A Star Is Born

Consumers often react to corporations based on whether they reflect their personal values.

Based on research by Anastasiya Zavyalova, Michael D. Pfarrer and Rhonda K. Reger

Why Businesses Are Like TV Characters

- The media tend to focus their storytelling on firms that have plenty of readily available information about their identities.

- For some people, an organization’s identity dovetails with their personal identities. For others, the organization’s identity clashes with their own self-images. Because of this, an organization can experience both celebrity and infamy at the same time.

- Celebrity is harder to sustain. Infamy is harder to shed.

Everybody wants to be famous. Big corporations are no exception, and with good reason. Like any starlet, a company that’s seen as a “celebrity” enjoys all kinds of perks. That’s because the link between the firm and its customers is emotional; when a firm is a celebrity, the relationship can feel a lot like love.

A recent study by Anastasiya Zavyalova of the business school, Michael D. Pfarrer of the University of Georgia and Rhonda K. Reger of the University of Tennessee at Knoxville (formerly of the University of Missouri) reveals in new depth the advantages and limits of corporate fame.

Most importantly, the researchers write, celebrity has consequences. As soon as a firm finds itself bathed in public acclaim, it opens itself to infamy in the eyes of those who dislike the firm’s identity.

Consider 84 Lumber Company’s recent Super Bowl ad depicting a Latin American family’s struggle to make its way to the Unites States. Facing a wall at the border, they seem to have lost their dream. Then they find a wooden door and pass through it.

Viewers responded with intense approval–and equally intense hostility. “Almost lost a job for having 84 Lumber as my supplier,” wrote contractor Zack Mayberry on the company’s Facebook page. “Development told subs they could not use 84 Lumber. Spent almost 1 mil last year. Have to find a new supplier to support my needs.”

Whenever a company makes a choice, consumers are touched in a multitude of ways. Effectively, Zavyalova writes, these consumers are like political constituents. What the researchers define as corporate “celebrity” is a form of love based on the total of a company values. “Corporate infamy,” as the researchers define it, is a deeply personal rejection of a firm’s values.

It’s up to the constituents whether a firm enjoys celebrity, endures infamy–or both. A firm can pioneer a critical technical innovation, but that’s not enough to earn celebrity status: For that, it needs to take a stance on socially significant issues.

Major media create these narratives, connecting a firm’s actions with storylines that resonate for the public. By highlighting a firm’s non-conformist persona, for instance, media can present it as if it were an individual fighting for social change. Online retailer Etsy is one such company, attracting hundreds of stories about its corporate diversity ethic, from aggressively recruiting young females to insisting on a gender balanced senior team.

But the same firm that ignites fame with some consumers can stoke infamy with others. That’s because narratives with social import can fuel deeply personal, often contradictory, responses. Some consumers may feel personally attached to the firm; others will be alienated by a set of values that differs from their own. The more media attention the firm receives, the higher the likelihood that it will evoke intense feelings.

Take the example of fast-food restaurant Chick-fil-A, focus of heavy media attention for its corporate opposition to same-sex marriage and support of the “biblical definition of the family unit.” Same-sex marriage supporters responded with a wave of protests, including a nationwide boycott. As a result, supporters of traditional marriage defended the chain and its values, with nationwide gestures such as “eat at Chick-fil-A days.”

Like any media star, even the most adored celebrity firm can’t keep its sparkle without a little work. It needs to continually freshen material about its socially important innovations, just as a character in a TV series undergoes regular transformations in the course of a year. Even so, emotional traction gets harder and harder to sustain. Most television characters lose their social relevance over time; celebrity businesses do, too.

Corporate infamy, on the other hand, is the opposite: It’s hard to forget. Each new tidbit that makes people hate a brand makes it that much harder for the firm to shed a negative cast. Most firms one day shed their celebrity glow, whether they want to or not. Infamy, however, sticks like flop sweat.

Anastasiya Zavyalova is an associate professor at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Zavyalova, A., Pfarrer, M., & Reger, R. (2016). Celebrity and infamy? The consequences of media narratives about organizational identity. Academy of Management Review, doi:10.5465/amr.2014.0037.

Never Miss A Story

You Might Also Like

Keep Exploring

Road Warriors

In emerging markets, locals with experiences abroad can bring distinct advantages to business at home.

Based on research Haiyang Li, Yan Anthea Zhang, Yu Li, Li-An Zhou and Wieying Zhang

In Emerging Markets, Are Locals With Experiences Abroad Better For Business?

- People from developing countries who study and work in developed nations bring distinct strengths and weaknesses to businesses when they return home to emerging markets.

- Overall, these “returnee” entrepreneurs under-perform in terms of firm growth and survival compared to those local entrepreneurs who haven’t worked or studied abroad.

- But state ownership and firm age can mitigate the performance gap between the “returnee” entrepreneurs and local entrepreneurs.

In today’s world, people blessed with strong technical skills often move from developing home countries to more developed countries for study or work. Many later return home with burnished technical and business skills. But how do these skills translate when they start companies of their own at home?

Two Rice Business professors, Haiyang Li and Yan Anthea Zhang, collaborated with three professors in China to investigate.

To evaluate the success of companies started by locals with overseas experience, the team studied technology businesses founded between 1995 and 2003 in Zhongguancun Science Park (ZSP), China’s largest technology cluster. The team analyzed the firms’ growth in employment size, sales and profit, as well as their survival rate.

Businesses started by entrepreneurs who spent time abroad turned out to have some striking advantages — and disadvantages — compared to their homebody compatriots. In general, the returnees had higher educational levels and technical skills. For example, in the team’s sample, about 80 percent of the returnees who started new businesses had either a master’s degree or a PhD, compared to 28 percent of the non-travelers who started new companies. In these businesses, all of which are in the high tech industry, higher education levels correlated with higher levels of success.

Travel also seemed to fuel creative thinking. In ZSP, more than 57 percent of returnees held one or more patents. Because of their exposure to the high-technology markets in both developing and developed countries, the returnees could spot and exploit technological gaps. These gaps often provide opportunities for innovating and for building new companies in an emerging market.

But the advantages of education and work abroad came along with drawbacks. Like Rip Van Winkle, returnees often find that vast cultural shifts have occurred in their absence. They may no longer understand how their home country’s market works, or be stymied by an emerging market that operates differently from the developed markets to which they’ve grown accustomed. While abroad, moreover, they may have lost chances to nurture local contacts and business connections. For a new business, a lack of local knowledge and connections can be hobbling.

There are ways to compensate. In China, the researchers found, partnering with government is especially powerful. When the government has controlling interest in a venture, the returnee owners enjoy much improved access to key resources and connections.

Partnerships between government and returnees also have a salubrious effect on a venture’s overseas business. International suppliers, customers and other potential partners often distrust government-owned companies. These stakeholders may have greater confidence in business leaders who have lived and worked in a developed market environment, and know the rules of the road. This familiarity allows returnees to collaborate more effectively with the overseas stakeholders, strengthening trust. And trust is good for business.

Along with government affiliation, a firm’s advancing age can also work in favor of returnees. As a venture ages, it builds its own track record and business relationships. The more local relationships the venture creates, the less important its initial lack of local relationships becomes.

In China as in the United States, experience abroad seems to fuel innovation (the majority of new patents granted in the United States include a foreign-born inventor). But as in any country, business connections count. The trick for ambitious technology workers from the developing world is to amass a repertoire of overseas skills, education and cultural expertise — and persuade their own governments of its value.

