As You Like It

Marketing methodology helps marketers group customers by geography, psychological profile — and desire.

Based on research by Vikas Mittal, Rahul Goving and Rabikar Chatterjee

A Mathematical Model Groups Like-Minded Consumers In Geographic Areas — Close And Far

- For national retailers, a new model shows how to satisfy consumers based on their psychological preferences and geographic location.

- Managers can use this model for better efficiency in their efforts to meet customer needs.

- The model can also give insight into the preferences of like-minded individuals with shared socioeconomic or demographic characteristics.

Will the Jetsons be the reality of the Millennials’ middle age? After all, videoconferencing is already the norm thanks to Skype and Facetime. Drones deliver our packages. Amazon owns Whole Foods, so pressing a button for breakfast might not be far off. As science turns fiction into reality, major retailers from Amazon to Wal-Mart to Kroger need to stay attuned to consumers if they want to stay relevant.

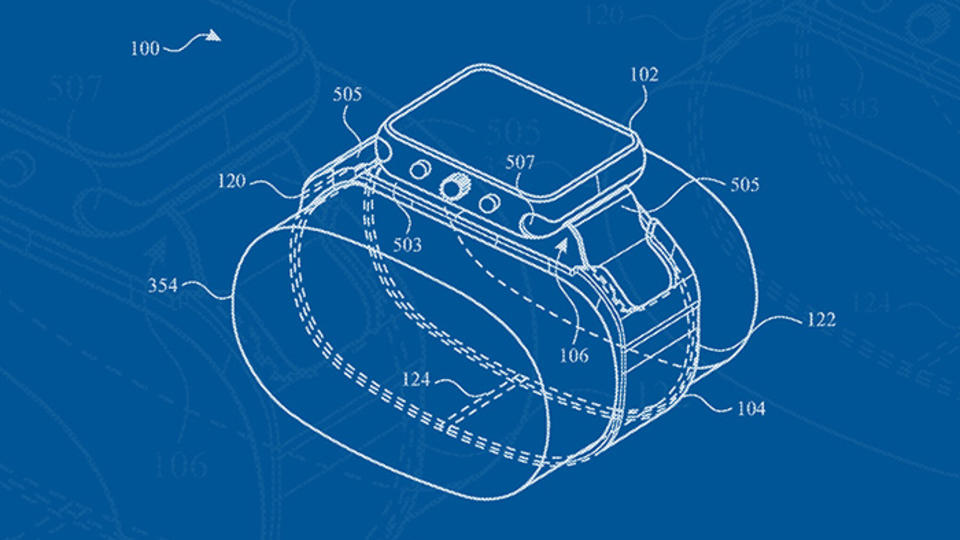

From Sydney to Pittsburgh to Houston, researchers are developing new tools to adapt their strategies to local demands. Rice Business Professor Vikas Mittal collaborated with colleagues Rahul Govind and Rabikar Chatterjee to create such a tool, which they call Spatially Dependent Segmentation (SDS).

Over the years, marketers have segmented customers either based on geography or their psychological beliefs. In one segmentation model, people living in the same zip code are classified as belonging to one segment (e.g., urban or rural). In another approach, customers are classified according to similar beliefs (such as prioritizing price or prioritizing service). The SDS approach does something different: It simultaneously considers consumer psychology and geographic location.

First, the scholars gathered multiple observations about consumer attitudes and needs in each area under analysis. Next, they incorporated estimates that group together similar units into spatially contiguous market segments. This allowed them to estimate consumer satisfaction levels in market segments that were spatially contiguous.

Developing market segments around concentrations of consumers with similar values, culture, and socioeconomics helps big retailers pinpoint ways to satisfy consumers at individual stores, even in very different neighborhoods. For example, big retailers no longer need to view all rural customers through the same lens. By clustering areas with similar consumer profiles, retailers of all kinds can more accurately choose products, services, and pricing, as we`ll as provide training to employees and enough parking for customers at individual stores. For larger retailers, the improved precision makes managing a range of stores less cumbersome. The scholars’ model neatly improves efficiency while permitting better response to consumer demand.

While Mittal and his fellow researchers measured satisfaction of like-minded, neighboring consumers, they noted that their new methodology could apply to shopping scenarios beyond brick and mortar. As shopping moves online, for example, retailers can use this information to make recommendations during live online searches. Their model can also shed light on the tastes of like-minded individuals who live in very different communities.

As the reach of retailers continues to globalize and technologies to evolve, it’s easy to imagine the SDS model helping map regions for drone deliveries. It could also help big retailers spot interpersonal and other links between consumers in given areas. And it could shed light on how and why electoral voting patterns differ across regions and socio-economic groups. Adapting marketing and management strategies to specific stores and their customer base can helps ensure that each person who puts in a breakfast order finishes their bacon and eggs (or kale and quinoa) fully satisfied. Satisfied consumers are loyal customers — the secret to long-term success.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing and Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Govind, R., Chatterjee, R., & Mittal, V. (2017). Segmentation of Spatially Dependent Geographical Units: Model and Application. Management Science. 1941-1956.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Found In Translation

Rice Business' Dean Peter Rodriguez on the power of presenting scientific research in plain language so important ideas are accessible to all.

