Leaders who show their humanity are viewed more favorably, says Rice U. expert

During a crisis, outsiders view a leader who voices both anger and sadness, or even sadness alone, as more effective than a leader who shows only anger, according to newly released research conducted at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business.

During a crisis, outsiders view a leader who voices both anger and sadness, or even sadness alone, as more effective than a leader who shows only anger, according to newly released research conducted at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business.

Brent Smith, the senior associate dean for executive education and an associate professor of management and psychology in organizational behavior at the Jones School, is available to discuss the study and its implications.

Even in the digital age, the public responds best to leaders who show their humanity, according to the research from Smith and his colleagues. The team explored how specific emotions from leaders resonate with people during a crisis.

The study polled 322 employees from different companies after they had read a newspaper article featuring company leaders involved in a product recall.

Existing literature in organizational psychology holds that a leader who shows anger during a crisis conveys competence, strength and intelligence, and a leader who expresses sadness in the same situation conveys remorse, sympathy, warmth and affiliation. The team wondered whether leaders who express both would be evaluated more favorably.

“Most subjects indeed factored the leader’s public display of emotion into their assessments of her or him,” Smith wrote. “In addition, the subjects reacted more favorably to leaders who publicly voiced both anger and sadness, or even sadness alone. A leader who showed anger alone, the subjects said, seemed less effective.”

Prior to joining the Jones School, Smith was a faculty member at London Business School and Cornell University, where he taught in the School of Industrial and Labor Relations and the Johnson Graduate School of Management. He has also taught at the University of California, Berkeley; Oxford University; the Technical University of Denmark and the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad. He has conducted executive education programs around the world for companies such as Shell, IBM, HSBC, Credit Suisse and Barclays.

A radio and television studio is available at Rice for media outlets that want to schedule an interview with Smith. For more information, contact Avery Franklin, media relations specialist at Rice, at averyrf@rice.edu or 713-348-6327.

Related materials:

Chain Reaction

How protest tactics end up influencing protesters.

Based on research by Alessandro Piazza, Dan Wang and Sarah A. Soule

How Protest Tactics End Up Influencing Protesters

- Social movements have proliferated over the last decade — and with them, the need to better grasp how they develop.

- Much of their growth comes from tactics that create a sense of collective identity, from protests to petition drives to online mobilization.

- At the same time, efforts to grow inadvertently unleash infighting and division — leading many social movements to flounder.

Brexit, Tea Party, Arab Spring. Black Lives Matter and MeToo. Protests in Hong Kong, Chile, Paris, Beirut, Baghdad and Barcelona. In recent years, the depth and variety of global social protest has exploded.

How did these movements grow and strengthen — and what are the perils that sometimes ruin them? In a recent paper, Rice Business professor Alessandro Piazza joined Columbia University’s Dan Wang and Stanford University’s Sarah A. Soule to analyze the dynamics of the movements shaping our times.

To do it, they scrutinized existing research on today’s golden age of social protest. The three researchers reviewed roughly 120 academic papers and other source material, comprising the total relevant literature about protest tactics.

First off, the researchers noted, social movements don’t develop in a vacuum: Many current movements have given a voice to an aggrieved group by speaking with a collective identity. Movements such as Brexit or MeToo, for example, express protestors’ rejection of unwanted actions from others.

Yet both Brexit and MeToo have varied memberships and include a mix of political and social outlooks as well as a range of ethnicities, nationalities, social classes, ages and even genders. What brings such protest movements together, Piazza and his colleagues write, is their “tactical repertoires” — the array of techniques they use to reach their goals.

To be sure, people with grievances have many ways to make their cases. But specific actions carry their own cultural meaning, and this meaning helps bind members of diverse groups together. A particular protest movement’s repertoire might emphasize demonstrations, strikes, sit-ins, flash mobs or artistic performances. Each of these tactics draws outside attention — and also heightens solidarity within the movement.

Tactical gestures have become especially important in recent years, because so much activism begins and coalesces online. A Twitter hashtag, a Facebook group, hacking into online networks — all have become tools that help social movements strengthen and grow. Through the power of social media, tactical approaches often resonate well beyond the first people to use them. As a result, techniques are often similar throughout an entire movement, sometimes across continents.