Haiyang Li is a Professor of Strategic Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Yan Anthea Zhang is a Fayez Sarofim Vanguard Professor of Management in Strategic Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Li, H., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Zhou, L., & Zhang, W. (2012). Returnees versus locals: who performs better in China’s technology entrepreneurship? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 6(3), 257-272.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Making Converts Of Consumers

Religion has been marketing itself for millennia; now businesses are borrowing its techniques.

By Utpal Dholakia

Religion Has Been Marketing Itself For Millennia; Now Businesses Are Borrowing Its Techniques

It may sound like sacrilege to some, but Rice Business professor Utpal Dholakia argues that the same principles that have drawn people to organized religion can, and have, been used by marketers to draw people to their products.

The following originally appeared in the Harvard Business Review online.

Organized religion has shaped virtually every aspect of human behavior for thousands of years. Some historians have even argued that religion was integral to human survival. Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that savvy marketers have figured out that they can use some of the same basic principles to connect with their customers – and that brands have taken on such importance to consumers.

And yet the narrowly formulated, self-serving, and consumption-focused beliefs and values, rituals, and communities provided by brands usually have little to offer beyond the boundaries of their products and services. Thoughtful marketers should have an understanding of how this is shaking out – how some brands are adopting the characteristics of organized religion – so they can think critically about whether this is something they want to do.

Scholars have found that every organized religion offers three key benefits to its followers, a) a set of core beliefs and values, b) symbols, myths, and rituals, and c) relationships with members of a likeminded community. Here are a few of the ways in which brands have begun using these elements to create “congregants,” not just customers:

- Core beliefs and values. The essence of any religion lies in a set of beliefs and moral values. Just consider how fully many of us embrace precepts such as “Impossible is nothing,” “Challenge everything,” or “Make the most of now.” Each of these slogans sounds inherently good, worth adopting and even building our lives around. Yet their origin is not some divine revelation or millennia-old discourse, but the minds of clever copywriters. Also common to every religion is belief in a divine, benevolent, supreme being. And today, figures like Jeff Bezos and the late Steve Jobs have been described as our “saviors” in how they’re portrayed. For instance, when Mr. Bezos purchased the Washington Post in August 2013, many media experts called him “journalism’s savior.” And the international edition of Fortune magazine recently depicted Bezos as the Hindu god Vishnu on its cover. Stories about the magnetic, larger-than-life founders of Amazon and Apple provide a rich mythology that draws consumers to these brands.

- Symbols, myths, and rituals. Rituals are repeated behaviors that follow a script and possess symbolic meaning. Over centuries, people have practiced religious rituals to mark rites of passage such as birth, marriage, and death, to mark certain times of each year like the end of the harvest season, to please divine powers, and to ward off misfortunes. Rituals impose order and structure to our lives, and assure us about our place in the scheme of things. While we continue to follow many rituals established by religion ― wedding vows or the Thanksgiving meal, for instance ― we have also adopted many rituals associated with brands. Activities like a particular way of eating an Oreo cookie (twist, lick, then dunk), participating in the “VW wave” (waving to another Volkswagen Beetle driver to say hello and signal solidarity), or using special, made-up words like “Venti” or “Frappuccino” at a Starbucks store every morning provide some of the same benefits as religious rituals do. Consumer psychologists have shown that creating new rituals for customers is a great way to heighten their enjoyment and to build strong brands.

- Relationship with a community. Through the ages, religious life and social life went hand in hand. People belonged to the same religious congregation their entire lives, and relied on fellow members for companionship, financial assistance, and social support. They found their friends, well-wishers, and spouse, and socialized their children there. Today, brand communities, fan clubs, and social networks provide many of these same benefits. Many motorcycle enthusiasts spend their weekends and vacations with their Harley Owners Group at rides and rallies. In user forums and chatrooms of companies like Hewlett Packard, Microsoft and Texas Instruments, tech enthusiasts devote hours upon hours helping others solve their problems without pay. Brands like Jeep, the Russian camera maker Lomo, and Samuel Adams organize “Brandfests” to bring together customers for enjoyable and educational experiences. In such venues provided and managed by brands, people socialize, form friendships, and even romantic relationships.

On one hand, it’s easy to see why these powerful tactics would appeal to marketers. On the other, as consumers, worshipping an iPhone or a Tesla cannot teach us to be happy or content with our lives. Nor can a Harley Owners Group necessarily provide us with the genuine friendship and intimacy that a caring spouse, life-long friend, or neighbor can. So as shoppers, we may be best served by enjoying the benefits that brands provide, yet acknowledging there are limits. And as marketers, we might want to ask ourselves if the value of what we’re selling lives up to our power to sell it.

Utpal M. Dholakia is a professor of marketing at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University. This story appeared in the February 18, 2016, online edition of Harvard Business Review under the title “Brands Are Behaving Like Organized Religions.”