By Peter Rodriguez

How To Get Ideas From The Ivory Tower To The Public Good

Within the walls of academia, research is cherished and revered, the genuine ‘coin of the realm’ for any serious scholar. Outside the walls, research often appears more like a dalliance, the luxurious hobby of the academic’s lifestyle or the abstruse and unproductive exercise of impractical but well-funded scientific minds.

The failure of academic leaders to communicate the fundamental honesty, rigor and power in great research is our most humbling marketing failure. It keeps us up at night. And it keeps the good stuff, the scientific wisdom, the very hard-won stuff, out of reach for so many who really need it. Now, more than ever, the value of science and of proven research and scholarship needs to be smartly and widely shared.

Some like to water down the complexity of scientific studies to make it palatable and less intimidating. But adding sugar to the medicine steals the integrity of scientific processes and turns professors cold to the process. As a result, academics too often seek only their own kind when sharing successful research.

We can do better, by working hard to craft well-written, honest and authentic pieces on the best research done by scholars at Rice. I am immensely proud of the engaging, brief and refreshingly smart pieces that follow in this inaugural print edition of the best of Rice Business Wisdom. There’s nothing more gratifying to a professor than knowing they helped make someone smarter — and through these works on our research, we can.

On behalf of all my colleagues at Rice, and scholars everywhere, I hope you will read, enjoy and share them widely.

Peter Rodriguez is a Professor of Strategic Management and the Dean of the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Net Worth

What you need to know about net neutrality.

By Phil Shook

What To Know About Net Neutrality

After months of public debate, the FCC voted on Thursday, December 14, 2017, to repeal Net Neutrality, the Obama-era rule requiring Internet service providers to treat all Internet data equally, and not charge differently based on user, content, website or similar variables. The decision could transform how millions of Americans get their online information and how much they pay for it.

The vote pitted telecom giants like AT&T and Comcast against powerful tech companies like Facebook and Google as well as consumer and Internet activists.

Spearheading the repeal effort were President Donald Trump and Ajit Pai, his appointee to head the FCC, who argued that repeal would spur Internet growth and innovation, and is essential to a free Internet. It’s a case that AT&T has made for more than a decade. “Why should they be allowed to use my pipes?" Ed Whitacre, the company’s former chairman and CEO, argued in 2005. "The Internet can't be free in that sense, because we and the cable companies have made an investment and for a Google or Yahoo or Vonage or anybody to expect to use these pipes free is nuts.”

Repeal opponents, however, argue that ending net neutrality will allow telecoms to levy different rates on different types of Internet communication. It could also make it harder for entrepreneurs to compete with established tech companies, according to critics such as Rice University Engineering School Professor Moshe Vardi, director of the Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology.

In the absence of net neutrality, Vardi said, a company like AT&T could decide to raise the price on internet telephony like Skype. “That means that if Moshe Vardi, a Rice professor, wants to launch a service called Vardype, which would compete with Skype, his small company cannot afford the high price demanded by AT&T,” Vardi continued. “So Vardype has to pass the cost to its customers.” Even if Vardype were much better than Skype, Varid said, the inability to draw enough paying customers would force it out of business.

In addition to expecting return on their investment, the telecoms maintain, net neutrality impedes them from investing in new technologies. Repeal critics counter that net neutrality is not merely about “pipes,” or broadband. “If the customer wants a bigger pipe, the customer should have to pay more for it,” Vardi said. “What happens inside that pipe on the Internet highway: That is the business of the customer.”

As of the summer of 2017, a majority of U.S. American consumers appeared to agree. In a national survey of more than 1,000 Americans conducted by Consumer Reports last July, fifty-seven percent of respondents backed net neutrality, 16 percent opposed the rule, and about a quarter had no opinion. A larger majority – 67 percent – said the telecoms shouldn’t be allowed to modify or edit the content that consumers try to access on the Internet.

Meanwhile, economist Hal Singer, an opponent of the original net neutrality rule, warns that simply repealing and depending on courts to protect consumers and competition may not work as intended. Designed to protect consumers and competition, Singer wrote, the legal system is also expensive and slow. “If the net neutrality concern is a loss to edge innovation,” he said, “a slow-paced antitrust court is not the right venue."

Below, some background on how net neutrality works.

What exactly is net neutrality?

Net Neutrality, a term coined by Columbia University media law professor Tim Wu in 2003, is the principle that Internet service providers (ISPs) must treat all data on the Internet the same, without discriminating or charging differently by user, content, website, platform, application, type of attached equipment, or method of communication.

The regulation was an extension of the longstanding concept of a common carrier, originally used to describe the role of telephone systems.

Under net neutrality, the large Internet providers were prevented from requiring customers to pay to get their content delivered more quickly than their rivals, or for throttling other services and websites by block customer access to sites like YouTube or online newspapers.

FCC chairman Pai’s proposal, passed on Thursday, allowed telecom companies to sell customers a basic internet plan that might include only limited access to Google and email. For Facebook and Twitter, for example, a customer may need to pay for a more expensive plan.

