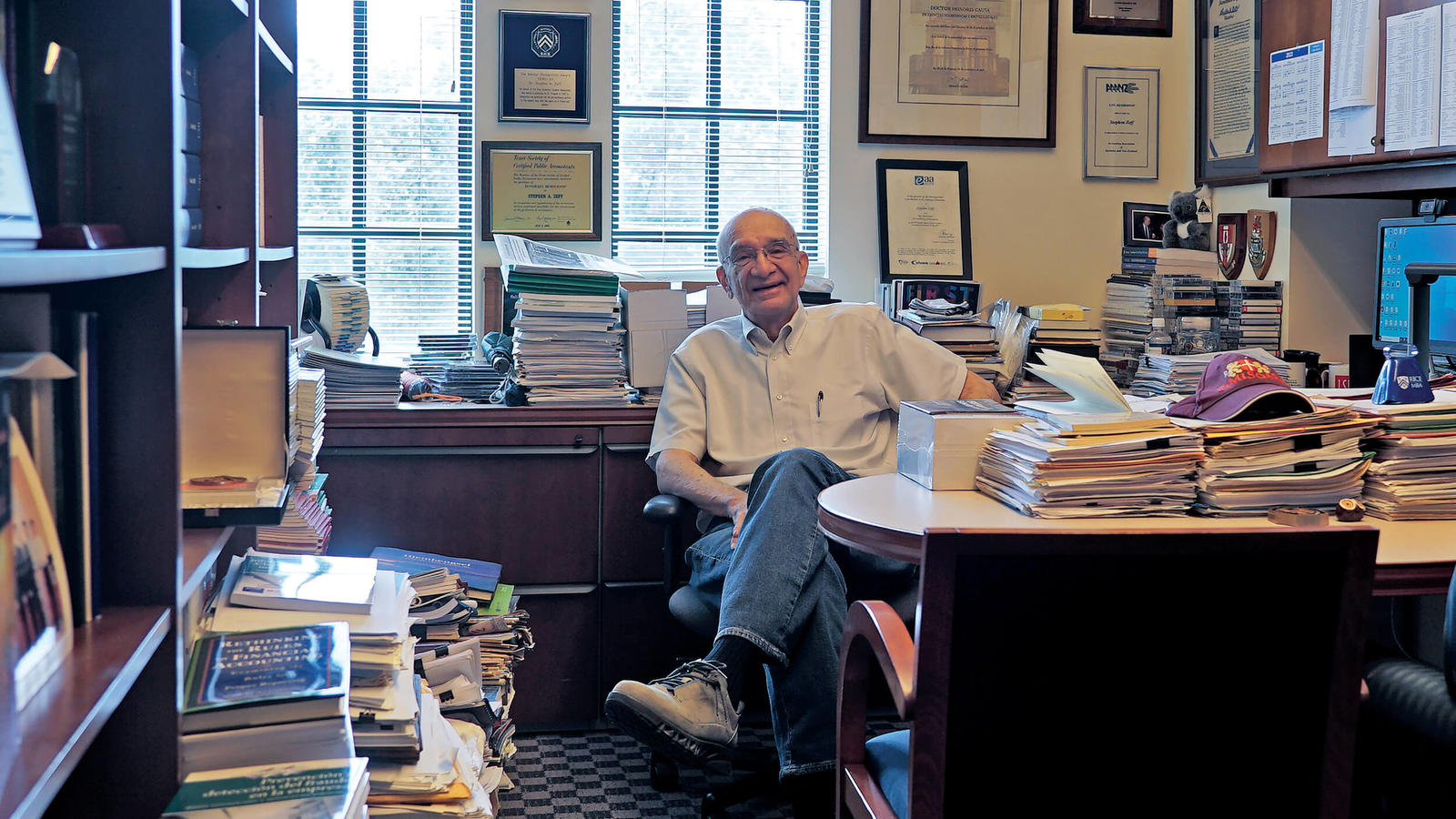

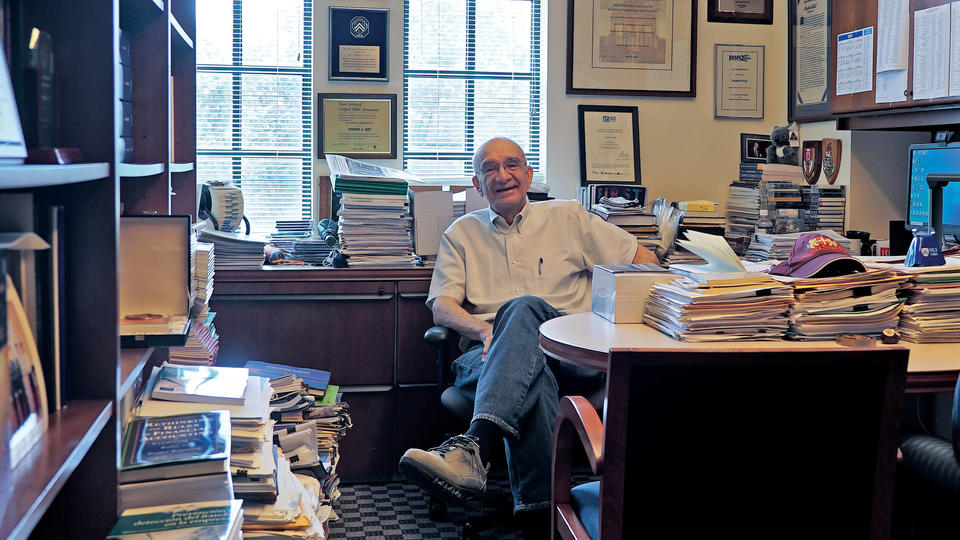

Step Into Stephen Zeff's Office

Renowned accounting professor Stephen Zeff recently celebrated his 90th birthday, but he isn’t slowing down.

