When Doing Good Comes With Stigma

For social ventures rooted in marginalized communities, sharing their origin story can deter mainstream customers due to fear of stigma transfer.

Based on research by Diana Jue-Rajasingh (Rice Business) and Wesley W. Koo (Johns Hopkins)

Key takeaways:

- Origin stories that highlight roots in marginalized communities carry social risk for consumers outside of those groups, making them wary of buying in.

- Research shows the key reason for this is stigma transfer — the fear that purchasing the product will signal lower status by association.

- However, framing the origin story in a certain way can encourage those same consumers to offer non-purchase support, such as joining a mailing list.

For social-venture founders, new research from Rice Business assistant professor Diana Jue-Rajasingh points to an uncomfortable tension: the origin story that anchors a company’s mission can, in some contexts, slow its growth.

Before earning her doctorate, Jue-Rajasingh co-founded Essmart, a company that distributes socially beneficial products across rural India. As the company expanded to more affluent customers, she faced a dilemma familiar to many mission-driven founders: how prominently to feature its rural roots.

“Do we emphasize our rural origin story as we expand? That was something we had to think about,” Jue-Rajasingh says. “Is it even useful to talk about the good we’re doing in villages when we’re marketing to people who may not care about that?”

To see whether that concern held up more broadly, Jue-Rajasingh partnered with longtime collaborator Wesley Koo of Johns Hopkins University. In a new paper published in the Strategic Management Journal, they examine how sharing a social venture’s origin story affects new customers and how different ways of framing that story shape consumer response.

When Origin Stories Backfire

Their survey-based field experiment confirms the worry. Affluent, urban consumers who heard an origin story tied to a poor, rural community were less likely to purchase the product and more likely to stigmatize its original customer base.

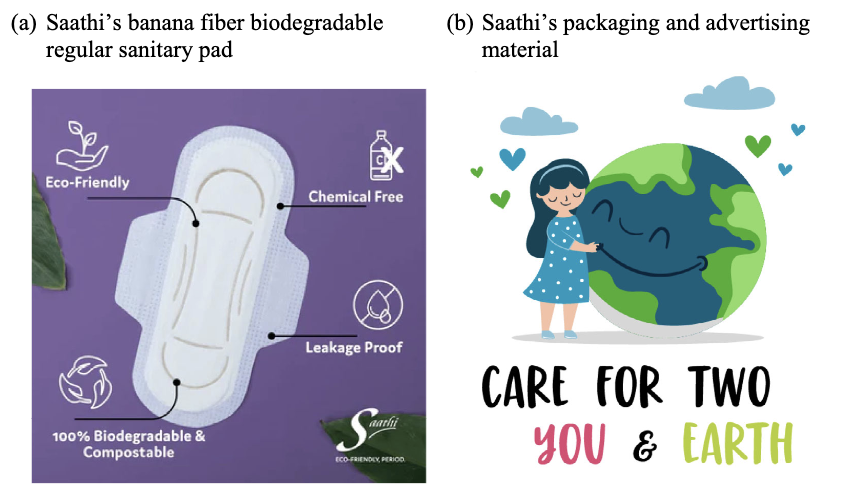

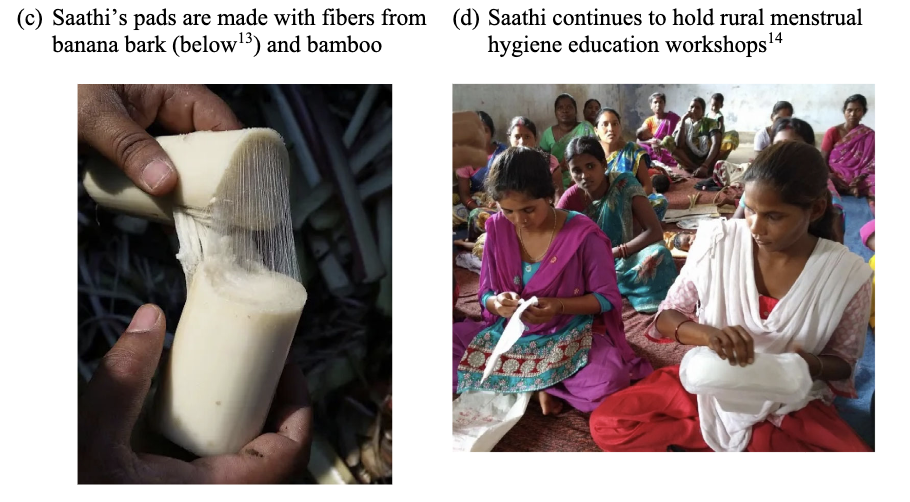

Jue-Rajasingh and Koo centered the study on Saathi Pads, a growing enterprise founded in 2015 to increase access to sanitary pads in rural India. Its early decentralized production model proved financially unsustainable, prompting a shift to centralized manufacturing and a new urban market — raising the question of how, or whether, to foreground Saathi’s social-mission origins.

To test the effects, the researchers recruited 283 female respondents at a university in Delhi and presented four versions of Saathi’s origin story: a basic rural-roots version; a technology version highlighting design choices; a social-impact version; and a combined tech-social version. A control group received no origin story. Participants then evaluated the company, product quality, and their likelihood of purchasing or recommending the pads.

“Part of me wants to say, ‘Own your story.’ But another part of me says, for the sake of ensuring you can grow your company, remember that sometimes you can’t tell the same story to everyone.”

The Role of Stigma Transfer

As it turned out, none of the four framings increased purchase intent compared with the control condition of no origin story at all. Interestingly, however, respondents exposed to the social-impact version were slightly more willing to support the company in non-purchase ways, such as joining a mailing list.

To understand the aversion to these stories, the researchers tested three explanations: misunderstanding of the venture’s social mission, skepticism about motives and stigma transfer. The analysis pointed to this third explanation, stigma transfer, as the primary mechanism. Respondents who grew up in cities, had higher-status parents and reported higher incomes were especially likely to rate Saathi and its products as inferior after hearing the rural origin story.

“At first, the stigma finding surprised me,” Jue-Rajasingh says. But it also echoed her experience as a founder. “When we promoted our organization, we often featured a middle-class person on a poster to inspire lower-income audiences. I noticed organizations never did the reverse.”

The Importance of Strategic Storytelling

Jue-Rajasingh admits she feels conflicted about the implications of her study’s findings for social ventures.

“Part of me wants to say, ‘Own your story.’ But another part of me says, for the sake of ensuring you can grow your company, remember that sometimes you can’t tell the same story to everyone.”

Her findings also point to several areas where more research is needed. This study focused on a specific context — an Indian social enterprise, a women’s health product and an urban university sample — all of which shape how status dynamics show up. Future work could test whether similar stigma-transfer effects appear in different countries, with different types of products or across other consumer groups.

Another open question is whether certain forms of messaging, visual cues or trust-building strategies can reduce or counteract the stigma mechanism rather than simply avoiding it.

Still, Jue-Rajasingh says there are practical takeaways for founders and managers now. For example, audience targeting matters. “As much as you can, try to target your audience,” she says. “For a mainstream audience, emphasize how the origin story can benefit them; maybe that’s a design or technology tie-in. But for the original customers, those who really do care — you can keep telling your social origin story.”

In other words, the story doesn’t need to disappear. But social-venture leaders may need to decide when to center it, when to reframe it and when to let the product speak first.

Written by Katie Gilbert

Jue-Rajasingh and Koo (2025). “From Margins to Mainstream: The Narrative Dilemma in Scaling Social Ventures,” Strategic Management Journal.

Never Miss A Story