Under Pressure

What happens when coercive leaders feel cornered?

By Thomas Kolditz, founding Director of the Ann and John Doerr Institute for New Leaders.

What Happens When Coercive Leaders Feel Cornered?

This op-ed origianlly appeared on The Hill.

To leadership experts, Donald Trump has never been a particularly interesting exemplar. He mostly manages with coercive power — fear — and such a leadership style is all too common in formally appointed business leaders.

In addition to being common, the outcomes are predictable. Early research in leadership, by classic researchers John French and Bertram Raven in the 1950s, predicts that fear-based leadership leads to high levels of outward compliance but low levels of follower loyalty.

In other words, people who work for a leader like President Trump will do what he wants if they are vulnerable to him, but tend to be disloyal when not under his direct influence. This is why formerly loyal associates like Michael Cohen are willing to flip when confronted with something worse than the president’s wrath — namely jail time.

We can expect much more of that behavior as others leave the White House, particularly if they are indicted. It’s predictable and common, and uninteresting from a leadership perspective.

The recent anonymous op-ed in the New York Times, indicating significant disloyalty and undercutting of the president by his senior staff is interesting, even if it is also somewhat predictable.

The majority of the American people, that majority that did not support President Trump, are experiencing considerable angst over perceptions of disarray in the West Wing.

The anonymous op-ed writer clearly intended to put some of us at ease by revealing hard work (if surreptitious work) by the president’s staff to avert major disasters.

Given the president’s coercive style and his lack of familiarity with the workings of the government, it is not surprising that senior staff members are focused more on their constitutional obligations than on blind obedience to the president. That one of them anonymously reported this to the people of the United States seems almost expected.

What becomes much more interesting to leadership experts, however, and should be of interest to every American, is what happens now? What is the probable effect of having a group of dissenters in the White House staff?

Earlier research published in the Academy of Management Journal in 2012 and 2014 by Burris & Associates forewarns a pessimistic and dangerous reaction by a leader in President Trump’s circumstances. The work centers on leaders who are ego-defensive and challenged by subordinates.

The research suggests three distinct reactions by President Trump, all of which are disastrous for his ability to lead. First, he is likely to identify his staff as less competent and to listen to them less than before being challenged by the op-ed.

The opposite would be true for those he knows for sure are loyal — but exactly who might those people be? Thus, for those who are worried that President Trump tends not to listen to staff, hold onto your hats, it is likely to get much worse.

Second, the research would predict that the op-ed would trigger ego defensiveness because the letter is an unquestionable threat to the president’s self-image. This defensive stance will cause an increase in the president’s tendency to denigrate people, especially people with suggestions counter to his.

Such ego protective behavior will manifest in a near paranoid suspicion of other around him — something already apparent in his personality.

Lastly, the research strongly suggests that staff who are subjected to such treatment will partially (or perhaps entirely) shut down.

Almost certainly there will be a marked decrease in constructive dialogue around the president, and there is likely to be a decrease in the constructive dialogue among the White House staff themselves, given the risk of an unwanted idea being proffered to the president.

President Trump has now become an interesting leadership exemplar. The existing leadership literature clearly predicts a rapid, dramatic increase in many of the negative presidential leadership qualities and outcomes highlighted recently in books by Bob Woodward and Omarosa Manigault Newman.

Time will tell, but the unfolding of the story should now have the attention of everyone who believes that leadership based on character rather than coercion is an essential quality in the leader of the free world.

Tom Kolditz is the founding director of the Ann and John Doerr Institute for New Leaders at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Act II

Raising the curtain when your artistic vision has been swept away.

By Tarra Gaines

Raising The Red Curtain When Your Artistic Vision Has Been Swept Away

Like many Houston arts organizations after Hurricane Harvey, Mildred’s Umbrella, a women-centered theater company, struggled through months of fund-raising and rent-induced financial stress. For Jennifer Decker, Mildred’s founder and artistic director, producing shows had become less like art and more like toiling on an assembly line as they raced to keep ahead of bills. Finally, Decker had to face the question: Should she try to keep up with the frantic pace of a traditional theater company – or step away from the conveyor belt and remake Mildred into something smaller, nimbler – different?

Most of us, including artists, prefer our drama onstage rather than in real life. But disasters such as flood, fire and personal adversity are inevitable, forcing artists and arts groups to perform without a guiding script or score. And an unscripted future can sometimes lead to occasional, magnificent, second acts.

Rice Business professor Otilia Obodaru is an expert on liminal experiences at work: those uncertain periods of transition between careers and roles. While these times naturally fuel anxiety, she said, they may lead to greater identity growth and self-discovery. For artists, especially, this can be a breakthrough.

“The key advice about how to use liminality,” Obodaru said, “is to deliberately engage in identity play, to see the liminal period as a time to experiment with possibilities and to do exactly that — try on a variety of what my research co-author Herminia Ibarra calls ‘provisional selves.’ You see how you feel when you are trying to be that kind of person.”

This process helped transform one of Texas’ most innovative theater companies, the Rude Mechs. For almost two decades, the group created and performed new works while participating in community outreach from their East Austin performance warehouse, the Off Center. Then their landlords, the University of Texas, raised the rent 300 percent and the Mechs had no option but to leave. They were faced with the choice of giving up or experimenting with a different identity.

They chose the latter. Settling temporarily in the old Austin American-Statesman warehouse, they had to come to terms with semi-homelessness. Then they went further and embraced uncertainty, announcing crushAustin, an experimental period of new work and initiatives in alternative venues across the city.

“The work is lean. A lot of it fits in a suitcase or an app,” co-artistic director Kirk Lynn said. “The primary tools are minds and bodies and dreams and early mornings and bad attitudes and a lot of love.”

In Houston, theater director Decker made a similar external change. She ended the long-term lease of Mildred’s home near the Houston Heights and moved it to short-term rented theater space. Then, to salvage the group’s creative integrity, she quit the assembly-line approach and shifted from four full productions to two.

“It will be tremendously productive creatively, because we’ll have time between the productions to really dig into the art,” Decker said. “It will allow me to participate more often myself as an artist, the reason I was drawn to theater in the first place, and it will give us more time to plan and collaborate as a group.”

Dallas dance company Bruce Wood Theater had to find its way through a different sort of liminal fog. In 2014, just three weeks before the world premiere of its new work Touch, founding choreographer Bruce Wood died. Without their visionary leader, the dance company had to choose whether to die as an organization — or be reborn.

“We went forward ‘Bruce-style,’ as we called it,” executive director Gayle Halperin said. In his last years, Wood carefully mentored protégés and emerging choreographers. Since his death, the group has focused on furthering that mission, commissioning new works and cultivating choreographers from within.

According to Obodaru, this reinvention process is akin to the strange, sometimes awkward experience of trying on piles of unfamiliar clothes. “See how they look on you, whether they fit, and how other people react when seeing you in these new clothes,” she said. “Allow yourself to try on things you would have never considered before, precisely because the point is to experiment.”

Rebecca French, founder of FrenetiCore multimedia dance theater and the Houston Fringe Festival, is another artist who faced disruption, in this case from within her nonprofit. Her decision: moving on.

As the founder, she was told in 2016 that she had the option of dismissing the entire board and staff and keeping the nonprofit. But because she wanted to see the Fringe Festival continue, she chose to walk away.

Two years later, French has found the she is creating as many new projects and championing as many artists as she always did, but now sees a once-frightening future as filled with possibility.

“There were certain risks that I didn't feel comfortable taking as the head of my former nonprofit because certain stakeholders might not approve,” she said. “Stepping away has allowed me to have complete control over each project that I choose to create.”