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

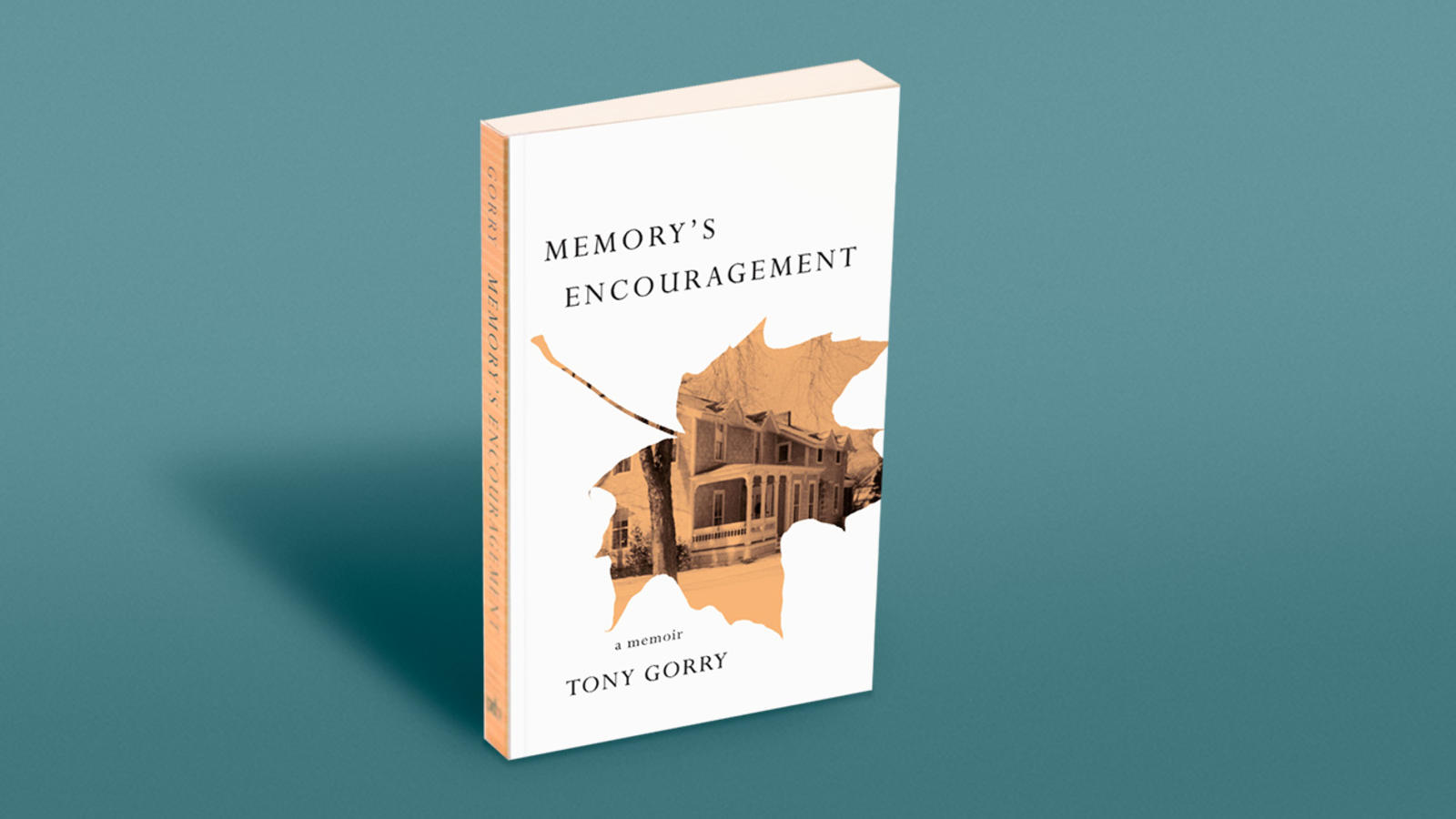

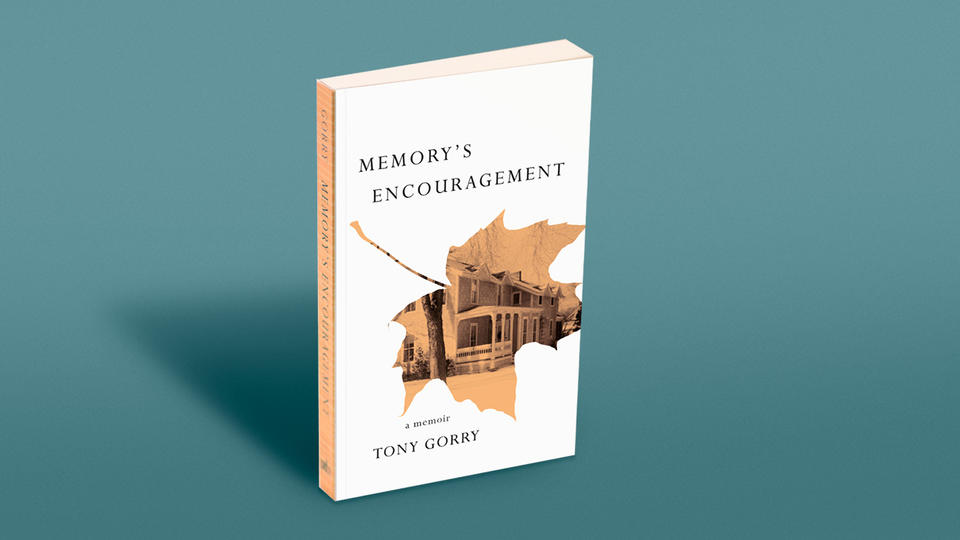

Memoir

Read an excerpt form Tony Gorry's book, Memory's Encouragement.

By G. Anthony Gorry (1941-2018)

Rice Business Professor Tony Gorry Journeys To His Past And Discovers That Memory Offers A Powerful Lens For Viewing The Present

Memory’s Encouragement, by Tony Gorry, the Friedkin Professor Emeritus of Management at Rice University, was published by Paul Dry Books, Inc. 2017.

Among My Souvenirs

I was running errands and, needing directions, I called up my car’s navigator. “Turn left at the next intersection,” she guided me; “proceed one-half mile.” After shopping, I pressed the icon for my home. As my digital companion chimed in, I said, “Wait, I don’t need your help to find my way back.” Talking to a machine is something I do often these days. I closed the display. “Certainly I can remember where I’ve been.” True in this case, but would I always find my way back home?

This talk with my machine made me think of another trip, one almost eight years ago: a return to my hometown to attend my fiftieth high-school reunion. My sixty-eighth birthday had been approaching, and the tug of nostalgia drew me back for the first time since that graduation. In anticipation, I rummaged through the contents of an old shoebox that had languished in the back of a closet for years. It held a motley collection of photographs, yellowed newspaper clippings, school programs, awards, and an old Bulova watch my father bought for me after he returned from the war.

The shoebox was a welcoming gateway to another country rich in presence. I felt immediately reconnected to places I’d lived and left long ago. My past emerged to prepare me for my homecoming.

I was struck by the way in which memory transformed time and space. I was there at my desk in 2008, but I was also in the world of my youth, many miles and decades away. I held a photograph taken at my grandmother’s house, where I had lived while my father was fighting in Europe. It was probably 1944, and there I stood, almost four years old, with my wagon on the front porch. Though the picture was black and white, I knew that the wagon was red; my coat, blue; its six buttons, shiny brass. I could nearly smell the cool air of that spring day when sun-dappled snow still covered much of the ground.

In moments like this, I imagine myself a wanderer, one who has hurried along earlier pathways and now nears the end of his journey. I move more slowly, I take more breaks to ponder where I’ve been, to reflect on beautiful vistas of the past as well as rocky stretches, slippery crossings, and my wanderings off course— and the people I have met along the way. Remembrance pushes the present aside.

In a bookcase by my desk I have a copy of Homer’s Odyssey, the story of another homecoming. With its nymphs, goddesses, and monsters, the epic is a catalog of delights and wonders. It is also an account of a harrowing voyage through danger, terror, and gloom. Odysseus has plundered the stronghold on the proud heights of Troy, and now Poseidon, enraged most recently by Odysseus blinding Polyphemus, the cyclops, resists the hero’s return to Ithaca, where his wife and son have awaited his homecoming for twenty years.

Though my homecoming little resembled Odysseus’s heroic journey, one of his encounters reminds me of our life in the digital age. During the penultimate leg of his journey, when Odysseus is adrift at sea, Poseidon blasts his raft. Clinging to wood from the wreckage and barely escaping drowning, Odysseus washes up on shore, naked and exhausted. After a night’s sleep, he awakes in confusion. What place is this? Who lives here? How will they receive him?

His questions are answered when he meets Nausicaa, the daughter of the king in this land of Scheria. It is, she says, a place distant from other lands. Its inhabitants, the Phaeacians, are dear to the immortal gods. Indeed, the Phaeacians often encounter Olympians strolling in their midst.

Concerned that she might be seen unchaperoned with a naked stranger, Nausicaa sends Odysseus on alone to her father’s palace. There Homer reveals an otherworldly stamp on Phaeacian buildings and crafts. The palace is a marvel, airy and luminous, with the luster of the sun and moon. Bronze-paneled walls with azure moldings of lapis lazuli lead to the reception hall where the post and lintel are silver on silver and where gold handles curve on the doors. The entrance is flanked by hounds sculpted from silver and gold. Odysseus learns that Poseidon has made the Phaeacian ships as “swift as a wing or a thought.” They need neither pilot nor rudder to travel miraculous distances and still return in a single day.

A large garden fronts the Phaeacian palace. There the interpenetration of the heavenly and the mundane is striking. Apples, pears, figs, olives, and grapes grow profusely, giving their bounty regardless of season. As he scans this wondrous garden, Odysseus sees clusters of green grapes, others still ripening on the vine, some drying in the sun, and still others being crushed for wine. While currants dry in one part of the garden, vintners tromp purple grapes in another, and in yet another the new grapes are just losing their blossoms. It is not only the materiality of Scheria that has been touched by the gods. Time, too, has been transformed. In this garden the past, present, and future commingle. Yet despite these marvels, nostalgia retains its grip on Odysseus. He yearns for Ithaca, his wife and son.

The Scherian garden may be just poetic fancy, but my garden of the past is unworldly in its own way. There I cultivate remembrances and shape what I know about the past. In reverie I construct personal edifices, some gleaming, others shadowed. In memory, what was long ago can suddenly be close at hand; what was far, now near. A strange garden, with its own strange physics, but one I lately tend with care, for its produce enriches and encourages me.

