Mail-Art Company, Tellinga, Now Offers Non-fungible Token (NFT) Crypto Art as Part of Custom-Created Mailing Experiences - Unique Digital Gifts Backed by Power of the Blockchain

With the recent upsurge in cryptocurrency and digital art popularity, Tellinga announced it has added custom NFT art as part of its personalized story-mailing experiences. The company was founded by Rice MBA '19, Alex Kurkowski.

Expect The Unexpected

Looking Back On Year One At Rice Business

March 5, 2020 — I got a phone call from a Houston-area number. I had been in an anxious headspace all day and struggled to stay focused. As soon as my phone lit up, I jumped in my chair and stepped outside to answer.

“Hi Nathan!” A cheerful voice greeted me. “This is Jessica from the Admissions Office at Rice Business, and I wanted to let you know that you have been admitted to the full-time MBA program for the fall!” The news left me stunned.

“Wow…” is all I could say. Feeling emotional, I leaned against the wall of the stairwell.

The road to starting my MBA was often long and lonely. As a first-generation college student and son of a Filipina immigrant and Navy veteran father, I’d focused my life on achieving, getting an education and advancing my career. But by the time I considered an MBA, I was floundering, unsure if my current field, digital marketing, was where I wanted to stay. An MBA, I thought, would help me challenge myself and pivot.

So when I got the call from Rice Business, I felt I had suddenly lucked into a ticket to re-imagine my life and career. The future never looked brighter.

Then came the rapid transition to “work from home.” New cases of COVID-19 were spreading uncertainty across the country. My visions of Houston MBA life, complete with Thursday night Partios, drinks with classmates and networking events started to fade, as Zoom info sessions started to flood my calendar. My wife, Lauren, and I agonized about upending our lives during a pandemic for what would look like a virtual MBA experience.

Nevertheless, I sent my deposit and confirmed it: I would be attending Rice in the fall.

That first semester was dizzying. Between the workload and the endless string of school-related events, the year felt like a decade. Now, with two terms completed, and with my last term of core classes almost done, I’d like to share some of the lessons I learned from starting an MBA in the middle of a pandemic.

1. It’s time to change our assumptions of being in control.

Once I started business school, I used to tell myself, the path to follow will be clear. I was flat out wrong.

I was overwhelmed by the flood of information, the case studies, the problem sets and struggling to keep up. Many days, I wondered if I’d made a mistake. The difficulty of school mixed with the accomplishments and performance of my peers left me with a deep sense of impostor syndrome. And even with hybrid classes, the severe diminishing of social activity left me feeling isolated and longing for old friends.

To my surprise, though, in the midst of all this uncertainty came new opportunities. I signed up for a program that gave me access to a mentor. Rice Business connected me with a leadership coach. I competed in the first-ever racial justice case competition. And as the months passed, I found numerous other ways to connect and get involved that I’m not sure I would have under “normal” circumstances.

I’d started out assuming I could control what was in front of me, but circumstances forced me to adapt. The truth is that while most of us like to think we’re in control that was never a trustworthy assumption — even before 2020. For those of us who like to control things, the pandemic year was a crash course in accepting that we will never be in full control.

2. Get comfortable with ambiguity.

Preparing to attend school virtually, I didn’t know what life in Houston was like aside from what other friends shared with me. There was no assurance of what the market would look like for internships, or even what the classroom experience would be like. I had only my current situation — and my opportunity to study at Rice.

That’s not unlike business, I discovered. In case studies for business school, you only have the narrative, the decision at hand, and a series of exhibits of charts and financial statements, leaving you to untangle the knots and start making sense of what’s in front of you. Sometimes the information isn’t perfect, and you’re always wanting more information or wishing you had one specific piece.

Here’s the kicker: you’re not going to get that information. And you still have to make a decision. The “risk” is never zero.

As I’ve gotten involved with the entrepreneurship and innovation space here at Rice and in Houston, I’ve grown to appreciate the mindset of getting familiar with problem spaces, testing assumptions and gathering insights to the best of my ability.

