Big Spender

When high prices attract consumers and low prices repel them.

By Utpal Dholakia

When High Prices Attract And Low Prices Repel

This article originally appeared in Psychology Today.

As consumers, we think of high prices as painful and low prices as attractive. However, prices have a powerful informational value that can make this relation invalid. The level of an object’s price embeds and conveys useful information about its quality (or lack thereof) or the quality of the store from which it is purchased.

For instance, if all I tell you about one particular car is that it has an $85,000 price tag, visions of a posh luxury car are sure to dance before your eyes even when no other information about the vehicle is forthcoming. You are unlikely to visualize a hatchback or a cookie-cutter minivan given this $85,000 price point.

On the other hand, if I tell you my lunch today cost just one dollar, you will guess I had a taco or a hot dog from a food truck, not a gourmet multi-course meal.

An item’s price level, by itself, delivers useful, and sometimes diagnostic information about the product. The informational value of price is particularly potent when the item’s price is extreme, either on the high end or the low end. It can work in counter-intuitive ways that make little economic sense.

The case of the bargain basement author

To understand the power of informational value, Consultant Dorie Clark recounts the case of a highly-regarded New York Times bestselling author who was invited to be a keynote speaker at an association’s annual convention. When asked his speaking fees to participate, the superstar author quoted a modest price of $3,000, a fraction of what the association was expecting to hear. Instead of being thrilled at having locked up a top-notch speaker at a price far below the budgeted amount, the event’s organizers started having second thoughts. They wondered whether they had chosen the right speaker and grew concerned about the quality of the speech he would deliver. This adverse reaction occurred because the price was too low! As Clark insightfully advice, “Price is often a proxy for quality, and when you put yourself at the low end, it signals that you’re unsure of your value — or the value just isn’t there. Either can be alarming for prospective clients.”

The highest price point can be the most comforting one

In the late 1990s, when the consumer packaged goods behemoth P&G wanted to introduce the new Olay Total Effects product, the company tested different price levels of $12.99, $15.99, and $18.99 to determine which price would be the most appealing to target customers. They would presumably have made a profit at all these prices. At the low price level, a fair number of mainstream consumers who shopped in grocery or drug stores expressed interest in Olay, but the prestige shoppers who purchased it in department stores were not as responsive. They thought it was too cheap to be in department stores. At the $15.99 price level, the amount of purchase interest from both groups declined. But surprisingly, when Olay’s price was increased to $18.99, both groups, and particularly, the department store shoppers’ intentions to purchase shot up to levels higher than the $12.99 price. More people wanted to buy the same product at a higher price. As Joe Listro, Olay’s R&D manager explained:

So, $12.99 was really good, $15.99 not so good, $18.99 great. We found that at $18.99, we were starting to get consumers who would shop in both channels. At $18.99, it was a great value to a prestige shopper who was used to spending $30 or more [for a similar product]. But $15.99 was no-man’s-land—way too expensive for a mass shopper and really not credible enough for a prestige shopper.

What is striking about this story is that the exact same product was being tested by P&G, yet it was the price level that created such a varying degree of response. The informational value of the $18.99 Olay price lay in comforting the prestige shoppers by signaling the product’s effectiveness, and in making the product aspirational for the mass shoppers, portraying it as an affordable luxury item that they could splurge on. Anything lower was detrimental to the new product’s success.

High prices attract consumers when assessing quality is difficult

As both these cases show, the informational value of price is particularly powerful when the buyer has difficulty in discerning the item’s quality. The keynote speaker’s services were what marketers call an “experience good,” the quality of which can only be evaluated after the experience is complete. Similarly, the Olay Total Effects product was being newly introduced to the marketplace, so consumers did not have a good idea of what to expect.

The main lesson for consumers is this. When a product’s quality is hard to assess, that’s when savvy marketers tend to set prices at a high level to signal that they are selling high-quality items. This is when you should take the time to do research and try to understand what contributes to quality so that you can buy the item with the best value instead of the most expensive one.

Utpal Dholakia is the George R. Brown Professor of Marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Pay Day

Why companies are actually doing investors a favor by not paying dividends.

Based on research by Gustavo Grullon, James P. Weston, Bradley Payne and Shane Underwood

Why Companies Are Actually Doing Investors A Favor By Not Paying Dividends

- The number of companies paying dividends has dropped dramatically in the past 30 years.

- But companies are making net payments — through other types of cash disbursements, including share repurchases — that are as high or higher than they were in the 1970s.

- By shifting cash distributions to repurchases instead of dividends, firms moved towards a policy of minimizing the tax burden on their investors.

“The only thing that gives me pleasure is to see my dividend coming in,” oil magnate John D. Rockefeller once said. Rockefeller wasn’t the only investor to cherish the portion of corporate earnings that companies have historically divided among their shareholders. The dividends a company paid were once the most reliable public demonstration of its financial health. During the dark economic days of the 1930s, federal legislation began requiring companies to conduct business with more transparency. Before that, dividends acted as one of the few visible ways investors could judge a company’s success.