Tarra Gaines is a Rice Business Wisdom guest contributor.

A version of this article first appeared in Arts And Culture Texas as "Second Chapters: Texas Artist Navigates Change."

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Hand In Glove

What values should businesses observe besides profits?

Based on research by Duane Windsor

What Values Should Businesses Observe Besides Profits?

Never miss a story! Join our free monthly newsletter.

- Virtuous behavior doesn’t necessarily conflict with rational self-interest and stakeholder wellbeing, Windsor finds.

- A near-universal principle of ethics is to do no harm without an acceptable moral justification, which could be a basic premise for businesses.

- Businesses should only be willing to cause harm if it can be justified in narrow circumstances, such as in legitimate competition that might harm a rival firm.

Flames filled the air and the saltwater licked fire as thick, hot oil spread through the Gulf of Mexico. The Deepwater Horizon explosion killed 11 people and resulted in incalculable environmental damage. In the aftermath, government agencies found British Petroleum responsible for one of the worst offshore disasters in history, arguably the result of corporate cost-cutting and inadequate safety precautions.

How do tragedies like Deepwater Horizon fit with the popular idea that firms are the best police for their own industries? Is there even such a thing as a foundation for business ethics – one on which most people would agree?

Rice Business professor Duane Windsor set out to define such a foundation, arguing that virtuous behavior in the business world does not necessarily conflict with rational self-interest and stakeholder wellbeing. Such an ethical foundation could even function in fields where scarcity often predominates and players must fight for advantage, Windsor argues.

Sound business ethics can be based in a variety of philosophical and spiritual systems, according to Windsor. Many religions, including Islam and Judaism, explicitly promote business ethics. Philosopher Immanuel Kant argued that an act is not right or wrong because of its consequences, but based on whether it fulfills the supreme moral duty he labeled the Categorical Imperative.

Virtue theory takes a different approach, arguing that character, rather than duty, should underpin human actions. And utilitarianism maintains that actions are right if they lend themselves to the greater good of the majority.

What about in the workplace, though? Can a moral science for business really spring from a universal foundation? And can such a foundation be non-controversial and coexist with the assumption that managers act rationally for self-interest?

In each of the theories mentioned above, a fundamental ethical principle is to do no harm without an acceptable moral justification. A moral science of business ethics should proceed from this simple premise, which is nearly universally agreed upon, Windsor argues.

At the same time, many business decisions obviously cause harm to someone: competitors, dismissed employees, or out-negotiated suppliers. These decisions are not necessarily morally wrong, though, if they can be justified and if they are accepted or regulated by the political community. Even so, the question remains: Is economic rationality compatible, or by nature antithetical, to business ethics?

Adam Smith advocated for separating business from morality, praising self-interest and scoffing at those who affected to act in the public interest. In Smith’s view, competition would regulate self-interest, courtesy of the market’s famous invisible hand. Modern businesspeople who oppose ethically-based business education still agree, arguing that markets are self-correcting and that voluntary self-regulation is sufficient.

The AACSB, the main accrediting group for American business schools, takes a different position, maintaining that ethics, social responsibility and sustainability should play a pivotal role in business school curricula. Nevertheless, the AACSB does not promote discussion of how uniformly to implement these standards. Instead, a technical or scientific approach – one that emphasizes economics and psychology – has shaped business school ethics in the United States.

And some in the business world actually object to the teaching of business ethics, calling the endeavor quixotic. Moral values, they argue, are subjective, and conventional business ethics tends to simply fuel self-serving rationalization. Some in this school of thought argue that the sole purpose of business is to maximize wealth for owners.

Cultural relativism also stymies ethics education for students of international business, since what’s ethical in one country may be downright criminal in another.

Windsor takes a very different view. American firms should adopt a principled basis of operation, he argues, and refuse to cause unjustified harm. Although arguments can be made about what constitutes harm and whether some forms of harm are acceptable, some types of harm should not be acceptable in any industry.

All firms, Windsor argues, should avoid practices that lead to direct harm. But harm may not always be as direct as an oil spill. The so-called Vitamin Cartels that wreaked havoc on pricing during the 1990s show how monopolization can harm consumers, while AT&T has been fined for deception and fraud in communications transmission.

None of these acts of harm, Windsor says, can be justified. Instead, he writes, American business leaders need to concern themselves with moral leadership and social responsibility. In his view, the primary job of business is to create social good. That principle means protecting the wellbeing of the organization, its employees, its customers – and the world around them.

Duane Windsor is the Lynette S. Autrey Professor of Management and Strategic Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Windsor, D. (2016). “Economic Rationality and a Moral Science of Business Ethics.” Philosophy of Management, 15, 135-149.

This paper, presented at the 2015 Philosophy of Management Conference at St. Anne’s College, University of Oxford, was recognized as the best paper of the conference.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

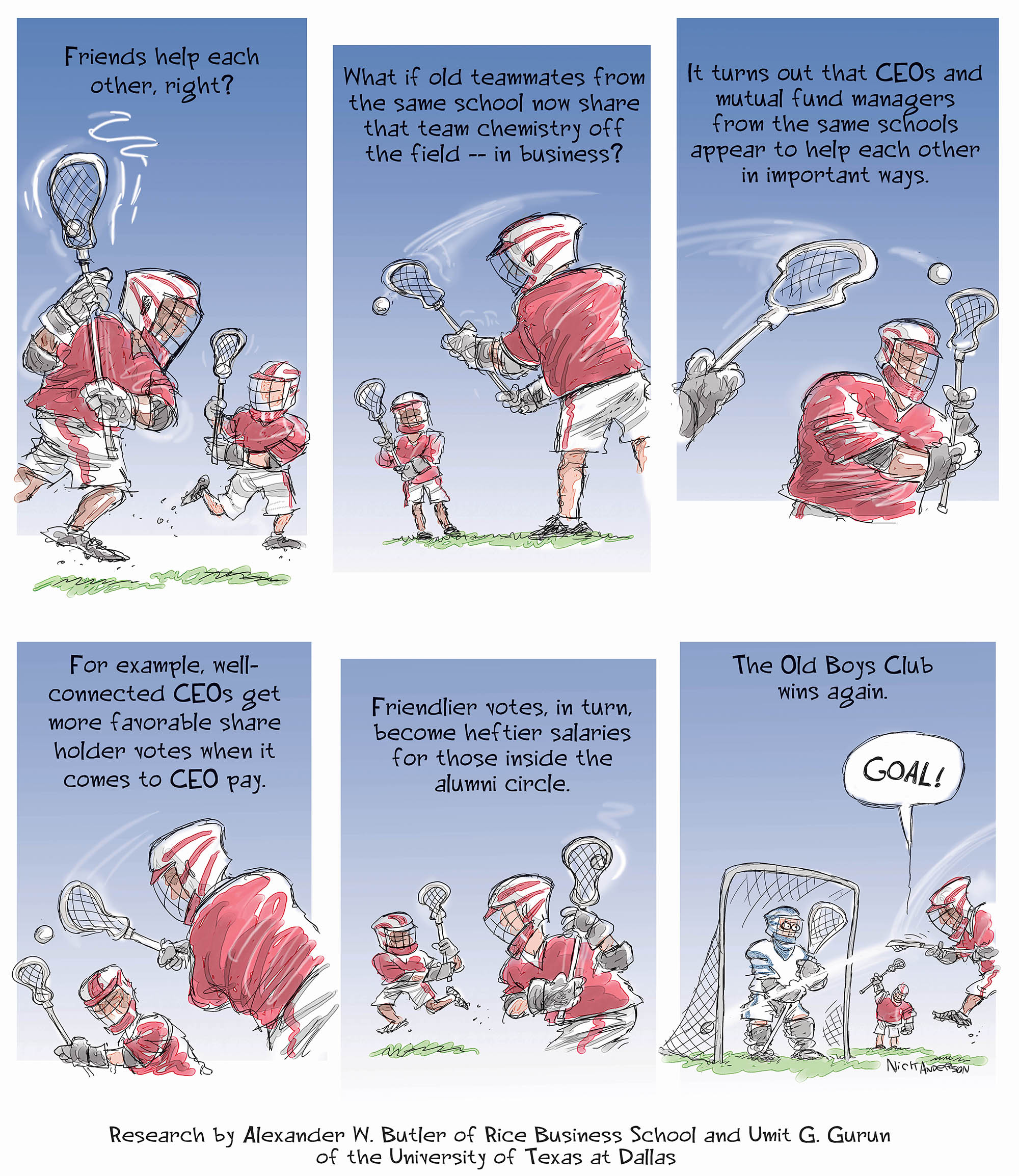

Old Boys Club

That glow from old school memories shines on...in CEO pay.