The ISPs argued that the common carrier concept, which originally assigned the companies to the same status as utilities, was an outmoded and overly restrictive concept for a modern technology like the Internet.

A little history

The four largest national wireless carriers haven’t always been subject to rules. That changed in 2015. In 2014, former president Barack Obama recommended that the FCC reclassify broadband Internet service as a telecommunications service as a way to preserve net neutrality.

Back then, the FCC received 3.7 million comments supporting the status of the Internet as a telecommunications service. The outpouring of comments pressured the FCC to uphold net neutrality. (This time around, almost 22 million comments have been filed with the U.S. government on the issue although there have been charges that there have been faked submissions in favor of repeal).

In 2015, the FCC ruled in favor of net neutrality. Broadband access was reclassified as a telecommunications service, and Internet service providers had to obey the requirements of common carrier status.

After the Net Neutrality rule took effect later in 2015, United States Telecom Association, an industry trade group, filed a lawsuit against the FCC challenging the rule. A U.S. appeals court upheld the FCC’s Net Neutrality policies by 2-1 the following year.

In 2017, after President Donald Trump took office, his newly appointed FCC commissioner Ajit Pai announced the agency took issue with a ‘utility-style regulatory approach’ to the telecommunication industry’ and would contest the Net Neutrality rule. The agency voted to end the rule in December of 2017.

Down this superhighway before

The big telecoms have violated net neutrality in the past. In 2007, Comcast was caught secretly throttling, or slowing, uploads from peer-to-peer file sharing (P2P) applications. The company continued blocking these applications such as BitTorrent, until the FCC ordered them to stop. AT&T was caught limiting access to FaceTime, so only users who paid for its new shared data plans could access the application. And in July, 2017, Verizon Wireless was accused of throttling after users noticed that videos played on Netflix and YouTube were slower than usual. Verizon said it was conducting “network testing” and that net neutrality rules permit “reasonable network management practices.”

Taking sides

Heavyweights in technology and business have lined up on both sides of the issue.

Supporting repeal of Net Neutrality were such luminaries as Bob Kahn, inventor of TCP/IP, the fundamental communication protocols at the heart of the Internet; Prize-winning economist Gary Becker, the co-founder of Netscape; Marc Andreessen, co-author of Mosaic web browser; Peter Thiel, co-founder and former CEO of PayPal, and Nicholas Negroponte, an architect and founder of the MIT Media Lab.

Among the industry stars and web pioneers supporting Net Neutrality were Tim Berners-Lee, an Oxford University professor and inventor of the World Wide Web; Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple Inc., and Vinton Cerf, a Web pioneer who is recognized as ‘the father of Internet.’

Now what?

Even after the December 2017 vote, supporters and detractors of Net Neutrality generally agree on one thing: The decision by FCC commissioner Pai is not likely to be the final word. Lawsuits were already underway within the same week to challenge the FCC’s actions, and the political winds could shift again.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Intelligence Community

How do you make heavy-hitting research light enough on its feet to be useful?

How Do You Make Heavy — Hitting Research Light Enough On Its Feet To Be Useful?

RBW: Why did you decide to start publishing concise, online translations of faculty research?

KR: Former Rice Business Dean William Glick, like our current dean, Peter Rodriguez, believed that academic thought leadership must provide the foundation for the education provided at the business school. Personally, I felt that while my faculty colleagues were regularly making major discoveries or adding to the common body of knowledge in business in impressive ways, it was largely a well-kept secret. Obviously, our students experience the benefits of learning from such thought leaders firsthand when they take their courses. But outside of that, our stakeholders — students, alumni, corporate partners, friends, etc. — were largely in the dark about faculty research.

RBW: What do you think is most often misunderstood about business school research?

KR: The idea of what academic research in business entails is itself often misunderstood. Sometimes I joke with people who look surprised when I say I’m doing accounting research, ‘Are you wondering what we can research when debits always equal credits?’ In reality, the type of research academics do is like creating a landscape to be viewed from a satellite. You won’t necessarily see the minute details of the plants — that is, the details a business professional may need to address in the real world. Instead, you’ll get a map or framework that can help you navigate new opportunities and practical problems. I’d view Business Wisdom as a success if it means that anyone can immediately understand the research focus of one of my colleagues — and why it’s relevant for shaping their business practices.

RBW: What's the difference between a Rice Business Wisdom piece and a reference to a journal article in a mainstream media story?

KR: The news media tends to focus on news that can elicit an immediate emotion, response or action. If I tried to follow the advice from every piece of health research I see discussed in media, I would be restocking my kitchen every other day and starting a new exercise regimen. Most times, the type of research we do doesn’t fit the bill for immediate gratification, although there are exceptions. The recent Houston Chronicle article by my colleagues Erik Dane and James Weston, “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” (p. 10), is a case in point. Business Wisdom was created as a vehicle to transmit the timeless discoveries that my colleagues make, but it is well complemented by articles like this one, in which the relevance of the school’s thought leadership becomes readily apparent.