But a dramatic drop in the number of firms paying dividends from 1978 to 1999 has posed a puzzle to analysts who study capital markets. Experts have long believed that the decline in dividend payments reflected the transitory nature of company profits. But Rice Business scholars recently discovered a conundrum: Large firms with higher earnings are the least likely to pay dividends. These companies aren’t crippled by costly external financing, and they don’t need to hoard cash for investment purposes.

So why aren’t they paying out?

Dividend levels differ enormously from company to company. Some of the fastest growing companies, such as internet startups, tend not to pay dividends at all. As these companies swiftly expand, they plow profits back into their businesses. But for older, more established companies, stockpiling profits or funneling them back into the firm may not be the wisest decision. Experts expect more mature, established companies to pay dividend yields above the market average.

Rice Business Professors Gustavo Grullon and James P. Weston, along with Bradley S. Paye, now a finance professor at Virginia Tech, and Shane Underwood of Baylor, decided to approach the puzzle by looking at other forms of paying out. They examined whether net cash distributions to equity holders, including repurchasing shares and issuing stock, have declined similarly — and when they looked at these figures, a very different picture emerged. They found no decline. In fact, they discovered that net payout yields have increased over time.

Their research showed that many firms were positive net payers even if they weren’t paying dividends. And many companies that paid dividends turned out not to be positive net payers. Scholars determined that although dividend payments have fallen, companies are as likely to make net payments today as they were in the 1970s. These results proved consistent across a number of methods of measurement. In fact, the findings suggest that corporations currently distribute more cash to their shareholders than in the past.

The researchers studied payouts by publicly-traded domestic firms with a median age of 16 years. Young firms are expected to have a greater need to save cash than established ones, and since publicly-listed companies tend to be younger and less profitable than they were 30 years ago, researchers expected that the number of companies returning cash to shareholders would drop during this time period. But the scholars found the opposite. They discovered that the number of firms with low retained earnings that distribute cash to equity holders actually has increased. What’s more, they found that firms were shifting cash distributions to repurchases instead of dividends — thereby easing the tax burden on investors who would have paid higher penalties on dividends.

By looking at net payouts — such as repurchased shares and stock issues — instead of just dividends, the researchers came to an entirely novel understanding of payout policy. For example, the fact that firms with relatively low earnings were actually more likely to return cash to shareholders than they were in the 1970s may reflect the loosening of restrictions on repurchases that have facilitated the use of stock buybacks among smaller, less mature firms.

Their conclusions also have major implications for tax policy. Proponents of the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, for example, argued that in the wake of the corporate scandals of 2001 and 2002, firms needed encouragement to return cash to shareholders. The act, commonly known as the Bush Tax Cuts, lowered taxes on dividends and capital gains, among other measures. As the researchers note, proponents believed the legislation would “jumpstart a staggering economy, jolt stock prices upward, and release a cascade of corporate cash into the pockets of upscale consumers.”

But those who made such arguments presumed that firms were less likely to distribute cash to investors than they had been in the past, and that altering the tax code could help reverse this trend. The research suggests otherwise. Firms were just as likely to return cash in 2003 as they were in 1978. A diehard dividend fan like Rockefeller might find himself waiting a long time at the mailbox today for an envelope that never arrives, but investors are still getting payouts — more now than ever before.

James P. Weston is a Harmon Whittington Professor of Finance

Gustavo Grullon is a Jesse H. Jones Professor of Finance at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Grullon, G., Paye, B., Underwood, S., and Weston, J. P. (2011). Has the Propensity to Pay Out Declined? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46(1), 1-24.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Time Warp

Facebook recently invented a new unit of time, the “flick.” What time units will they launch next?

By Jennifer Latson and Andrew Sessa

Facebook Has Created A New Wrinkle In Time

This article originally appeared in the Houston Chronicle

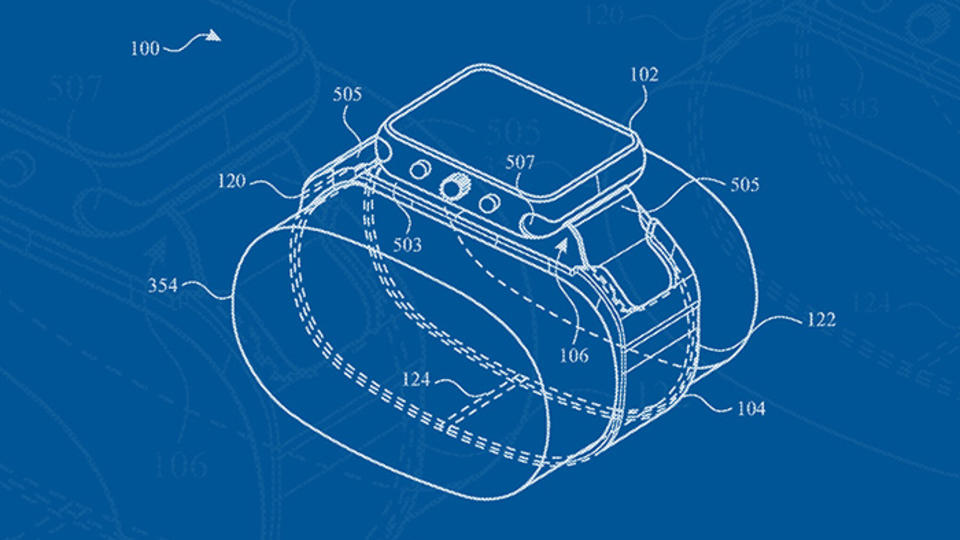

Last week, Facebook launched a new unit of time: the flick, which corresponds to 1/705,600,000th of a second. If you’ve always thought a nanosecond was too short but a second was far too long, this is the increment you’ve been waiting for. But why should Facebook stop there when it could launch an entire time line?