In November 2019 in Chile, for example, activists protesting rape culture started publicly performing a dance called “A Rapist in Your Path.” It quickly spread to Argentina, Colombia, Spain, the U.K., the U.S. and Turkey and became a recognizable visual protest. It’s a classic example of how activist groups can adopt tactics across the globe to broaden the cultural resonance of their cause. Such tactics should be studied in much greater detail, Piazza and his colleagues note.

At the same time, tactics may not be enough to keep a movement afloat. In 1966, for example, the Red Guard youth movement in China was beset by a snarl of factions that, together, harmed the movement’s larger effectiveness. Similarly, in “Homage to Catalonia,” George Orwell brilliantly documents how during the Spanish Civil War the anti-fascist forces broke down into irreconcilable groups, allowing dictator Francisco Franco to easily defeat them. More recently, the organizers of the Women’s March on Washington had to battle internal factional differences to pull off their event. In other words, sometimes the very effort to unite large groups for a cause can imperil meaningful social change.

Regardless of such challenges, social movements continue to express themselves in creative new ways. Piazza and his colleagues’ insight is how these tactics have powerful dual roles: both as messaging tools and as membership badges that heighten the loyalty of those who use them.

Alessandro Piazza is an assistant professor of strategic management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Wang, D., Piazza, A., & Soule, S. A. (2018). Boundary-spanning in social movements: Antecedents and outcomes. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 167–187.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

People, papers and presentations

Members of the Ajayan Research Group led by Rice graduate student Kimmai Tran were among the “highly commended” teams recognized by UNESCO and the World Federation of Engineering Organizations’ first annual World Engineering Day Young Engineers Competition.

Members of the Ajayan Research Group led by Rice graduate student Kimmai Tran were among the “highly commended” teams recognized by UNESCO and the World Federation of Engineering Organizations’ first annual World Engineering Day Young Engineers Competition. The competition highlighted work by engineers age 35 and under committed to advancing the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. The Rice team entered its lithium-ion battery recycling project, featured in a Rice News story and video, and was selected to compete at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, an event that was subsequently canceled over coronavirus concerns. Competition details and a list of winners are available here: https://worldengineeringday.net/young-eng2020/.

Rice’s Jones Graduate School of Business made U.S. News and World Report’s Best Grad Rankings for 2021. The Jones School tied for No. 25 on the Best Business Schools list and tied for No. 13 for its Part-Time MBA. The rankings take into account the quality of students, faculty and other resources in the education process.

