What Really Drives Data Center Location Decisions in the U.S.?

A new study shows a divided geography: some facilities cluster in cities for speed and access, while others move to rural regions in search of scale and lower costs.

Based on research by Tommy Pan Fang (Rice Business) and Shane Greenstein (Harvard)

Key takeaways:

- Third-party colocation centers are physical facilities in close proximity to firms that use them, while cloud providers operate large data centers from a distance and sell access to virtualized computing resources as on‑demand services over the internet.

- Hospitals and financial firms often require urban third-party centers for low latency and regulatory compliance, while batch processing and many AI workloads can operate more efficiently from lower-cost cloud hubs.

- For policymakers trying to attract data centers, access to reliable power, water and high-capacity internet matter more than tax incentives.

Recent power outages and the surge in AI-driven computing have made data center siting decisions more consequential than ever, especially as energy and water constraints tighten. Communities invest public dollars on the promise of jobs and growth, while firms weigh long-term commitments to land, power and connectivity.

Against that evolving backdrop, a critical question comes into focus: Where do data centers get built — and what actually drives those decisions?

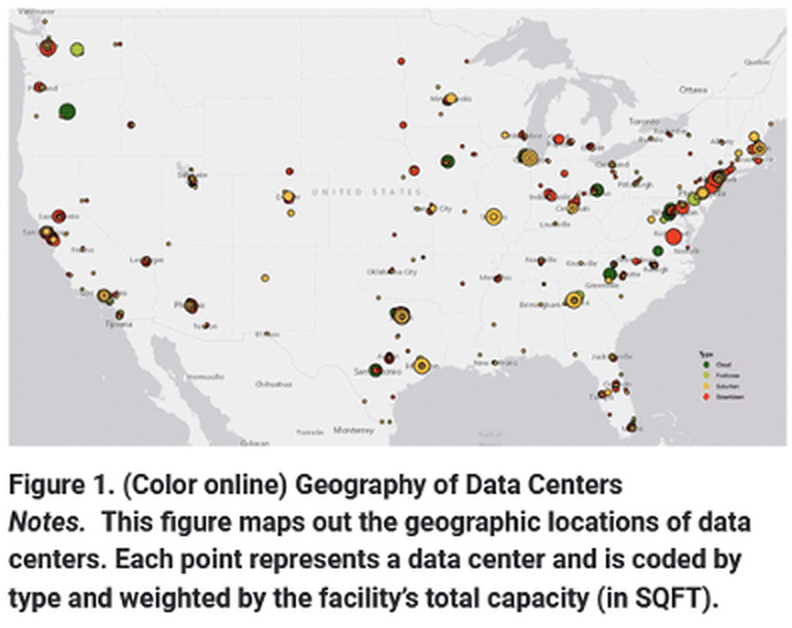

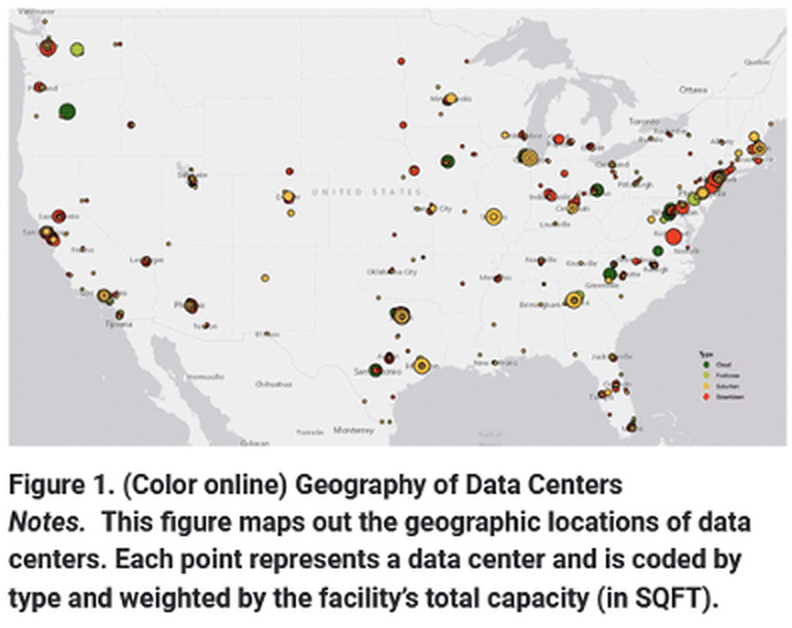

A new study by Tommy Pan Fang (Rice Business) and Shane Greenstein (Harvard Business School) provides the first large-scale statistical analysis of data center location strategies across the United States. It offers policymakers and firms a clearer starting point for understanding how different types of data centers respond to economic and strategic incentives.

Published in the journal Strategy Science, the study examines two major types of infrastructure: third-party colocation centers that lease server space to multiple firms, and hyperscale cloud centers owned by providers like Amazon, Google and Microsoft.

“The cloud feels weightless,” Pan Fang says, “but it rests on real choices about land, power and proximity.”

What are the two main data center location strategies?

The study draws on pre-pandemic data from 2018 and 2019, a period of relative geographic stability in supply and demand. This window gives researchers a clean baseline before remote work, AI demand and new infrastructure pressures began reshaping internet traffic patterns.

The findings show that data centers follow a bifurcated geography:

- Third-party centers cluster in dense urban markets, where buyers prioritize proximity to customers despite higher land and operating costs.

- Cloud providers, by contrast, concentrate massive sites in a small number of lower-density regions, where electricity, land and construction are cheaper and economies of scale are easier to achieve.

Third-party data centers, in other words, follow demand. They locate in urban markets where firms in finance, healthcare and IT value low latency, secure storage, and compliance with regulatory standards.