- The friend requant: The time it takes to decide whether to accept a friend request from your 8th-grade frenemy, Amber, who you’re pretty sure just wants to sell you essential oils. Length: Somewhere between a nanosecond and a flick, on average.

- The memute: How much time you have to post your own witty take on the latest viral meme before it becomes stale. Length: The number of flicks it takes Sad Keanu to eat a sandwich alone on a park bench.

- The Facebyte: The time spent crafting exactly the right comment when your freshman-year roommate posts that she has sold her first novel, which must include the word “congrats” (for the balloon effects) and should in no way reveal that you are dreading the debut of what she describes as “Fifty Shades of Grey set in the zombie apocalypse.” Length: About half a memute, plus a few billion flicks to decide between the thumbs-up or the heart emoji.

- The privasec: The interval when you carefully adjust your privacy settings after Facebook revamps them before just giving up and posting your social security number, wedding anniversary and mother's maiden name in your bio. Because, let's face it, you're destined to lose that battle. Length: As long as it takes to say “year-long security breach that exposed the private data of 6 million users.”

- The flack: The period in which it slowly dawns on you that the unexpected message from your college crush was not prompted by his realization that he made a horrible mistake in never calling you after that one party where you totally hit it off — but was in fact a prelude to him asking you to donate generously to your 15th reunion class gift. Length: Way longer than it should have taken. Come on.

- The fluke: The time it takes you to figure out that the story in your news feed about Malia Obama’s addiction to Tide PODS was generated by Russian bots (and reposted by Amber). Length: Much less than a flack, to your credit.

- The flunk: The total length of your Facebook tenure before you decide to disable your account. Alternate usage: The amount of time your account stays disabled before you realize you can’t live without it. Length: Varies, although the former is measured in memutes and the latter in flicks.

Jennifer Latson is an editor at Rice Business Wisdom and the author of The Boy Who Loved Too Much, a nonfiction book about a rare disorder called Williams syndrome.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Energy Boost

What's the forecast for the U.S. energy industry and its effect on our global competitiveness? Looks sunny, reports Rice Business Professor Bill Arnold.

By William M. Arnold

What Is The Forecast For The U.S. Energy Industry And Its Effect On Our Global Competitiveness?

This article originally appeared in The Hill.

The early days of 2018 are a good time to consider America’s energy landscape and how it impacts our broader global competitiveness. The outlook is good.

The shale revolution in the U.S., OPEC’s varied responses, changes in federal regulations, as well as the cost of oil and gas here, relative to the rest of the world, all impact the country’s economy.

These dynamics have been in active play for close to a decade but seem to have reached a “new normal” in recent months.

The implications of the shale revolution are many. It provides an unprecedented level of energy security as U.S. production reaches levels unseen for 30 years and puts us among the top three producers in the world. Politically, this provides some immunity from crises in places like Venezuela and Nigeria.

It also encourages energy companies, large and small, to invest tens of billions of dollars back in the U.S. over countries with less stable business environments. That translates into high-paying jobs and economic growth in places like West Texas, North Dakota and Pennsylvania.

OPEC’s response has been erratic since the collapse of oil prices three years ago. In early 2015, many U.S. producers bet, to their misfortune, that OPEC would cut its own production to stabilize prices above $70 a barrel. Instead, OPEC let market dynamics rule and prices collapsed by more than 70 percent into the high $20s.

More recently, OPEC and other major producers like Russia agreed to cut production, and they showed discipline in the implementation. That helped drive prices to about $60 in the U.S. and $65 outside the U.S. (the “Brent” market). The $5 difference between oil in the U.S. and the rest of the world adds to our competitiveness as the price of refined products plays out in the cost structure of economies.

While oil prices have rallied, U.S. natural gas continues to be cheap (aside from Arctic weather spikes) because of abundant supplies, new technology, infrastructure, ease of market entry and available capital. This has led to the rapid-paced closure of uncompetitive coal-fired power plants across the country. A consequence of this has been the drop in America’s carbon dioxide emissions to a 20-year low.

Many of the nations with which we compete in Europe and Asia pay two to three times, or more, for the clean-burning fuel that provides residential, commercial and industrial power. America is now exporting natural gas that supports the independence of vulnerable countries like Lithuania, which had been dependent on Russian supplies until they built a facility to import liquefied natural gas.

Cheap natural gas is also having a dramatic effect on the nuclear power industry. Many U.S. facilities were built decades ago and are at the point where they would need major refurbishment. But in the current price environment, many of these plants are slated for closure instead of renovation, which would cost tens of billions of dollars. New facilities are few and have been subject to dramatic cost overruns.