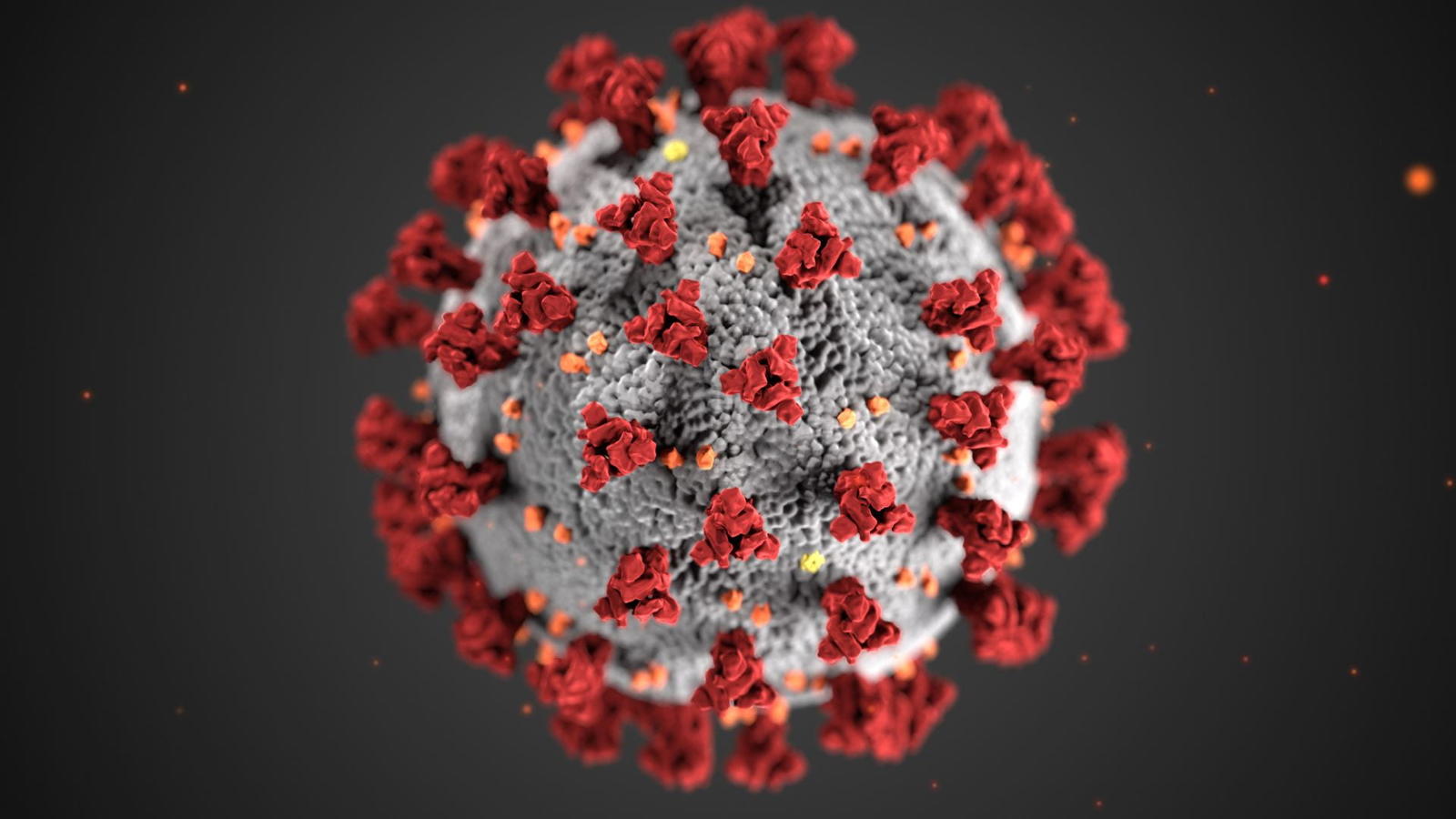

Rice U. experts available to discuss COVID-19’s wide-ranging impact

Utpal Dholakia, a professor of marketing at Rice’s Jones Graduate School of Business, is available to discuss consumer behavior and panic-buying during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Everyone is panic-buying, not just all over the country, but basically all over the world,” Dholakia said.

As the COVID-19 pandemic grows and impacts the lives of people across the globe, Rice University experts are available to discuss various topics related to the disease.

– Joyce Beebe, fellow in public finance at Rice’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, can discuss paid leave programs.

“COVID-19 highlights the importance of paid (sick) leave programs to workers,” she said. “The issue is not whether we should have a paid leave program; it is how to design a program that provides nationwide coverage to all American workers instead of waiting until the next pandemic.”

– Robert Bruce, dean of Rice’s Glasscock School of Continuing Studies, is an expert in online and distance learning, community education and engagement and innovative models for personal and professional development programs.

“The field of continuing and professional studies is uniquely positioned to help the public during a crisis that requires social distancing,” he said. “Our core mission is to empower people to continue to learn and advance, regardless of location or age or learning style.”

– Utpal Dholakia, a professor of marketing at Rice’s Jones Graduate School of Business, is available to discuss consumer behavior and panic-buying during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Everyone is panic-buying, not just all over the country, but basically all over the world,” Dholakia said. “That makes the sense of urgency even more. Are all these suppliers going to be able to keep up with the demand?”

– John Diamond, the Edward A. and Hermena Hancock Kelly Fellow in Tax Policy at the Baker Institute and an adjunct assistant professor in Rice’s Department of Economics, can discuss the economic impact on Houston and Texas, particularly unemployment.

– Elaine Howard Ecklund, the Herbert S. Autrey Chair in Social Sciences, professor in sociology and director of Rice’s Religion and Public Life Program, studies the intersection of science and religion. She can discuss how these two entities can work together to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and recently authored an editorial about this topic for Time magazine. It is available online at https://time.com/5807372/coronavirus-religion-science/.

