Apply now for Rice Business Plan Competition

The world’s richest and largest startup business competition is now open for applications from students around the globe. Graduate students with startup ventures are encouraged to apply for the 19th annual Rice Business Plan Competition (RBPC) April 4-6 at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business. Winners will be rewarded with prizes expected to exceed $1.5 million.

The world’s richest and largest startup business competition is now open for applications from students around the globe.

Graduate students with startup ventures are encouraged to apply for the 19th annual Rice Business Plan Competition (RBPC) April 4-6 at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business. Winners will be rewarded with prizes expected to exceed $1.5 million.

The deadline for applications is 5 p.m. CST Feb. 10. Students will need to answer a short questionnaire, submit an executive summary and an optional one-minute video pitch through the competition’s website, http://rbpc.rice.edu.

The annual competition, which attracts students from the world’s top universities, is expected to draw more than 500 teams in 2019. All applications will be reviewed by a committee comprising select members of the entrepreneurship and investment community. The field of finalists will be narrowed to 42 teams, and a cohort of 275 judges will decide which company represents the best investment opportunity.

New for this year: The RBPC has a custom-designed application, judging and scoring system. Developed and managed by Poetic, a Houston-based business technology solutions firm, the new platform will allow the RBPC to be more flexible and innovative than ever before.

The winner of the grand prize will ring the closing bell at the Nasdaq MarketSite in New York.

More than 200 former competitors have successfully launched their ventures and are still in business today, including 25 startups that have been acquired. Past competitors have raised over $1.9 billion in capital and created more than 3,000 new jobs.

“The true measure of success for the Rice Business Plan Competition is the number of teams that launch, raise funding and go on to succeed in their business,” said Brad Burke, managing director of the Rice Alliance for Technology and Entrepreneurship at Rice University, which hosts the event. “The competition has served as the launch pad for a great number of successful entrepreneurial ventures, and the success rate far exceeds the national average.”

The startup teams will compete in four categories: life sciences/medical devices/digital health; digital/information technology/mobile; energy/clean technology/sustainability; and other innovations. investment opportunity.

Top prizes in 2019 are expected to be similar to last year, including the $300,000 Investment Grand Prize from The GOOSE Society of Texas; the OWL Investment Prizes, which totaled $300,000 in 2018; the $125,000 Houston Angel Network (HAN) Investment Prize; and the $50,000 NASA Space Exploration Innovation Awards.

Cisco is again offering the largest cash prize at the competition. The $100,000 Cisco Global Problem Solver prize aims to recognize entrepreneurs who promote and accelerate the adoption of breakthrough technologies, products and services that capture the value of technological innovation to society. Special consideration will be given to businesses that also benefit the environment.

The second-place investment prize has increased to $125,000 in 2019. Finger Interests, Anderson Family Fund and Greg Novak of Novak Druce have contributed to the prize.

A new prize this year is the $50,000 Pediatric Device Prize. The RBPC is partnering with the Southwest National Pediatric Device Consortium at Texas Children’s Hospital/Baylor College of Medicine to offer this award to support the advancement and commercialization of novel pediatric medical devices. Eligible devices must be FDA-regulated with a pediatric indication (0-21 years of age).

Station Houston offered a $50,000 investment prize and two Engine of Innovation prizes offering last year’s top winners an opportunity to join Station Houston.

A goal of the RBPC competition is to encourage more women to create venture-fundable, technology-based startups, and nCourage Entrepreneurs Investment Group, a group of successful women angel investors, will provide an investment prize to the top startup with female founders. Last year, the group offered two prizes that totaled $100,000.

Sandi Heysinger and Dick Williams have supported a Women’s Health and Wellness prize since 2015, and in 2018 they awarded $65,000 in prizes for a plan or plans that best further the cause of specialized diagnosis, treatments or other innovations that let women lead longer, healthier and more satisfying lives.

The Texas Medical Center Accelerator, TMCx, offered two investment prizes totaling $50,000, plus a guaranteed spot in their accelerator, while the Texas Business Hall of Fame provided a $25,000 cash prize to the top finishing team from Texas. Pearland Economic Development Corporation offered a $20,000 cash prize.

