Saving Face

Rice Business professor Anastasiya Zavyalova shares three tips for CEOs facing a PR crisis.

Video of Anastasiya Zavyalova

Video: Three Steps For CEOs Of Embattled Companies

Rice Business professor Anastasiya Zavyalova shares three tips for CEOs facing a PR crisis:

Anastasiya Zavyalova is an associate professor of strategic management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Making Beautiful Music

There’s more to customer loyalty than meets the ear.

Based on research by Vikas Mittal, Markus Blut, Carly M. Frennea and David L. Mothersbaugh

There’s More To Customer Loyalty Than Meets The Ear

- Costs, administrative headaches and loss of established relationships play a part in customer decisions to change a service or product provider.

- Strategic companies need to take these switching costs into account, along with customer satisfaction, as they devise strategies for keeping customers.

- The psychological price of suspending relationships with a company’s employees or brands is more significant to customers than other switching costs.

“You gotta know the territory,” sings a salesman in Meredith Willson’s classic Broadway show The Music Man. You gotta know your customers, too, according to a recent study, because customer loyalty often depends less on what a customer thinks of a product — and more on what she thinks of the people behind it.

Any business knows it needs to get customers and to keep them. What makes some customers want an encore transaction and others leave after the first act, though, is less than obvious. Understanding those choices, however, is critical if companies hope to strategically manage their customers–a firm’s most valuable asset.

Vikas Mittal, a professor at Rice Business, teamed with Markus Blut, now of Aston Business School in Birmingham, England, David Mothersbaugh of the Culverhouse College of Commerce at the University of Alabama, and Carly M. Frennea, a doctoral student at Rice Business, to look at customers’ decisions to come back or move on.

The researchers focused on switching costs — the one-time costs associated with changing a service or product provider — and how these costs compare with customer satisfaction as influences on decisions to repeat business.

The study looked at three kinds of switching costs: procedural, financial and relational. Procedural costs are the time and effort required to identify and contract with a new provider. Financial costs are actual monetary expenses, such as fees for breaking contracts or giving up loyalty rewards like frequent-flier miles. And, finally, relational costs are the emotional or psychological tolls of cutting relationships with familiar suppliers or brands.

Vikas and his coauthors conducted a meta-analysis, that is, a statistical analysis of data from a range of published studies. They looked at results of 178 existing studies of decisions made by 133,000 customers.

Because methodology, quality and error vary among studies, meta-analysis is complex work. Putting results together accurately can be like plucking a common melody from hundreds of bands of varying talent playing different songs at the same time. Searching scientific databases and journals for studies, the team applied rigorous statistical analysis to put the material in harmony.

In one 2003 study, long distance telephone and credit card customers clearly weighed switching costs when contemplating repeat purchases. But the report was foggy about the link between switching costs and customer satisfaction. Left unknown: Could high switching costs discourage an unhappy customer from making a change?

A 2015 study offered more insight. Consumer satisfaction, the research showed, diminished in importance in the presence of high relational costs for a supplier. Customers who liked a company and its employees were more forgiving about perceived glitches in satisfaction. Interestingly, the link between procedural and financial costs and customer satisfaction was weaker.

For managers deciding their marketing priorities, the guidance is clear. Client switching costs, especially those involving relationships, may be as important to repeat business as the quality of the product itself. So here’s the coda: Truly knowing your customer is key to business, whether you’re selling one widget or 76 trombones.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing and Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Blut, M., Frennea, C., Mittal, V., & Mothersbaugh, D. (2015). How procedural, financial and relational switching costs affect customer satisfaction, repurchase intentions and repurchase behavior: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 32(2), 226-229.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

In Advertising We Trust

Elected officials make policy. What gets them elected?

Based on research by Antonio Merlo (former professor at Rice University) and Arianna Degan

Elected Officials Make Policy. What Gets Them Elected?

- Increasing the information people have about candidates’ positions raises the likelihood that registered voters will vote.

- Strategies that link candidates with information about what they stand for, accurate or not, sway elections.

- Fake news, while it doesn’t improve real understanding of candidates, nevertheless spurs voter participation. So accurate information for voters is a crucial matter of public policy.

The president. Congressional representatives. Judges, mayors, school district officials. High and low, elected officials make the policies that make our society. And because those policies directly shape profitability, it’s in the best interest of business to understand exactly how leaders get into office.

In 2011, Antonio Merlo, former Dean of the School of Social Sciences, teamed with co-author Arianna Degan of the Université du Québec à Montréal to analyze the 2000 U.S. presidential and congressional elections. The presidential election, of course, was the historically close race that George W. Bush won after a Supreme Court-ordered recount in Florida. In addition to the presidential race, Merlo and Degan looked at dozens of lesser-known races to learn about the issues that sent voters to the polls–or kept them home.

Picture a family Thanksgiving with five individuals who differ in age, race, gender, education, religion and income, as well as party identification. With analysis, this potentially contentious meal reveals a banquet of observable characteristics that social scientists can link with measurable information about knowledge of candidates, a sense of civic duty, ideological preferences and even personal sense of regret, if making a mistake when voting.

