzing one variable at a time: What percentage will vote for the Republican or Democrat candidate? Which issue is more important to which subgroup? Wading deep into analytics, they were unable to provide insights.

What is an insight, and from where does it originate? A practical way to answer this question is to distinguish between the what, why and how of a phenomenon. The “what” pertains to analytics, while the “why” and “how” provide insight.

What is the state of affairs? This can be answered using univariate data analysis—analyzing one variable at a time and comparing it among different subgroups: What percent of people say something? What is the level of agreement, satisfaction or intent based on some survey or behavioral metric? Dashboards adeptly answer “what” questions by displaying dials, trend lines, bar charts and pie charts.

Why is the state of affairs occurring? Why are the people saying something? Why is the level of agreement, satisfaction or intent relatively low or high? To answer these questions, you have to conduct qualitative research—in-depth interviews and prolonged observations—with your customers, coupled with multivariate analysis to understand how multiple variables are related to one another. In most cases, it is a combination of multivariate analysis and in-depth qualitative research that provides the insight—answering the “why” behind the “what.”

How can the state of affairs be influenced? A clear understanding of the “why” helps influence key processes that change future outcomes. A focus on how—by design—is forward-looking and requires an attention to detail to understand the drivers of the desired outcome and an understanding of the process. Companies that can supplement their dashboard with a process to answer the “how” create an enduring and unique capability. Doing this requires employee engagement through discussion forums.

Don’t let dashboards become an end, make them a means to facilitate discussion.

Dashboards, in a rudimentary form, were introduced in the early 1950s by W. Edwards Deming, Joseph M. Juran, and Walter A. Shewhart within the context of total quality management (TQM). TQM used complex statistical tools and experimental methods to generate data that were summarized and visually presented to front-line employees in the form of quality control charts.

The genius of the TQM approach was not in visual analytics. It centered on using visual analytics to generate insights. TQM did that by embedding the analytics in discussion forums such as quality circles. After presenting the dashboard analytics, discussion forums encouraged employees at all levels to elaborate upon the information. The insights generated helped address decision making, enhance manufacturing processes, frame the goal-setting process and develop incentives.

Frequently, it was not the metrics, but the discussions facilitated by the metrics, that led to quality improvement suggestions by employees. Dashboard analytics are important, but insights based on a discussion of the analytics are paramount.

Dashboards replete with numbers will not provide insights. To gain insights, embed the dashboard metrics within forums that facilitate discussions, generate ideas and motivate employees to more systematically use the “what” to move into the realm of “why,” and “how.” Do this at all levels frequently, and consider involving a core group of other stakeholders—customers, suppliers and investors—to broaden the pool of insights.

An exclusive reliance on marketing dashboards can be counterproductive for strategic thinking and decision making. To get the most out of your dashboard, use them as facilitators of discussions that yield insights. Keeping the dashboard simple, graphical and forward-looking will help the discussion. Provide a decision support system that can bridge the journey from analytics (what) to insights (why, how). Only by making your dashboard a vital part of a broader decision support system can you extract the most value from it.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Management in Marketing at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice Univeristy.

This article first appeared American Marketing Association's as The Downside Of Marketing Dashboards.

Never Miss A Story