For more information on the 2019 Rice Business Plan Competition and application information, visit http://rbpc.rice.edu.

You May Also Like

Get To The Point

How did we get so hooked on exclamation points?

By Jennifer (Jennie) Latson

How Did We Get So Hooked On Exclamation Points?

If you really want to demonstrate your dislike for someone, end a sentence with a period.

“Thanks so much.” “That’s great.” “Happy birthday.” As a line in an email, a text, or a Facebook comment, any of these will effectively convey your contempt and devastate the recipient. By now, we all know that if you actually mean it, you’ll use an exclamation point — or several.

In one recent study, undergraduates at Binghamton University-State University of New York reported that text messages ending in a period struck them as abrupt and insincere. As the Wall Street Journal reported, “It’s especially bad in the workplace, where an exclamation point can suggest anything from actual excitement or gratitude, to general friendliness, to reassurance that 2 p.m. works for a meeting, to… ‘I’m not mad about the other day. I swear, it’s fine!’ ”

How did the exclamation point come to dominate our correspondence? It started with a cultural shift in the way we communicate, linguists say. As written communication — via email, text, instant messaging and social media — came to replace many of our in-person conversations, we lost a vital element of expression. Words, after all, are only part of communication: tone is equally crucial, and notoriously difficult to convey in writing. In person, you can say “thank you” sarcastically with a sneer, or genuinely with a smile. In writing, your options are more limited. That’s where the exclamation point comes in.

“The single exclamation mark is being used not as an intensity marker, but as a sincerity marker,” linguist Gretchen McCulloch told The Atlantic’s Julie Beck. “If I end an email with ‘Thanks!,’ I’m not shouting or being particularly enthusiastic; I’m just trying to convey that I’m sincerely thankful, and I’m saying it with a bit of a social smile.”

In fact, one exclamation point is barely enough, even in the buttoned-up world of business communication. “Digital communication is undergoing exclamation-point inflation,” Beck said. “When single exclamation points adorn every sentence in a business email, it takes two to convey true enthusiasm. Or three. Or four. Or more.”

Where does it end? The problem with runaway inflation — exclamatory or otherwise — is that it doesn’t, says James Weston, a finance professor at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business.

In a (mostly) tongue-in-cheek email, he writes: “Inflation in any form is dangerous! Once inflation starts, it gets very hard to stop!! Each time inflation rises, it makes the past inflation look tame!!!! It always feels like a good decision in the moment!!!!!!!! But the long-run societal consequences of inflationary policy are devastating!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Hyperinflation is, more often than not, a precursor to war!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

Not everyone is worried. Geoff Nunberg — a linguist at UC Berkeley’s School of Information and the author of “Ascent of the A-Word,” along with several other books about language — doubts that exclamation point inflation will bring on World War III.

“I’ll be alarmed if I see multiple exclamation points starting to bristle in the pages of the New Yorker or the New York Times,” he says, “but I find it hard to get indignant when they pop up in texts, tweets or informal email exchanges, which are really just the written versions of communications that used to take place orally.”

Still, the English majors among us cling to the doctrine that an exclamation point should be reserved for extreme circumstances (for example: “Shark!”). Multiple exclamation points, we insist, are grammatical overkill, permissible only in the rarest of cases (“Oedipus, she’s your mother!!!”). But since our arguments typically end in periods, they haven’t garnered much attention.

Exclamation points are, after all, the Swiss Army knife of punctuation marks. They can be used to express a variety of emotions: excitement, glee, disbelief, outrage or anger. The writer doesn’t even have to commit to a usage; it’s up to the reader to interpret as she sees fit.

“Exclamation points are emphatic, but offer no inclination, affect, or meaning other than the superlative. They are loud but neutral,” explains Judith Roof, the William Shakespeare Professor of English at Rice.

That makes them a popular choice for the linguistically lazy. “Ultimately and sadly, I think the use of the exclamation point is also linked to the last 15 years’ gradual loss of vocabulary, expressive capacity, and overall linguistic mastery,” Roof says.