To draw general conclusions from this type of individual profile, Merlo and his co-author first collected voter data from two large sources: the American National Election Studies and the Poole & Rosenthal NOMINATE Scores. They ran these numbers through a specially created model that quantified relationships between observed factors such as individual characteristics and voting patterns, which were found in the data, and unobserved factors such as information, civic duty and ideological leaning.

The model did more than correctly predict electoral turnout in both large races and small — it accurately predicted if voters participated in multiple elections or just one. Increasing the information citizens have about candidates’ positions, the scholars concluded, raises the likelihood that registered voters will, in fact, vote, even when they’re facing a long list of elections and candidates.

Knowing a candidate’s position, the scholars added, infuses voters with confidence. A fully informed voter seems to worry less about accidentally pulling the lever (or spinning the dial) for someone with whom he or she disagrees.

Once they found the prediction model worked, Merlo and Degan went a step further, experimenting with policies that might increase electoral participation. They discovered that policies that effectively inform voters of candidates’ stances correlated with the voters showing up on election day, voting a split ticket rather than only for one party and simply skipping ballot items when unsure about whom to vote for.

The more a voter knew, in other words, the less anxious she was about using that knowledge and expressing her opinion through the ballot box.

Policies meant to boost a sense of civic duty also raised voter participation. In congressional elections, the scholars found, a voter’s familiarity with a candidate’s positions, at least in certain cases, gave the candidate a measurable advantage.

There’s good reason candidates pour all that money into TV ads, Merlo and his co-author confirmed. Indisputably, strategies that link candidates with information about what they stand for (accurate or not) sway elections. The growing blizzard of fake news, while it doesn’t improve real understanding of candidates, nevertheless spurs voter participation. Accurate voter information, in other words, is not only a campaign issue, or a business issue. It’s a matter of public policy.

Six years after the scholars published their findings, in a new landscape of bots, cyber-meddling and homegrown fake news, understanding voter behavior is more urgent than ever. Elected officials make policy that affects the conduct of business. But voter confidence, knowledge and, at times, misinformation are what shape the elections that shape U.S. society.

Antonio Merlo is the forner Dean of the School of Social Sciences at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Merlo, A. & Degan, A. (2011). A structural model of turnout and voting in multiple elections. Journal of European Economic Association, 9(2), 209 – 245.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Failure To Communicate

The surprising way faulty English affects trading.

Based on research by Patricia Naranjo, Francois Brochet and Gwen Yu

The Surprising Way Faulty English Affects Trading

- First-rate command of English language is essential for overseas firms that deal with capital markets in conference calls.

- Analysts rely on clear English skills to assess risks and opportunities.

- Conference calls from countries where the language is linguistically furthest from English are more opaque, which in turn mutes the trading response.

Nineteenth century philologist L.L. Zamenhof dreamed of ending global misunderstanding. His solution: a brand new language, Esperanto. Zamenhof’s plan never took off, of course. But global business could probably use it.

In a groundbreaking new study, Patricia Naranjo, a professor at Rice Business, joined François Brochet of Boston University and Gwen Yu of Harvard University to look at the way language problems in conference calls can affect the stock price of a given firm.

Language barriers, the team demonstrated, are linked to lower information content for potential investors, which leads to a subdued market reaction during the time the conference call is taking place.

The implications for profit making are clear. But the research also has an ethical component. In 1998, the Securities and Exchange Commission established guidelines for English usage called the Plain English Initiative. All investment products come with risks, the SEC reasoned, and investors can’t be fully informed unless the data are stated plainly.

Scholars, too, have for years called for better analysis of international corporate disclosures. But most studies on the topic examine earnings releases. Those that specifically look at conference calls consider calls within the United States. Naranjo and her colleagues instead tackled the complex give-and-take of calls that included international players.

To measure the quality of English in conference calls, and its effects on the markets, Naranjo’s team analyzed a sample of 11,305 conference call transcripts from non-U.S. firms between 2001 and 2010. Sifting through the transcripts, they kept only those from the hours when the markets were open. Then they tracked the speakers’ grammatical errors and the market activity while the call took place. The goal was to sound out market reaction to the conference calls’ language.

The reaction was loud and clear. The more an executive’s national language differed from English — say, if she was Italian or Japanese — the less linguistic clarity there was during a conference call.

Unsurprisingly, managers from countries such as Japan and Italy were more prone to use expressions that didn’t quite make sense in English. They also made more errors in grammar. Managers from the United Kingdom, Australia or India, meanwhile, used clearer English.

But why do bad similes and clumsy verb tenses affect trading? It’s because a lot more happens in a conference call than the dry reading of figures. These conversations are a manager’s chance to explain the meaning of the financials she is presenting. Analysts, especially those who live outside of a firm’s home country, rely heavily on these calls for clear information. When the language in these talks gets muddy, confidence in the information presented plunges. Trading drops as a result.

The opposite happens when an executive sounds like she attended Cambridge or Rice. She’s far less likely to make language mistakes, of course. The market also reacts more strongly to the information presented. To put it quantitatively: During a conference call question and answer period, a one-standard-deviation rise in language clarity led to a 3.76 percent rise in abnormal trading.