Wind power has emerged as a growing source of energy, at times providing a majority of power supplied in Texas, home to the greatest concentration of producing turbines in the U.S. The prospect for offshore wind, which has been a factor in Europe for many years, adds to the potential.

Subsidies are still an important economic component and interstate transmission is a challenge. Solar has grown exponentially but from a very small base, with sharply declining costs, but has had less widespread impact.

The Trump administration has attacked regulation broadly, especially in energy. The recent proposal to open nearly all offshore areas to oil and gas drilling — in Alaska, the Eastern Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic and Pacific coasts — is a dramatic example.

There will be political and environmental challenges. The lease sales would run between 2019 and 2024, when prices for oil and gas are difficult to foresee.

Previously, President Trump announced he would abandon the Obama administration’s Clean Coal Plan that had already been suspended by the U.S. Supreme Court. In contrast, the Department of Energy has proposed initiatives, now pending, to provide financial support to coal and nuclear because of their reliability of supply for power generation.

Also, disputes over regulation of fracking on federal lands tipped in favor of state regulators. And the Interior Department is rolling back offshore drilling safety rules in light of the industry’s adoption of new safety practices.

The recently signed tax overhaul drops the corporate rate for all industry. Ironically, though, companies like Royal Dutch Shell had to take billion-dollar financial charges in the fourth quarter of 2017 because this impacted the value of tax losses that they carry forward. But the dramatically lower federal taxes will favor U.S. production as companies decide on future portfolio allocations.

The convergence of these seemingly diverse factors combine to provide a fruitful basis for strength across the U.S. economy as 2018 gets underway.

Bill Arnold was a professor in the practice of energy management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Mood Swing

Our emotions affect our decision making more than we know.

Based on research by Jennifer M. George and Erik Dane

The Hidden Role Of Emotion In Decision Making

- Passing moods and deep emotions are both integral to the quality of our decisions.

- Affect — the moods and emotions that are experienced — drive decision making

- Regret is a powerful factor in confronting potentially difficult decisions.

You’re a senior executive and you have to make a major decision. What’s your mood? The answer wields more power than you may guess.

The emotional environment surrounding business decisions is usually dynamic, and often turbulent. By its very nature, decision-making in large organizations is a messy, complicated and ambiguous process. In this whirl of activity, emotional states can affect decisions even more dramatically than the decision-maker may know. Whether he or she realizes it or not, emotions ranging from rage to pleasure at someone else’s discomfort can indirectly lead to huge financial gain or devastating loss.

In a recent study, Rice Business Emeritus Professor Jennifer M. George and former Professor Erik Dane analyzed the scientific literature showing how emotion and mood — i.e. how an individual feels — influence decision-making.

Let’s say, for example, you are one happy executive. Cheerful people make the best decisions, right? Not necessarily, George and Dane found. Research suggests that happy people believe positive outcomes are more likely than negative ones. So cheerful decision-makers often overestimate the likelihood of a positive outcome and underestimate the chance of a negative one. And that’s not necessarily a happy thing.

In a study of foreign exchange traders, for example, participants who were in a good mood were overall less accurate in their decision-making, lost money and took unnecessary risks compared to both those in a control condition and those in a bad mood.

Another widespread assumption: The more complex a situation, the more thoroughly an executive conducts research prior to making a choice. But moods can also affect how we engage and understand research. George and Dane found that decision-makers in a negative frame of mind tend to be more focused when facing a high-risk situation. Decision-makers who feel more upbeat tend to be less focused in their information search.

Anger, on the other hand, can undermine good decisions. People who experience anger, the researchers found, are prone to take greater risks. Anger can, though, work wonders in helping to evaluate others, especially when those evaluations are less than positive.

Some of the most anti-social emotions, in fact, may bolster good decision-making. According to two studies, schadenfreude, or “feelings of malicious joy at the misfortunes of others,” prompted subjects to make more practical choices than they did when feeling happiness or sadness.

And in many cases, mood and decision-making are circular. Consider a manager forced to choose between two very bad product options. In one study from 2000, people were asked to choose between two low-quality alternatives, one of them lower-priced and the other a somewhat better product, though still low quality. Facing two miserable choices made the subjects so despondent that they chose the higher-quality option — but simply as a response to emotion.

The role of regret in decision-making has inspired especially broad research. In some cases regret surges even before a decision is made. In other cases it’s a consequence of the decision process itself.

Either way, regret can have profound implications in the business world. Let’s say that a manager is faced with a series of difficult choices. Research suggests that people feel more regret over a choice that goes bad than over making no choice at all. Acting on this dynamic, the hypothetical manager may delay important choices until it is too late to make a difference.

While the role of emotion in decision-making is vast, George and Dane note that it’s also under-researched. For the business world, more study is needed on the role of emotion in complex business environments. Far from being frivolous, emotion, it turns out, is the quiet engine powering every choice we make — not to mention those choices that others make to hurt or help us.