Constance Elise Porter, a marketing professor at Rice Business, agrees that the exclamation point epidemic is partly an indicator of our deteriorating writing skills. Although we may communicate in writing more than ever before, the kind of writing we’re doing is brisker, briefer, and less thoughtful, she argues. When we exchange texts and tweets, short emails and quick Facebook updates, we’re sacrificing both style and substance for another priority: speed.

“In this world of fast and acceptably incomplete written communication, the exclamation point seems to be the communicator's way of capturing everything that just takes too long to actually articulate in the most exciting way,” she says.

It’s also a mark of our desire to seem interesting — to rise above the noise on social media, Porter says. Except, of course, that now everyone’s using them, so no one stands out. And that means that true exclamations — of the “Shark!” variety — may be obscured.

“Unfortunately, I think that what will happen is that we will begin to ignore the true meaning of the exclamation point — like the boy who cried wolf — and a truly meaningful, alarming, scary or otherwise escalated-emotion-laden event will have difficulty breaking through the clutter,” Porter cautions.

But English majors needn’t worry. “If this happens, then the greatest communicators will find a way for their voices to be heard,” she says. “The lazy communicators will remain lost in the sea of exclamation points.”

Jennifer Latson is a staff writer and editor at Rice Business and the author of The Boy Who Loved Too Much.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Your Mood May Skew Your Moral Compass

Employees who feel sad are more likely to carefully analyze extreme, unethical behavior than those who feel happy or disgusted.

Based on research by Vikas Mittal, Karen Page Winterich (Penn State) and Andrea C. Morales (Arizona State)

Key findings:

- Emotions affect the way we understand ethical situations.

- To parse how the way we feel affects the way we think, Vikas Mittal and colleagues studied more than 700 participants, inducing states of mind easily found in any workplace.

- Employees who feel sad are more likely to carefully analyze extreme, unethical behavior than those who feel happy or disgusted.

Somebody left crumpled paper towels in the office restroom. A cat meme made you laugh out loud. Your coworker recently lost his elderly parent. Nearly every day of our working lives, we face situations that unleash a range of emotions.

Do these emotions affect our understanding of ethics? In a recent study, Rice Business professor Vikas Mittal joined Karen Page Winterich of Pennsylvania State University and Andrea C. Morales of Arizona State University to see if sadness, disgust or happiness impact the way we understand and react to ethics-based decisions.

The answer: yes, absolutely.

To parse how people respond to unethical behavior when they are sad, happy or disgusted, the researchers launched three separate studies involving more than 700 participants. They induced states of mind easily found in any workplace. Images of a dirty restroom triggered disgust; news of a positive work evaluation sparked joy.

When workers felt disgusted or happy, the researchers discovered, their brains engaged in heuristic processing – that is, using mental shortcuts to process information. When they felt sad, however, their minds churned in more complex ways: Their judgments about unethical behavior were slower and more deliberative than when they were either happy or disgusted. The processing was similarly slow when they were in a neutral state of mind.

Neither type of mental processing is inherently good or bad. But it does affect how workers see ethical decisions. Compared to those whose state of mind is sad or merely neutral, happy or disgusted people tend to see minor moral infractions as less important. Different emotional states, in other words, affect our judgment of an ethical infraction’s magnitude.

To draw causal conclusions about the magnitude of these judgments, the researchers induced sadness, disgust or happiness in participants by asking them to write an autobiographical passage recalling a time when they felt one of those emotions. This primed the subjects with that specific emotional state, after which the researchers presented them with a variety of different unethical behaviors.

Some of the hypothetical infractions were financial. In one experiment, for example, the subjects read scenarios describing behaviors such as tax fraud, insurance fraud and outright theft. And some of the scenarios were nonfinancial, but horrifying: For example, subjects were told to imagine situations involving cannibalism.

When a subject feels disgust, the researchers reasoned, it triggers a distancing reaction, leading her to withdraw both physically and psychologically. After all, people seem to naturally pull back from any disgusting situation. Because of this distancing effect, the subjects brains processed the unethical scenarios heuristically, using mental shortcuts.

