Alumni Club

What Happens If The Fund Manager Played Lacrosse With The CEO?

Based on research by Alexander Butler and Umit G. Gurun

What Happens If The Fund Manager Played Lacrosse With The CEO?

- Mutual fund managers with social or educational links to a particular CEO tend to invest in that CEO’s company.

- The portfolios of managers with social or educational links to a CEO perform better than the portfolios of managers without such social connections.

- CEOs with social or school links to mutual fund managers get paid more than those without such connections.

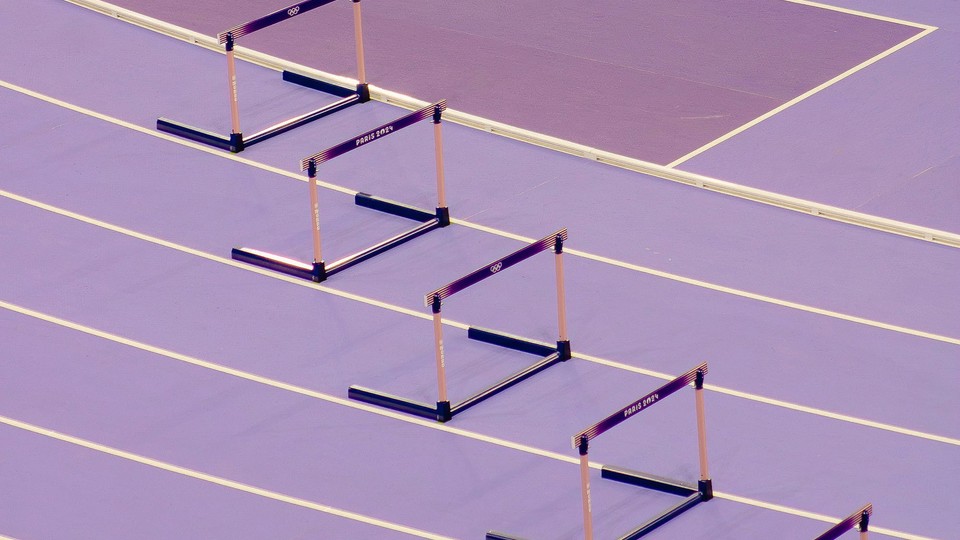

Friends help each other out, right? Imagine young men or women racing down a New England playing field, effortlessly passing a lacrosse ball on their way to the goal. Now imagine some of those old friends as CEOs of large firms, and others as managers of mutual funds. Do they still have each other’s backs?

That was the question Rice Business Professor Alexander W. Butler explored in a recent paper. What he found makes perfect sense given human nature, and raises serious questions about the dynamics of the financial market.

Yes, Butler and his coauthor, Umit G. Gurun of the University of Texas at Dallas, found, CEOs of publicly traded corporations and mutual fund managers from the same schools do appear to help each other out. It may be conscious or unconscious: They do what friends do the world over. But the effect on the market can be profound.

To trace the role of social connections in the world of corporate and finance, Butler and Gurun studied how mutual fund managers vote when shareholders proposed limiting executive pay. They cross-referenced these data with information about the educational background of the firms’ executives and of the mutual fund managers who took part in the votes.

When voting fund managers and an executive went to the same schools, Butler found, those halcyon days at A&M or Wharton clearly corresponded to fewer votes to limit executive pay.

Now, this may reflect all kinds of things. Shared school ties could mean fund managers have more relevant information about a firm’s CEO and his or her value. The shared culture and vocabulary of a school environment might ease information flow between a CEO and managers. But there is also another possibility: Perhaps the value a mutual fund manager places on a CEO’s firm has nothing to do with the company’s actual value. The manager may simply support him because he’s a school friend.

CEOs weren’t the only ones to benefit from old-school ties. Well-connected investors prospered too. When a fund manager shared a school background with a given CEO, Butler found, the fund outperformed funds whose managers weren’t part of the network. For investors as well as CEOs, in other words, school ties with decision makers at mutual funds raised the chances of a winning outcome.

So a shared school or social background leads to well-paid CEOs, successful fund managers and happy investors. What’s not to celebrate?

Plenty, it turns out.

The better trading outcomes of well-connected mutual fund managers have implications far beyond one happy set of shareholders. The Securities and Exchange Commission protects a level playing field because it’s in the public interest for the U.S. financial markets to be liquid.

Consumers buy and sell stocks more easily when they are confident that a product’s price is reasonably close to its actual value. When one party seems to know more about a stock — perhaps through friendship with the CEO — other investors may lose confidence that they can assess the value of stocks as accurately. When too many consumers distrust the market, liquidity drops. Fewer people buy and sell.

Think how much easier it is to buy a used car with public resources such as Carfax, or pre-owned car certifications. In the past, a buyer had to wonder what a car seller knew but wasn’t saying — or else try to buy a car from someone she already knew and trusted.

Almost everyone has a friend. Almost everyone has experienced the memories, common lingo and wordless sense of goodwill that come from sharing a common history. Butler and Gurun’s study of corporate and financial markets, however, shows how these natural instincts can disadvantage players outside the alumni circle. Shareholders may have less power to limit CEO pay. And consumers may end up less confident about the value of stocks, shaking trust in the financial markets overall. Surely, that’s not what friends are for.

Alexander W. Butler is a professor of finance at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Butler, A. W. & Gurun, U. G. (2012). Educational networks, mutual fund voting patterns and CEO compensation. The Review of Financial Studies, 25(8), 2533-2562.

Never Miss A Story