Where there’s room for both wisdom and whimsy

Renowned accounting professor Stephen Zeff recently celebrated his 90th birthday, but he isn’t slowing down. Earlier this year, he gave two major international lectures in Finland and England. His youthful energy comes from teaching, he says. “If you stop moving, learning and growing, your students are going to leave you behind.”

Zeff’s office is a tight but magical space, especially if you love books and enjoy talking about history and travel. His walls are lined with texts, awards and personal effects, and his space includes not just one – but two – overflow areas in McNair Hall that house his one-of-a-kind collection of accounting materials dating to the early 1900s.

We recently spoke with Zeff about some of the objects in his office that mean the most to him:

- A custom-made bobblehead doll resembles the professor. His department colleagues gifted it to him in 2011 during a dinner in Denver to commemorate his 50th year as an academic. The dinner was attended by more than 50 accounting faculty colleagues from around the world, at the time of the annual meeting of the American Accounting Association.

- A crystal clock sits on the shelf where he keeps the books he’s written or edited — a total of 32 during his storied career — from biographies of pioneer accountants to histories of accounting as a discipline.

- Zeff’s three honorary doctorates line the wall behind his desk — from universities in Canada, Finland and Spain. An avid internationalist, Zeff has given countless lectures (including in Spanish!) and held numerous visiting appointments around the world.

- A small black-and-white photo of his family was taken in the 1940s. The photograph signifies the things that matter most to Zeff: family, history, travel and connecting with people.

Among fellow accounting historians, Zeff has a reputation as someone who treasures old books. It’s a reputation he enjoys. His two overflow spaces are tucked away in the Business Information Center (BIC), and his archive is likely the only of its kind. Many of the books and journals here have not been digitized and constitute the only remaining copies. Zeff’s textual rescues have proven essential to dozens of researchers in the field.

Here’s to many more years!

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Texas’ unemployment rate is among the nation’s worst — but experts say it signals a growing economy

The state has yet to return to its pre-pandemic unemployment rate of about 3.5%, even as it leads the country in new jobs created. Rice Business dean Peter Rodriguez weighs in: “You can see the unemployment rate go down, but it will go down because of frustrated workers exiting the labor force and even exiting the state.”

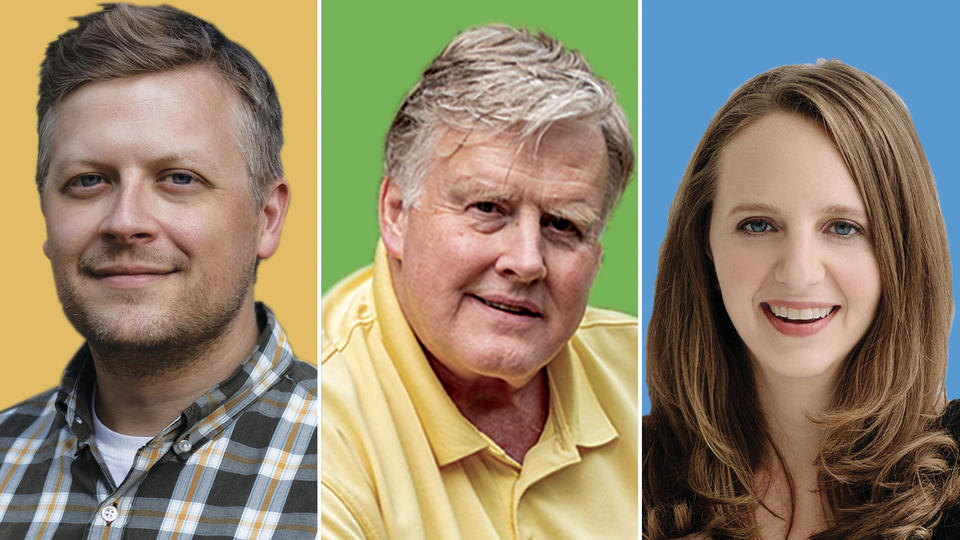

Houston Innovation Awards names prestigious panel of judges for 2023 awards

Ten Houstonians are in the hot seat for deciding the best companies and individuals in Houston's innovation ecosystem, including Aziz Gilani, adjunct professor of entrepreneurship at Rice Business.

Impressions

Students representing all nine of our programs

As a new school year begins,

current students — one from each of our nine degree programs, including the first cohort from our Hybrid MBA — answer questions about their time at Rice Business, what they hope for after graduation and their favorite books.

PMBA-W Chido Osueke ’24

Plans post-graduation?

I will continue to work with industry leaders focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the utility industry through carbon capture technologies, renewable power generation and the reduction of sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). I plan to execute business and engineering solutions that deliver tangible benefits to the global community throughout the value chain.

MBA@Rice Elizabeth Garrett ’24

What do you hope to take away from your time at Rice Business?

My time at Rice has already given me the ability to see business challenges through perspectives I just didn’t have access to before. Additionally, I’ve made strong connections with some incredibly bright and interesting people. They open my mind and give me energy that I know will continue to fuel me as I carry on with my journey.

Undergrad Business Major Daniel Ling ’24

Plans post-graduation?

I’ll be joining Bain full time as an associate consultant in the Houston office! But before that, I plan to take some time off and travel — China, Argentina and Europe top of list — as well as work on scaling my e-commerce business.

PMBA-E Nikki Suarez ’24

What do you hope to take away from your time at Rice Business?