3. The most important decision is the next one.

The pandemic has definitely altered everyone’s immediate plans. But it’s also reprogrammed my own tendency to be consumed with the long-term future. I know that I have deliverables due next week, a conference to attend to tomorrow. When I get home from studying on campus, I have some catching up to do with my wife as we walk our dog. Whatever happens day by day, I realized, I can only say yes or no, do or do not, and then see where my next decision leads. It’s a hard lesson learned for a somewhat Type-A person.

Now I’m working on one thing at a time, maintaining my focus, keeping my standards high — and taking that next step. But when I look back, I can already see how far I have come. I can’t wait to see the decisions that lie ahead of me — and where my choices will lead me next.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Medium.

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Rice Business Plan Competition events to be livestreamed

Three events during this week’s Rice Business Plan Competition (RBPC) — the world’s largest and richest student startup competition — will be livestreamed.

Three events during this week’s Rice Business Plan Competition (RBPC) — the world’s largest and richest student startup competition — will be livestreamed.

Hosted by the Rice Alliance for Technology and Entrepreneurship and Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business, the RBPC will gather teams from 54 universities and six countries to compete for more than $1.2 million in prizes and investments. The elevator pitch competition on Tuesday, April 6, and the live final round and awards presentation on Friday, April 9, will be broadcast on YouTube and the RBPC website.

What: 2021 Rice Business Plan Competition elevator pitch competition, live final round and awards presentation.

When (all times CDT):

- Elevator pitch competition: Tuesday, April 6, 4-5:15 p.m.

- Live final round: Friday, April 9, 9 a.m.-noon

- Awards presentation: Friday, April 9, 1:30-2:15 p.m.

Where: Watch the livestreams on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/ricealliance or at https://rbpc.rice.edu/2021-competition.

The student startups will compete in five sector categories: energy, clean tech and sustainability; life sciences and health care solutions; consumer products and services; hard tech; and digital and enterprise software.

The awards presentation will also include short updates from last year’s grand prize winner, Aurign, the second-place team, Nanopath, and the first RBPC startup to go public, Hyliion.

Past competitors have raised more than $3.1 billion in total capital, and 257 startups have gone on to be successful, including 36 acquisitions and two initial public offerings: Hyliion (2015 RBPC finalist) and Owlet Baby Care (2013 RBPC finalist).

For more information about the 2021 Rice Business Plan Competition, visit http://rbpc.rice.edu.

You May Also Like

Rice University’s Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business today announced the launch of its Graduate Certificate in Healthcare Management program, a 10-month, credit-bearing professional credential designed for current and aspiring leaders seeking deep expertise in the business of healthcare.

Tech Companies That Won the Pandemic Are Snapping Up M.B.A.s

After seeing business boom over the past year, Amazon, Zoom and others are swooping in with job offers for business-school graduates as traditional M.B.A. hirers pull back.