Illustrated by Nick Anderson. Based on research by Alexander W. Butler.

That Glow From Old School Memories Shines On ... In CEO Pay.

Sports, parties, friendship — there's so much to savor about college memories. For CEOs who graduated from the same schools as board members, there's even more to savor: better chance of a pay raise. The nostalgia is not quite so fun for leaders who don't share those school ties. Rice Business professor Alexander W. Butler explains the business perks of belonging to the alumni club. Cartoonist Nick Anderson shows a glimpse of the playing field.

Alexander W. Butler is a professor of finance at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Nick Anderson is a Pultizer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Crosscurrent

How speedy loan-loss recognition can save banks billions.

Based on research by Brian Akins, Yiwei Dou and Jeffery Ng

How Speedy Loan-Loss Recognition Can Save Banks Billions

- Timely loan-loss recognition can work as a powerful tool in fighting corruption in the banking sector.

- The faster a bank recognizes a problem, the easier it is to address the issue.

- Recognizing losses quickly, however, only really matters in places without government ownership of banks.

The loans should have been sure things. Two high-profile lenders — Russia’s VTB Bank and Credit Suisse — provided $2 billion to two government-backed companies in Mozambique. What happened next was a corruption case of epic proportions.

The funding, approved five years ago, was meant to support a tuna fishing fleet and naval protection for vessels operating out of the southern African nation’s territorial waters. Credit Suisse and VTB pocketed $200 million in loan fees.

The only problem: The two companies were woefully mismanaged and never generated any meaningful revenue. And to this day, at least a quarter of the money remains unaccounted for. It’s not even clear that it ever arrived in Mozambique: The banks sent the funds to offshore companies in Abu Dhabi. Meanwhile, Mozambique’s parliament was never informed of these government-backed loan applications — nor was the public.

How can banking institutions avoid entering into corrupt deals like this? And how does corruption on this scale happen in the first place? Rice Business professor Brian Akins, along with Yiwei Dou of New York University’s Stern School of Business and Jeffrey Ng of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s School of Accounting and Finance, delved into these questions in a recent study.

What they found is that banks can better address corruption if they quickly recognize when they’ve made bad loans. It’s an important finding because loan-loss recognition is a relatively simple way to stem corruption, and little research has been done on the effects of quickly spotting bad deals.

The researchers examined the records of 3,600 firms across 44 countries and found that timely loan-loss recognition decreased the likelihood of corrupt lending practices. The quicker banks recognize a problem, the easier it is to address the issue quickly.

Loan-loss recognition matters because it provides investors and depositors information they can act on, according to Akins and his colleagues. Investors who see that banks are making corrupt loans are likely to correct the issue quickly. Depositors won’t stay with a bank very long if they know it is wasting the money in their accounts on bad loans.

But the study notes that in countries where banks were largely owned by the government, there was a greater chance that the lending institution would be bailed out in the event of loan failure. That is to say, there was less in the way of incentives for speedy loan-loss recognition.

The greater the government involvement in a banking institution, the less likely it was that outside stakeholders would monitor the banks very closely, the study shows. “Government ownership of banks leads everyone else who is supposed to be monitoring the bank to just let it go because they expect the government to back their claims on the bank if it fails,” Akins explains.

Deposit insurance, too, works as a disincentive for outside stakeholders to monitor banks closely. Loan-loss recognition doesn’t work as a disciplining mechanism in this case because depositors have the security of knowing that their claims are backed by insurance. And banks have a greater incentive to take risks. After all, if the loans fail, the burden will fall to taxpayers.

The Mozambique case was hardly unique. In 2014, the Indian government fired the chairman of the state-run Syndicate Bank for taking bribes in exchange for loans, while in 2012, the head of one of China’s largest banks, The Postal Savings Bank of China, was arrested on charges of bribery and illegal lending.

In developing countries especially, corruption plays a big part in the way wealth is distributed. A $2 billion dollar loan anywhere is a large sum, but in a country like Mozambique, it amounts to a sizable portion of the nation’s wealth. That is to say, protecting against corrupt lending practices through timely loan-loss recognition amounts to yet another tool to ensure that economic resources are more likely to go to those who need them instead of a corrupt few.

Brian Akins is an assistant professor of accounting at the Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Akins, B., Dou, Y., & Ng, J. (2017). Corruption in Bank Lending: The Role of Timely Loan Loss Recognition. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 63, 454–478.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Watershed Moment

Harvey washed away homes, jobs and memories; it also brightened a few reputations.

By Clifford Pugh. Photo credit to James Zhao '15

Harvey Washed Away Homes, Jobs And Memories; It Also Brightened Some Reputations.

Moments of crisis bring out our best and our worst. Some people emerge from catastrophe bathed in praise for their heroism; others are drenched in public disdain for their actions in the same moments.

That’s what happened with Hurricane Harvey.

Whether they were big corporations, small businesses or struggling nonprofits, the storm gave an array of Houstonians the opportunity to shine – even if they didn’t think of that during the downpour.

In times of calamity, most people aren’t thinking about their personal brand, says Utpal Dholakia, a marketing professor at Rice Business. “How they behave in normal times is how they are going to behave in an emergency or a disaster,” he says. Nevertheless, Dholakia adds, personal and institutional brands often are profoundly affected by how people act at those times. “Every action that they perform in good and bad times is going to have an effect on their reputation.”

A year after the worst natural disaster in Houston’s history, here’s a look at some of the people and organizations whose credentials were enhanced by their instincts – and some whose names were tarnished by what they did when the chips were down.

Halo Enhancers

In the decades before Harvey, Jim “Mattress Mack” McIngvale was best known as the loudmouth owner of Gallery Furniture who promised to “Save You Money!” in incessant TV commercials. But when Harvey pummeled his community, another side of McIngvale emerged. He transformed his stores into temporary shelters and told evacuees to “come on over” in a Facebook video. He gave out his personal cell phone number. And for those who couldn’t make it to a store on their own, he dispatched delivery trucks and drivers to haul them to safety.

Since then, McIngvale has given hundreds of thousands of dollars to help those hammered by Harvey, and he and his wife, Linda, have launched an ambitious program to offer job training and other community services at their stores.

“We believe in unity and community,” McIngvale told Furniture Today. “Our thoughts have always been, ‘If we went out of business, would the customer miss us?’ This is another way to become part of the community.”

Houston Texans superstar J.J. Watt had less of a transformation to make. Just when it seemed he couldn’t be more beloved, Watts burnished his halo with a Harvey relief fund that brought in a whopping $41.6 million from 200,000 donors. In a recent Twitter post, Watt’s foundation called it “the largest crowdsourced fundraiser in world history.”