As a Hispanic woman, I view my experience here as a pivotal step to breaking through the glass ceiling and leveraging my unique perspective and skills honed during this MBA program to earn a seat at decision-making tables.

FTMBA Isha Vaishampayan ’24

Plans post-graduation?

I would love to secure and build my career in the technology industry. Also, I want to travel the world to explore, immerse myself in new experiences and gain new perspectives. And finally, I would love to volunteer to serve my community and engage in meaningful work for underrepresented communities.

Hybrid MBA Alexis Smith ’25

Plans post-graduation?

My goal is to advance within my current company, Next Level Medical. I’d like to attain a C-suite leadership position, through which I can continue positively impacting team members’ lives while furthering our mission of delivering high-quality, affordable healthcare.

MAcc Ethan Powell ’24

Favorite book?

“The Giving Tree ” by Shel Silverstein. My parents read this book to me all the time when I was growing up, and then gave me a copy as a high school graduation gift so I would always remember to serve others and to never take people for granted when they make sacrifices for me.

Ph.D. Baifu Chen

Favorite book?

“The Three-Body Problem” by Cixin Liu. I like to quote George R. R. Martin’s comments on this book as “a unique blend of scientific and philosophical speculation, politics and history, conspiracy theory and cosmology.”

EMBA IJ Onianwa ’24

Favorite book?

“Dare to Lead” by Brené Brown. Her take on leadership resonates with me. To me, it is more than just a leadership book. The insights in her book can be applied to any relationship situation.

Keep Exploring

Major Transition

There is no doubt that the energy transition will happen, but we’re all still figuring out how to navigate it.

There is no doubt that the energy transition will happen, but we’re all still figuring out how to navigate it. Nicola Secomandi, the Houston Endowment Professor of Management – Operations Management, is engaged in related research and teaching to help businesses prepare.

Governments and businesses will make crucial decisions about the energy transition in the coming decades — and many of those decisions will hinge on research and current best practices. In July, Nicola Secomandi assumed a new role at Rice Business: senior advisor to the dean on energy transition.

In this role, Secomandi will conduct new research on the energy transition process and will teach rigorous, practical and relevant topics related to the transition. He will also join others at Rice Business, including Linda Capuano, professor in the practice of energy management and advisor to the dean on energy initiatives, in participating in — and adding to — the global conversation and thought leadership on the energy transition.

Here, Secomandi, who came to Rice Business from Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business a year ago, discusses his new role, how he hopes to make an impact at Rice Business and beyond, and the complicated challenges ahead.

Since Rice Business is located in the energy capital of the world, do you agree that we are in a unique position to examine and influence the ways companies are making decisions around the transition?

Indeed, energy and Houston go hand in hand. Organizations and companies in the Houston area are actively engaged in the energy transition. Oil and gas firms have long been key constituencies in our state. They are currently engaged in investigating low carbon solutions — for instance, supplementing their operations with carbon capture, use and storage. As another example, local stakeholders have identified the Houston area as an ideal candidate for a global clean hydrogen hub.

I am fortunate to be involved with our MBA program’s energy and operations curricula, for which I’ve developed and delivered an elective course on managing energy assets. Because several of our MBA students work in, or will join, energy companies, this course is a two-way dialogue. I can learn from students about pressing business challenges that energy companies face. Students can learn how to address, in a structured way, both ongoing and future business issues. There is always a useful tension between addressing current challenges and preparing to solve future problems. My course is designed to help facilitate that kind of critical thinking.

In addition, events this year will focus on the energy transition. The Rice Alliance for Technology and Entrepreneurship organizes the Energy Tech Venture Forum, which brings together energy venture capitalists, investors and entrepreneurs. This year its attention will be on technologies and initiatives central to the energy transition. The Rice Energy Finance Summit will also showcase the energy transition. Rice Cleantech Innovation Competition, a student contest, will as well. Participating in these events is a useful way to learn about the latest innovations that are taking place — or will take place — in industry.

Talk to us about your work at Carnegie Mellon. How will that work in energy influence your work at Rice Business?

Most of my energy-related work so far has been on energy storage — mainly natural gas in underground caverns, but also liquefied natural gas at regasification terminals and electricity in batteries, both stand-alone and in conjunction with wind energy generation. Further, I have worked on natural gas production and transportation, including technology adoption and deployment, and more recently on biorefineries.

Carnegie Mellon has a culture of engaging in research focused on important real-world problems; that is, the school takes a problem-solving approach. For example, my energy work is grounded on the operations of merchant energy trading companies, a business that I learned by working directly in the field after my Ph.D. The same problem-solving approach will continue to shape my work at Rice Business.

Everyone discusses the energy transition, but the issues are complex and ever evolving. Most people don’t know a whole lot about the best ways to move forward. Where do we start?

The end goal is clear: To decarbonize our society on a global scale. What is unclear are the specific paths different companies and governments will take to get there. The obvious starting point for me is learning what organizations are doing currently. The transition to a world in which energy will be predominantly clean will take decades, so it’s important that we engage in this process now.

During the pandemic, you spent a great deal of time learning all you could about the ways companies and organizations are approaching the energy transition. In fact, you’ve written a paper on what you found. What can you tell us about the current practices out there?

Yes, I spent a substantial amount of time reading reports by consulting companies and government agencies. I also read about projects that firms are carrying out or are thinking about starting. This activity has given me a broad view on the status quo.

Consulting firms and government agencies are actively engaged in formulating global decarbonization strategies. These strategies are developed with particular assumptions about climate change goals. For instance, they analyze how the balance between fossil fuels and renewable energy sources must shift over time to align with a target rise in temperature. These projections offer companies concrete examples of what needs to happen to achieve these goals.