– Christopher Fagundes, an associate professor in the department of psychological sciences, is available to discuss the link between mental and immune health.

“In my field, we have conducted a lot of work to look at what predicts who gets colds and different forms of respiratory illnesses, and who is more susceptible to getting sick,” Fagundes said. “We’ve found that stress, loneliness and lack of sleep are three factors that can seriously compromise aspects of the immune system that make people more susceptible to viruses if exposed. Also, stress, loneliness and disrupted sleep promote other aspects of the immune system responsible for the production of proinflammatory cytokines to overrespond. Elevated proinflammatory cytokine production can generate sustained upper respiratory infection symptoms.”

And while this research has centered on different cold and upper respiratory viruses, he said “there is no doubt” that these effects would be the same for COVID-19.

– Mark Finley is a fellow in energy and global oil at the Baker Institute.

“The U.S. and global oil market is simultaneously grappling with the biggest decline in demand ever seen (due to COVID-19) and a price war between two of the world’s largest producers, Russia and Saudi Arabia,” he said.

– Bill Fulton, director of Rice’s Kinder Institute for Urban Research, an urban planner, an expert on local government and the former mayor of Ventura, California, can speak to both the short-term and long-term changes in city life and the way government works.

"What will the effect be on transportation and transit? Retail and office space? Will people walk and bike more? How will they interact in public spaces in the future? How will government function and hold public meetings during the crisis, and will this fundamentally alter the way government interacts with the public in the long run? How will local governments deal with the inevitable revenue loss — and, in the long run, with the fact that they will probably have less sales tax?"

– Vivian Ho, the James A. Baker III Institute Chair in Health Economics, director for the Center of Health and Biosciences at the Baker Institute and a professor of economics, can discuss insurance coverage as families experience lost income and jobs during the crisis.

“Policymakers should temporarily expand subsidies for middle class workers who buy insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplace,” Ho said. “Families experiencing lost income due to the pandemic shouldn’t have to worry about losing access to health care in the midst of a pandemic.”

“Hospitals in states that did not expand Medicaid coverage to able-bodied adults under the Affordable Care Act are bearing tougher financial burdens, which may damage their ability to respond to the current health crisis,” she said.

– Mark Jones, a professor of political science and fellow at the Baker Institute, is available to discuss how the spread of COVID-19 is impacting elections, including runoffs in Texas.

“COVID-19 has already resulted in the postponement of local elections originally scheduled for May 2, with the elections now to be held in November with current officeholders’ tenure extended until their successors are confirmed in November,” Jones said. “It is increasingly likely that COVID-19 will affect the Democratic and Republican primary runoff elections scheduled for May 26, with a growing possibility that the elections will be conducted entirely via mail ballots or at the minimum will involve the adoption of no-excuse absentee voting whereby any Texan, not just those 65 or older, hospitalized or out of the county, will be able to obtain an absentee ballot and vote by mail.

“The emergency adoption of no-excuse absentee voting would change the composition of the May primary runoff electorate by expanding turnout among many voters who otherwise would have been unlikely to participate, as well as increase pressure on the Texas Legislature to reform the state’s electoral legislation to allow for no-excuse absentee voting when it reconvenes in January of 2021 for the next regular session.”

– Laura Kabiri, a lecturer in Rice’s Department of Kinesiology, can discuss staying active during social distancing, and how adults and children can get enough physical activity and/or work out at home.

“Physical activity is good for your physical, mental and emotional health,” Kabiri said. “Exercise decreases stress, boosts your immune system and can lead to the release of your own endogenous opioids to decrease pain, relieve anxiety and improve your mood, all without pills or their side effects.

“If you already exercise on a regular basis, keep it up,” she said. “Even without a gym, you can get a great workout at home. Water bottles and jugs make terrific weights and that deep freezer is great for modified push-ups and tricep dips. Can’t make your Zumba class? Have a family dance party in your living room to streaming music videos or dust off the old LPs.

“However, this is not the time to overdo or attempt new feats of strength,” she said. “Abusing your body can actually harm your immune system, and no one wants to end up in an already overcrowded ER with a hernia.”