Jennifer M. George is the Mary Gibbs Jones Professor Emeritus of Management in Organizational Behavior at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Erik Dane is a former professor and was the Jones School Distinguished Associate Professor of Management (organizational behavior) at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: George, J.M., & Dane, E. (2016). Affect, emotion, and decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 136, 47–55.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Lonely at the Top

Star performers earn higher pay and receive faster promotion. But these perks tend to have a social cost.

Based on research by Jing Zhou, Elizabeth M. Campbell, Hui Liao, Aichia Chang and Yuntao Dong

Star performers earn higher pay and receive faster promotion. But these perks tend to have a social cost.

Every business wants the best and the brightest. Once they spot these top talents, corporations typically lavish time and money to hire, train and groom them for success. Life should be simple for the lucky hires.

But if you’ve ever watched crabs trying to climb out of a bucket, you know it’s not. The closer any one crab gets to the top, the more likely it is to evoke the spite of its fellow crabs, who will try to drag it back down.

A study coauthored by Rice Business professor Jing Zhou shows that while high performers bring substantial value to their organizations and workgroups, they also attract inordinate social attention — not all of it positive. The findings are especially important because high performers are less likely to stay with their organizations or sustain exceptional success if their social experiences at work are difficult.

And for many top performers, that’s clearly the case. A full 30 percent of top corporate employees leave their firms within one year, according to Zhou and coauthors Elizabeth M. Campbell of the University of Minnesota, Aichia Chuang of National Taiwan University, Yuntao Dong of the University of Connecticut and Hui Liao of the University of Maryland. For years, the scholars write, employers assumed that their workplace stars were either too bored or too restless to stay put. Now research shows that they leave their jobs because of how they’re treated.

To add to this body of research, Zhou and her colleagues conducted a time-lagged study of 414 hair stylists working for 120 salons in northern Taiwan. Why salons? Stylists, the researchers explain, work in open spaces where their peers can see their performance. And because salons are magnets for employee chatter, Zhou’s team could easily monitor interactions there.

What they found was a subtle and stressful power struggle. On the one hand, as high performing stylists improved their job performance, peers saw them as beneficial to their own images. Less talented workers attached themselves to rising stars, hoping the reflected light would also illuminate their prospects.

But even as the top stylists reaped attention and support from their peers, they were perceived as threats. Whenever the best performers got attention, those around them became jealous.

This finding soon led to a second discovery. The colleagues of the high performers weren’t just jealous; they were actively working to undermine the high performers at the same time they were supporting them.

The toll was great, Zhou writes. It would be one thing if high achievers knew their colleagues either admired them or hated them. But the unspoken tug-of-war between support and sabotage caused a unique strain.

In such toxic environments, the high achievers found work more stressful than their less-accomplished colleagues. This, the researchers believe, likely accounts for why so many top performers leave their jobs for other opportunities.

To a certain extent, Zhou and her team say, such stress is hardwired into the workplace. Employers value workers who function as a team. At the same time, they prize individuals whose achievements stand out from the group. With such contradictions, the particular stress that plagues high performers may be inevitable.

So what’s the lesson? True, star performers earn higher pay and receive faster promotion. But these perks come at a social cost. No wonder achievers struggle to maintain top performance levels and typically leave their firms sooner than their coworkers.

In general, employers need to closely attend to their employees’ wellbeing, taking into account the unique social stresses that affect high performers. Ideally, managers can craft environments in which the top achievers — and their more average associates — all feel welcome.

According to Zhou and her colleagues, such harmony isn’t just about keeping a few divas happy. Undermining and jealousy, their findings show, actively drive off top performers. It’s only natural for crabs to claw their fellow crabs back into the heap. So it’s up to managers to protect their best performers — or end up with a bucketful of motionless crustaceans.

Jing Zhou is the Mary Gibbs Jones Professor of Management and Psychology in Organizational Behavior at the Jones Graduate School of Business of Rice University.

To learn more please see: Campbell, E.M., Liao, H, Chuang, A., Zhou, J., & Dong, Y. (2017). Hot shots and cool reception? An expanded view of social consequences for high performers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(5), 845-866

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Short Circuit

Businesses like technology as a way to reach audiences quickly and nimbly. What could go wrong?

By Utpal Dholakia

Businesses Like Technology To Reach Audiences Quickly And Nimbly. What Could Go Wrong?

This article was originally posted on LinkedIn.

I just finished writing a paper called, "All's Not Well on the Marketing Frontlines: Grasping the Challenges of Adverse Technology–Consumer Interactions."

There are far too many technology-driven phenomena that are gathering like storm clouds on the horizon that mainstream marketers are not paying sufficient attention to. There are many examples of this, whether it is the rise of technology-enabled retail fraud by consumers, consumers’ resistance to using self-service technologies and cashless payment methods, the insidious effects of fraudulent negative reviews and social media flare-ups by customers on businesses, the negative effects of consumers' low attention spans and distraction because of smartphone use, survey taking by professional respondents, and the list goes on and on. So I wanted to write about this issue.

Here's the paper's abstract.