K. Ramesh is the Herbert S. Autrey Professor of Accounting at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

A Luxury You Can Afford

How time and distance change how you feel about your hotel.

Based on research by Ajay Kalra and Wei Zhang

How Time And Distance Change How You Feel About Your Hotel

- Circumstances play a major role in consumer choice and satisfaction.

- Customers who book hotels far in advance are more likely to pick expensive hotels — and to be happy with them.

- Time and emotion color how consumers feel about their hotel accommodations.

An office worker gazes dreamily at their computer, looking for the perfect hotel for their vacation in Venice. For an instant, they hovers on a website offering simple but clean accommodations at a modest price. Then they scroll onward, hitting “submit” on a high-end destination with a spa, trendy restaurant and lavish linens. Why did they choose the sumptuous hotel instead of the economical one? And how will they feel about that choice at the end of their stay?

Researchers used to assume that shoppers balanced quality and price in order to make their choices. But there’s far more to it than that. Research shows that variables that may seem totally circumstantial play a powerful role both in consumer choice and in later satisfaction. If the daydreaming office worker had booked their room from home instead of work, for instance, they would have likely picked the cheaper option. And whether they went upscale or moderate, if they paid three months in advance instead of three weeks, they would have liked their hotel more.

Ajay Kalra, a professor at Rice Business, studied shoppers’ use of online travel sites to discern how they choose and rate hotels, and how circumstantial variables sway their decisions. Contrary to conventional wisdom, he found, outside factors such as distance traveled and the date that a hotel was booked affected both the quality of accommodation travelers chose and even their perception of the hotel after their stay. For instance, travelers heading to distant cities chose better hotels than those staycationing near home. Yet curiously, these long-distance travelers came away less happy with their lodgings than those who stayed nearby.

Time made a difference too. Customers who reserved early chose better hotels and rated them more highly than travelers who booked at the last minute. Even the hour of day mattered: Travelers who booked during the workday chose higher-quality hotels than those who booked during their time off. Yet those who booked from work rated hotels more harshly than those who chose from home.

What could be behind the impact of such seemingly irrelevant details? Working with Wei Zhang of the Ivy College of Business at Iowa State University, Kalra found that standard economic approaches offered little explanation. So the researchers turned instead to psychological theory. What they found suggests that managers should track circumstantial variables as well as more standard metrics in order to predict consumer choices.

The key to the unusual findings, Kalra and Zhang argue, is the power of the past. According to a model called construal-level theory, variables that seem completely random wield power because of the emotional impact of time. As events grow more distant, consumers see them in a more abstract way, sometimes through rose-colored glasses. In contrast, they tend to view recent events in a more detailed and specific way. Thus, variables that at first glance seem random can predict consumer selection and satisfaction with some accuracy.

To get a deeper understanding of these patterns, Kalra and Zhang used the lens of “consumption episodes,” breaking trips down into related purchases such as airfare, hotels and meals. The idea is that most vacation shoppers seek a peak experience, so they buy the highest quality product they can afford across all areas. Traveling far and then staying at a mediocre hotel could undermine the peak experience, so those traveling greater distances seek out higher quality lodging, food and the rest.

Exhaustion, stress, hunger or just a long day at work can affect decision-making. Research into a model called depletion theory shows that judges make a higher percentage of favorable decisions after snack breaks, and that people who are tired are more likely to splash out on pricey consumer items. This may explain, Kalra and Zhang suggest, why vacationers who book hotels from the office crave more luxurious accommodations than those who reserve from the comfort of their couches at home.

Timing and payment method can also affect customer choice. According to the theory of prospective accounting, the pain of paying is dulled when done far in advance, for example by credit card. Consumers who prepay for vacations experience a gulf between payment and consumption, so the vacation feels free. This could account for the high satisfaction rate among travelers who book hotels far in advance.

Teased from data and analyzed through social science, Kalra’s findings offer concrete guidance for sellers and consumers alike. Managers need to accept that some aspects of consumer rating satisfaction are completely out of their control — and they should make sure their superiors know this too. This is particularly important in companies that evaluate employee performance on customer satisfaction metrics.

Consumers, especially travelers, it turns out, have more control over their experience than they might imagine. It may be hard to predict the weather in Europe or the construction schedule outside your hotel room window, but book early enough to forget paying, and click “submit” from the living room with a cat curled nearby, and you just might treat yourself to a free upgrade.

Ajay Kalra is the Herbert S. Autrey Professor of Marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Zhang, W. & Kalra, A. (2014). A joint examination of quality choice and satisfaction: The impact of circumstantial variables. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(4), 448-462. .

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

When Giants Walk The Earth

What happens to individual consumers when corporations boom?

Based on research by Gustavo Grullon, Yelena Larkin and Roni Michaely

What Happens To Individual Consumers When Corporations Boom?

- In the last 15 years, consolidation of public firms and large corporations has concentrated product market share.

- These mergers, which lead to greater market power, yield hefty stock returns.

- While stockholders clearly benefit from this concentration of market share, it’s not clear if the reduced competition helps or hurts U.S. consumers.