Naranjo’s research speaks volumes to overseas firms that rely on capital markets. As long as English rules as the linguistic coin of the realm, it pays to train executives to speak fluent English, or to factor existing English language ability as a coveted job skill. L.L. Zamenhof was a student of language, not finance. But his 19th century analysis of individual behavior accurately described the human hive-mind that is the market. When language fails, Zamenhof knew, misunderstanding and error soon follow. And in the end, numbers will tell the tale.

Patricia Naranjo is a former assistant professor of accounting at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Brochet, F., Naranjo, P., & Yu, G. (2016). The capital market consequences of language barriers in the conference calls of non-U.S. firms. The Accounting Review, 91(4), 1023–1049.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

No Place Like Home

A consumer's sense of local identity will drive them to pay more for products that reinforce that identity.

Based on research by Vikas Mittal, Huachao Gao and Yinlong Zhang

When A Consumer's Sense Of Local Identity Is Triggered, They Will Pay More For Products That Reinforce That Identity

- Marketers have long known that consumers who feel a strong sense of local identity will pay more to buy products that are locally made.

- “Local identity,” in academic terms, means valuing local traditions and causes.

- Striking new research shows that when a consumer’s sense of local identity is triggered, he or she will pay more for products that reinforce that identity — even if the products are manufactured elsewhere.

More powerful than fact, more persuasive than numbers, more compelling even than protecting one’s wallet: the instinct to identify with a group. This desire is one of the most potent drivers of human behavior, and in a recent study, Rice Business professor Vikas Mittal revealed just how powerful that drive can be. For everyday grocery shoppers, he found, the sense of local identity overpowers even the desire to save money.

“Buy American” has been a political mantra for generations, with advocates insisting that U.S. shoppers are willing to pay more for sweatshirts, strawberries and car parts if they’re made in the USA. Times, though, are tough for many Americans. Have their priorities changed?

Not at all, Mittal and his colleagues found. The reality around what we think of as a fair price is actually quite nuanced, and it’s heavily influenced by who we feel we are.

In a series of 14 studies that could redefine how major corporations market to local buyers, Mittal joined Huachao Gao of the University of Victoria and Yinlong Zhang of the University of Texas to analyze the impact of local identity on consumer choice.

While two of the studies took place in China, with the other 12 taking place in the United States, the outcomes were the same. Consumers were willing to pay more for products that reinforced their sense of belonging to a local community.

To reach these findings, the team deployed a battery of surveys, experiments and randomized field data, each designed to tease out if consumers would pay more for foreign products from stores that labeled themselves “Buy Local” advocates.

In theoretical terms, the team was testing the consumer sacrifice mindset, a state in which shoppers are willing to make a sacrifice such as paying more. This mindset, the researchers found, can eclipse the ordinary wish to get the best price — if, that is, marketers can trigger the sense of local identity.

When local identity launches a sacrifice mindset, Mittal and his colleagues found, consumers worry less about the prices of all products, not just the local ones.

In one of the most significant studies, the research team asked 186 shoppers at a large grocery store in China to fill out a survey indicating how many eggs they would buy at the current price, and how many they’d be willing to buy if the price jumped by 5, 10 or 15 per cent.

The researchers then measured each shopper’s self-perception as a local citizen — someone who prioritizes local values and customs — or a global citizen — someone who prioritizes global values and customs more.

In a second study, the researchers handed shoppers two brochures announcing an impending price hike on eggs, rice and milk. One set of consumers received a brochure that urged them to value local customs, and was sprinkled with local news items. The second group’s brochure encouraged them to see themselves as part of a global community, and was filled with snippets from international news.

The brochures made a big difference. Shoppers whose local identity had been stoked bought more eggs than shoppers prompted to think of themselves as part of a bigger world.

The conclusion? Consumers with a strong local identity are less sensitive to price than those who feel a more global outlook. The implications are broad. If a company can inspire local identity in consumers, they’ll be less sensitive to price increases on all products, not just the local ones. Walmart has already demonstrated this principle in action.

In a recent campaign, the company told consumers it would be spending more locally and hiring more local workers. Amazingly, this was enough to boost revenue 14.5 percent, even though prices went up an average of 12 percent, and no additional products were produced locally.

For companies worried about consumer price sensitivity, in other words, there’s little need to be concerned about local positioning or local production to get buy-in. In fact, it may not be necessary to manufacture locally at all. Sparking a stronger sense of local identity might be all that’s required.

Meanwhile, for “Buy Local” activists who work on causes such as helping local farms, Mittal’s research shows that it’s not enough just to sing the praises of local products. Instead, they too need to invest in sparking consumers’ local identities.

As for consumers, Mittal’s findings may or may not inspire soul-searching. Even the savviest shoppers are not fully conscious of why they are willing to pay certain prices. And it’s worth knowing that feelings of local fervor don’t always translate into support for local producers. When it comes to psychic survival, it turns out, the most powerful weapon isn’t economic. It’s the belief that we’re the people we want to be.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Management in Marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Gao, H., Zhang, Y., & Mittal, V. (2017). How does local-global identity affect price sensitivity? Journal of Marketing, 81(3), 62-79.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Flight School

How United Airlines can change course.