The prevailing marketing worldview is one of technology optimism, which holds that consumers and marketers are influenced by technological advances in positive ways. In contrast, the central thesis advanced in this paper is that at the organizational frontlines where marketers inform, persuade, observe, and co-create products and services with customers, technology commonly produces unforeseen and unexpected effects on customers with significant negative implications for marketers, the so-called “Adverse Technology-Consumer Interactions” or ATCIs. Marketers play an instrumental role in producing or exacerbating an ATCI, yet have few incentives to fully investigate the underlying reasons, understand its scope, or find solutions. Academic researchers, on the other hand, are uniquely poised to identify ATCIs, investigate them in-depth by considering their industry-wide import, develop appropriate theoretical frameworks, and design and test solutions to alleviate their effects. These ideas are developed through the detailed consideration of two ATCIs, falling response rates to customer surveys, and customer reactance to frequent price changes. Promising research opportunities are highlighted in each case.

The entire paper is available here.

It's very much work in progress, so I would love to hear thoughts and criticisms.

Utpal Dholakia is the George R. Brown Professor of Marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Royal Favor

What happens when the highest leader in the country comes to call?

Based on research by Douglas A. Schuler; Robert E. Hoskisson (George R. Brown Emeritus Professor of Management), Wei Shi and Tao Chen

What Happens When The Highest Leader In The Country Comes To Call?

- In China, where information on public companies is scarce, a visit from a high official is a coveted signal of government confidence.

- Such visits result from complex, longtime bonds between the state and the firm.

- Depending on the status and location of the host company, some high-level visits have more market value than others.

For a Chinese business owner, when the sixth Premier of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China inspects your factory, it’s likely to be one of the biggest days of your career: the modern equivalent of a royal handshake.

It may signal that your firm is the kind of enterprise the Chinese government supports. It may mean your firm’s sector holds strategic importance for the most populous country on earth. And if your business or economic sector is suffering a global downturn, it indicates that one of the world’s most powerful states supports your efforts.

Surprisingly, though, there’s little literature about the interactions that make such high-profile appearances happen. Does a visit from the Chinese premier or president mean more for some types of firms than for others? Is it more important for a privately held firm than for a state-owned enterprise? And is it more or less significant for a firm in parts of China not normally exposed to such attention?

Rice Business Professor Douglas Schuler and Emeritus Professor Robert E. Hoskisson joined Wei Shi of Indiana University’s Kelly School of Business and Tao Chen of Nanyang Business School in Singapore for a close look at high-level visits and their implications. To conduct their research, the team first combed the Internet for accounts of such visits. Then they did a deep dive into reports of 84 visits by Wen Jiabao, Chinese premier from 2003 to 2013, and Hu Jintao, Chinese president from 2002 to 2012, to study the impact of these visits to firms on the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

Official visits, the team found, largely took place in the context of previously existing relationships between managers and government representatives. And though the visits ultimately occurred after senior government officials requested them, advance work always came first. Curiously, the researchers found, these visits weren’t necessarily designed to influence government policies. Instead, they were a continuation of relationships that were already flourishing.

In China, government looms large in business, and information about the health of a given firm may be opaque. So government visits send a message of assurance, especially to investors. That said, the researchers found that the impact of a high level government visit varied, depending on factors that include the firm’s ownership status and even its location.

The researchers found that a visit had the greatest impact on stock prices of firms in provinces not known for economic development. They found a similar positive effect from visits to privately-owned companies, as opposed to public companies, which are mostly government-owned but publicly traded.

While China’s government has a direct interest in propping up state-owned businesses, a visit to a privately-owned business telegraphs its willingness to stake its reputation on that company. It may also suggest that firm managers have a personal government link, worth its weight in gold in Chinese business.

Political connections do enhance a company’s appeal. But for the Shanghai stock market, a high-level visit to a company that’s not politically connected may be even more impressive. It signifies a scrappy business that has overcome ordinary obstacles and been recognized by the premier or president strictly on its merits. Investors around the world, it seems, still love a rags to riches story.

Douglas A. Schuler is an associate professor of business and public policy at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Robert E. Hoskisson is the George R. Brown Emeritus Professor of Strategic Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

For learn more, please see: Schuler, D.A., Shi, W., Hoskisson, R.E., & Chen, T. (2017). Windfalls of emperors’ sojourns: Stock market reactions to Chinese firms hosting high-ranking government officials. Strategic Management Journal, 38(8), 1668-1687.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Team Players

Why fighting workplace discrimination of gay, lesbian and bisexual employees boosts business.

Based on research by Michelle "Mikki" Hebl, Eden B. King and Charles L. Law

Why Fighting Workplace Discrimination Of Gay, Lesbian And Bisexual Employees Boosts Business

Being gay, lesbian or bisexual in the workplace often means facing choices that are deeply unfair. Choose to come out and risk being stigmatized. Hide your orientation and prepare for a career weighted with the immense stress of secrecy. Theoretically, there are good reasons for businesses to embrace a workforce with diverse sexual orientations. First, much workplace discrimination is illegal, and litigation is pricey. More importantly, disdaining 5 to 15 percent of your workforce (the estimated percentage of the workforce population who are gay, lesbian or bisexual) means lagging behind the competition in the ability to recruit and retain top talent. But in reality, the legal protections prohibiting discrimination against employee’s sexual orientation are often limited and what should be the rational business choice isn’t always made.