Big business is evolving. During the second half of the 20th century, tariff cuts and deregulations drastically changed the industrial landscape of many markets. Between 1950 and 1999, these changes markedly lowered the concentration levels in most industries.

But in a recent paper, Rice Business professor Gustavo Grullon shows that since the beginning of the 21st century, this trend has reversed. The changes he documents are massive: three-quarters of U.S. industries have become more concentrated in the past 15 years, Grullon notes. Large companies are merging at record pace, continuing to strengthen their market share formidably.

Grullon’s research also shows that in the last two decades, the United States lost half of its publicly traded companies. But while there are fewer public firms now than in the early 1970s, their share of the U.S. real gross domestic product has actually grown.

What are the consequences of this trend? First, Grullon found, the firms in more concentrated markets outperform those in less concentrated markets. So an investment strategy that buys firms in industries with higher concentration levels, and shorts firms in industries with lower concentration levels, generates, on average, an abnormal return of about nine percent per year. This suggests that industry concentration probably weakened competition in the U.S., Grullon wrote.

At the same time, Grullon found, private firms did not replace the public firms that disappeared from the market. True, more private firms entered the economy. But their contribution to product market activity overall has actually been small.

These findings, Grullon wrote, suggest that “despite popular beliefs, competition could have been fading over time.” Profit margins have grown, but not necessarily because of greater productivity or efficiency. Instead, they’re the result of higher operating margins.

In other words, mergers deliver investors bigger profits, thanks to a potential increase in market power.

The question should prompt policymakers to look further into the repercussions of megamergers and the reduced competition that attends them, Grullon argued.

As industries consolidate into a few publicly traded companies, there’s no question that companies and stockholders reap the benefits. Individual consumers, however, are another matter, Grullon found. There’s still much to learn about how merger mania affects the people who keep the giants in business.

Gustavo Grullon is Jesse H. Jones Professor of Finance at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

For more information please read: Grullon, G., Larkin, Y., and Michaely, R. (2019). Are U.S. Industries Becoming More Concentrated? Review of Finance, 23(4), 697–743.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Perfect Harmony

Oil supply and demand are hitting the same note.

By William M. Arnold

Oil Supply And Demand Are Hitting The Same Note

This article originally appeared in The Hill and is reprinted here with permission.

News this week of oil prices hovering near $60 a barrel simply reflects the intersection of supply and demand. Demand is gaining strength as the global economy strengthens — supported by oil prices that are about half of their 2014 peak.

OPEC countries, led by Saudi Arabia and other large producers like Russia, have been more decisive and effective in controlling production. This is not to say that every large producer has cut back; however, the net effect has strengthened prices — but not to the point of killing off rising demand.

In the background are five drivers that get less attention: the small and decreasing imbalance between supply and demand, levels of investment, the normal operational decrease in production, the short-cycle nature of production in the U.S. and the inventory of oil.

In a world market of about 93 million barrels of oil and liquid fuels per day, an excess of supply over demand of less than 2 percent was enough to tank oil prices in 2014, driving them all the way down to the high $20s before climbing slowly to today’s prices.

This reflects the commodity nature of oil, the price of which will gravitate to the cost for the producer who supplies the last barrel to balance the market. Higher-cost producers will be driven out over time, although this may not be linear.

In a $110-plus price world, almost any production anywhere in the world was profitable but adversely impacted demand. But much lower prices put high-cost producers at a great disadvantage. That impacts remote areas like the Arctic, lower-quality crudes like those produced in Canada’s oil sands and in Venezuela, regions with poor infrastructure and deepwater production around the world.

Commodity prices are volatile in both directions. An oversupply like we have seen in the last three years drives prices dramatically lower, but a shortfall could take prices back to the former high levels. Is that likely to happen?

Over the last three years, companies have shed staff and slashed billions of dollars from investments to discover and produce oil in the future. That doesn’t have much impact on supply in the short term, but over three to five years, it will crimp production and trend toward higher prices.

Oil fields outside of OPEC on average decline by about 5 percent each year. That takes more than 2 million barrels per day out of global production. Companies are constantly on a treadmill to replace those reserves. Without new investment, that puts upward pressure on prices.

The “shale revolution” upset the traditional view of energy economics, because much of it is short-cycle. Instead of investing for production that won’t come onstream for three to five years, as in the case of deepwater or Arctic sources, production in places like the Permian Basin of West Texas has become more like a manufacturing process that can be turned off or ratcheted up in a matter of weeks, depending on oil prices and the cost of production at a given site.

OPEC has never seen this kind of competition before and is only now coming to grips with it. Adding to the disruption in energy markets has been the unanticipated but dramatic cost reduction of producing oil in the shale play. Former generalizations about the cost of production may be obsolete.

Initially, that was the result of hard bargaining between operators and service companies, but over the last three years, operators have employed new technology and processes to drive down costs more sustainably.

What this means is that absent a surge in demand or a dramatic shortfall in supply, say from a crisis in Venezuela, prices are likely to cap at West Texas costs of production that cover invested capital, probably in the $55-$60 range.