Tony Gorry was the Friedkin Professor Emeritus of Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Textbook Case

Is it time to treat corporations’ political activity as an academic field?

Based on research Douglas A. Schuler, Kathleen Rehbein and Colby D. Green

Is It Time To Treat Corporations’ Political Activity As An Academic Field?

- Corporate political activity looms increasingly large on the U.S. landscape.

- Events in the market, including China’s increasing heft as an economic power, suggest rich areas of research that could one day make corporate political activity its own academic field.

- Even so, research into this activity hasn’t emerged as a distinct field.

Companies’ efforts to yank the levers of power are drawing intense scrutiny. Growing populist movements question corporate sway in citizens’ lives, while the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in "Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission" has loosened government reins on corporate political giving. Even before assuming office, the Trump administration did not hesitate to intervene in corporate decisions about where to source production or how to price multi-year governmental procurement contracts – choices that clearly could reverberate politically.

But does this activity merit its own academic field? Not yet, according to Douglas A. Schuler, a professor at Rice Business, Kathleen Rehbein of Marquette University and Colby D. Green, a Rice doctoral candidate.

Corporate political activity, Schuler, Rehbein and Green say, is any effort by firms to sway public policy to advance the firms’ market goals. Firms might do this individually or via industry trade groups through lobbying, political contributions or testimony at public hearings that bear on their business.

The framework for the trio’s research is a 2008 study by D.C. Hambrick and M.J. Chen, who identified three traits fundamental to an academic field. These are differentiation from other disciplines, mobilization of the supporters of the discipline and legitimacy of the discipline to those outside it.

To reach their conclusion about corporate political activity as an academic field, the researchers looked at several metrics associated with those three things. Among them: course requirements for students working toward masters degrees in business administration; conferences and scholarly communities on corporate political action; and views about the publications devoted to the topic.

The results spoke volumes.

Researchers studying corporate political activity do ask questions that other disciplines don’t, Schuler and colleagues found. And their lines of inquiry distinguish them from scholars in related fields such as management, economics, political science and sociology.

Researchers in other fields, for instance, have studied how corporate political activity affects public policy. Specialists, in contrast, look at the motivations for that activity. One such paper shows that corporate political involvement rose after firms proposed mergers that needed regulatory approval.

At the same time, business school leaders say that articles in the two journals most specialized in addressing corporate political action don’t count for much when they assess underlings who must publish to advance their academic careers. There’s also a relative lack of corporate political action research in more established management and strategy journals.

Back in the classroom, of the MBA programs at the top 20 business schools ranked by Bloomberg Businessweek, only four – Harvard, Stanford, Yale and Rice – require courses in corporate political activity. Most other schools on the list offer the topic as an elective.

Similarly, the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International, an accrediting agency, lists courses that tackle corporate political activity as central to graduate management programs. But it doesn’t go as far as to label the topic a unique field.

Applying these findings to their framework, Schuler and his colleagues conclude that as an academic field of study it still falls short.

They see opportunities for fostering deeper interest, however. China, in particular, provides plenty of fodder for research into the intersection of company and government behavior. The topic is increasingly pressing with the growing international market strength of Chinese companies under a state-centered, authoritarian government.

But Schuler’s group also notes that the birth of any new discipline has its own political component – inside academia. Any time a new field emerges, it can siphon attention and funding from existing disciplines.

There’s no question, in other words, that the U.S. and international political environments offer rich material for the examination of corporate political activity. But at least for now, specialized study of this topic must remain in political campaigns, governmental offices, news shows and editorial pages. The academy will have to wait.

Douglas A. Schuler is an associate professor of business and public policy at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Schuler, D.A., Rehbein, K. & Green, C.D. (2016). Is Corporate Political Activity A Field? Business & Society. 58(7) 1376–1405

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Curiosity Shop

Food means belonging and feeling of home in immigrant business.

By Claudia Kolker

Food Means Belonging, Home In Immigrant Business

How can a small, cluttered, seemingly out-of-date business survive in a neighborhood rapidly transitioning from working- to middle- and upper-middle class? Speaking to writer Claudia Kolker, Rice sociologist Stephen Klineberg explains: In its own way, that business reflects the essence of Houston entrepreneurship.

Wedged into a narrow space on Richmond Avenue, a tiny, chaotic shop called Variedades Puebla peddles snacks not easily found in most other stores. On the counter stands an irregular triangle of cheese, transported by hand from Oaxaca; in the refrigerator sits a blood-red hunk of mole, cooked with five kinds of chile. And on a little wooden shelf near the chips, rolled plastic bags hold desiccated brown shards that, on inspection, turn out to be edible crickets.

Almost unbelievably, Variedades Puebla has sold its wares in this spot between Hazard and Woodhead for 23 years. It has survived as townhouses leapt up blocks away; stood firm when Fiesta went dark in the shadow of the lavish new HEB. Segway dealerships, trendy restaurants, and mattress stores have popped up and vanished, but Variedades Puebla has not moved.

It would be easy to imagine that the shop reflects some otherworldly pact to never change. But in fact it represents just the opposite. Variedades Puebla is an example of knowing the right time to change, and knowing just how much change is enough. It's a triumph of Houston entrepreneurship.

Plastered with signs for check cashing, bill paying, remittances, and "Gelatinas de Piña y Naranja $1," Variedades Puebla’s façade gives its first, lively blast of Mexican aesthetic. Inside, every corner echoes the same note of abundance. On the right, under a line of soccer jerseys, shelves are crowded with purple and red-plaid brassieres. The glass counter is packed, above and inside, with watches, wallets, greenery, bags of chopped cactus paddles, and paper-wrapped stacks of tortillas rolled off the belt that morning from a Long Point factory.

Toward the back, an uncovered cardboard carton offers grayish sheets of dried beef; beside it, another box holds a soccer ball swathed in plastic and a sac full of dried chilis. On a shelf near the dried crickets nestle small plastic bags packed with dried shrimp, tiny dried fish for munching, dried cilantro, avocado leaves for tea, and little balls of dried pepper. On the floor, in front of the counter, a crate of onions lies next to a crate of plaid shirts for little boys.

"I've come to pay my electric bill," a burly Mexican man in a blue T-shirt says, approaching the counter. The shop's aisles are so narrow that the man would be hard-pressed to navigate them if he wanted to shop for food. But at Variedades Puebla, services such as utility payments are as much of a draw as the pan dulces and crickets.

Parked behind the counter in a spot crowded with fax machines and other electronics, owner Saul Vivas is a friendly man with an impish, Cantinflas mustache. Originally from Puebla, Mexico, he moved to Houston with his mother when he was 14. For years, they lived in a humble apartment at Welch and Dunlavy. Vivas learned excellent English; went to Lanier Middle School; then, soon after high school, deployed his charm and language skills as a waiter at River Oaks Grill. In 1992, he gathered his savings and struck out on his own, first with a taco truck on Bissonnet, and finally by launching Variedades Puebla – the last part of the name reflecting his heritage, and the first the variety of offerings.

"I wanted to be independent," Vivas says. "I didn't want to rely on a boss.''

The time was the early 1990s, and it was clear what the market would bear: decked with a prominent sign offering "Fashions," Variedades Puebla offered specialized clothes to the recently arrived immigrants from Mexico and Central America who populated the apartments up and down Richmond. These newcomers, Vivas knew, didn't have the money to shop on West Gray or at the Galleria. Plus, he knew what rural immigrants liked: cowboy hats and boots, brown-and-white embroidered belts, and soccer jerseys – stacks of soccer jerseys, with the names of home states and beloved players. The newcomers also craved music from home. Vivas stocked whole aisles of CDs, with lots of Mexican pop, and almost as much from traditional genres such as charro songs.