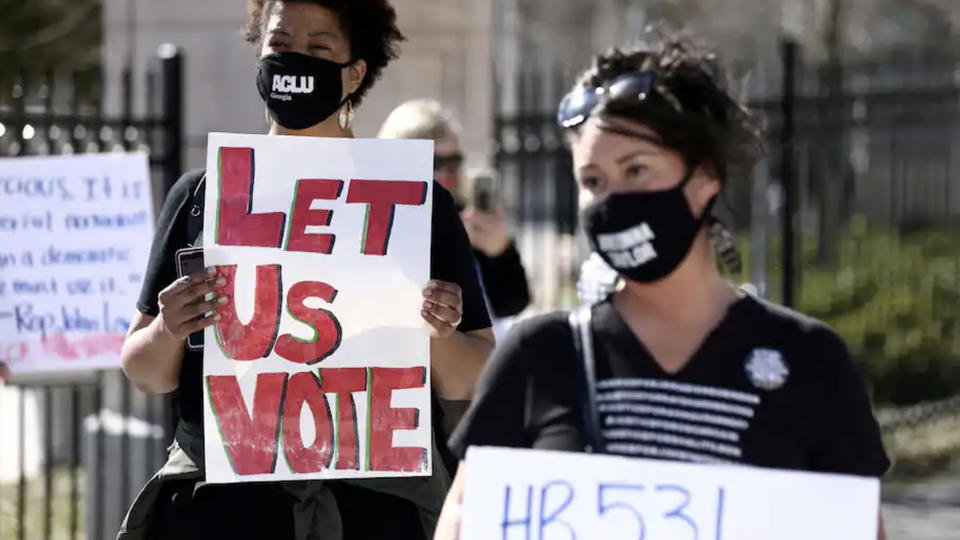

Companies, facing new expectations, struggle with pressure to take stand on Georgia voting bill

Firms are being put on the spot to respond to social and political debates, which presents the risk of making missteps. “A lot of companies follow the leader. They don’t want to stick out,” said Doug Schuler, professor of business and public policy at Rice Business.

‘There is no middle ground:’ Corporate America feels the pressure on voting rights

Remember when you were applying to business school? We know the application process can be an arduous one, and we want to find ways to improve it. Doug Schuler, professor of business and public policy at Rice Business, is quoted.

A Clean Energy Exec Contributing to Corporate Innovation feat. Scott Gale ’19

Season 1, Episode 18

Scott Gale ’19 joins host Christine Dobbyn to discuss how entrepreneurship is becoming a key part of a successful company and the future of Houston as the energy capital of the world.

Owl Have You Know

Season 1, Episode 18

Scott Gale ’19 joins host Christine Dobbyn to discuss how entrepreneurship is becoming a key part of a successful company and the future of Houston as the energy capital of the world.

Subscribe to Owl Have You Know on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Youtube or wherever you find your favorite podcasts.

You May Also Like

28 Fully Funded Ph.D. Programs

Students interested in graduate research in various fields, from public health and English to computer science and engineering, have numerous options for Ph.D. programs that offer full funding. These programs typically provide waived tuition and fees, as well as an annual stipend.

Serving size, satisfaction influence food waste on campus

Understanding what drives food choices can help high-volume food service operations like universities reduce waste, according to a new study conducted by a team of experts led by Eleanor Putnam-Farr, assistant marketing professor at Rice Business.

Understanding what drives food choices can help high-volume food service operations like universities reduce waste, according to a new study.

Researchers have concluded that food waste in places like university cafeterias is driven by how much people put on their plates, how familiar they are with what’s on the menu and how much they like – or don’t like – what they’re served.

Food waste has been studied often in households, but not so often in institutional settings like university dining commons. What drives food choices in these “all-you-care-to-eat” facilities is different because diners don’t perceive personal financial penalty if they leave food on their plates.

Published in the journal Foods, “Food Choice and Waste in University Dining Commons — A Menus of Change University Research Collaborative Study” was conducted by a team of experts from Rice University; the University of California, Davis; Stanford University; Lebanon Valley College; the University of California, Santa Barbara; and the University of California, Berkeley. Eleanor Putnam-Farr, assistant marketing professor at the Jones Graduate School of Business, led the effort at Rice.

The researchers conducted student surveys during the 2019 spring and fall semesters to study foods types, diner confidence and diner satisfaction. They used photos taken by diners themselves before and after eating to measure how much food was taken and how much of it went to waste. “Diners were intercepted at their dining halls and asked if they wanted to participate in a study about food choices and satisfaction, but the objective of investigating food waste behavior was not disclosed,” the authors wrote.

The study found the amount of food wasted didn’t significantly differ among types of food. Instead, researchers discovered waste was related to the amount of food diners put on their plates, how satisfied they were with their meals and how often they went to the dining commons. If students were satisfied with their food, they tended waste less of it. And diners who visited the commons most often — making them more familiar with the menus and more confident in their choices — tended to waste less.