By Vikas Mittal

How United Airlines Can Change Course, According To The Latest Research

"As board members, we only meet infrequently and are not engaged with the front line," confessed United Airlines CEO Oscar Munoz last year during the annual meeting in June. But this spring, when footage of passenger Dr. David Dao being dragged off a United plane swept the internet, it became clear the airline’s leadership needed to engage far better in situations with unhappy passengers. What, exactly, should United Airlines do? Recent research can help school the airline on how to improve.

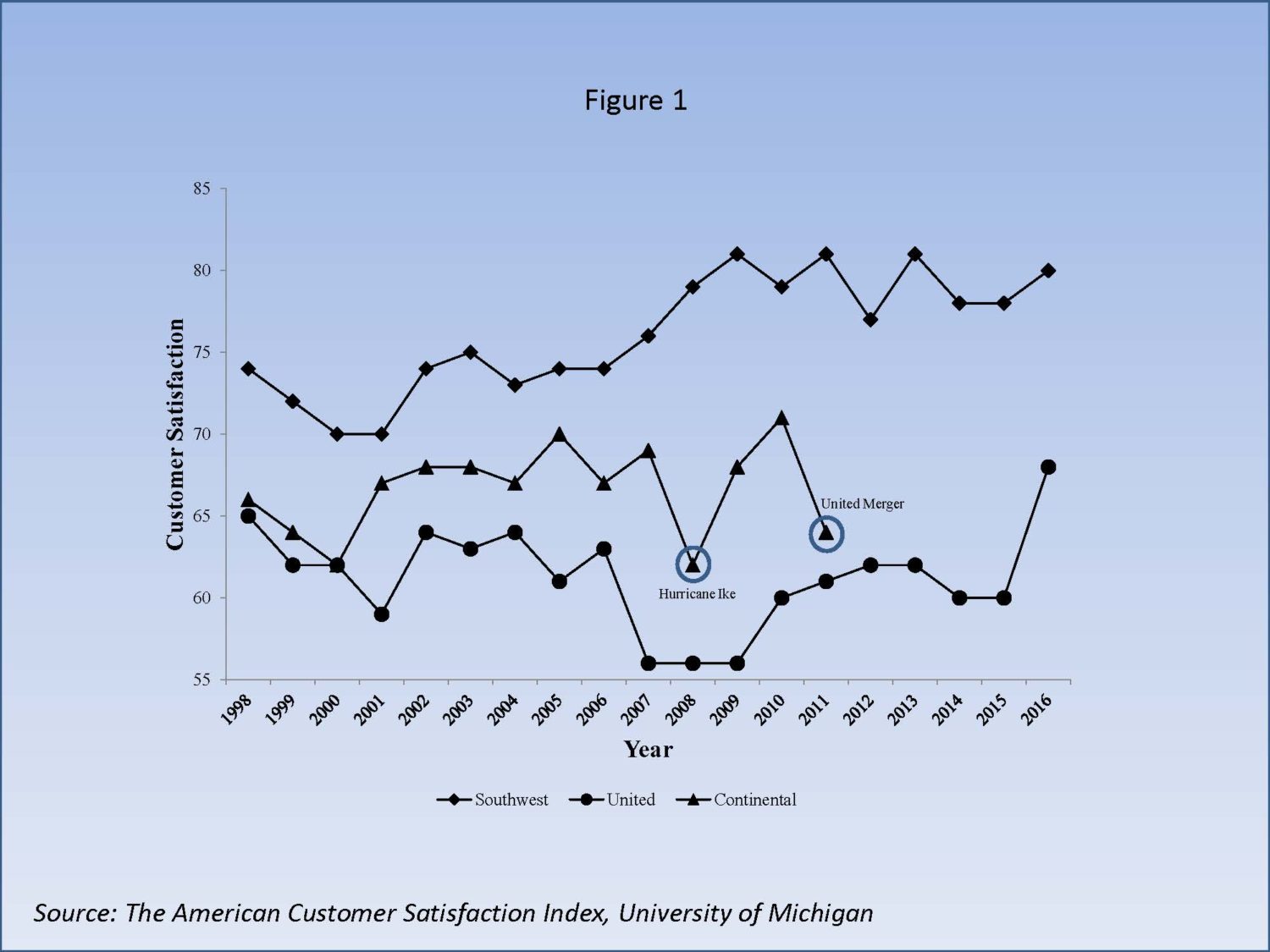

Focus on customer satisfaction: The main source of cash flow for any company is a loyal customer base. Figure 1 below shows customer satisfaction rates for United passengers compared to "best in class," Southwest. The data come from the American Customer Satisfaction Index which provides a uniform and unbiased measure of customer satisfaction. Scores can range from 0-100, with 100 representing the highest level of customer satisfaction.

Since its 2010 merger with Continental Airlines, United's overall satisfaction rate has hovered in the 55-65 range, with Southwest topping 80. Between 2015 and 2016, however, United shows a sharp jump in satisfaction. Whether this reflects a fluke or a trend remains to be seen.

Extensive research links customer satisfaction scores to a firm's financial performance in the long run. To raise customer satisfaction, United should focus on the key factor of improving service quality.