The store never grew—physically it couldn't—but its location was key to its success. Montrose was gentrifying, but this patch of Richmond remained hard-scrabble: decayed brick buildings and small apartment complexes housed a constant tide of newcomers who washed dishes and bussed tables in area restaurants. Many did without cars.

“There aren’t very many who stay in these apartments,” Vivas says. “They earn money, buy a house, and move. But there are always new people from Mexico – now, more than ever.”

For years, the Fiesta at Alabama and Dunlavy appealed to these shoppers by offering Spanish-speaking attendants and shelf after shelf of chilies, tamale husks, and tamarind candy. Variedades Puebla supplied clothes and music.

But gradually the tides of business changed. "I used to be the only place for the new people from Mexico to buy clothes," Vivas says. "But then it became possible to buy clothes very cheaply from Asian businesses in the Harwin area."

The CD business tanked too. As the Internet blossomed, even the least educated rural immigrants learned how to download songs online, or find links to their familiar music for free. The clothes-and-music business looked dire. Then, auspiciously for Vivas, the Alabama Fiesta closed.

Across the street, a bigger and even more abundant store rose: a wood-paneled HEB, as elegant on the outside as it was chic on the inside. But the dishwashers who lived in the $700 a month complexes on Richmond had little use for chic. They needed ancho chilies and Mexican aspirin. They came to Vivas and asked, could you get hold of those?

He didn't need to be asked many times. In 2012, Vivas transformed his store. Out went most of the clothes. The traditional CDs got nudged to a corner. After two decades, Variedades Puebla is, if anything, now more Mexican than ever: low-key, jumbled, cozy, and jammed with the snacks, sounds, and aromas of another place and time.

"Weight Loss!"

"Diabetes!"

"Energy!"

The handwritten cards trumpet their optimism from a stack of Mexican naturopathic remedies piled on the counter. In front of them stands a plastic jar full of minuscule Chiclet packages. Not as juicy, long lasting, or bold tasting as recent gum innovations, Chiclets nevertheless are unbeatable if you crave a taste of Mexican childhood.

And that, Saul Vivas says, is the reason many of his customers come to Variedades Puebla. The closing of the Fiesta created a demand for more Mexican foods, but Variedades Puebla is not much bigger than a package of Chiclets, so it only offers three or four items, in just one brand, of laundry detergent, canned beans, or corn husks for tamales. Immigrant customers pop in for supplies because they can walk to the store, but they must figure out how to get fresh produce and bulk items somewhere else.

The store’s apparent disorder, Vivas' daughter Monica says one afternoon, isn't really an accident. "My parents aren't trying to forget where they came from," she says from a seat behind the counter. Now a 21-year-old accounting student, she has been hanging around Variedades Puebla since babyhood. "Their store," Monica says, "looks and feels like back there."

Her father agrees. "A lot of our customers just come in to say hello or to be here," he says. "They don't speak English and they feel uneasy in a big store like HEB where they can't communicate. In fact many of them don't even speak Spanish. They're from Guerrero or Oaxaca, and they speak indigenous dialects. I don't speak those languages, but I listen and to try help them. So they feel comfortable here."

Chaotic as it seems, Saul Vivas' market embodies Houston-style entrepreneurship, says Rice University sociologist Stephen Klineberg.

"Food is such an important part of immigrant culture, the sense of well-being and belonging, being able to recreate home," Klineberg says. "And adapting to the changing market is so typical of Houston: that can-do spirit, and precisely that idea of figuring out how to make it work."

Even in a community constantly in flux, Vivas' attentiveness has woven strong bonds. "There's one old man who always wears a work shirt, and he treats my brothers and me like we are his own children," Monica says. "So he comes in, he talks to us, he asks how we are. He doesn't have a family of his own here. His wife lives in Mexico, but people just get used to having their families there and sending money to them."

"They're simple people here," agrees Edmundo Hernandez, 49, munching from a bag of chile-lime wheat chips he's just bought. Hernandez lives in Spring Branch, where he works as a graphic designer. But he drives to Montrose once a month to get his hair cut at the Mexican place next door and shop for Mexican snacks at Variedades Puebla. "I want to buy here, because no one looks at you strangely," Hernandez says. "You get accustomed to the service. You feel relaxed."

This story originally appeared on the Montrose Management District website, under the title “Value in Variety: Variedades Puebla Finds Its Niche Bringing Mexico to Montrose.” Photography by Juan Islas.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Meetings Of The Bored

Are we are paying too much to quell our fear of boredom?

By G. Anthony Gorry (1941-2018) and Robert A. Westbrook

An Active Mind Isn’t Always The Best One. Sometimes It Takes Boredom To Bring On Brilliance

This article by Friedkin Professor of Management Tony Gorry and the William Alexander Kirkland Professor of Business Robert A. Westbrook originally appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of the Rice Business Magazine.

In every age, leaders of businesses have encountered obstacles on their paths to success. Often changing circumstances have thwarted previously prepared plans. Then, the work of the mind took precedence over that of the hand. New ways were needed to prosper in changing competitive environments. Sometimes a single, grand conception restored a company to prosperity; other times, it was a number of lesser ideas knitted together fortuitously. Hope for such innovations rested largely on the creativity of executives.

A prominently placed "suggestion box" acknowledged that good ideas might come from workers whose job descriptions said nothing about innovation. Indeed, two decades ago, when the concept of intellectual capital first entered the management literature, journalist Thomas Stewart took it as the "sum of everything everybody in your company knows that gives you a competitive edge in the market place." In this view, what a company knows emerges not just from its leaders, but as well from the experiences, insights and intuitions of a wide range of employees. Everyone is a potential source of innovation.

So in recent years, businesses have launched comprehensive programs to tap the collective brainpower of their employees. Attention is paid to the insights of the worker on the shop floor, the customer representative, the logistic team, which had for long escaped recording and cataloging. Networks linking workers and processes across different companies undergird many recent increases in productivity, rewarding businesses that know what they know — and know it right away.

That we are attached to information technology is readily apparent to even the most casual observer. It permeates our lives and shapes much of our experience of the world. Less apparent are ways in which our intimacy with these machines is changing us.

We might expect, for example, that our growing intimacy with digital machines will swell an electronic suggestion box to foster innovation and promote organizational growth. Perhaps, but we have our doubts.

Wander the hallways of a large business. Look for contributors to our imagined suggestion box. Here's a meeting in the executive suite. See heads bowed as though in contemplation. Perhaps they're pondering strategic challenges facing the company. More likely, they're eyeing their personal digital assistants, checking email, the latest news, Facebook or Twitter. Some may think they're concealing their dalliances in the virtual world. Others, avid users themselves, know what's going on. Their attempts to hide their distractions are often half-hearted.

On the floor below, we pass several employees unwrapping sandwiches for a quick lunch. They plan to review progress on a task force report. Again, heads are bowed. Are they saying grace over their food? More likely, like the executives above, they're turning to smart devices for engagement, tuning out colleagues.

Walking on, we ask our host about the company's recent activities. While she gives us an overview, she too checks her smart phone, almost as if she needed a script for her answers.

She seems distracted. Maybe she's already devoted enough time to us and needs to get on to more important matters.

Sherry Turkle says "talking to each other is perceived as exhausting, and we happily retreat into worlds where we communicate only with machines." Maybe we're exhausting her.