Watt’s efforts have enabled repairs to more than 600 homes and 420 child-care centers and after-school programs. They’ve allowed distribution of more than 26 million meals, offered mental health services for more than 6,500 individuals and bought medicine for more than 10,000 patients.

Watt, who has received a host of awards for his Harvey fundraising, including the NFL Walter Payton Man of the Year Award, has laid out a plan for the coming year as well: Funds will go toward continued home restoration, physical and mental health services, rebuilding damaged Boys & Girls Clubs and support for food distribution with Feeding America.

In Purgatory

Lakewood Church, by contrast, is still overcoming its Harvey moment. After its perceived sluggishness in opening its doors to those seeking help, the church led by Pastor Joel Osteen has been working to rehabilitate its reputation. Osteen got a recent boost from megaproducer Tyler Perry, who took to the pulpit to praise Osteen’s response to the storm during a nationally televised Lakewood service.

Lakewood also gleaned a city proclamation for its contributions after the floodwaters receded, such as providing $5 million in financial assistance and supporting 9,300 volunteers who aided more than 1,100 Houston-area families.

However, the proclamation prompted a storm of criticism on social media. In its wake, a city official revealed that Houston made 3,600 such proclamations in 2017, and that anyone could apply for one online or by mail.

Pitching In

The Islamic Society of Greater Houston weathered the storm differently. Before Harvey hit, the organization had already prepped several of its mosques to offer temporary refuge for storm evacuees.

Members who lived near the mosques brought in clean sheets, towels, diapers and food, while hundreds of volunteers worked around the clock to run the shelters and distribute supplies. Dozens of Muslim doctors also volunteered at the citywide shelters in the George R. Brown Convention Center and NRG Center.

The society raised $275,000 to help members of the Muslim community, plus another $300,000 for the community at large.

M.J. Khan, the organization’s president, estimates that around 40 percent of the Houstonians who took refuge in the mosque shelters were non-Muslims. Religious affiliation didn’t matter. “The first thing on the minds of people in the community was, ‘What can we do?’” Khan says. “We knew in a time like this we had to step up and help out. We take it as our responsibility to help our fellow human beings.”

Strange Bedfellows

And then there were the odd couples. These days few Republicans and Democrats play well together, but Harris County Judge Ed Emmett (Republican) and Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner (Democrat) were universally praised for the way they stood shoulder to shoulder as leaders in the crisis.

They appeared on TV together so often during Harvey that it became a crowd-pleasing bromance – one that continued as they both urged voters to approve a $2.5 billion bond issue to more than quadruple annual funding for flood control in Harris County. The bond issue passed overwhelmingly.

Weather Watchers

Houston-based meteorologist Eric Berger gained countless new fans during the storm with his reports on Space City Weather, a website he founded to “cover Houston weather news and forecasting with accuracy and without hype.” Soft-spoken and camera-shy in daily life, the former Houston Chronicle reporter was the subject of a gushing profile in Wired magazine, titled “Meet the Unlikely Hero Who Predicted Hurricane Harvey’s Floods.” Berger has since become a hotly pursued public speaker.

Harris County Flood Control District meteorologist Jeff Lindner also drew a large following with his frank and concise live updates on Harvey’s water levels. Lindner now has 21,000 Twitter followers.

Small Business Winners

Overall, it was figures such as Berger, people not normally in the spotlight, who were most likely to transform their public profile during Harvey, Dholakia says. That also applies to the small businesses and local mom-and-pop restaurants that stepped up to help their neighbors during the storm.

Dholakia cites Proud Pie, a coffee shop and artisan bakery in Katy, where owner Scott Chapman was active on social media during Harvey and offered free meals to first responders and the Cajun Navy. Chapman also opened his food truck in the parking lot of Grace Methodist Church and served 200 free meals a night for four nights to displaced families.

“One year after Harvey, they are one of the most popular restaurant/food shops in Katy,” says Dholakia. “People remember that there was a store owner who helped and was very proactive during the crisis.”

On the other side of town, at El Bolillo Bakery, seven employees rode out the storm by baking the store’s signature Mexican rolls for two straight days. Trapped in the store by high waters, the staff turned 4,000 pounds of flour into nearly 5,000 pieces of bread.

Owner Kirk Michaelis eventually rescued the bakers and took them to his home. “The next morning, they said they were ready to get back to work,” he said. “By 1 o’clock the next day, the stores were open and there was a line of people down the street. It was tough because a lot of my employees lost everything. And they still showed up to work.”

Employees took the excess bread to citywide shelters first, and then to smaller churches and shelters that hadn’t received the attention the larger ones had.

Since then, Michaelis says, “our business has increased, because people read about it and responded, although we didn’t do it for that reason. It’s like paying it forward; people started coming back.”

The city of Houston has proclaimed September 27 El Bolillo Bakery Day. To celebrate, Michaelis is planning a “share day” at the store’s three locations, offering five free bolillos or pastries for every five purchased.

“Hopefully you will share them with someone that helped you during Harvey,” he says. “We want to keep it going.”