In an article published in The Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Rice Business professor Michelle "Mikki" Hebl explores the gamut of workplace challenges for gay, lesbian and bisexual workers. Misconceptions about these employees, she found, are still widespread. First of all, employers and coworkers who stigmatize homosexual or bisexual employees often misunderstand their orientation as a choice. The subsequent treatment based on this misinformation can be viciously destructive.

Another common misperception is that sexual orientation can be easily concealed. To the contrary, many gay, lesbian or bisexual workers are actually outed by co-workers, Hebl notes. Because of this possibility, gay, lesbian and bisexual employees often spend an inordinate amount of their work time and energy simply managing their coworkers’ response to their sexual orientation.

And while some people characterize sexual orientation as simply a political issue, those who are gay, lesbian and bisexual employed in a toxic workplace are often not seen simply as undesirables. They can be considered actual threats, their sexual orientation capable of somehow altering the identities of fellow workers. In some cases, associations with HIV and AIDS can lead to gay, lesbian and bisexual workers being treated as physical risks.

Because of these obstacles, many workers are forced into painful choices at work. Do I put my partner’s photo on my desk? Do I mention my weekend plans?

To reduce this burden on productive workers, Hebl writes, businesses should codify their formal rules about managing harassment. Informally, companies need to create a culture in which people of different sexual orientations are supported rather than punished for their sexual orientation.

But companies should know this road won’t always be easy. Some workers will balk at a more diverse environment. The existence of clear policies, moreover, doesn’t guarantee that subtle forms of discrimination won’t take place. But the consequences of not establishing policies are considerable, including litigation and high turnover rates.

In the best of all worlds, the burden of change should not be on the gay, lesbian and bisexual workers themselves. But it’s not a perfect world, so Hebl also proposes strategies to help employees maximize workplace acceptance.

These days, evidence suggests that in some cases, disclosing one’s sexual orientation has benefits. Especially in supportive organizations, it often makes sense for people to reveal their sexual orientation after a period of time and with the support of other employees.

At the same time, Hebl notes, employees may be likely to bully gay, lesbian and bisexual employees whose orientation is the only thing that’s is known about them. Thus, gay, lesbian and bisexual workers face a challenge well-known to other minority employees: delivering exceptional work and displaying exceptional character in order to attempt to allay discrimination.

From an institutional perspective, employers can support their individual gay, lesbian and bisexual employees in myriad ways. Companies can create a welcoming culture by offering same-sex partner benefits. Anti-discrimination policies, frequently voiced, send a message of safety to gay, lesbian and bisexual employees. Such measures require both awareness and real commitment, but the extra efforts pay off well beyond the day-to-day business of hiring and retention. They also encourage open-mindedness, creativity and commitment – and in the end, a more competitive work product.

Michelle Hebl is the Martha and Henry Malcolm Lovett Chair of Psychology at Rice University and a professor of management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

For more information please read: Hebl, M., King, E. & Law, C. (2007). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual issues at work. In S. G. Rogelberg (Ed.), Encyclopedia of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 264-266). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Movable Feast

Eating healthy can be difficult: A Rice Business alum may have a solution.

Eating Healthy Can Be Difficult: A Rice Business Alum May Have A Solution

This article originally appeared in the Houston Chronicle.

Dustin Windham's at the grill on the roof of Houston House apartments, watching Gulf Coast shrimp turn perfectly pink.

It's Wednesday night. As he cooks, his broad-shouldered silhouette framed against the lights of downtown high-rises, a table of guests, most meeting for the first time, share stories about Harvey. Waiting for the shrimp, they look over a spread of roasted organic sweet potatoes, guacamole made from scratch, a cole slaw of fresh purple cabbage and shredded carrots. And plenty of local beer and wine.

If Windham had his way, this is how we would eat every night, all over the city.

It's what he learned to do when he served in the Peace Corps in Azerbaijan. Used to the wall-to-wall abundance of the estimated 38,000 supermarkets in the U.S., he was forced to eat there in a new way.

That's because there weren't any supermarkets. Instead, he says, everyone went about once a month to the bazaar for staples, and the rest of the time picked up what they needed from the produce stand or the butcher shop. Walking home from work, Windham would stop for a few ingredients — some fish, some seasonal vegetables, some baked-that-day bread — and then go cook, usually with friends. "Most Americans don't get that opportunity," he says, "but I learned that it's a better way to do it."

He lost 30 pounds, and he had an idea: Why can't we create that opportunity in Houston? Why can't we eat like that here?

It's a city that could stand to lose a few pounds itself. Almost 66 percent of Texans are overweight, nearly 28 percent obese. According to Roberta Anding, a dietitian and professor at Baylor College of Medicine and Rice University, food-related diseases plague Harris County: The rate of diabetes here is higher than the national average, and it's even worse for people of color; 70 percent of adults surveyed recently by the Houston Health Department take medication for high blood pressure.

Harris County also has one of the highest death rates among the most populous U.S. counties from obesity-linked cancers.