Interestingly, subjects who felt cheerful showed a response similar to that of people who were repulsed. That’s because happy people rely more on mental shortcuts and don’t bother systematically processing their judgments. Just like disgusted people, they tend to heuristically process whatever tasks they engage in, Mittal and his colleagues write.

These shortcuts essentially meant that the subjects who felt disgust or happiness relied almost entirely on the gravity of an infraction itself to make moral judgments on unethical behaviors.

The workplace implications are significant. Employees or managers who feel sad, Mittal writes, are more likely to pull their weight and carefully analyze unethical behavior, however extreme or minor. Conversely, workers who are either disgusted or happy rely more on simply the magnitude of the ethical infraction when making judgments.

Most employees aren’t interested in embezzling a million dollars from the company coffers. But they might be tempted to fudge an expense report or pocket office supplies after hours.

So if a coworker seems fixated on the icky washroom floor, or has simply fallen deliriously in love, it may worth a gentle reminder that if they see something unethical happening, they should say something. Even if it requires a second look.

Winterich, K. P., Morales, A. C., & Mittal, V. (2015). Disgusted or happy, it is not so bad: Emotional mini-max in unethical judgments. Journal of Business Ethics, 130.2: 343-360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2228-2.

J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Super-sorter Marie Kondo joins the reality brigade

The home purge TV show is now as rigorously structured as the hero's journey or a Petrarchan sonnet. In it we see the act of decluttering as a quest, and the tidied home as a proxy for our reborn selves. It's a form wonderfully suited to the animistic methods of Marie Kondo, the Japanese tidiying guru who taught the world to kiss its socks goodbye with a novel organising principle: if your belongings don't spark joy, thank them for their service and show them the door.

Expert: Here's one way the Catholic Church can regain some of its credibility

In 2005, a grand jury issued a report finding leaders concealed sexual abuse by priests there for four decades. Rice Business Professor, Anastasiya Zavayalova, has been examining how parishioners reacted to the archdiocese releasing names of the priests involved.

Exclamation points are everywhere?!

Where does it end? The problem with runaway inflation — exclamatory or otherwise — is that it doesn't, says James Weston, a finance professor at Rice University's Jones Graduate School of Business.

Looking to cut clutter from your life? Here's where to start

Clutter: why we have it, what it does to us and how to climb out from under its heavy burden.