The challenge for energy and other companies is to decide what to do going forward in terms of actual projects for specific assets. In energy production, there is substantial interest and substantial activity related to carbon capture, use and storage; sustainable fuels; wind and solar; flexible power-generation assets; batteries; long-duration energy storage; and hydrogen.

Bringing all these projects to fruition will require managing massive investments, adopting known and emerging technologies, as well as developing new ones. Two key aspects of the clean energy transition are: one, integrating assets that use current and novel technologies; and two, adapting existing assets to incorporate new technologies. The change from old to new energy systems cannot happen instantaneously. Thus, the world cannot go from 80% fossil fuels to 80%-plus clean energy in a single year. So, existing and new assets or technologies will coexist for some time. Further, reusing old facilities when adopting new technologies can be useful (e.g., repurposing oil refineries into biorefineries).

From your research, are there companies that seem to be at the forefront of the thinking behind the transition? What are they doing that puts them ahead?

Energy and other companies are actively driving the transition. It is common for businesses to rely on valuable insights and expertise offered by consulting companies, but some benefit from collaborations with academics. Every company is grappling with the future of energy. But those who lead are operating with a more sophisticated level of decision making based on data and structured analysis, possibly based on collaborations with academics.

La Poste, the French postal operator, is an early example of practice and academic collaboration driving energy transition business decisions. In 2010, this company conducted a study to decide the mix of diesel and electric trucks in its future fleet. At a high level, this approach entailed determining and comparing the projected total cost of ownership (TCO) of using each of two types of technologies: the then-current non-environmentally friendly technology — diesel trucks — and the then-emerging environmentally friendly one — electric trucks. The analysis showed that the TCO for the non-environmentally friendly technology was initially lower than the TCO for the clean one, but it was forecast to increase, whereas the other one was forecast to decrease. The company should have abandoned the old technology and adopted the new one when the two TCOs were projected to cross. In this application, there was very little uncertainty about when this crossing was expected to occur. Research helped the company determine in 2010 that it should have started replacing expiring leases for diesel trucks with new leases for electric trucks in early 2015, which is what La Poste did.

An analogous approach has relevance to making various energy transition decisions. Specifically, some assets that employ non-environmentally friendly technologies may currently be cheaper to operate than assets that are configured to use clean or cleaner technologies. However, the cost of running the former assets will increase due to their negative environmental impact, whereas the cost of running the latter ones will decrease because of both efficiency gains associated with learning curves and their lack of, or reduced, environmental impact. From a business perspective, the best time to embrace the new technology is when these costs are expected to cross. Many factors can affect this time, including government interventions, access to capital, and technical risk. Structured analysis based on data can support this type of decision making.

As a researcher, your work will influence other scholars, as well as students. What is the process of bringing new knowledge into the academic environment and the classroom?

Bringing new knowledge into the academic environment requires innovative ideas and dedication. Taking this knowledge into the classroom entails selecting relevant concepts and communicating them to students in an engaging way. Business research and teaching are connected via practice because known research results can be taught to students, who can then apply them to address current or future business issues. For example, the La Poste approach and its application is a key topic of my MBA course on managing energy assets. New challenges in the field and discussions with students in the classroom — or after they have taken a course — provide ideas for new research, which eventually makes its way into teaching. My MBA course on managing energy assets shares these features. Discussions with students in the classroom — or after they have taken a course — can also spearhead new research. Sometimes teaching activities themselves can lead to new research.

I’m eager to work on new research on the energy transition and bring it into my managing energy assets course to complement existing content. Becoming more involved with industrial projects would help me sharpen my research by refining my thinking in the context of specific settings or giving me access to data. Vincent Kaminski, professor in the practice of energy at Rice Business, and I have been discussing with the editors of a leading operations management journal the possibility of having an energy consulting company give a seminar on the energy transition to connect researchers and practitioners. The idea is to raise awareness among scholars, especially those in the early stages of their careers, about the real-world challenges associated with this topic. The goal is to inspire them to engage in research that has practical relevance. In addition, during the current academic year, we’ll be admitting the inaugural class of the newly created Ph.D. in operations management. It would be great to be able to attract students interested in the energy transition and do joint research with them in this area. ◆

Keep Exploring

From the Dean

“We have achieved an ascent in rankings, with a recent nod from Bloomberg Businessweek, which named us No. 19. This announcement comes on the heels of another top 20 U.S. ranking (No. 17) from the Financial Times, both of which named us the No. 1 business school in Texas.”

A letter from Peter Rodriguez, Dean of the Jones Graduate School of Business

We have achieved an ascent in rankings, with a recent nod from Bloomberg Businessweek, which named us No. 19. This announcement comes on the heels of another top 20 U.S. ranking (No. 17) from the Financial Times, both of which named us the No. 1 business school in Texas.

Looking forward to my eighth year as dean, I’ve been reflecting on all we have accomplished together. In that time, we have launched innovative new programs and leading-edge new courses. We have substantially grown our faculty so that we can conduct groundbreaking research and still deliver more service to our community. And we have achieved an ascent in rankings, with a recent nod from Bloomberg Businessweek, which named us No. 19 for our full-time MBA program. This announcement comes on the heels of another top 20 U.S. ranking (No. 17) from the Financial Times, both of which named us the No. 1 business school in Texas.

Your contributions as an alum, a student, or a member of the faculty or staff shows how much you care about the future of Rice Business. Thank you for all you do.