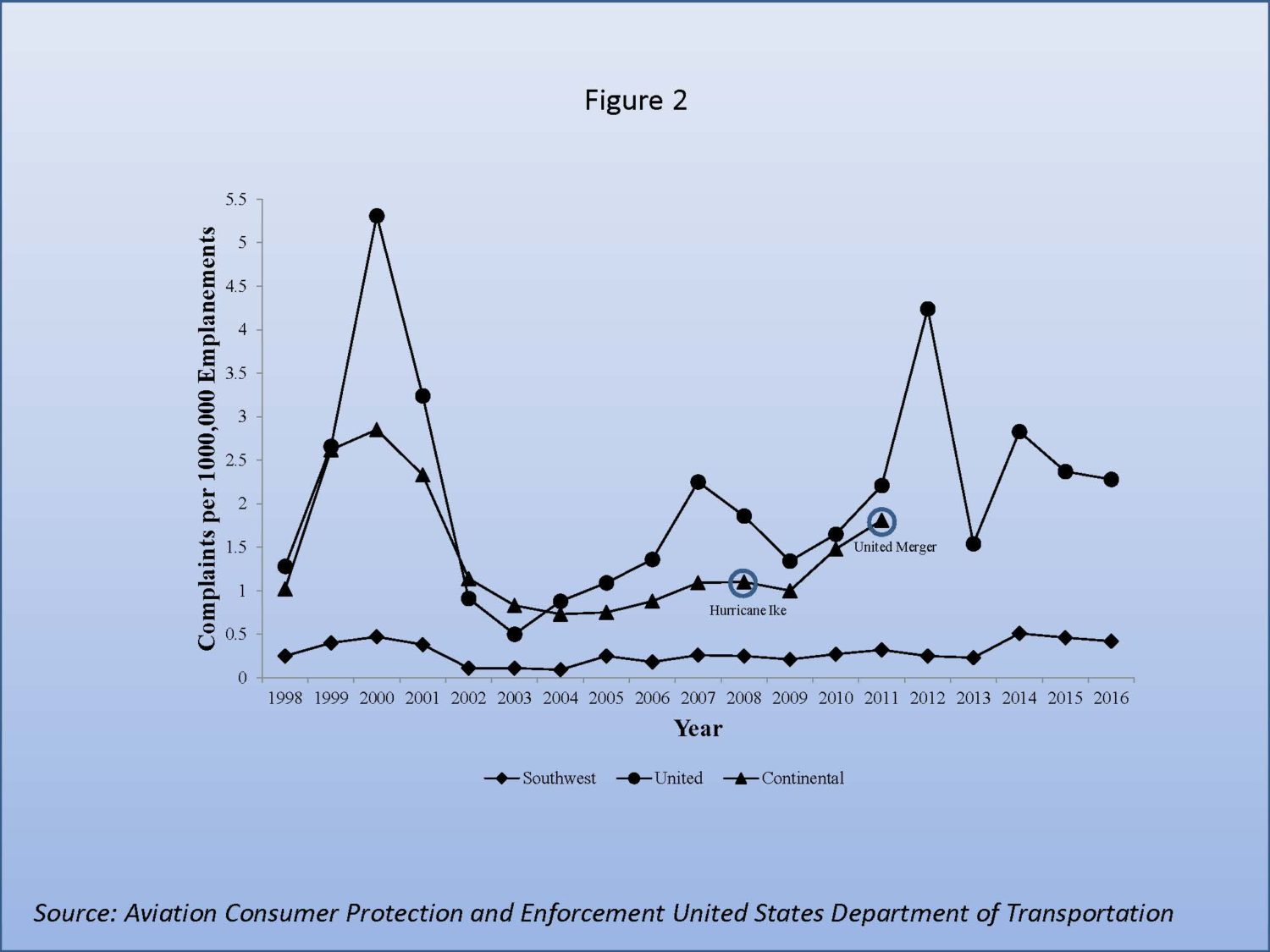

Improve service quality: Customers who experience high levels of service quality complain less. Figure 2 gives a comparative view of complaints on a standardized basis. Southwest has consistently fewer than one complaint per flight, while United scores twice as high on this metric. Scoring high on a complaint metric is not good.

United shows wide gaps in service quality. They may spring from any number of factors: missed flights, lost luggage, inconsistent service, or other flaws. What specific issues are driving lower service quality and customer satisfaction at United? Mr. Munoz and his team need to listen to customers to find out.

To improve satisfaction, listen to customers. Despite exhortations that "Customers are number one!" or "Customer first!" the truth is that many companies put customers last. Caught in a morass of automation, optimization, efficiency-enhancement, revenue management, branding, and advertising, companies forget the simple things that matter for customers. The only way to go back to basics is to listen to the customer’s voice. A structured customer feedback program encompassing qualitative research and quantitative customer research can give United crucial guidance. The information can help the company develop and implement a customer-based strategy for the whole company.

United should be asking: What is the root cause of customer complaints? What attributes and strategic areas drive satisfaction? Which levers should be pulled to improve customer satisfaction, customer retention and customer recommendations?