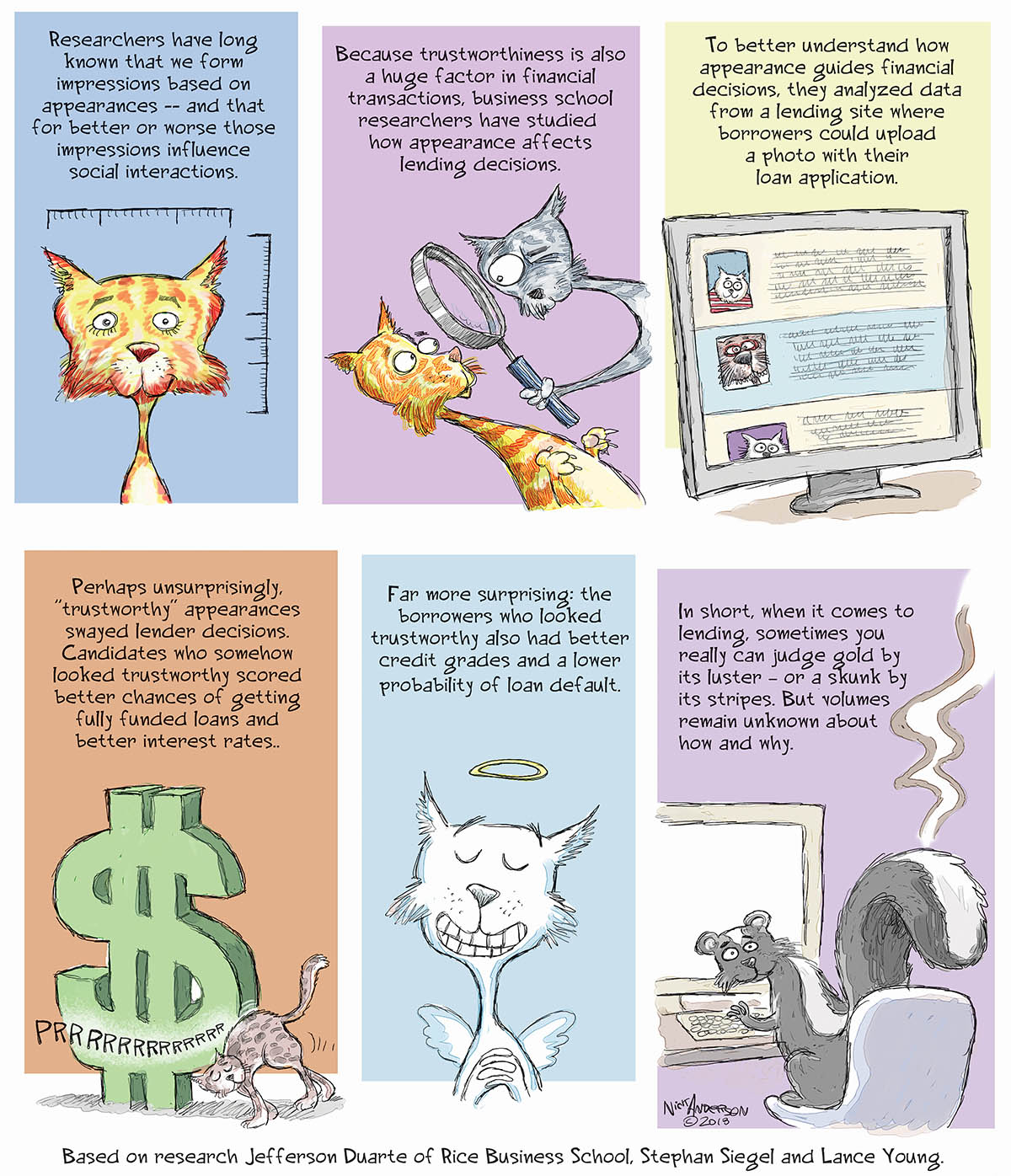

Lie Detector

Can a snapshot reveal your chances of a loan?

Illustrated by Nick Anderson. Based on research by Jefferson Duarte.

Can A Snapshot Reveal Your Chances Of A Loan?

To learn more, please see: Duarte, J., Siegel, S., & Young, L. (2012). Trust and credit: The role of appearance in peer-to-peer lending. Review of Financial Studies, 25, 2455-2484.

To learn more, please read: Trust Me On This

Jefferson Duarte is an associate professor of finance the Gerald D. Hines Professor of Real Estate Finance at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Nick Anderson is a Pultizer Prize-winning editorial cartoonist.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

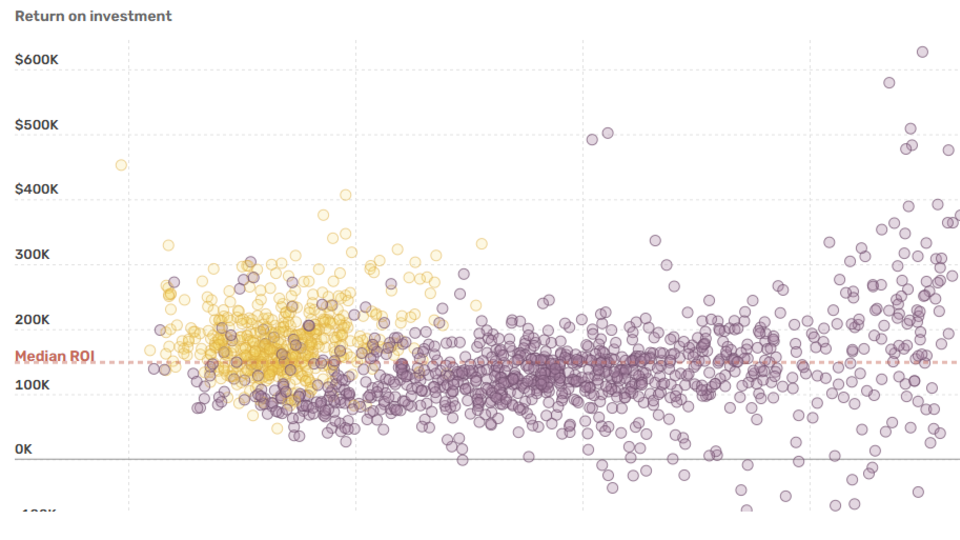

Extra Credit

Want reliable credit ratings? Improve reporting.