When I came to Rice, the school was tasked with delivering the university’s first online graduate degree program. This July, MBA@Rice celebrated five years in action. Five years of reaching and educating students living near to campus and across the state and nation. The program is flourishing, ranked No. 12 for online programs by U.S. News and No. 4 for online programs by Princeton Review and Poets & Quants. It is recognized for its rigor and service to students and has become the fastest growing program at the school since its launch. This July also marked the start of our Hybrid MBA — an MBA that combines online and in-person instruction with one weekend a month on campus.

Although some MBAs study in online environments, McNair Hall is teeming with students. Our undergraduate business majors — currently the most popular major at the university — are joining us in classrooms, study spaces, faculty offices and Audrey’s. As Rice Business continues to grow, so will our physical space with a substantial addition to McNair Hall scheduled to begin construction in 2024. I will share updates on this project as it moves forward.

It’s always exciting to begin a new academic year. Nothing inspires me as much as seeing our new students pursue their dreams and work together to change the world. As always, I look forward to aiding and enjoying their continued success.

— Peter

Keep Exploring

Of Prophets and Profits

As houses of worship close across the country, we need a new model for the buildings’ futures.

As houses of worship close across the country, we need a new model for the buildings’ futures — one that can benefit the communities these buildings call home.

Houses of worship in the United States are emptying out, from denomination to denomination, from coast to coast. What we do about them will shape not only our faith institutions, but also our communities for decades to come. We may be looking at the closing of up to 100,000 of the estimated 400,000 houses of worship in the United States. Canada and Western Europe face the same challenge. This decline presents a dilemma for our houses of worship, as well as our towns and cities. After a first career in urban revitalization and a second career in the faith community, I find myself on the front lines of this critical challenge: How can we rethink these spaces to serve the needs of religious organizations and their communities — sometimes in ways neither ever imagined?

But first: why are houses of worship closing? While good data on the topic is hard to come by and numbers can vary among denominations and regions, a Gallup poll shows that Americans are losing interest in organized religion. For the first time in U.S. history, fewer than half of Americans consider themselves members of houses of worship. There are other issues, too. Real estate costs are escalating. Houses of worship no longer need to be neighborhood based; people can connect via the internet to religious services anywhere in the world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged churchgoers to stay home and view online. And, much like in the retail and financial services sectors, churches have migrated toward the mega-, the online and, at the other end of the spectrum, small but customized offerings.

This perfect storm has produced a profound mismatch between sparse congregations and cavernous properties. Congregations cannot afford their real estate, whose neglected roofs, HVAC systems and grounds often lead to further disinvestment.

Religious leaders across most religions and denominations are befuddled by the great emptying. They are educated to spread the Good Word, not act as the Grim Reaper. City planners, burdened by outdated zoning ordinances, building codes and historic preservation ordinances, are equally unprepared.

On the other hand, developers and designers, always eager for a good real estate challenge, see opportunity. The problem here is that they focus more on profitability than community needs or environmental, social and governance factors.

In cities like New York, San Francisco and Houston, real estate developers chomp at the bit to acquire emptying houses of worship and redevelop them into luxury residences. First United Methodist Church in downtown Miami sold to a developer for $55 million. Even if that is a smart move to make a massive profit in large cities teeming with tourism and business, luxury isn’t a solution in the heartland and smaller cities. Closed houses of worship can remain empty for years or decades. According to its planning director, Gary, Indiana, population 68,000, suffers from more than 250 empty churches.

The “for sale” signs that dot the landscape aren’t just a metaphor for the loss of religious services or a beacon for development. My colleagues at Partners for Sacred Places, a not-for-profit organization in Philadelphia, measured the “economic halo effect” of churches that host food pantries, child care centers, self-help groups and the like. They discovered that the average urban historic church contributes to the community more than $140,000 annually in goods and services and delivers an annual economic impact of $1.7 million.

It’s a complex problem, and the ways we address it will impact communities for decades to come.

Footsteps in the Sand

While at Rice Business in the early 1980s, I never dreamed I’d end up using my business education to project the future of houses of worship. Fresh from sleepy upstate New York, with three years as a journalist covering murder and political corruption trials, I was encouraged by Rice to venture into the go-go Houston community. Energy stocks were soaring. The movie “Urban Cowboy,” starring John Travolta, had just been released. The eyes of America were on Houston. My Rice Business internship inspired me to get a post-diploma job at West Houston Association, a not-for-profit, real estate organization in what is now Houston’s Energy Corridor. That, in turn, grew into a career path leading corporate CEO-driven, city center revitalization organizations in Richmond, Buffalo, Atlanta, Northern Ireland and finally Washington, D.C., with stints in between as mayoral chief of staff, a real estate developer COO and a fellow at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

Seven years ago, at age 60, my career took a sharp left turn. An Atlanta acquaintance, a pastor, had moved to Washington, D.C., to head the United Methodist Church’s global social justice agency. She needed help with strategic planning, fundraising, investments, communications and properties, including a building directly across from the U.S. Capitol and the Supreme Court. So, off I went to learn about human trafficking, environmental justice and world peace, all topics I cared about but had zero experience working on.

Three years later, I accepted an assignment within the church family to move to New Jersey to lead a United Methodist-affiliated organization to develop strategies for its $500 million in church real estate spread across the state.

Then COVID hit. My job shifted from real estate to emergency management. I coordinated the raising of $8 million in federal funding for 530 churches and strived to keep food pantries and other human services in operation. It was time for my husband and me to return to the Washington, D.C., area, where I reactivated my consulting firm to work on economic development, especially with church governing bodies and municipalities.

A Building by Any Other Name

Decisions made by lay leaders and clergy often rely more on emotion than logic, understandably so. No one wants to downsize or close the institution from which they were married, their parents were buried or their children were baptized.