"We have a link between the amount of produce on your plate and disease," Anding says. Meanwhile, the average Texan gets just 1.6 servings of fruits and vegetables a day (The U.S.D.A. recommendation is 5). Forty percent of Texans report eating less than one serving a day. Anding says, "We have a crisis of diet."

And it's a complex crisis, compounded by many other factors, none of them simple to solve in and of itself. One is a basic lack of access to those fruits and vegetables. In 2015, the Chronicle reported that as many as 500,000 Houstonians live in "food deserts," defined by the absence of a supermarket in a one-mile radius. Calories have to come from somewhere, though, and they tend to be found at corner and convenience stores and fast food restaurants — where processed foods are most readily available.

Another is education. Even if you can access fresh fruits and vegetables and fish and lean meats, you have to know how to cook them when you get home. It is not self-evident what to do with a beet.

And another is time. "Parents are busy," says Dr. Faith Foreman, the assistant director of the Houston Health Department. "They're trying to get kids to school, trying to do homework, get dinner, and they start all over tomorrow. It's tempting to hit McDonald's on the way home. It's easy to do that."

These factors lead to a sad conclusion: Our cities are filled with people who aren't eating — and therefore aren't feeling — all that well. "It's a complex problem," Foreman says, "and it requires a complex response."

What cities tend to do, says Doug Schuler, an assistant professor of business and public policy at Rice University, is identify what he calls "supply-side" and "demand-side interventions." You can try to change the foods that people want or change how they get it. In Houston, these interventions range from education programs in elementary schools to shopping tours to city-backed loans like the one Pyburn's Farm Fresh Foods received in 2014 to develop a store in OST/South Union, a food desert.

But even then, consumer behavior is hard to impact.

Six months after that Pyburn's opened, a survey conducted by the Health Department found that there wasn't an increase in the amount of vegetables, whole grains, fish and other seafood that residents purchased there.

"We didn't see much change," says Beverly Gor, a registered dietitian who works for the city.

The same was found to be true in New York City, where a new supermarket developed in a food desert in the Bronx didn't change consumer behavior, either: "The neighborhood welcomed the addition, and perceived access to healthy food improved," concludes Margot Sanger-Katz. "But the diets of the neighborhood's residents did not."

Time, education, access and consumer behavior: Windham wants to provide another intervention, albeit from the private sector, that could help Houstonians with all of these. In 2015, with business partners Michael Powell, Jamal Ansari and Kelly Windham, he founded Grit Grocery.

Windham says he's not a foodie, but Grit Grocery is kind of a foodie's dream. It's a farmers market on wheels, a bodega that parks on your block, stocked with fresh produce and proteins as well as local pasta, cheese, honey, bread and more.

It attempts to replicate for a low-slung, far-flung city pockmarked with food deserts the experience that Windham had in Azerbaijan.

Grit first rolled out in five Houston neighborhoods — downtown, EaDo, Midtown, Museum District and Magnolia Grove — parking in the evenings near apartment buildings when residents were getting home from work. And it was a hit. "It made it easier for me to cook," says Megan Sip, who lives in EaDo and shopped at the truck near her apartment by BBVA Compass Stadium.

"It became a nice community aspect, too," she says. "I'd meet other neighbors out there. It's almost like a watercooler at the office."

Now, while the original truck still makes occasional appearances, Windham is looking to finance through an equity crowdfunding campaign a fleet of trucks, which he will need to match the scale of his ambition — and the scale of this city. Eventually, Grit will also be coupled with a mobile app that will let customers order easy-to-cook preset "meal bundles" that can be tossed in a pan with some olive oil and will include a feature that helps them organize dinner parties.

It's slow food meets high tech.

Already, he has the support of customers like Sip, who says she wants to invest, and Mayor Turner, who calls it a "tremendous opportunity" to create more access and sees an intervention like it as crucial to his Complete Communities initiative.

Foreman says, "It's definitely an opportunity not to solve, but reduce, food insecurity in food deserts. They're on the right track."

Grit Grocery comes at an interesting time. As food-delivery services like Instacart and meal-kit ones like Blue Apron increase in popularity, supermarkets are changing — they're being forced to. In "Grocery: The Buying and Selling of Food in America," Michael Ruhlman traces that change. There might always be Targets and Walmarts — the American version of the bazaar — but many supermarkets have become less super, smaller, focusing less on processed foods and more on fresh produce and proteins.

"Our generation," says Windham, "is learning how to interact with food again. We're recognizing that food preferences are changing."

Now that Amazon has purchased Whole Foods, this change might become only more accelerated. One of Ruhlman's sources, the co-CEO at Midwestern supermarket chain Heinen's, predicts that supermarkets will continue to shrink in size: "If Amazon has its way," he tells Ruhlman, "that stuff in the center of the store will all be delivered to your door. And we'll go back to the old days, where it's all specialty stores."

How small with they shrink? How special will they be?

Windham's betting that it might be as small as a single truck, parked in the right place, providing the right few things at the right time. Maybe that will help the city with food deserts, with diabetes and high blood pressure, with obesity.

"You can have convenient and healthy," he says.

But there's also a reason he named the company "grit." He knows that addressing all these problems isn't going to be easy.

Never Miss A Story