Invest in employees: Research shows employee satisfaction can indirectly affect the bottom lane by improving customer satisfaction. A recent study by Rice Business professors Vikas Mittal, Christopher Groening and Anthea Zhang showed that CEOs who satisfy both customers and employees can improve the long-term value of their companies by 11%.

For an average S&P company with a market cap of $10 billion, this translates into $1.1 billion in added value. As a point of comparison, the market cap for United in early May was roughly $20 billion. In other words: investing in workers so they can satisfy your customers would be worth about $2 billion.

To meet all these objectives, Munoz and his team have to engage intensely with their company’s two most important sets of stakeholders: customers and employees. Peripheral tinkering with processes and policies are unlikely to help in the long-term. To truly turn United around, Munoz, the board, and all United management and workers need to re-school themselves on the basics of customer satisfaction.

Vikas Mittal is the J. Hugh Liedtke Professor of Marketing and Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Perfect Match

What does it take to make the right hire?

Based on research by Frederick Oswald and Leaetta M. Hough

What Does It Take To Make The Right Hire?

- Measures of technical competence (aptitude tests, high school grades and job knowledge tests) can successfully predict technical performance at work.

- Measures of personal competence (conscientiousness, extraversion) play a bigger role in predicting teamwork, helping behaviors and other types of non-technical performance at work.

- A manager choosing employees to send overseas should consider personal competence — not just technical competence.

Hiring the right person is one of the knottiest tasks managers face. Hiring is rarely simple, and the welter of selection techniques that employment-testing companies sell just makes it more daunting.

How does an employer know which employment tests work? And what’s most important to making a hire: ability or job knowledge, high school or college grades or personality traits such as conscientiousness?

Fred Oswald, a Rice psychology professor, has tackled these questions in his research on personnel selection systems that make use of scores on employment tests. His findings support how well-established tests of cognitive ability or technical competence are some of the best predictors of a job applicant’s future technical performance at work.

Oswald notes that there are cases where these measures can be less accurate when predicting performance on tasks that happen to be simple for all employees (either because they are very easy tasks, or because everyone at work is highly skilled at the task). But more often than not, ability tests successfully predict the technical aspects of employees’ job performance, for most employees and across most jobs.

That said, ability tests, like any test, can be misapplied. For example, if an ability test taps language ability at a twelfth-grade level, but the job only requires language at an eighth-grade level, then well-qualified applicants could get screened out.

Turning to the personality domain, measures of conscientiousness robustly predict the technical aspects of job performance. Higher scores on conscientiousness tests tend to predict higher levels of work performance. Lower scores predict poorer work performance. Even better, this prediction is relatively independent of the prediction that cognitive ability test scores provide. In other words, both cognitive ability and conscientiousness matter when selecting employees.

There’s a caveat, though. If you define conscientiousness as attention to detail and commitment to tasks — even with a catchy label like “grit” or “moxie” — then conscientiousness is required in almost all workers across the board. On the other hand, if you define conscientiousness as conformity and social appropriateness, this trait can often hinder achievement.

Employment tests take time and money. So how extensively should job applicants be tested? Recruitment before hiring is essential. So is training after an applicant is hired, Oswald says. Nevertheless, to tap the full range of available talent, minimize training needs and lower the number of terminations, he proposes that managers consider testing applicants for the types of technical competence and personal competence needed for a job.

In sales, for example, a new hire ought to be reasonably extroverted with customers, agreeable as a team member and open to new experiences as products and organizations change. Scoring 800 on a math SAT certainly won’t hurt. And what about high school or college grades? Go ahead and be impressed by an applicant’s report card, Oswald advises. Getting A’s really does reflect cognitive ability and the kind of conscientiousness that’s needed at work.

Resumes and report cards, though, won’t be enough. True, the track record on a sales applicant’s resume may predict future performance in a new sales job. Yet a highly talented young applicant might lack experience to list on a resume. And an experienced applicant might exaggerate past successes and minimize failures. Employment testing, as an alternative or supplement to resumes, can make hiring more reliable and fair.

What about managers who want to judge interpersonal skills and teamwork with an interview? They should ask all applicants the same, structured questions about job-relevant situations they’ve faced that required interpersonal skills, Oswald recommends. This works better than assuming an applicant has those skills simply because she sailed smoothly through an interview.

The farther a worker strays from home, the more important interpersonal skills seem to get. U.S. hiring managers who work for multinational companies often agonize about which workers to send overseas. The stakes are high, the required cultural and technical skills can be unclear and success is often perplexingly elusive. According to multinational companies, failure rates among expatriate workers are somewhere between 15 and 40 percent.

They may be using the wrong hiring approach, Oswald suggests. It may seem logical at first to hire overseas workers for their technical abilities alone. After all, they have a specific task to do. Why do they need to establish cultural bonds or even a common language with coworkers who simply work for the same company?

Yet personal qualities seem to matter even more with overseas hires. Despite the relative neglect of these qualities in making expatriate assignments, Oswald and other organizational researchers have found that people skills, adaptability and family situation all play central roles in supporting employee success in a foreign workplace. Sure, you can call HQ or log on to get many technical solutions. But if you ever need technical or psychological support from your coworkers, it’s going to help if they want to be around you (or even better, want to invite you to dinner).