The final driver is inventory of oil. This has been at record levels while production outstripped demand. That has moderated in recent months, but still represents a limit on traders’ expectations of future prices. Stored reserves represent potential new supply that can cap prices.

Bringing all these factors together suggest that while oil prices may be “lower for longer,” an equilibrium has settled in. Demand has grown in response to moderate prices. Whether this will continue is not a foregone conclusion, as OPEC struggles with dissent among its members and there is no shortage of political instability around the world.

Over time, competition from natural gas and renewables cloud oil’s price horizon.

William Arnold was a professor in the practice of energy management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

The Hidden Advantage of Overqualified Workers

Slightly-to-moderately overqualified employees are more likely to reimagine their roles — and become indispensable contributors.

Based on research by Jing Zhou, Bilian Lin (Chinese University of Hong Kong) and Kenneth Law (Chinese University of Hong Kong)

Key findings:

- Past research warned against hiring overqualified workers.

- In fact, slightly-to-moderately overqualified workers are more likely to be valuable and to reimagine their duties in ways that advance their institutions.

- To capture this advantage, employers need to give workers a strong sense of connection with the company, and the flexibility to expand their vision of their jobs.

You’re a rocket scientist. You worked for NASA. You've won a Nobel Prize. Shouldn’t your qualifications give you an edge on a software developer job?

According to typical hiring practice, the answer is no. You might not even get an interview for a job sweeping the floor. That’s because, for years, research has warned that hiring applicants with too much experience or too many skills will saddle you with employees who don’t appreciate their jobs.

Now there’s good news for rocket scientists and others who happen to be overqualified for their work. According to a groundbreaking new study coauthored by Rice Business professor Jing Zhou, workers who are slightly to moderately overqualified are actually more likely to be active and creative contributors to their workplace. As a result, they’re more likely to be assets. The study adds to a new body of research about the advantages of an overqualified workforce.

Zhou’s findings have widespread implications. Worldwide, almost half of the people who work for a living report that they are overqualified for their jobs. That means Zhou’s research, conducted with Bilian Lin and Kenneth Law of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, applies to a vast segment of the labor market.

To reach its conclusions, Zhou’s team launched two separate studies in China. The first looked at six different schools with a total of 327 teachers and 85 supervisors. The second analyzed an electronic equipment factory with 297 technicians. Both studies revealed a strong link between perceived slight and moderate overqualification and the frequency of “task crafting,” that is, expanding the parameters of the work in more innovative and productive ways.

In the school study, teachers who were slightly to moderately overqualified set up new online networks with students and parents. They also rearranged classrooms in ways that made students more engaged and productive. Meanwhile, in the factory, workers took tests to gauge their abilities in complex tasks designing a ship. The ones who were slightly to moderately overqualified built more complex versions that reflected their superior competencies.

The key to both sets of workers’ superiority was their impulse to “job craft.” Every worker leaves a personal imprint: meeting the bare minimum of criteria, pushing to exceed expectations, innovating or imagining new or more useful ways of getting the job done. Expert “job crafters” turn this impulse into an art. Some redraw their task boundaries or change the number of tasks they take on. Others reconfigure their work materials or redefine their jobs altogether. Still others rearrange their work spaces and reimagine their work procedures in ways that can catapult their productivity upward.

For overqualified workers, Zhou’s team found, task crafting is a psychological coping mechanism — a welcome one. Workers want to show their superiors the true level of their skills. Doing so fortifies their self-esteem and intensifies their bonds with the company they work for. Far from being dissatisfied, these overqualified workers are more productive, keen to help their organizations and interested in finding ways to be proud of their work.

So how did the outlook on such workers go from shadowy to brilliant? Past research, it turns out, focused rigidly on the fit between worker experience and a task. It didn’t consider the nuanced human motivations that go into working, nor the full range of creativity or flexibility possible in getting a job done.

Thus, older studies cautioned that overqualified workers are likely to feel deprived and resentful. Zhou’s research shows the opposite: a statistical correlation between worker overqualification and high job performance.

Organizations do need to do their part for this alchemy to work. Above all, Zhou writes, it’s crucial to build a strong bond between worker and institution. This is because workers who identify strongly with their workplace feel more confident that their job-crafting efforts will be well received; those who don’t feel this strong bond often feel mistreated and give up the project of crafting their work.

Similarly, companies also need to grant workers flexibility to expand the scope or improve the process of their jobs. The outcome can be the evolution of the entire business in unexpected and often creative ways.

Not all super-qualified workers will be inspired to re-craft their tasks. When the gulf between skills and task is extreme, Zhou writes, workers are bored and job crafting loses its juice as an incentive. For more moderately overqualified employees, however, their expertise should rocket their CVs to the top of the stack. For seasoned workers, the evidence shows, a job is not just a job. It’s an adventure in finding ways to be excellent.

Lin, B., Law, K. S., & Zhou, J. (2017). “Why is underemployment related to creativity and OCB? A task-crafting explanation of the curvilinear moderated relations.” Academy of Management Journal, 60(1): 156-177. https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/amj.2014.0470.