Mixed dishes, like sandwiches or stir-fry, took up a greater percentage of the surface area on surveyed plates than animal proteins or grains and starches. Those three types of food took up a greater area of the plates than fruits, vegetables or plant proteins. The amount of food wasted, however, did not significantly differ among the various food categories.

The mixed dishes and animal proteins that took up greater portions of the plate tended to be pre-plated by the commons staff or have a suggested serving size. The study’s results showed that greater amounts of food taken by diners correlated with the item being pre-plated or served by others.

The authors recommend future research on the topic uses their multicampus approach — which enabled them to study food choice among a large and diverse group — to better understand what causes food waste and find out if it can be reduced by interventions such as posting signs that encourage healthier choices.

You May Also Like

Rice University’s Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business today announced the launch of its Graduate Certificate in Healthcare Management program, a 10-month, credit-bearing professional credential designed for current and aspiring leaders seeking deep expertise in the business of healthcare.

Kumon or Montessori? It may depend on your politics, according to new study of 8,500 parents

Whether parents prefer a conformance-oriented or independence-oriented supplemental education program for their children depends on political ideology, according to a research team including Vikas Mittal, professor of marketing at Rice Business.

Whether parents prefer a conformance-oriented or independence-oriented supplemental education program for their children depends on political ideology, according to a study of more than 8,500 American parents by a research team from Rice University and the University of Texas at San Antonio.

“Conservative parents have a higher need for structure, which drives their preference for conformance-oriented programs,” said study co-author Vikas Mittal, a professor of marketing at Rice’s Jones Graduate School of Business. “Many parents are surprised to learn that their political identity can affect the educational choices they make for their children.”

Supplemental education programs include private tutoring, test preparation support and educational books and materials as well as online educational support services. The global market for private tutoring services is forecasted to reach $260.7 billion by 2024, and the U.S. market for tutoring is reported to be more than $8.9 billion a year. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are more than 100,000 businesses in the private education services industry. Supplemental education program brands are among the top 500 franchises in Entrepreneur magazine’s 2020 rankings, and they include popular providers such as Kumon (ranked No. 12), Mathnasium (No. 29) and Huntington Learning Center (No. 39).

For over five decades, education psychologists have utilized two pedagogical orientations — conformance orientation and independence orientation. A conformance orientation is more standardized and guided, emphasizing lecture-based content delivery, knowledge and memorization, frequent use of homework assignments, standardized examinations with relative evaluation and classroom attendance discipline and rules. In contrast, an independence orientation features discussion-based seminars and student-led presentations, an emphasis on ideas rather than facts, use of multimodal interaction instead of books, and highly variable and unstructured class routines. The two approaches do not differ in terms of topics covered in the curriculum or the specific qualities to be imparted to students.

The research team asked parents about their preferences for different programs framed as conformance- or independence-oriented. In five studies of more than 8,500 parents, conservative parents preferred education programs that were framed as conformance-oriented, while liberal parents preferred independence-oriented education programs. This differential preference emerged for different measures of parents’ political identity: their party affiliation, self-reported political leaning and whether they watch Fox or CNN/MSNBC for news.

“By understanding the underlying motivations behind parents’ preferences, educational programs’ appeal to parents can be substantially enhanced,” Mittal said.

"Supplemental tutoring will be a major expenditure and investment for parents grappling with their child’s academic performance in the post-pandemic era. Informal conversations show parents gearing up to supplement school-based education with tutoring. Despite this, very little research exists about the factors that affect parents’ preference for and utilization of supplemental education.”

Mittal cautioned that these results do not speak to ultimate student performance. “This study only speaks to parents’ preferences but does not study ultimate student achievement,” he said.

The paper, “Political Identity and Preference for Supplemental Educational Programs,” which is forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing Research, was co-authored by professor Jihye Jung of UTSA. It can be downloaded at https://doi.org/10.1177/00222437211004252.

You May Also Like

Rice University’s Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business today announced the launch of its Graduate Certificate in Healthcare Management program, a 10-month, credit-bearing professional credential designed for current and aspiring leaders seeking deep expertise in the business of healthcare.