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

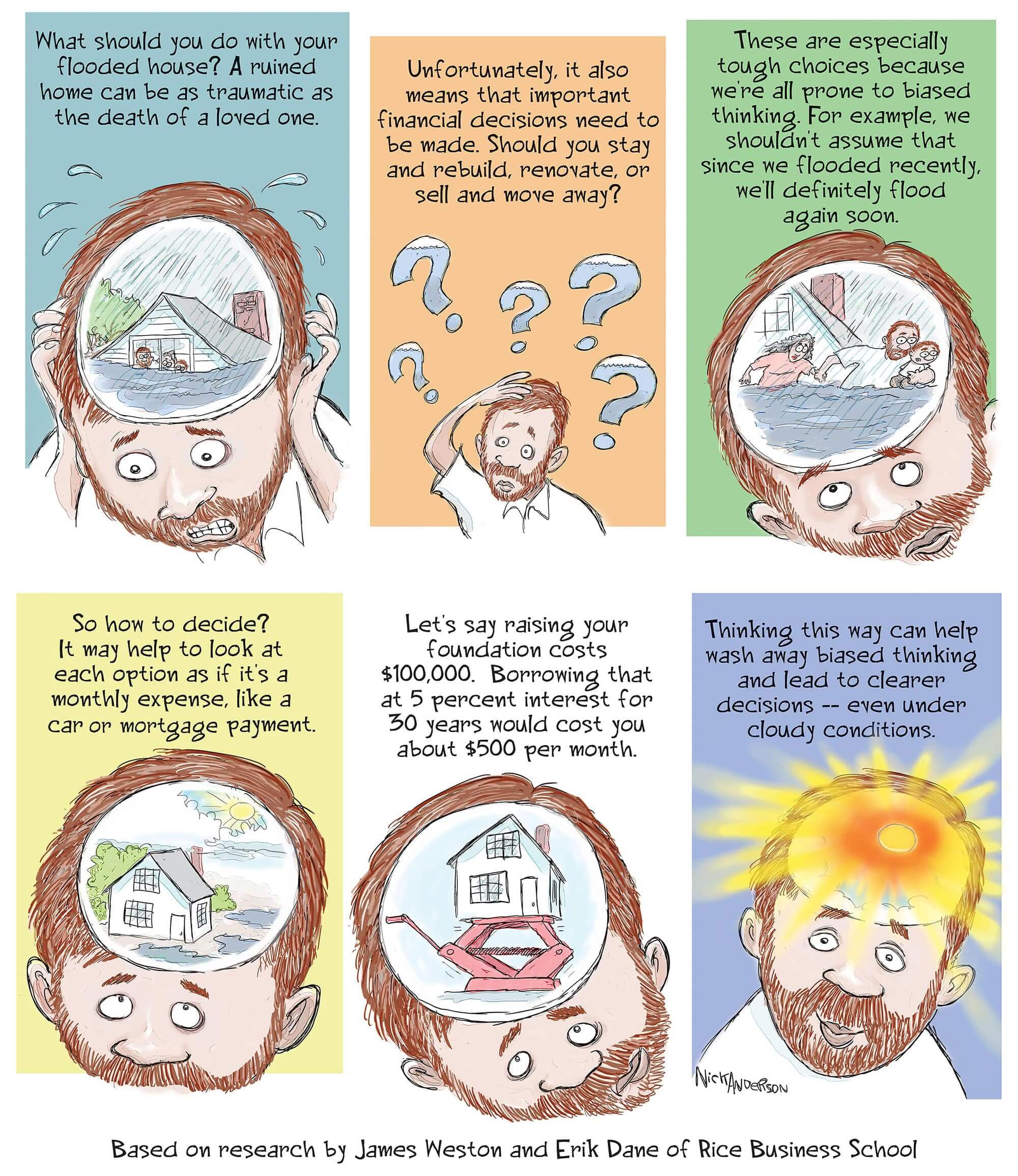

Up In the Air

How do you decide whether to sell your Harvey-drenched home?

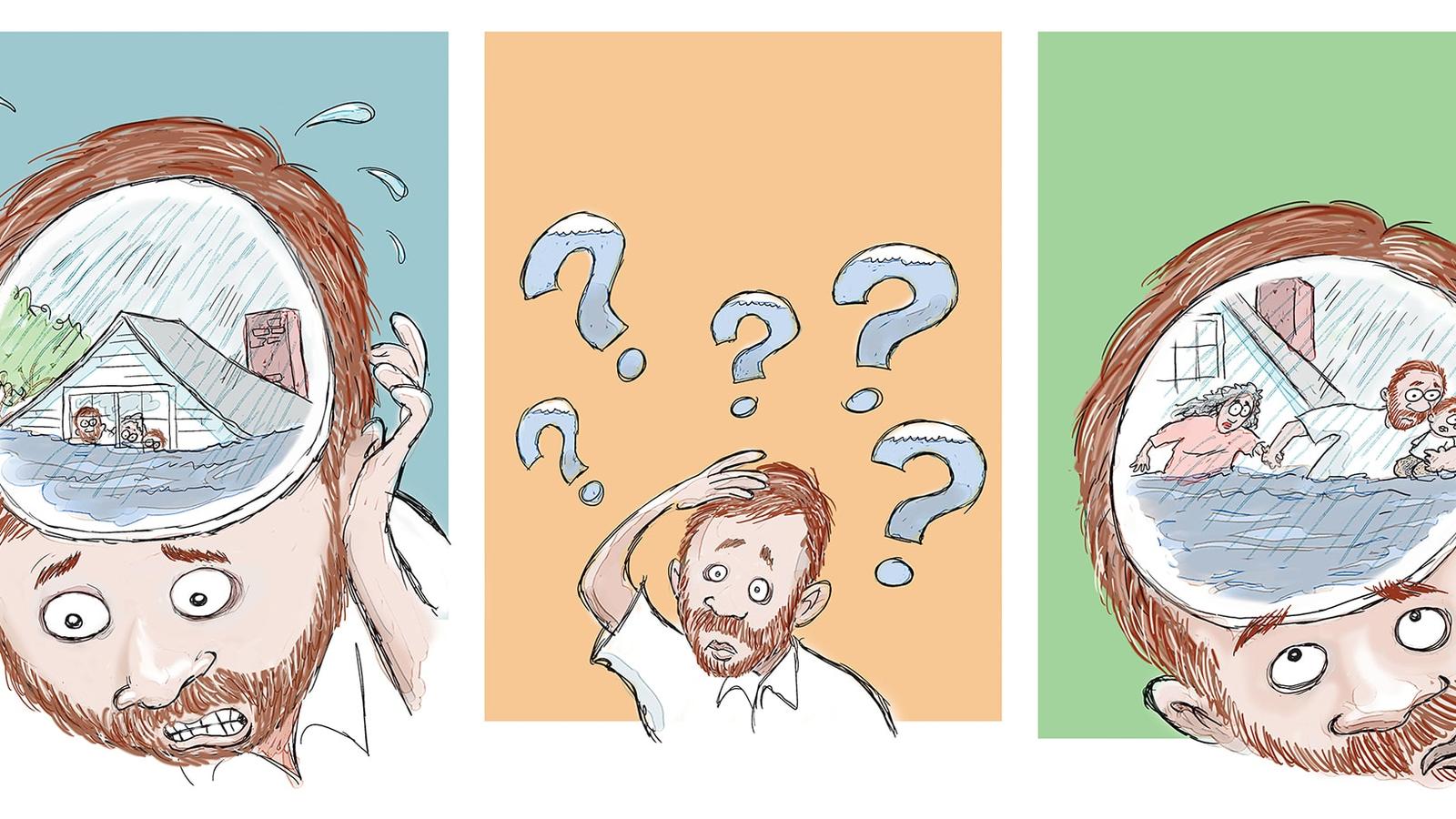

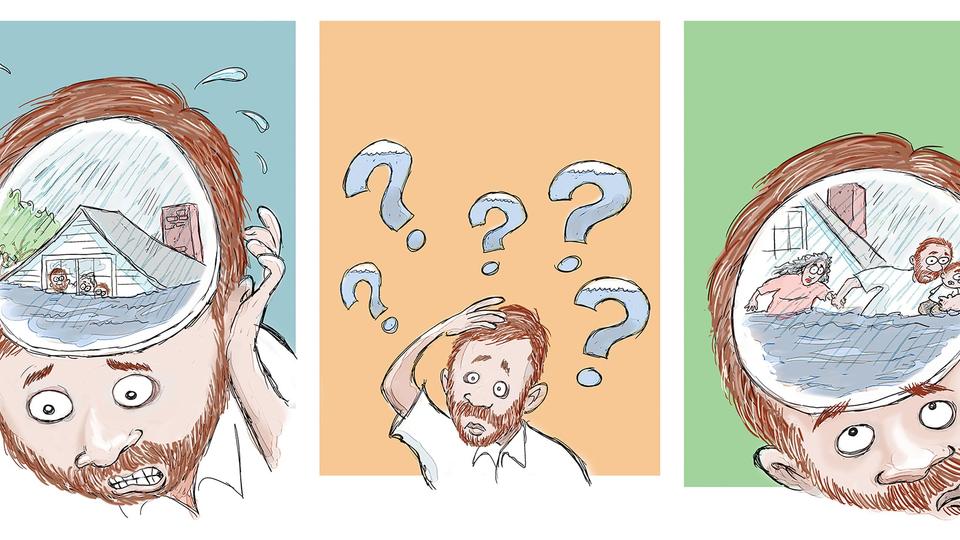

Illustrated by Nick Anderson. Based on an article written by James Weston and Erik Dane.

How Do You Decide To Sell Your Harvey-Drenched Home?

A year after Harvey displaced thousands of homeowners, many are now wrestling with what to do with their beloved, damaged homes. Rice Business Professor James Weston and former Professor Erik Dane offer essential guidance on how to think about this big decision in their article Should I Stay Or Should I Go? Nick Anderson illuminates.

James Weston is the Harmon Whittington Professor of Finance at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University

Erik Dane is a former professor and was the associate professor of management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University

Nick Anderson is a Pultizer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Stocking Up

How rescue and relief workers are drawing on the lessons learned from Hurricane Harvey to prepare for the next big disaster.