Mary Gibbs Jones Professor of Management and Psychology – Organizational Behavior

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Letter Of The Law

Research shows that anti-discrimination laws protecting gay, lesbian and bisexual workers’ rights work.

Based on research by Michelle "Mikki" Hebl, Laura Barron, Cody Bren Cox and Abigail R. Corrington

Does Legislating Fairness Work?

- Laws banning discrimination against gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals work.

- The laws reduce discrimination not only by setting consequences for discrimination, but also by reaffirming shared social values.

- Anti-discrimination laws and policies lessen the stigma of homosexuality at work and beyond.

Opponents of laws banning discrimination based on sexual orientation often question whether these laws are effective.

The short answer: they are. Not only do targeted laws reduce employment discrimination against gay, lesbian and bisexual workers, they actually boost acceptance of gay, lesbian and bisexual job applicants.

That’s according to recent findings by Rice Business professor Michelle Hebl and colleagues Laura Barron of the U.S. Air Force, Cody Bren Cox of the Department of Psychology at Texas A&M-San Antonio and Abigail R. Corrington, a psychology professor at Rice.

In their study, the researchers note that politicians have often justified opposition to anti-discrimination laws by questioning whether they really accomplish what proponents say they will.

That argument allows lawmakers a face-saving out: Instead of claiming discrimination towards gays and lesbians does not exist, or that its existence is okay, they can simply question the logic of passing laws that may not do anything.

But these laws do work, Hebl and her colleagues found. In fact, their power is twofold: they work because they show that discrimination is illegal and, just as importantly, because they show that repercussion for it is certain and serious.

In addition, the researchers found, anti-discrimination laws carry symbolic value. They establish a societal norm, alerting the community that mistreating gay, lesbian and bisexual people isn’t accepted.

Regardless of whether the laws are vigorously enforced, the scholars write, their existence educates people about what their conduct should be.

In one study, human resource managers were asked to judge various applicants’ chances of getting a job. In states that lacked anti-discrimination statutes, the managers deemed applicants identified as likely gay or lesbian (because they listed scholarships from gay groups) less hirable than their straight counterparts. In states with anti-discrimination laws, by contrast, the managers showed no difference in how they viewed gay and straight applicants.

Of course, to find out whether these laws work, it is necessary to determine if discrimination against gay, lesbian and bisexual employees exists. Hebl and her team cite several studies that demonstrate the existence of such bias, both subtle and formal. One of those studies found that when job applicants in certain states listed membership in gay or lesbian organizations, they were less likely to be invited for interviews than those who didn’t.

Another study demonstrated that gay men in areas with no sexual orientation anti-discrimination laws generally earn less than their straight counterparts.

Other research shows that gay and lesbian employees who work in areas with legal protections are more likely to be open about their sexuality than those in areas with no legal protections. These workers are also more likely to report having gay coworkers and supervisors and to work for organizations with gay-friendly policies.

While the research by Hebl and her colleagues reveals that anti-discrimination laws work, it also reveals that they do so only when the public is well aware of them. Thus, the success of these laws may hinge on how effective public information campaigns and media coverage are. Success also hinges on whether these laws are enforced.

Both awareness and enforcement of these policies are a sound investment, the researchers note. That’s because gay, lesbian and bisexual employees who feel welcome in a workplace tend to perform better. In fact, Hebl and her team argue, businesses in states and cities without anti-discrimination laws should establish their own such policies. Doing so does more than discourage employees from discriminating against gay, lesbian and bisexual coworkers, it also counteracts the notion that homosexuality is abnormal, instead presenting it as just another sexual orientation.

An added benefit: because of its focus on effectiveness, the American workplace is a powerful driver of cultural norms. Companies that prioritize human capital — and punish discrimination — will have a greater range of job applicants, more motivated staff and more creative work environments. They also stand a good chance that the community they serve will follow their lead.

Michelle "Mikki" Hebl is a Martha and Henry Malcolm Lovett Chair of Psychology at Rice University and a Professor of Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business.

To learn more, please see: Hebl, M., Barron, L., Cox, C. B., & Corrington, A. R. (2016). The efficacy of sexual orientation anti-discrimination legislation. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 35(7/8), 449-466.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Battle Cry

Why is the word “embattled” popping up in headlines everywhere?

By Jennifer (Jennie) Latson

How Casual Use Of Militaristic Hyperbole Gets Everyone Up In Arms

On Monday, White House budget director Mick Mulvaney entered the “embattled” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, as it was described in a Wall Street Journal headline, armed only with a supply of donuts.

Somehow, Mulvaney made it out of the metaphorical war zone alive. But he’s far from the only one to find himself the subject of the bellicose buzzword in recent news stories. These days, the word “embattled” punctuates headlines like so many bugle blasts. It has lanced elected officials, business leaders and companies, not to mention entire industries and even regions.