Yet one cannot ignore the numbers. Church property costs $7 to $10 per square foot annually to operate — $70,000 to $100,000 for a modest 10,000-square-foot property. A congregation with a median age of 75 will soon find itself shy of members. Spending a quarter of the organization’s cash reserves year after year is unsustainable, no matter how well the investment portfolio performs. Giving short shrift to the data often results in sudden, sad decisions to close and pound a “for sale” sign in the front lawn, with little forethought.

Some might say, “Let churches close. Let the market decide highest and best use of their real estate.” In high-demand real estate markets, such a philosophy can result in a missed opportunity to develop affordable housing or offer human services or arts and culture to an entire neighborhood.

In low-demand markets, public intervention may be required to preserve a historic asset or prevent a community eyesore.

How can houses of worship maximize the full potential of their properties? Thanks to creative individuals who often have had to push uncomfortable hierarches to think differently, there is hope. Some Christian organizations have definitely thought outside the box. Centre St. Jax, an Anglican church in Montreal, has been redeveloped to provide space to community organizations, including an agency serving immigrants, a food bank, a circus cabaret and a circus school. The Village @ West Jefferson in Louisville, Kentucky, a property of St. Peter’s United Church of Christ, is a new 30,000-square-foot mixed-use office and retail development in the historic Russell neighborhood.

A current example near the Rice campus, St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church has issued a request for proposals to reconceptualize their property into a mixed-use development in Houston’s bustling Montrose neighborhood. Doing so will not only ease the church’s financial condition; it will integrate the church better into the city.

As encouraging as these success stories are, the challenge is how to take this sort of work to scale. Strategies that work for one or two churches may not work for 100,000.

We desperately need to shape a new model for houses of worship. The church sitting isolated, surrounded by a fence, used only a few hours a week, abutting an empty parking lot, unable to deliver state-of-the-art, online services is not good use for either the faith institution or the community. The answers have to do with consolidation and mixed use.

Rev. Dr. Thomas Edward Frank, dean emeritus at Wake Forest University, and I focus on three major shifts needed for houses of worship to be successful. First, the need to move from private to public — the buildings should be seen as the community’s asset, not the congregation’s club. Second, the need to move from simple to complex — thinking of these houses not only for Sunday worship for one group, but also for daily use by multiple groups. And third, moving from static to dynamic — what worked yesterday probably won’t work today.

Jane Jacobs (urbanist and author of 1960’s seminal “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”) identifies four factors critical in creating great cities: mixed uses, short city blocks, aged buildings and high density. Most houses of worship fail miserably at three of the four. (They’re old, but that’s it.) That needs to change.

What emptying department stores were to the late 20th century, emptying houses of worship are to our era except, thanks to the intricacies involved, the problems are greater and the opportunities more limited.

The issue is complex, will evolve over time, and will take open minds and the strategic thinking of pastors, planners and business leaders to move our small towns forward. So, when you pass a “for sale” sign at that closed church, temple or synagogue down the street, I urge you to take a moment to mourn what was. But then imagine what could be, for our congregations and the communities they call home. ⚜

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Falling Stars

How to future-proof your brand reputation.

Company reputations are more precious and precarious than ever. How can organizations insulate themselves from a world of constant controversy?

Warren Buffett famously prioritizes reputation over profit. In a 2014 memo to his Berkshire Hathaway management team, he wrote: “We can’t be perfect but we can try to be. As I’ve said in these memos for more than 25 years: ‘We can afford to lose money — even a lot of money. But we can’t afford to lose reputation — even a shred of reputation.’”

Buffett’s words still hold true. If anything, reputation has become a more dynamic and delicate asset over time. In today’s heated and fast-paced environment of 24-hour news cycles and social media algorithms, perceptions of any given company seem to be in constant jeopardy. This is especially true for industry leaders like BP, Starbucks and United Airlines. The bigger a brand becomes, the more exposed it is to public scrutiny.

To quote Buffett once again: “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently.” Given today’s increasingly spiky landscape of consumer feedback, it can take closer to five seconds for organizations to lose ground. So, how should they be doing things? How has the art of reputation management evolved? How can companies achieve the effect that Rice Business professors Vikas Mittal and Utpal Dholakia call “brand insulation?” And what can we learn from prominent cases of reputational recovery?

The Toyota Crisis

Rankings, ratings and crisis responses: They’ve become essential to the way outsiders perceive an organization’s identity and character. These days, brand favorability can rise and fall with a single tweet. But 140 characters is not much room for nuance. As recent controversies at Adidas and Ticketmaster prove, reputations are more complex than social media and one-star reviews make them seem. According to YouGov’s BrandIndex, when Adidas cut ties with Kanye West in October 2022, brand consideration metrics increased by 6% in the U.S. — but decreased by the same amount in the U.K. And when Ticketmaster botched the sale of tickets for Taylor Swift’s “Eras Tour” in early 2023, customers and Congress expressed outrage. But shareholders shook it off. Company revenue increased by 73%, and Live Nation stock rose by 15%.

Our rating systems and fast-paced communications are useful for many things. But it’s difficult to read them for the broader contexts of public perception, especially as PR crises unfold in real time. To gain a clearer perspective of company reputation as a modern asset, it’s helpful to examine the rise and fall of an older case.

Consider the Toyota recalls of 2009-2011, one of the most extreme reputational setbacks in living memory. Within months of overtaking General Motors to become the number one automaker in global sales, the Japanese company collided with a public relations fiasco. It was the kind of disaster that strikes the heart of a brand’s identity — in Toyota’s case, a reputation for car reliability and safety.