By Tracy L. Barnett

How Rescue And Relief Workers Are Drawing On The Lessons Learned From Hurricane Harvey To Prepare For The Next Big Disaster

It was the relief effort watched around the world. As big as Hurricane Harvey was, the human spirit of Houston was bigger: A Texas-sized show of solidarity came through in the aftermath of the hurricane. The number of neighbors helping neighbors — in kayaks, in motorboats, in pickup trucks, in human chains — seemed to break all past records.

And yet gaping holes in the social fabric still affect the daily lives of thousands of people. A year later, nonprofits and grassroots disaster-relief organizations are trying to patch these holes while they prepare for the next disaster — because at this point, Houston has accepted that it’s not “if,” it’s “when.”

Some grassroots groups coalesced spontaneously during Harvey, after Houston’s institutional response became bogged down by the storm’s magnitude. When the streets around the Houston Food Bank flooded, groups like the Midtown Kitchen Collective and the Giving Hub worked to fill the food-delivery vacuum. DIY rescue and relief groups including Recovery Houston and the Cajun Navy operated around the clock without pay, relying on social media networks, fast-paced innovation and pure grit. Meanwhile cash-strapped community organizations like Casa Juan Diego, Boat People SOS Houston and the Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (TEJAS) depended on an influx of volunteers who helped pick up the slack during the storm.

Event planner Kat Creech, who started the Facebook group that became Recovery Houston, marveled at the number of hearts and hands working to help in the days after the storm. As the year wore on and relief efforts turned to rebuilding, however, the numbers dwindled. Creech blames compassion fatigue — and what she calls “survival fatigue.”

“These people are doing everything they can to keep putting one foot in front of another as the rest of the world has gone back to normal,” she says.

Dr. Betsy Escobar, who volunteers at Casa Juan Diego — a Catholic charity that serves immigrants, refugees and the poor — said the center was overrun after Harvey by immigrants who feared detention by Immigration and Customs Enforcement if they went to shelters or the convention center. “FEMA gave us a bunch of cookies, but we have a lot of people who are diabetic so that was not very helpful,” she recalls. Thankfully, the Houston Farmers Market came through with produce, rice and beans. Their next problem was the opposite: They suddenly started getting more help than they could handle. “We got a mountain of clothes, and that’s nice — but we were a little overwhelmed because it was too much,” Escobar says.

This feast-or-famine problem was not exclusive to Casa Juan Diego, according to Balaji Koka, associate professor of strategic management at the Rice Business. On the one hand, Koka witnessed a highly effective response by individuals and small organizations in his area. On the other hand, there were significant gaps in service, something that could be addressed by better coordination among city and county organizations, he said.

“Social media definitely enabled people to become a community with some amount of organization and coordination without any hierarchy,” Koka observed. “But sometimes the same lack of hierarchy would result in one house affected by the disaster being visited by three or four different volunteers, while another house would get lost in the shuffle.”

Rice Business Wisdom surveyed seven community leaders who were involved in Hurricane Harvey rescue, relief and recovery efforts. Here, we distill their collective wisdom about how to maximize our effectiveness in the next big storm.

BEFORE THE STORM

Should I buy a boat or a truck so I can escape or rescue people?

The consensus on this one is a definite NO. Unless you’re an experienced boater with training in navigating floodwaters, you can quickly become a liability, according to Captain Taylor Fontenot with the Cajun Navy.

Instead, find people in your neighborhood who do have boats and trucks and are willing to use them or volunteer them for the rescue efforts, recommended Jonathan Beitler, a volunteer with the ad hoc Midtown Kitchen Collective. In the desperate days after Harvey, the Midtown Kitchen Collective developed ihavefoodineedfood.com, a platform that helped coordinate many of the 300,000 meals distributed by the group, linking thousands of people eager to donate food with the volunteer chefs and service organizations who needed that food. A similar platform could easily be developed to coordinate and connect people who have boats and trucks with people who need them, Beitler said.

Should I stock up on extra canned goods and water so I can have them on hand when the storm hits?

By all means stock up, but be sure you are getting the right things when it comes to giving. The Houston Food Bank is already in preparation mode for this year’s hurricane season, assembling 25,000 disaster boxes of shelf-stable food to have on hand in the event of a mass emergency, said communications director Adele Brady. Lessons learned from last year’s disastrous flooding of the streets around the food bank: The organization is moving towards a hub-and-spokes delivery model, moving resources out to collaborating service centers throughout the city.

What else should I do to prepare?

Take care of yourself and your family first. That way you can be prepared to step in and help with others. Locate your closest shelter and get to know the evacuation route. Have your essentials packed just in case: all family members’ identification, medical records, prescriptions. Pack a “first-day kit” with all the water, food, medicine and anything else you need to survive for a couple of days. Fill your gas tank.

And don’t wait until a hurricane is on the horizon to offer your assistance. Thousands of people still lack adequate housing, furniture, trauma counseling, and other essential needs after Hurricane Harvey. Scores of local organizations are engaged in ongoing recovery efforts, and will be for some time — and they need help.

“After the disaster, everyone wants to help – but maybe think of helping at other times, not just one week after a disaster,” said Escobar. You can sign up with a group like Volunteer Houston, which matches people and their talents with relevant local nonprofits, and develop an ongoing relationship with one of them. You can also register with the group you want to commit to so that they will have your name, contact information and special skills on hand in case of an emergency.

WHEN DISASTER STRIKES

What if I don’t want to evacuate?

Mandatory evacuation is serious, says Fontenot with the Cajun Navy. He and his crew spent valuable hours going back every day to check on people who weren’t ready to leave — time that could have been spent rescuing others. Be aware of what’s going on around you and follow the protocols, he urges.

And be aware that others in your midst might not understand what’s going on — because of language and cultural barriers or disabilities — and that they may be in need of individual help, advised Jannette Diep of Boat People SOS Houston, which has been serving the Vietnamese community of Houston since 1999. An estimated 120,000 Vietnamese immigrants live in the greater Houston area, plus thousands more Southeast Asians of different ethnicities. “These people come from war-torn countries and they’ve already been displaced; they’re afraid of being displaced again,” Diep cautions.

Others aren’t aware of the massive chemical discharges that can and did occur in the industrial corridor of East Houston, said Bryan Parras, director of the Texas Sierra Club and organizer of the People’s Tribunal on Hurricane Harvey Recovery. Or in many cases, they are aware, but they have nowhere else to go. He, like many of his neighbors, suffers from skin rashes and respiratory problems, collateral damage from petrochemical spills.

What should I donate?

Most organizations, like the Houston Food Bank, Juan Diego House and Boat People SOS Houston, will be posting lists of what they need on Facebook or their websites. Check those first.

“When you hear the media talk about how people have lost everything … people inherently start literally bringing everything,” said Creech. “That is wrong in epic proportions — because then you need a warehouse to sort things and hundreds of volunteers to do the sorting. People in a shelter don’t want your dress slacks, they don’t want your stuffed animals, they don’t want your old ceiling fan.”

For those who are in shelters, provide the basics: dry goods, tuna, water, toothpaste and toothbrushes, comfortable clothes, clean socks and underwear. It’s helpful for clothes to be clearly labeled for gender and size for fast processing.

If you’d like to donate used goods to help families with long-term recovery needs, do it during the year, not during the disaster, and give to an establishment that has a warehouse and a staff set up to process and distribute it. Organizations like Helping Hands, the Houston Furniture Bank, and Star of Hope take donated items for distribution among the needy. The city of Houston’s Reuse Warehouse and the Habitat for Humanity ReStore accept reusable building materials and other items that can be used in reconstruction efforts. Some agencies even offer pickup services.