Few people have been more embattled over the past year than Uber founder Travis Kalanick. A Google search for “embattled CEO” produces a wall of posts — almost all about the former head of the scandal-mired ride-hailing company. In June, Slate commented on Kalanick’s near-constant state of embattlement:

People love to describe him as “embattled.” There have been plenty of folks throughout history who were far more embattled than he (the Biblical Abraham, Napoleon, victims of sexual harassment, to name a few). But still, if you look at the past week, you will see that it was quite an embattled one for him.

On June 13, Kalanick announced he would be taking a break from the company. Would this make him any less embattled? Fat chance. “Uber's embattled CEO, Travis Kalanick, is taking an indefinite leave of absence,” read Vox’s headline.

Kalanick isn’t the only one to buckle under the weight of the word, though.

In March, “embattled bankers” embraced President Trump’s call for financial deregulation (and found themselves “suddenly feeling emboldened,” according to the Washington Post). But Trump himself has been “embattled” almost since the day he took office. So has nearly everyone who works for him — or did, until they became too embattled. The casualties of embattlement include former press secretary Sean Spicer, chief strategist Stephen Bannon, chief of staff Reince Priebus, national security adviser Michael Flynn and Attorney General Jeff Sessions. (Short-lived communications director Anthony Scaramucci seems not to have occupied office long enough to earn the moniker.)

Still, embattlement implies, well, a battle. So what are all these embattled people up against? The question is particularly murky for Trump, the Washington Post suggests in “Donald Trump: An embattled president … without a battle.” When Trump’s approval rating slipped to 35 percent in March, the Post noted that he was “the first president on record to go that low without it owing to one of three things: war, Watergate or economic strife.”

If the battle lines are hard to draw, then why does “embattled” suddenly seem to be hurling itself into every other headline? For one thing, drawing on militaristic hyperbole is a way to inject drama into otherwise mundane stories. A “troubled” or “struggling” leader doesn’t carry quite the same weight, says the editor Roy Peter Clark, who writes about language for the Poynter Institute, an organization that teaches journalistic ethics and practices.

Last year, Clark observed that news writers were overusing another militaristic cliché: “firestorm.” In an essay, he called it an example of “unmitigated hyperbole as a way of heating up coverage. It’s the journalist or commentator as carnival barker: ‘Step right up, ladies and gentlemen, and watch the amazing firestorm of controversy…’”

Today he sees fewer “firestorms” but more “embattled” people — and the fact that both words derive from war matters, he said. The word itself is medieval, derived from Middle English and first recorded in the 14th century, when hordes of Europeans were, quite literally, embattled.

“If you think of yourself as being embattled, you have to imagine that there’s an army of people out to get you, and that you are a combatant on one side or another,” Clark explained. “That kind of metaphorical language is a lens through which we see the world. The problem is that when we think of the world that democracy creates, we talk about a civil society, and that’s a completely different set of metaphors. What does it mean to be civil to another person? It means to treat them NOT as if they’re your enemy, but as if you had the ability to work out your differences.”

Using the language of hyperbolic violence fuels division and intolerance, said Rice English Professor Terrence Doody.

“What I’ve been noticing is that people now do not grant any tolerance to opposing views. You don’t say, ‘I can understand how you see things, but I don’t view it that way,’” he said. “It’s ‘You’re evil and I hate you.’ If you use that level of hyperbole, there’s no chance of reconciliation.”

This is a new development in American rhetoric, Doody believes. Even at other divisive moments in our nation’s history, the language was never so extreme. Consider the Civil Rights movement, he says.

“If you listen to Martin Luther King’s speeches, they have a wonderful churchly rhetoric. They’re not violent, they’re very traditional, very calm,” he said.

To create a more civil society, we need people who use language publicly — people like journalists, business leaders and politicians — to start a backlash against violent metaphors, Doody said.

“We’d have to call it something other than a backlash, though,” he added. “That’s a violent term, too.”

But what about the targets of terms like “embattled”? Once labeled as such, can they ever become un-embattled again? After all, the word tends to describe politicians and executives just before they move on to descriptors like “ousted,” “fired,” and “former.”

That doesn’t stop embattled leaders from aiming for other adjectives, of course. Take United Airlines CEO Oscar Munoz, whose reputation came under siege after a United passenger was dragged from his seat in April. Munoz, who won a PR award just weeks before fumbling his apology for the scandal, has tried to battle his way back into the public’s good graces.

His best hope for recovery was to increase customer satisfaction by improving service quality — in part by making employees happier, Vikas Mittal, a marketing professor at Rice Business, said at the time.

“To truly turn United around, Munoz, the board, and all United management and workers need to re-school themselves on the basics of customer satisfaction,” Mittal wrote. It seems Munoz has taken that advice to heart — and, at least to some degree, succeeded.

After Hurricane Harvey hit Houston, Munoz made headlines with a more civility-minded purpose: his promise of a generous donation in matching storm relief funds. Nowhere was he described as “embattled.” A Fox News story used no adjectives at all, in fact, creating a blank canvas that must have looked, to the once-embattled eye, like a white flag.

Jennifer Latson is an editor at Rice Business Wisdom and the author of The Boy Who Loved Too Much, a nonfiction book about a rare disorder called Williams syndrome.

Never Miss A Story