The crisis started with an unintended acceleration tragedy in California. In August 2009, four family members were heading to a women’s college soccer game in a loaner Lexus ES350. (Lexus is a division of Toyota.) Along the way, the car began speeding uncontrollably. By the time a backseat passenger called police, 52 seconds before their fatal crash, the car was careening 120 mph through one of the busiest intersections in San Diego County. Doing his best to describe their awful situation, the caller explained, “Our accelerator is stuck … We can’t … There’s no brakes.”

The deadly incident was shocking. Audio from the 911 call went viral. The story was headlined on evening news channels. People became frightened — not of driving, per se, but of the company that seemed responsible for this family’s tragedy. Every Toyota-related traffic incident took on a larger significance. And a frenzied U.S. media couldn’t resist magnifying the contrast between the company’s sterling reputation, the violence of this horrible incident, and the eye-popping number of cars that Toyota would recall, piecemeal, in the weeks and months to come. At its peak, Toyota’s reputation crisis was the second-highest covered story in the U.S., ahead of the 2010 Haiti earthquake that killed more than 200,000 people.

As it turned out, in the case of the California fatalities, the dealer who loaned the Lexus sedan had improperly installed an all-weather SUV floor mat. When the incorrect and unsecured floor mat slipped, it trapped the accelerator — a design vulnerability that was not unique to Toyotas. And with the driver feeling panicked in an unfamiliar vehicle, the situation was a recipe for tragedy.

In terms of the large-scale panic that emerged from this incident, a 10-month NASA investigation determined “pedal misapplication” (i.e., driver error) to be the leading cause of unintended acceleration in Toyota cars. And National Public Radio learned that during the years in question, other car companies received significantly higher rates of complaint about the issue than Toyota.

Like countless PR emergencies that had come before it, concern about unintended acceleration in Toyotas cooled over time. As attention waned, public analysis shifted from the company’s reputation to the media’s hysterical response. But even with the benefit of this belated self-reflection, it took Toyota years to recover from the outbreak of provocative headlines. In 2021, the company achieved a major milestone, surpassing GM to become the bestselling automaker in the United States. But if not for their reputation crisis 10 years prior, perhaps they would have achieved that breakthrough long before.

The Fragility of Influence

We can learn a lot from debacles like the one Toyota endured — perhaps especially about the public psychology of brand reputation audits.

Rice Business Professor Anastasiya Zavyalova is often called “the scholar of scandal.” When discussing her research, she’s quick to note that no two controversies are the same. The Toyota ordeal was unique in many ways. For instance, perceptions were likely influenced by watershed events such as a global recession and a controversial government bailout of U.S. automakers.

But in at least one important way, the recall crisis was emblematic of a fast-paced culture with an appetite for fall-from-grace narratives: Toyota’s perceived technical issue evolved very quickly into a debate about company character. As Zavyalova says, “The narrative went from being about accelerator pedals to the problem of Toyota being an unethical company — that they cut costs by playing with people’s lives.”

According to Zavyalova, consumers are much more likely to forgive incompetence than impropriety. But on social media and 24-hour news, questions of impropriety elicit stronger audience engagement. PR disasters can certainly involve elements of both product quality and company integrity. But in today’s public discourse, distinctions are eroding between these categories. For example, when organizations respond to an incident too slowly or inauthentically, online conversations rapidly morph into disputes over brand persona. In today’s speedy and crisis-hungry culture, questions of competence quickly become interrogations of ethos. And government officials are trained to lead the charge; otherwise, they risk seeming complicit or complacent.

Given the violent loss of life in Toyota’s case, it was perhaps inevitable, even understandable, that the firm would undergo a holistic reputation check. But after decades of prioritizing quality and reliability, it also seems reasonable that Toyota would want to distinguish a question of product defects from a debate about company principles.

In the early stages of the accelerator crisis, Toyota must have believed their trouble was purely technical. They initially denied systemic safety concerns, and in doing so amplified a public outcry and mobilized Congress. When it became clear that their PR damage was coming from the direction of company character rather than strictly machine performance, Toyota pivoted to recall millions of vehicles.

The societal impulse to interrogate corporate morals and practices is, of course, neither new nor inherently cynical. From the Montgomery bus boycott to conflict-free diamonds, business protests have led to some of the world’s most impactful social changes.

But in the last 10 to 20 years, with political divides widening and quicksilver connections climbing, companies have become increasingly liable to misinterpretation, speculative bias and volatile voices.

Rice Business Professor Alessandro Piazza studies stigma and scandal across organizations. He calls social media a “catalyzing factor” for PR debacles — an idea that dovetails with MIT Sloan research that finds falsehoods are 70% more likely to be shared online than truths and can spread six times more quickly.

“These days,” Piazza says, “organizations are granted less time to respond and have less control over the narrative. And perhaps more importantly, the rapid exchange of unhelpful internet chatter can interfere with genuine efforts to create positive change.”

For major business-to-consumer (B2C) firms like Meta, Netflix and Uber, reputation has become an especially delicate asset. Zavyalova and Piazza suspect this is because such companies influence our shared imagination. The more space these brands occupy in our collective consciousness, the more exposed they become to public judgment. And because B2C giants profit from and are integral to our class identities, it makes sense that consumers use emotive words like “love” and “hate” to deliberate them. Major B2Cs are often an extension of how we see ourselves and one another.

In her recent interview for “Owl Have You Know” (the award-winning Rice Business podcast), Zavyalova says that “the gap between a company’s internal and external personas is shrinking.” Consumers no longer passively digest information. They engage in real time and have a more powerful voice.

As Piazza notes, this dynamic has its benefits, but it can be a double-edged sword. Because our culture thrives on controversy, social media and 24-hour news chyrons can impede organizations from assessing the impact and scope of any given problem. Worse, they can distract from focusing on empathy for affected individuals and communities.