So what’s the best way to use these techniques? Use a mix of methods, Oswald says. Make sure to measure technical competence, learning ability and interpersonal skills with tests such as those mentioned. Just confirm that the tests are reliable, valid and fair. Understanding a job applicant’s talents and past conduct in the road test of life can mean as much as the bullet points on his CV. Employee testing can be a powerful part of this approach.

In a few years, we’ll all work alongside robots. They’ll never sleep. Their resumes may eclipse those of any human. But for now, managers still need to assess the complex work units known as human beings. Good science can help, in the form of accurate tools for detecting technical excellence, people skills – and maybe even moxie.

Frederick L. Oswald is a professor in the Department of Psychology at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Hough, L. M., & Oswald, F. L. (2000). Personnel selection: Looking towards the future, remembering the past. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 631–664.

Also please see: Oswald, F. L. (2008). Global personality norms: Multicultural, multinational and managerial. International Journal of Testing, 8(4), 400-408.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Noteworthy

Chris Staffel ’17 traded a career in music for business.

On Chris Staffel, EMBA '17

Chris Staffel ’17 traded a career in music for business.

A native of San Antonio, Chris Staffel grew up thinking she wanted to be a professional singer. After mastering regional theater and a classical tour throughout Russia and Eastern Europe she got tired of living out of a suitcase and put down roots in New York City. The daily grind of auditions drove her to producing. “I realized I enjoyed the business part of it, equally, if not more than acting.”

While she was producing The Dutchman she met two businessmen who were starting a midstream company. “What’s midstream?” She retells it now, laughing. As it turns out, acting and producing isn’t far off from starting and running a company. “You have to raise the capital, hire actors, market the show, and of course... perform.”

But, she adds, “If you would have told me years ago that I’d be building companies for natural gas pipeline infrastructure, I would have never believed you. I went to a music conservatory in Chicago for my undergraduate degree, followed by an M.F.A. in musical theater and then moved to New York to pursue musical theater. I’ve now started three companies in the midstream energy space.”

Even before moving to Houston, she sat in on some classes at Rice and was sold on earning an MBA. “It’s been excellent. I’ve learned so much... The network is incredible.”

Since the sale of PennTex in November, she is curious about the next global opportunities on the horizon in energy and plans to travel to various emerging markets after graduation. “I want to see where the next possibilities are.”

Her most immediate “next possibility” is singing the national anthem at Investiture, the business school’s hooding ceremony for MBAs on the eve of her graduation.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Inside the Box

How a Rice Business professor found a life-saving technology.

Based on research by Douglas A. Schuler, Jean Boubour, Katherine Jensen, Hannah Richter, Josiah Yarbourgh and Z. Maria Oden

How A Rice Business Professor Found A Life-Saving Technology Inspired By A Trip To Sierra Leone

- In low-resource settings, poorly cleaned and unsterile medical instruments play a role in harmful outcomes for patients.

- Recent research at Rice shows that it’s possible to overcome these instrument sterilization problems, even in low-resource areas.

- Rice scholars developed a full-suite sterile processing unit, with its own power and water sources, inside a shipping container.

In 2013, Rice Business professor Douglas Schuler visited Sierra Leone and came home determined to do battle. The country was slowly recovering from a long and brutal civil war, and though the conflict had ended a decade earlier, health threats lurked everywhere.

Simple toothaches were ominous. Childbearing was risky. Infections were often a death sentence. Returning home, Schuler vowed to attack a core problem in Sierra Leone’s health: unclean medical instruments.

Health facilities, Schuler found, struggled with sterilizing their tools for surgery. Teaming with Rice bioengineering professors, undergraduate students and alumni, Schuler saw an opportunity to reduce infections, shorten hospital stays and prevent deaths by crafting a plan for sterilizing surgical tools at a low cost. The solution demanded rethinking not just equipment management, but infrastructure, facility layout and protocols.

Most hospitals in developed countries have the hardware and funds to uphold sterilization standards. But facilities in a developing country such as Sierra Leone can’t rely on their infrastructure for basics like clean water, electricity or even a secure spot for a sterilizing unit. Schuler and his colleagues resolved to find a bridge for those infrastructure gaps.

The first question: where to put the bulky sterilization equipment? Schuler’s revelation: a shipping container. Dividing a container into separate areas, Schuler’s team creates separate spaces for decontamination, preparation, sterilization and drying and storage. The decontamination area uses filtered water pumped from water tanks, plus three sinks to clean the surgical implements. The preparation area includes a steel table, and the sterilization area holds a non-electric, gravity-powered steam sterilizer. Solar panels source electricity for the hot plate and cellphones.

It may be unorthodox, but, the team found, it works. Running surgical instruments through the sterilizer 61 times to test the design and method, Schuler’s team found that the system thoroughly decontaminated and sterilized every time. After crunching the numbers for a statistical analysis, the team concluded with 95 percent confidence that the probability of failure is less than 5 percent. And the system is simple enough that health workers in the field can be trained to use it accurately.

Having shown the potential of this holistic, low-cost sterilization system, Schuler’s team wants to popularize it into other hospitals, clinics and post-disaster settings. The units could also serve patients needing dental, maternal and neonatal care.