At times, everyone has wished for escape from the here and now. Doodling, gazing out the window, empty-headed nodding or long, pregnant pauses: All are ways to check out of dull, uninspiring encounters. Digital technology, however, has greatly expanded the opportunities for flight. Throughout the organization, as in social life generally, its widespread use has altered the rules of civility. Device at the ready, we put our colleagues and family members firmly on notice that we won't tolerate boredom to the degree that was once expected of us.

Boredom is a cloud to be banished as quickly as possible. Our mobile devices stand ready to suppress even its most wispy beginnings. In lines, at street crossings and in waiting rooms, wherever there might be a break in life's action, shorter and shorter intervals of time now demand filling. Something may have just happened to someone, somewhere. We check and check again. We flee our own thoughts to entertainments fashioned by others. But a flight from boredom can be a flight from creativity, because it is from boredom that new ideas and connections emerge, in the executive suite and on the shop floor.

What of our imagined suggestion box? Its value depends on contribution, assessment and dissemination. First, managers and workers need to volunteer insights regarding their jobs and improving the performance of the business. Next, from those contributions must be selected knowledge and practices that most promise benefits, grand or small. Finally, the chosen innovations must be shared and improvements must be anchored in the ways of the company.

Failure in any of these steps locks creativity within one part of the organization, unrecognized and unexploited by others. Too often then, errors will be repeated; opportunities, lost; and innovations, unrealized. Even strategic opportunities may be foregone.

What of those we've just seen in our walk through the company? Their devotion to machines makes them uneasy in life's slower moments. Those who are uncomfortable with boredom may contribute less to the company's intellectual capital. When we tap the suggestion box, we may find its contents have dwindled.

Although boredom has been a concern of philosophers and scientists for ages, its nature and cause remain elusive. Boredom may arise from an existential perception that life is empty. Psychologists and social scientists have found that commonly and less dramatically, we are bored when we judge an activity unworthy of our attention. Tasks that are too simple allow attention to wander, creating dissatisfaction with the job at hand. For ages, meditative teachings have countered such boredom by avoiding judgment of the worth of activities. For most of us, however, parental advice ran in a different direction: "Find something to do!" But finding too much to do may also induce boredom, because attention is pulled in too many directions. Then we need to step aside, to do less, to reflect.

In the 1800s, Charles Baudelaire confronted a new Paris thrust up in the midst of the old by commercialism. Most startling were the throngs in the streets, the plentitude of the marketplace and the new architecture of the city. How should a thoughtful person manage interactions with such a myriad of people and things? The crowd offered spectacles and enticements, often quite unexpected, as Baudelaire describes in one of his poems. A woman passing by briefly intoxicates him, but he cannot know what path either she or he would follow into the future. She was just one of some many brief experiences: accidental, anonymous and transitory to be encountered in the tumult of the new Paris.

Baudelaire felt the onset of a new kind of boredom induced by an acceleration that threatened to make life just a series of fleeting impressions. He said that of the "squalid zoo of vices" that plagued his time, boredom "is even uglier and fouler than the rest." It would gladly swallow all creation in a yawn. In the face of restless activity and frightening anonymity, the wanderer was always on the lookout for novelty of experience or observation that would penetrate the fog of the teeming crowd and restore him to life. But each new event or encounter, which promised so much, proved just as empty as its predecessors.

Much the same could be said of today, although we more often wander electronic byways rather than cobbled streets. In the burgeoning crowd of cyberspace, we are dissatisfied with our situation and wish to be elsewhere, doing something different. We could turn away from the distractions of our bustling electronic byways, but such a departure seems to demand more energy than we can muster. Even when we take such a break, we may find we've forgotten how to be comfortable with ourselves. Something deep within urges us to rejoin the crowd.

Today's world of tweets bears vestiges of the long trek our ancient ancestors took to become human. Along the way, emotional sensitivity to others was joined by strong curiosity about them, a desire to know what they were thinking, feeling and scheming. Once we became capable of creative reflection, we no longer had to satisfy this desire in actual social situations; we could find pleasure in imagined activities and interactions. In today's fluid electronic arenas for gossip, preening, and posturing, users "strut their stuff" with embellished self-descriptions and accumulations of "friends" from far and wide. Scores and stars announce prowess. These designations would mean little, had evolution not made us so drawn to groups, so sensitive to trappings of rank, and so irresistibly drawn to judge and categorize others. Our brains hunger for participation and status, and our smartphones and tablets stand ever at the ready to feed them. We love these devices, because we were born to love them.

In an old vaudeville act, a man set plates spinning atop a row of poles. Back and forth he hustled from one pole to another, giving each just enough spin to keep its plate from falling. As he attended to one plate, others teetered precariously. Too much attention to one meant disaster for others. Not enough meant that this one would fall. Success depended on giving to each pole just enough attention to keep its plate aloft. As he went, an assistant added new poles and plates, demanding even more speed from him. He had to conduct the remainder of his act on the dead run.

Our plates and poles today are digital messages. Work, home, social networks all clamor for our attention. Proud of our ability to sustain the pace of life in the digital age, we race from email to cell phone to computer screen, spending enough time on each task only to keep it spinning. We even add new poles as we race along.

The two of us, who have been around for a while, no longer make good vaudevillians of the plate spinning kind. The pace has become too swift. We need some proverbial peace and quiet.

But what of the many others, who are unnerved when life slows and not much seems to be happening? It isn't crashing plates they fear. It's spending too much time on one thing when something else might be happening.

They take boredom as a signal to move on, to focus attention on something else. For many, that feeling arises ever more quickly. Students, who once happily watched a five-minute video in class, now get itchy after a minute or so. News stories are compressed. Executives want complex matters reduced to bullet points for quick consideration. Consumers choose movies, restaurants and books on anonymously awarded stars, because who has the time to read up on these subjects? It's so boring.

In today's fast-paced life, we could have the time to read, ponder, investigate and slog along. Absent the sirens of digital technology, perhaps we might do so. Reading makes many uncomfortable, when, for example, long sentences with subordinate clauses run on for more than a line or two, describing situations or putting forth arguments, which well may be central to the subject being written about, but as they proceed, seem to test our powers of concentration, which have been tuned by the terse text of instant messaging where compression of language and perhaps of thought hold sway. A vaudevillian living in a world of hyperlinks and bullet points reads the first of the previous sentence and mutters, "Oh, get on with it!" and jumps to an email or text message that might be more "interesting." We want at most the general idea, to learn just enough, just in time.

Walter Benjamin argued that a story claims a greater place in our memories when the teller allows us to embellish it for ourselves. The more we integrate the story into our own experiences, the greater will be our inclination to repeat it. In the retelling, it may assume new and deeper meanings. This is true not just of stories told by others, but of those we tell ourselves. Tennessee Williams claimed "that life is all memory, except for the one present moment that goes by you so quickly you hardly catch it going? It's really all memory . . . except for each passing moment." Quickly we weave moments of an experience into a story, however brief, which embodies our memory of it. In reminiscence, we return again and again to inspect, edit, and embellish the story. In making plans, we may intertwine a variant of the story with imagined acts in and imagined history of the future. Unless we simply copy someone else's story, we need inspiration to write our own. But the assimilation of a story requires a state of relaxation, which even before the Internet era was becoming rare.

Benjamin said boredom is the apogee of mental relaxation. The self-forgetful listener who puts aside the press of life and attends deeply to his memory prepares the nesting area for the dream bird, Benjamin's metaphorical bringer of insight and understanding. In quiet disengagement from the bustle of the world, the dream bird hatches the egg of experience.

Many of us could benefit from this bird's visit, but we need "down time" to welcome it in.