Based on research by Brian Akins

Want Reliable Credit Ratings? Improve Reporting.

- When Credit Rating Agencies have access to better financial reporting, there’s greater agreement among agencies and less credit risk uncertainty.

- After the 1997 implementation of Statement of Financial Accounting Standards, firms that were most affected by the standards had less credit risk uncertainty.

- While higher quality financial reporting lowers risk uncertainty for all credit reporting agencies, it’s especially important for agencies that rely heavily on publicly available reports.

Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) help make the economy go ‘round. That’s why investors rely so heavily on CRAs such as Moody’s Investor Service (Moody’s) and Standard and Poor’s (S&P) to let them know how likely their “bet” is to pay them back in a timely fashion — or ever.

So imagine that you’re thinking of investing in a company with a strong credit rating from a top CRA. As you conduct your due diligence, you discover that yet another top CRA has assigned the very same firm a significantly lower credit rating, indicating that it’s more likely to default on its loans.

Not surprisingly, this disagreement between the CRAs introduces a greater uncertainty of risk, which could influence your investment decision. You might decide you need a higher yield, or request any number of other measures to protect yourself from the perceived risk.

Fortunately for would-be investors, Rice Business professor Brian Akins set out to find out what can be done to increase the harmony between CRA ratings. In particular, he wanted to know if improving the financial reporting that CRAs use would lower the risk uncertainty that ensues when they disagree.

To find out, Akins studied data from three major CRAs: Moody’s and S&P — both of which have access to not just public reports but also corporations’ private information — and Egan-Jones Rating Company (EJR), which relies mainly on public reports.

Akins began by trying to see if reporting quality affected disagreement between Moody’s and S&P, since they have access to similar data. As an indicator of reporting quality, Akins used a measure called “debt contracting value of accounting” (DCV), which shows how well a firm’s earnings information predicts a possible rating change. He calculated the DCV for 1,959 bonds representing 875 firms that were rated by both S&P and Moody’s between 1985 and 2008.

Next, Akins looked at the default risk that S&P and Moody’s assigned to each of these 1,959 bonds. He found that on average, the higher the DCV — that is, the higher the reporting quality — the more likely the agencies were to agree in their ratings. In other words, better reporting quality was indeed linked to less risk uncertainty.

But what about firms such as EJR, which doesn’t have the luxury of accessing a corporation’s privately available information?

Akins found that for EJR, better reporting quality was even more important. That’s because nearly all of the data the firm uses come from the “publicly available” bucket, so the better the quality of this data, the more aligned its ratings will be with other agencies.

Akins wanted to be sure that reporting quality, and nothing else, was indeed the key variable at play, so he analyzed the level of disagreement among credit ratings before and after a mandatory change was made to accounting standards in 1997. This change, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) 131, is recognized as having improved reporting quality.

What Akins found is that after SFAS 131 was put into effect, the firms most impacted by the standards had far less disagreement on their credit ratings than similar firms less affected by SFAS 131. Consistent with Akins’ earlier findings, better reporting quality meant more consistent ratings.

In short, when CRAs analyze firms that have higher quality reporting to determine their ratings, they’re more likely to agree on those ratings. This, in turn, means less risk uncertainty for investors, who can be more decisive. Because when it comes to investing money, no one likes surprises.

Brian Akins is an Assistant Professor of Accounting at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Akins, B. (2018). Financial reporting quality and uncertainty about credit risk among the credit ratings agencies. The Accounting Review, 93(4), 1-22.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Marie Kondo, super-sorter, gets her own reality show

Her third and latest book, ‘Joy at Work: The Career-Changing Magic of Tidying Up’, written with Scott Sonenshein, a professor of management at Rice University School of Business, out this coming spring, was bought at a competitive auction for seven figures by Little, Brown, said her US agent, Neil Gudovitz.