Containers also offer possibilities beyond sterilization, Schuler says. A vast transportation network is designed to move shipping containers throughout the world. The units are versatile enough to house diagnostic labs and patient rooms, and their access to electricity makes them possible sites for telemedicine in areas where there are no doctors.

Cost poses a real challenge: The souped-up containers are too pricey for widespread use in poor areas. But the containers offer real benefits to patients and hospitals, and Schuler is currently working on models for potential funders. Already, at least on a technical level, Schuler and his team have shown that sterilization containers can place modern medicine in reach of millions in areas with few resources.

Maybe one day fewer health challenges will lurk beyond ordinary people’s control. Business, philanthropy and bioengineering will surely play a role in this. So will empathy and personal relationships with the communities facing these challenges day to day. The good news is that ingenuity knows no boundaries. And it can travel far if packaged in the right box.

Douglas Schuler is associate professor of business and public policy at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University

To learn more, please see: Boubour, J., Jenson, K., Richter, H., Yarbrough, J., Oden, Z. M., & Schuler, D. A. (2016). A shipping container-based sterile processing unit for low-resources settings. PLoS ONE 11(3).

Never Miss A Story

Keep Exploring

Happy Place

Research on worker well-being is usually more about the company than the worker.

Based on research by Erik Dane and Jennifer M. George

Research On Worker Well-being Is Usually More About The Company Than The Worker

- Researchers have paid relatively little attention to the effect of pay and job security on worker happiness.

- Articles on the subject tend to be written from the viewpoint of management.

- Scholars who really care about employee well-being should look at the role of economics in workplace satisfaction.

Gyms, yoga, juice bars — there are a lot of ways twenty-first century businesses compete to amuse and refresh their employees. And a cottage industry of scholarly research has arisen to advise them on how best to do so.

Despite the abundant literature on worker happiness, however, scholars often overlook how employee pay and job security fit into the equation, write Emeritus Professor Jennifer M. George and former Professor Erik Dane, at the business school. If scholars truly care about employee well-being, George and Dane argue, they need to look at the role of economics.

In particular, the scholars take issue with Aharon Tziner, Erich C. Fein and Assa Birati’s article “Tempering hard times: Integrating well-being metrics into utility analysis” in the December 2014 issue of Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice.

By ignoring the impact of economic issues, the Rice professors argue, Tziner and colleagues neglect a core component of workplace satisfaction. Since the 1970s, economic inequality in the United States has vaulted upwards as workers have struggled with periods of high unemployment. Layoffs are no longer used as last-ditch efforts to save troubled companies, but rather as short-term tools for boosting profits.

Economic markers tell the story bluntly. Census Bureau statistics released in fall 2016 showed the U.S. poverty rate to be 13.5 percent, meaning 43.1 million Americans lived in poverty (defined as a family of four with an income below $24,257). Many workers now face long-term unemployment or job instability. Although in March 2017 the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the unemployment rate being at a near four-decade low of 5.4 percent, many observers argue that these figures only reflect people who have looked for work in the last four weeks, and omits hundreds of thousands of “discouraged workers” who have given up looking for work entirely.

Metrics of employee well-being, George and Dane write, need to take such factors into account. Unless employees make enough money to meet their needs, the researchers argue, finding meaning in work becomes problematic. Yet such metrics rarely surface in research or in strategic decision-making. Though authors of previous articles have cited shareholders as critical stakeholders, they have rarely acknowledged that workers are stakeholders too.

Even those scholars who see employees as central to an organization tend to focus on the role of worker well-being on business. Consider the research on “dysfunctional turnover,” when workers quit of their own volition or lose their jobs during downsizing. Researchers typically address the fallout: flagging performance among workers left behind, the costs of recruiting new workers, lost customers, overtime pay — and disturbances in the normal functioning of the whole organization. What they don’t mention is the devastation that layoffs wreak on those who lose their jobs.

The scholarship, in other words, flows from a shareholder point of view. The ramifications considered — lower production, investment declines, financial disarray — are biased toward the organization.

In the past, many scholars have proposed using economic metrics of employee well-being to counter that bias. But even when used, those metrics typically describe that well-being as it relates to performance and productivity. Employee well-being is rarely treated as an important issue in its own right.

New scholarship, George and Dane argue, should take into account how layoffs and job instability affect employees and their families. The fear, uncertainty and deprivation that go with job insecurity often have long-term effects on the worker. They also have consequences for children, ranging from homelessness and hunger to mental and physical illness.

Gyms, yoga and juice bars all reflect the growing consciousness that the health of workers guides the health of business. But perks won’t cure the economic bloodletting related to low pay or, worse, job loss. For academics in the business of studying business, there’s far more to learn about what U.S. workers really need to be happy.

Jennifer M. George is the Mary Gibbs Jones Professor Emeritus of Management in Organizational Behavior

Erik Dane is a former professor and was the Jones School Distinguished Associate Professor of Management in organizational behavior at Rice Business.

To learn more, please see: George, J. M., & Dane, E. (2014). Taking a deeper look at hard times and worker well-being. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 7(4), 573-576.

Never Miss A Story