If consumers slow down to reflect on these fast-paced forces, they will surely see social and even economic benefits. (For example, taxpayers funded the lengthy NASA investigation that identified driver error as Toyota’s primary cause of unintended acceleration.) But as things stand, our speedy and polarizing communications landscape makes the tightrope of reputation management tenuous enough to give the most skilled PR specialist vertigo.

Is there any good news?

Future-Proofing Your Brand

In a word, yes. At the height of the Toyota crisis, Rice Business Professors Vikas Mittal and Utpal Dholakia posed a question in Harvard Business Review: “Does media coverage of Toyota recalls reflect reality?”

What they found disputed the notion that Toyota was experiencing a “crisis” at all — at least in terms of reputation.

Surveying 455 U.S. vehicle owners, 13% of whom owned Toyotas, Dholakia and Mittal learned that Toyota customer satisfaction remained level with those of other automakers. In fact, customers interpreted the massive recalls as a company commitment to safety and reliability.

In other words, even though a heightened media response turned Toyota’s technical crisis into a debate about company character, customers reinforced their loyalty to the brand.

What can explain this?

According to Dholakia and Mittal, Toyota benefited from what they call the “brand insulation effect.” Insulated brands have a loyal and attentive customer base who will advocate for them in situations of lapsed quality — so long as the company does all it can to fix the problem. These customers will disregard negative information and support alternative explanations. They are more likely to strengthen their commitment to the organization than diminish it. (We often see a similar circle-the-wagons impulse in politics, religion and sports.)

“Brand insulation” offers a framework for future-proofing a company’s character narrative. But achieving it requires more than product excellence. Toyota, Apple and Disney have high-commitment customers, Mittal argues, because they offer “an amazing buying experience, service experience and online content in terms of simplicity and connectivity.” Little things make a big impact, even if customers take them for granted. The bathrooms at Disney World are always clean. You can purchase an Apple device without standing in line.

To achieve brand insulation status, companies must deliver two things over a long period of time: a high level of customer satisfaction and, more importantly, a consistent level of customer satisfaction. And these two outcomes can really only occur by adhering to Warren Buffett’s edict to prioritize reputation over profit.

Perhaps this is where Toyota went wrong, for a time. At one point in their 2009-2011 crisis, company president Akio Toyoda acknowledged that they had lately confused the order of their traditional priorities, putting growth ahead of quality. But with the benefit of brand insulation, Toyota was able to examine their internal processes and recommit to prioritizing excellence without losing customers. Toyota owners were certainly aware of the recalls. But as customers of an insulated brand, they disregarded media exposure and trusted their long-term memories. Decades of high and consistent satisfaction protected the company.

Mittal and Dholakia’s concept of brand insulation pushes back a bit on Buffett’s dogma that firms cannot afford to lose a shred of reputation. The Toyota episode shows it is possible to shield a company against even the most colossal of PR disasters. But it can only happen by prioritizing a record of all-around excellence.

Brand insulation represents good news for consumers, as well: Toyota’s crisis proves that supercharged media reactions do not necessarily influence or reflect customer perception. The panics we observe on a screen are not always panics in truth. ★

Lessons Learned:

Warren Buffett’s philosophy is as old as Shakespeare, who wrote, “The purest treasure mortal times afford is spotless reputation.” A damaged reputation is difficult to rebuild, especially in the digital age. Doing so requires a concerted effort to regain trust, rectify mistakes and demonstrate a renewed and ongoing commitment to customer satisfaction.

But Toyota and other major PR disasters demonstrate that insulated brands can endure the storms of controversy. By prioritizing exceptional experiences and consistent quality, companies can forge a loyal and attentive customer base that will remain committed in times of crisis.

When ratings and reputation metrics fall — a virtual certainty in today’s world — company leaders must act quickly and respond authentically. But even more important: They must prioritize a culture of excellence from the outset. By putting long-term integrity ahead of short-term gain, organizations can strive to build a brand that withstands the test of time.

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Rice students win commodity competition at University of Houston

Four Rice students took the top prize and $2,000 in cash at the University of Houston’s Undergraduate Commodity Competition Sept. 9. The event allows undergraduate students from across the nation to demonstrate their proficiency in commodity knowledge and investment research and present to a panel of judges from top firms in Houston.

Four Rice students took the top prize and $2,000 in cash at the University of Houston’s Undergraduate Commodity Competition Sept. 9. The event allows undergraduate students from across the nation to demonstrate their proficiency in commodity knowledge and investment research and present to a panel of judges from top firms in Houston.

Andrew Pitigoi, Evan Pitigoi, Marco Stine and Caleb Stocking represented Rice against 14 teams from other schools, many of which boast specialized trading programs. The objective of the contest was to pitch the best investment strategy and defend it against scrutiny. The Rice team’s strategy? A bold short on Brazilian corn futures.

“Despite the absence of a dedicated trading program at Rice, the team’s rigorous research, meticulous due diligence and countless hours refining their pitch paid off,” said Stocking, who is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in finance with a minor in data science.

The Rice students’ performance not only won the competition but also garnered praise from both UH’s Bayou Capital Group leadership team and the panel of seasoned traders from top-tier firms.

You May Also Like

Rice University’s Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business today announced the launch of its Graduate Certificate in Healthcare Management program, a 10-month, credit-bearing professional credential designed for current and aspiring leaders seeking deep expertise in the business of healthcare.

MBA Salary to Tuition Ratio

Deciding to get your MBA is a major decision. Rice Business ranks highly on this list of business schools with the best Full-time MBA median starting salary to total out-of-state tuition from the Georgia Tech Scheller College of Business.