Today, however, our machines are always at our side, to fill that quiet time. We push letters onto a Scrabble board, fight off attacking aliens or draw pictures for another to guess.

Enticements delivered to cell phones demand attention that once would have been devoted to the meeting agenda, the dinner companion, the teacher or even reverie. They rustle the leaves and drive the dream bird away.

Enthusiasm for these simple games underscores our brains' need for engagement and status. Points or promotions, stars or scores assure us of our skill and pats on the back keep us going. If we don't feel competitive, there are other applications that promise tidbits of information as tokens we can collect. What is the current temperature in Paris, the score of the Yankees' game, the change of a stock price from ten minutes ago? We ask these questions, not because their answers are important, but because they can be answered by our digital devices. They give an immediate purpose, however small, to idle time. Each reward is a note in a siren's song that draws us ever deeper into technology's domain.

Digital distractions will proliferate. Many presently inert objects will become interactive. Perhaps our cereal boxes will challenge us to a simple guessing games at breakfast: win points for the next trip to the market by ranking food combinations by calories. Think of all the places that have already been invaded by advertising. To imagine a likely future, think of many of those sites as places for games. Idle moments in which we could reflect on what has happened to us, what we have done, and the interactions we have had with others — those moments will be increasingly filled with imaginative engagements with the virtual. The dream bird will get chased away by a call from a cereal box.

To quarrel with technology is to quarrel with human nature. Our intimacy with machines will increase. So what of boredom? Inherited urges may incline our behavior, but they need not determine it. If, fearing moments with nothing to do, we turn to machines for constant entertainment and engagement, we will lose time for invention. If we don't pause between tasks to reflect on our lives, we may not know where we are or where we are going.

Instead of fleeing seemingly empty moments, we should welcome them in moderation. Indeed, we should create times of solitude in which we plan to do little. Creativity is the residue of time wasted, Albert Einstein supposedly said. But how do we find time for "doing nothing" in our economy of speed and efficiency? When everyone else is working "leaner," isn't it unwise to indulge in reflection that can't be easily monitored or measured? Our quick answer: don't bet everything on the hare; wager a bit on the tortoise. Put aside the machines we love — at least for a time.

Recently, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Matt Richtel reported on a rafting trip taken by five neuroscientists in a remote area of southern Utah. They sought to understand how intense involvement with digital devices changes how we think and behave. Would a retreat into nature reverse any adverse effects?

They went off the grid, leaving laptops and cellphones behind. As days passed, the time of the wilderness supplanted that of the digital world. Conversations were interspersed with periods of silence in the presence the wonders of the surroundings. As the river flowed, says Richtel, so did ideas.

One of the travelers noted that, "the real mental freedom in knowing no one or nothing can interrupt you." We suspect Einstein would have concurred. Benjamin was no scientist, but he would have stood well in that company. Be quiet and wait. Be bored. The dream bird will come.

Think of the future time as a wilderness, and you as its steward. Of course, you'll allocate significant parcels to industry — to activities appropriate to your work and home life. Some of that space, however, should be reserved, much as the Utah backcountry, where the ways of life are slower and less congested. Preservation requires vigilance and determination. Once, for example, vacations meant time away, time without the interruptions of everyday life. Traveling in a car or plane offered shorter versions of the same. Now, like developers falling on pristine land, smartphones and wireless networks have colonized that time. They have bought their way in by feeding our brains' voracious appetites for stimulation.

Writing, printing, the cinema, television and other precursors of our inclusive cyberspace substantially changed how we gather and share what we know. They disrupted long-standing social structures and expectations of personal behavior. While life is not determined by technology, each of the innovations, which now seem a part of the natural world, exacted a price. In dealing with our smart devices, we need to take a stronger negotiating position.

We are paying too much to quell our fear of boredom, too readily yielding our refuges to the rush of the now.

We should protect segments of time, putting smartphones and tablets aside, leaving our desktop computers. Just sitting, walking, gardening, talking with friends: these are but a few ways to enter our own personal wilderness.

When we slow down, we may at first be bored, but soon, we are apt to find much to do. Perhaps the dream bird will come, bringing us a new addition for our organization's suggestion box. Or perhaps something just for us. Even if it doesn't, we are likely to return to the rush of the digital age with a better sense of who we are — and who we want to be.

Tony Gorry was the Friedkin Professor Emeritus of Management at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University and Robert A. Westbrook is the William Alexander Kirkland Professor of Business at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Thinking On Their Feet

If sitting is the new smoking, has standing made a stand?

If Sitting Is The New Smoking, Has Standing Made A Stand?

Wherever you weigh in on the hazards of sitting vs. standing all day or alternating between the two, there’s no denying that standing (and also walking) desks are populating offices everywhere, even McNair Hall at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

An informal poll of faculty at the business school revealed different reasons, from health to height to hoping for increased productivity. Here’s what the research is telling us:

Ben Lansford

Director of the Master of Accounting Program

Professor in the Practice of Accounting

- Neck pain

- All day sitting

“I’m tall (6’4”), so a regular height desk means I have to hunch while I type on my computer. Starting in my Ph.D. program days, I developed pretty bad upper back pain. So I actually use my “standing desk” to raise my computer and keyboard to just the right height for when I’m sitting. It works like a charm. It has completely removed my neck pain!”

Brian Akins

Assistant Professor of Accounting

- Back pain

- All day standing, barefoot with two anti-fatigue mats

“I’m more productive in the afternoon. You can’t fall asleep standing up. I found I was getting a lot more done.”

David De Angelis

Assistant Professor of Finance

- Back pain

- Alternates sitting and standing

“I’ve only been doing it one semester, but I’m moving more and more to standing when I need to think.”

Jefferson Duarte

Associate Professor of Finance and

Gerald D. Hines Associate Professor of Real Estate Finance

- Walking desk, alternates between two desks (walking and sitting) with two computers connected remotely. Speed: 1.1 mph

“I didn’t want to be sitting all the time. At this speed, I can read and write without any problems. It helps a lot with my productivity in the afternoon.”

K. Ramesh

Herbert S. Autrey Professor of Accounting

- Avoid late afternoon lethargy

- Hoping to improve focus

“With just four months of use, can’t be confident in identifying specific positive outcomes, but that won’t stop me! Time seems to fly faster. My productivity has gone up in terms of quantity, but only time will tell about its quality!”

This article originally appeared in the Jones Journal, Spring 2016.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Life Of The Party

What Rubi's Quinceañera can teach the U.S. about Latinos.

By Claudia Kolker

What Rubi's Quinceañera Can Teach The U.S. About Latinos

The look was American Gothic, South of the Border. Flanking a teenager in tiara and leopard-print ball gown, Crescencio Ibarra and wife Anaelda stared fixedly into a camera in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, and invited viewers to their daughter's fifteenth birthday.

More than 1.3 million Facebook users worldwide have since RSVP'd.

The video invitation to Rubi's quinceañera, sometimes called a quince, first surfaced widely last week on YouTube. (Reportedly, Mr. Ibarra hit "public" instead of "private" on Facebook.) In the aftermath, Rubi Ibarra García and her slightly stunned parents have become an unprecedented sensation.

For Mexicans and viewers who know their traditions, Rubi's quince is now an online Vesuvius of memes and absurd video parodies. For U.S. marketers, though, it's something else: a glimpse at what makes the vast, coveted and hard-to-reach Latino market tick.

"It really shows the practical power of cultural literacy," says Utpal Dholakia, a management professor at Rice Business School. "It's why business training needs to give global perspective — and why business schools need diverse students, of all backgrounds, not only Latino. At some point, they're going to be educating each other."