For the civilian rescue crews, bear in mind that they are risking their lives and in many cases their daily bread to save others. Rather than giving your money to big international nonprofits, give directly to the people you see doing the work on the front lines, says Fontenot. They’ll take cash anytime, as well as food, fuel and water during the disaster.

“If that stuff is handled, we can just stay in the water and keep working,” he says.

Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer based in Guadalajara. She aspires to a zero-waste lifestyle but hasn't yet found a substitute for Rancheritos.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Shelter From The Storm

Thirty-three trillion gallons of water had just fallen. How did Angela Blanchard organize a shelter for thousands in a single day?

By Clifford Pugh

Thirty-Three Trillion Gallons Of Water Had Just Fallen. How Did Angela Blanchard Organize A Shelter For Thousands In A Single Day?

With only a few months until her planned departure, Angela Blanchard was looking forward to an informal “Thank You” tour, featuring long appreciation lunches with the colleagues and friends who supported her over 30 years in community development — most recently as CEO of the Houston-based nonprofit BakerRipley.

Then Hurricane Harvey changed her plans.

On the morning of August 29, 2017, Harris County Judge Ed Emmett called Blanchard with an urgent plea. The shelter at Houston’s George R. Brown Convention Center was filled past capacity with residents who’d been forced out of their homes by the hurricane. Another mass shelter needed to be opened immediately. Frustrated by the slow progress of FEMA and the Red Cross, Emmett turned to Blanchard and her staff to get a shelter open at NRG Center.

BakerRipley (formerly Neighborhood Centers) has a long history of helping people recover from disasters. It handled 27,000 new cases after Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans in 2005, when evacuees from that city sought safe haven in Houston. But the nonprofit had never managed a shelter of this magnitude — much less have one open and functioning in a few hours.

A friend warned Blanchard she’d be crazy to take on the task, because if things went badly, she would get the blame. But Blanchard, who had helped open George R. Brown to Hurricane Katrina evacuees — along with assisting in long term recovery after floods and fires devastated Australia and visiting shelters for Syrian refugees in Germany — was confident that her team could pull it off.

Still, as the first buses rolled up, just hours after her conversation with Emmett, who was standing by to welcome the evacuees, she thought to herself, “Please, God, let this work as well as we think it will.”

It did. The shelter took in 850 people within the first 60 minutes. For the next month, 8,500 people from 111 cities in southeast Texas and Louisiana called NRG their temporary home.

“They set up a shelter that I really believe is the model the world is going to use,” Emmett says.

---

How did they pull it off? Blanchard believes that having a strong staff with varied talents to draw upon, along with a willingness to improvise, was instrumental. So were the trusting relationships she’d built long before the storm. “A key ingredient was that I trusted Ed. I knew that he wasn’t going to hang me out to dry. I could throw everything I had at it, knowing that we had shared intentions,” she says.

Emmett’s wife, Gwen, is on the board of BakerRipley and is now its chair, so he was familiar with the nonprofit’s work, although he had only known Blanchard for two years. “Your job in the middle of a crisis is to get through the crisis,” Emmett says. “I was confident (Blanchard) was the right person and that organization was the right organization.”

Likewise, BakerRipley had resources Blanchard could rely on in a pinch. “We knew we could call on H-E-B, Chevron and Shell to help, and they did come, along with many others.” she says. “They had worked with us before and they knew what we were doing would be well run. That mutual understanding of capacity and strength was important.”

In a time of crisis, an effective leader is one who gets people to put the welfare of others over their own self-interest, says D. Brent Smith, senior associate dean for executive education and associate professor of management and behavior at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

“Good crisis leaders, whether they’re in the military or a corporation or a community organization, are good at getting people to identify personally with them and have trust in the agenda that they’re promoting at the time,” Smith says. “They can get someone to set aside their self-interest for that moment.”

“Obviously, the other attribute that I’m sure assisted Angela is the network of resources and relationships that she has accumulated over time,” Smith adds. “Her social capital was absolutely immense. I guess that’s why Emmett called her.”

---

When Emmett called, Blanchard happened to be on another line with the BakerRipley executive team, assessing the condition of the nonprofit’s various centers. Everyone was working from home, since much of Houston remained underwater.

But when Emmett’s call came, they immediately sprang into action. Former Houston Mayor Annise Parker, an executive vice president of BakerRipley at the time, swung by to pick up Blanchard and they made their way to NRG, where they were joined by the other team members who were able to get there. Those who couldn’t make it worked the phones from their homes to get needed supplies.

“In every organization, you have your thinkers and your planners. You have people who are more deliberative and more reflective. They are vital to any organization. If you don’t have them, you’re rudderless,” Blanchard says. “But you also have those people who will run toward the fire or stay at the hurricane. You have to know who they are because you can drop them into any chaotic situation and they can figure out how to act and how to create some order and response out of it.”

Oriana Garcia, now Baker Ripley’s chief of staff, was a prime example, Blanchard says. “I knew Oriana had experience running really large community events for BakerRipley. She was indispensable when it came to laying out the shelter — all the elements of support. And she was willing.”

People came running toward the fire — or in this case, the flood — from multiple organizations. NRG staff helped Blanchard’s team sketch out a basic layout of the facility, arranging the space to include a welcome check-in area, dormitories (separate areas for single women, seniors, families and single men), a kitchen commissary, a lounge area, a dispensary for clothes and toiletries, and a medical care area, as well as a command center away from the main floor. The plan also included a children’s play site and a pet area, as residents are sometimes reluctant to leave a disaster unless they can bring their pets along. The City of Houston Bureau of Animal Control (BARC) set up cages and Barrio Dogs provided volunteers.

But when Emmett gave them an estimate of how many evacuees to expect, Blanchard realized she still needed more volunteers to get the shelter open.

“I walked into the room and said, ‘I need every single person that’s here to find three more people like you. Call anyone like you,’ ” she recalls. (This turned out not to be a problem. Before long, so many volunteers showed up that they had to be turned away because they outnumbered the residents of the shelter.)

By late afternoon, the shelter was ready to open — except for one major problem. There were no cots. FEMA had promised to supply them, but said they had no drivers to deliver them. So Blanchard and her team got on their phones and called everyone they knew who could possibly help. Aztec Rental came to the rescue, sending over an 18-wheeler full of cots. “They drove into the back bay of NRG, and by that time, we had enough volunteers to unload the cots,” Blanchard says.

---

The NRG shelter was no Ritz-Carlton, but Blanchard made it clear from the beginning that everyone who came to stay would be referred to as “guests” or “neighbors.” “I remember distinctly, painfully, after Katrina when people were mistakenly referred to as ‘refugees’ or ‘survivors,’ ” she says. “These are, in fact, our neighbors. Your neighbors. Mine. And for the time of the shelter, they were guests. I think that terminology matters. Words matter.”

Blanchard’s respectful tone permeated the entire operation, recalls Annise Parker. “The one thing that Angela said that resonated all the way through was that these are not your poor evacuees. They should be treated like guests, and that’s going to be our attitude. We’re not doing you a favor. We’re partners in this,” Parker says. “That makes a huge difference in how they feel coming into the shelter and it set the tone for the thousands of volunteers. That was 100 percent Angela. I was astounded by how much of a difference it makes.”

As the first buses began pulling up after 9 p.m., guests found the set-up much like a hotel. After going through security, arrivals were each met with a hug from a volunteer, who took information and then escorted them to a cot that became their “room” during their stay. More than a third of those who checked in had a medical concern, so they were escorted to the clinic and also to the dispensary for supplies.