Using county-level data, the researchers modeled how population density, industry mix and operating costs predict where new centers enter. Every U.S. metro with more than 700,000 residents had at least one third-party provider, while many mid-sized cities had none.

This pattern challenges common assumptions. Third-party facilities are more distributed across urban America than prevailing narratives suggest.

Customer proximity matters because some sectors cannot absorb delay. In critical operations, even slight pauses can have real consequences. For hospital systems, lag can affect performance and risk exposure. And in high-frequency trading, milliseconds can determine whether value is captured or lost in a transaction.

“For industries where speed is everything, being too far from the physical infrastructure can meaningfully affect performance and risk,” Pan Fang says. “Proximity isn’t optional for sectors that can’t absorb delay.”

Why does distance matter for cloud data center costs?

For cloud providers, the picture looks very different. Their decisions follow a logic shaped primarily by cost and scale. Because cloud services can be delivered from afar, firms tend to build enormous sites in low-density regions where power is cheap and land is abundant.

These facilities can draw hundreds of megawatts of electricity and operate with far fewer employees than urban centers. “The cloud can serve almost anywhere,” Pan Fang says, “so location is a question of cost before geography.”

The study finds that cloud infrastructure clusters around network backbones and energy economics, not talent pools. Well-known hubs like Ashburn, Virginia — often called “Data Center Alley” — reflect this logic, having benefited from early network infrastructure that made them natural convergence points for digital traffic.

Local governments often try to lure data centers with tax incentives, betting they will create high-tech jobs. But the study suggests other factors matter more to cloud providers, including construction costs, network connectivity and access to reliable, affordable electricity.

When cloud centers need a local presence, distance can sometimes become a constraint. Providers often address this by working alongside third-party operators. “Third-party centers can complement cloud firms when they need a foothold closer to customers,” Pan Fang says.

That hybrid pattern — massive regional hubs complementing strategic colocation — may define the next phase of data center growth.

Looking ahead, shifts in remote work, climate resilience, energy prices and AI-driven computing may reshape where new facilities go. Some workloads may move closer to users, while others may consolidate into large rural hubs. Emerging data-sovereignty rules could also redirect investment beyond the United States.

“The cloud feels weightless,” Pan Fang says, “but it rests on real choices about land, power and proximity.”

Written by Scott Pett

Pan Fang and Greenstein (2025). “Where the Cloud Rests: The Economic Geography of Data Centers,” Strategy Science.

Never Miss A Story