Rubi's video certainly gives plenty to study. As she and her mother (swathed in a salmon-pink poncho that's now a meme of its own) look on stonily, father Crescencio faces the camera from under a cowboy hat to make his offer: At the December 26 party, three bands will perform for the celebration, plus a fourth during the meal. A traditional mass will be said. And, to the amusement of hundreds of thousands of viewers, a "chiva" worth $10,000 pesos will be up for grabs. Depending on the region, this may mean either a live goat, cooked cabrito, or a horse race with a big prize.

Quinces are meant to be blowouts, a young woman's debut in her community. Both in Mexico and parts of the United States, serious quinces eclipse weddings. The quince girl gets a giant pastel hoopskirt; teen ladies- and gentlemen-in-waiting practice dance steps for months; traditions like the Last Doll of childhood, the First High Heel of womanhood, the emotional missive, and first waltz with Daddy ensure torrents of tears.

In the Southwest, it's all so tempting that boys and non-Latinos sometimes get quinces too, with touches such as '40s-style zoot suits, hip-hop deejays, and bouncing low-rider limos.

Even so, the Ibarras hardly meant their invitation to race round the world. They certainly couldn't guess that so many Latinos would count themselves as community. "People are having fun with this because it's such a huge part of the culture to celebrate a 'fifteen' that it's very relatable," says Juan Alanis, former Hispanic corporate communications lead for AT&T, and cofounder of Big Oak Tree Media, a communications firm.

Columnist Gustavo Arellano, author of cult favorite "Ask A Mexican!" column in Orange County Weekly, checks off the video's charms. "There's the stoic looks of the mom and Rubi," he says. "There's the clash of culture, millennial versus traditional. The earnestness of the dad. And the innocence of it all: a breath of fresh air in such a cynical world. The laughter that people have isn't necessarily at the family's expense, but rather a feel-good reminder of the truly important things in Mexican culture: a party, a quince, and a loving family."

Celebrities have invited themselves to the fiesta with tweets, posts and videos. Singer Espinoza Paz was one of several who RSVP'd and asked to perform at the party. Actor Gael Bernal Garcia, famous for the movie Y Tu Mamá También, filmed a parody with a clip-art goat looming on a barn roof and comic Piolín, in a tiara, playing Rubi. (Everyone's invited -- "y tu mamá también," Piolín blurts).

Rubi's family has shown up on Mexican morning shows, and the tweets and RSVPs keep on coming. "Another tortilla please," tweeted one wit, over one face in a shot of thousands of people jammed into a plaza.

"Okay, let's go!" tweeted another, over a Photoshopped image of an elongated bus with roof and sides covered by thousands of clinging riders. Destination: "San Luis Potosí."

Corporations are happily crashing the Rubi trend too. Mexican airline Interjet leapt in with a 30 percent discount on flights to San Luis Potosí. Goat not included, small print advises.

But, as one concerned viewer has queried on Facebook, is it okay for Anglos to laugh?

Absolutely, says Alanis, the media consultant. "It's the kind of story that puts a smile on a lot of people's faces just because of the unexpected attention. It's like the My Big Fat Greek Wedding effect. I think we're kind of saying, 'That's part of me. I know that family. I am that family.'"

Arellanos at first is doubtful the humor can travel, then changes his mind: "Maybe good ol' boys can appreciate it, á là Jeff Foxworthy comedy."

And while not every Mexican girl has or even wants a quince, all know the mystique. That's why Gwendolyn Zepeda, Houston's first poet laureate, who didn't get a quince during her own childhood in Houston, threw herself a raucous do-over decades later: "The Quinceañera You Were Too Poor to Have." Guests thronged, wearing tiaras and tulle, to tell about the quinces they missed — or those that went horribly wrong.

Although Rubi's family didn't plan on entertaining 1.3 million guests, Zepeda says, their expansive hospitality instantly rang true for her. "I went to Mexico often as a teenager, and since my parents didn't want me to going to clubs or bars, I was allowed to go to quinces, even when I didn't know the people," she says. "My dad used to say, it's okay for strangers to show up because a) that means it's a good party, and b) you'll contribute when the old lady comes around with a basket or during a dollar dance with the quince girl."

Rubi's quince took off, in other words, because it's full of precise references: funny at a time when many Mexicans feel pummeled; a mirror on intact, familiar habits; and a rowdy group conversation — not a speech. While all this makes it easy for Mexican consumers, businesses and entertainers to join the party, non-Latinos who take the time can learn the moves too.

"The Disney company could easily have stepped in saying, 'We're going to make this quince a true princess experience,' and then sent in a horse and carriage," Alanis says. "It would have translated perfectly."

This article originally appeared online in Gray Matters.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Intense Interest

Interest rates have outsized effects on final value of a bankrupt company.

Based on research by Antonio Merlo (former professor and dean at Rice University) and Xun Tang

When A Company Goes Bankrupt, Interest Rates Have An Outsized Effect On Final Value

- Corporate bankruptcies, which allow claimants to negotiate over a bankrupt company's value, are often shrouded in mystery until the deal is finally completed.

- Stochastic bargaining models, which consider the randomness of a set of variables over the time of a negotiation, may shed light on the factors that drive both deal timing and valuation.

- New research shows that interest rates have outsized effects compared to stock prices on the final negotiated value of a bankrupt company.

When a company goes bankrupt, its creditors start fighting. Each has a plan for restructuring the struggling company that best benefits their own interests, aiming to find value in the company above its cash liquidation value.

But bankruptcy negotiations are buffeted by random, complicated factors beyond bickering creditors and the clamor of other claimants. Fluctuations in macroeconomic conditions, such as interest rates and other factors, make themselves felt in the form of up-and-down stock prices. Not only that: Information revealed in private talks between the company and its claimants may affect company value—but be unavailable to the public.

It’s a central paradox for both economists and the public: how to figure out the factors behind the outcome of a deal when you can’t see any of the intermediate steps that led to the deal, only its final value.

To better understand the factors driving bankruptcy negotiations, former and current Rice economists Antonio Merlo and Xun Tang, coauthored a study using a stochastic model. (These are models based on the fact that state variables evolve randomly over time). The researchers found that in creditors’ quest to extract as much extra value as possible from a bankruptcy — a prize the researchers called “cake” — what mattered most were fluctuations in interest rates.

To conduct the study, Merlo and Tang used U.S. Corporate Bankruptcy Data from 1990-1997, to select publicly traded companies that reorganized by 2000, and looked at the 77 companies that provided final reorganization values and their distribution between all claimants. The researchers then overlapped data from three-month Treasury bills and industry stock price indices onto the bankruptcies’ time periods — seemingly random events that closely affect negotiations over company value.

The data showed that changes in interest rates tended to have a larger effect on both the probability of claimants reaching an agreement and the agreement itself being larger. Furthermore, interest rates affected “cake” values regardless of the simultaneous effect of stock prices, while the same cannot be said for stock prices regardless of interest rates.

But interest rates also came to matter more as the deals progressed. The more time claimants took to close a deal, and the more that they needed the cash from the bankruptcy, the more likely they were to want a quick settlement that avoided high interest rates in the capital markets. While there is nothing like a bankruptcy to focus a creditor’s mind, rising interest rates seem to heighten their sense of urgency in a way that even stock prices do not.

Antonio Merlo is the former George A. Peterkin Professor and Chair of the Department of Economics at Rice University.

Xun Tang is associate professor of Economics at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Merlo, A. & Tang, X. (2012). Identification and Estimation of Stochastic Bargaining Models. Econometrica, 80(4), 1563-1604.

Never Miss A Story