By 2 a.m., things had settled down, but Blanchard and her team had another crisis: Where was the food to feed the arrivals when they woke up?

An initial supplier couldn’t make it because of high floodwaters, so the NRG employees pulled out all the food they had, like breakfast bars and packaged snacks. BakerRipley staff began sending out calls for help to companies via Facebook and Twitter.

“The next morning I was staggering around like a zombie and I see (H-E-B Houston president) Scott McClelland walking down this massive hallway. And I knew it was going to be alright,” Blanchard recalls. “I’m always glad to see Scott, but this time, I truly was.”

For the first 38 hours, Blanchard, Parker, and BakerRipley executive vice president Claudia Aguirre (who succeeded Blanchard as the nonprofit’s president and CEO) were constantly monitoring the shelter, with occasional naps. “Until we could get enough people organized into shifts, we didn’t want anything to go wrong,” Blanchard says.

Then, for the next 26 days, until the shelter closed on September 23, Parker and Aguirre co-managed the shelter, each working overlapping 18-hour shifts, with Parker as daytime manager and Aguirre as nighttime manager.

“We had lots and lots of agencies working with us, but decisions were made very quickly,” Parker says. “We had very clear lines of command and a lot of folks with a lot of operational experience on the ground from the beginning.”

The staff and volunteers all wore BakerRipley T-shirts, but Parker soon discovered that visiting police units had trouble figuring out who was in charge. So on the second day, she went home and pulled out one of the polo shirts emblazoned with her name from when she was mayor. She noticed that when she wore it, she commanded more respect.

“That little bit of authority made a huge difference,” Parker says. “In essence, for 30 days we had a small city set up. The only difference in running the city of Houston and (the shelter) is I didn’t have to provide three meals a day for the city of Houston. But you have the same issues, and the most important are safety and public health.”

---

Blanchard finally did retire from BakerRipley at the end of last year. But she’ll continue to make disaster assistance her life’s work because, she says, the disasters are only getting worse — and more frequent.

As the shelter population dwindled down after Hurricane Harvey, the nonprofit switched to long-term recovery efforts. Over the past 11 months, BakerRipley has worked with more than 5,500 households and distributed more than $5.2 million in financial assistance for furniture and appliance replacement, emergency and temporary housing, work-related expenses and medical bills. More than 16,000 households have been helped at the nonprofit’s six Neighborhood Restoration Centers through partnerships with the City of Houston and Harris County.

“We have people out here that are still coming in because they cannot make their way through the convoluted bureaucracies,” Blanchard says. Among them is Houston resident Chanel Caston. After the roof of her southwest Houston apartment caved in, soaking all her possessions, Caston made her way to the NRG shelter with her husband and two children, one of whom has autism. “We didn’t have nothing; only the clothes on our back,” she recalls.

They spent most weekdays at the shelter until it closed, leaving on weekends to be with Caston’s mother at a senior citizen’s facility. “Our condition [at the shelter] was A-1 to me,” Caston says. “It’s nothing like home, but due to the circumstances it was wonderful.”

Now she faces a new set of problems because her housing assistance ran out in July and she pays $975 in rent for a one-bedroom apartment to house her family of four. She travels to several food banks to feed the family and is working with a case manager at BakerRipley to secure other basic needs.

“(Harvey) left me in a predicament,” Caston says. “We’re still trying to get back on our feet.”

But Caston has hope for the future. So does Blanchard. Her experience during Harvey taught her that leaders are not always in front — and that moments of crisis tend to bring out the best in most people.

“There’s no joy in the devastation of a hurricane. It’s heartbreaking,” she says. “But there’s an extraordinary satisfaction that happens after disasters — the pure pleasure of working with people when the mission is compelling, the urgency is clear, and you do whatever it takes. And it’s encouraging to see everyone doing all they can to help one another. The generosity of the human spirit.”

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Course Correction

How to bring strategic thinking back into corporate marketing.

Based on research by Ajay Kalra and David Soberman

How To Bring Strategic Thinking Back Into Corporate Marketing

- Most firms emphasize speed over finesse. Both, though, are necessary for marketing success.

- Building a competitive corporate culture is great — unless it saps the company’s efficiency and profits.

- Corporate managers need to do a better job of asking critical questions, doing comprehensive research and synthesizing results.

You’re the regional brand manager for a light beer company based in Houston and you happily dominate the competition. You’ve got the best light beer in America and everybody knows it.

Then you learn that a rival beer company, which for years has sponsored the Dallas slow-pitch softball tournament, no longer has cash to support their signature event. True, it’s not clear that the tournament is the right fit for your brand. But the head of sales tells you he wants to get behind it. So you buy in.

Then reality hits. Those slow-pitch softball players don’t like light beer — and they won’t drink it. Your sales languish. You may be the tournament sponsor, but anyone can see the players are drinking something else. What to do?

If you’re like countless American firms, you declare the sponsorship a success year after year regardless of what is really going on.

Rice Business professor Ajay Kalra joined David Soberman of the University of Toronto to investigate just this kind of mishap. While prevailing wisdom blames marketing failures on CEOs and other senior management, such failures often begin at the bottom and work their way up. This triggers a chain of bad analysis, bad decisions and worse results.

Most brand managers, the researchers found, make decisions by setting market objectives, developing a strategy and implementing it. The results of that strategy are then used to evaluate the next set of decisions to be made.

The problem with this approach is that it leaves out a crucial set of prior questions. What, for example, are the consumer perceptions about the product that may affect their behavior over time? What analysis exists about the competition?

Once brand managers have asked key questions, they need to get the answers. In some cases that may entail a market study or other original research. Over the past half-century, some of the biggest advances in marketing management have to do with data collection and analysis techniques, including focus groups and attitude surveys. Once the research is complete, it needs to be synthesized, and usually presented to a cross-section of people within the firm.

Sounds simple enough. Why, then, do so few brand managers follow this rational sequence before launching a new campaign?

One answer is time. It takes roughly two-and-a-half months for a firm to launch a marketing campaign. Most brand managers, the researchers argue, want to shorten that time as much as possible to stay ahead of the competition. Strategic analysis typically gets short shrift.

When you’re short on time, the pressure mounts. Lacking serious strategic analysis, managers tend to look to their most experienced colleagues for advice. The result: The quality of decision-making depends almost entirely on the quality of advice the manager gets. Maybe she’ll get lucky and find a visionary to guide the team through a thicket of issues. Often, however, she won’t.

Short-circuiting the decision-making process, in fact, often becomes a part of the corporate culture. This happens in part because companies have developed such a culture of rivalry that they are willing to make what are essentially irrational decisions in order to be seen as “winners.”

In 2004, in Scotland for example, Ryanair and EasyJet were engaged in such a fierce competition that the airlines were literally giving away seats for free: great if you’re a customer, but not generally good for business.

All of this points to the need for a serious rethink around strategic planning, research and even corporate culture, Kalra and Soberman say. Speed is important to the planning process, but so too is finesse. Training needs to de-emphasize competition with the enemy in favor of strategies that maximize profits. Instead of relying on what is often half-baked, informal advice from colleagues, firms need to identify sources of expertise at each level of the organization.

To boost this expertise, managers who are too good to fire but not good enough to promote can be moved laterally, allowing them to accumulate meaningful expertise. After all, almost anyone is capable of learning. There is no reason why people — or firms — should commit to repeating their mistakes.

Ajay Kalra is the Herbert S. Autrey Professor of Marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Kalra, A., Soberman, D. The Forgotten Side of Marketing. Journal of Brand Management, (2010). 301-314.

Never Miss A Story