– Danielle King, an assistant professor of psychological sciences and principal investigator of Rice’s WorKing Resilience Lab, is an expert on the topic of resilience to adversity. Her research focuses on understanding the role individuals, groups and organizations play in fostering adaptive sustainability following adversity. She can discuss how individuals can remain resilient and motivated in difficult circumstances.

“Though we are still in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, we can begin to enact adaptive practices that foster resilience such as remaining flexible to changing circumstances, practicing acceptance of the present realities, seeking social support in creative ways while practicing social distancing, and finding and engaging with experiences and thoughts that elicit positive emotions during trying times,” King said.

– Tom Kolditz, founding director of Rice’s Doerr Institute for New Leaders, is a social psychologist and former brigadier general who has done extensive research on how best to lead people under perceived serious threat. His work is widely taught at military service and police academies globally, and he did extensive work with the banking industry during the 2008 financial crisis. His expertise is in articulating what people need from leaders in volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous times and what leaders must do to gain and maintain people’s trust. His book, “In Extremis Leadership: Leading As If Your Life Depended On It,” teaches people to lead in crisis, when people are anxious or afraid.

“Leadership when people are under threat hinges far less on managerial principles, and far more on trust,” Kolditz said. “Whether in a company or their own family, people who lead in the same way now as they did two months ago will experience a significant decline in their influence.”

– Jim Krane, the Wallace S. Wilson Fellow for Energy Studies at the Baker Institute, is an expert on energy geopolitics and Middle East economies and societies. He can comment on the effect on OPEC and its production decisions, relations between Russia and Saudi Arabia, and how low oil prices will affect policy inside producer countries.

– Ken Medlock, the James A. Baker III and Susan G. Baker Fellow in Energy and Resource Economics at the Baker Institute, senior director of institute’s Center for Energy Studies and an adjunct professor and lecturer in Rice’s Department of Economics, can discuss COVID-19’s impact on oil prices and the oil industry.

– Kirsten Ostherr, the Gladys Louise Fox Professor of English and director of Rice’s Medical Futures Lab, can discuss the representation of outbreaks, contagion and disease in public discourse and the media. She is also an expert on digital health privacy. She is the founding director of the Medical Humanities program at Rice, and her first book, “Cinematic Prophylaxis: Globalization and Contagion in the Discourse of World Health,” is one of several titles made available for open-access download through June 1 by its publisher, Duke University Press.

– Peter Rodriguez, dean of the Jones Graduate School of Business and a professor of strategic management, can discuss the economic impact of COVID-19 in Houston, the state of Texas and around the world.

– Eduardo Salas, professor and chair of the Department of Psychological Sciences, is available to discuss collaboration, teamwork, team training and team dynamics as it relates to COVID-19.

“We often hear that ‘we are in this together’ and, indeed, we are,” Salas said. “Effective collaboration and teamwork can save lives. And there is a science of teamwork that can provide guidance on how to manage and promote effective collaboration.”

– Kyle Shelton, deputy director of the Kinder Institute, can discuss how the economic impact of COVID-19 closures and job losses can amplify housing issues, and why governments at every level are opting for actions such as halting evictions and foreclosures and removing late fees. He can also speak to some of the challenges confronted by public transportation, why active transportation like biking and walking are so important now, and how long-term investments in these systems make cities and regions more adaptive and resilient.

– Bob Stein, the Lena Gohlman Fox Professor of Political Science and a fellow in urban politics at the Baker Institute, is an expert in emergency preparedness, especially related to hurricanes and flooding. He can also discuss why and when people comply with government directives regarding how to prepare for and respond to natural disasters, and the political consequences of natural disasters.

“Since God is not on the ballot, who do voters hold accountable before and in the aftermath of natural disasters?” he said.

– Laurence Stuart, an adjunct professor in management at Rice Business, can discuss unemployment in Texas, how people qualify for it and what that means for employers and employees.

For more information or to schedule an interview, contact Amy McCaig, senior media relations specialist at Rice, at 217-417-2901 or amym@rice.edu.

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations on Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Photo link: https://news.rice.edu/files/2020/03/23311-1.jpg

Photo credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

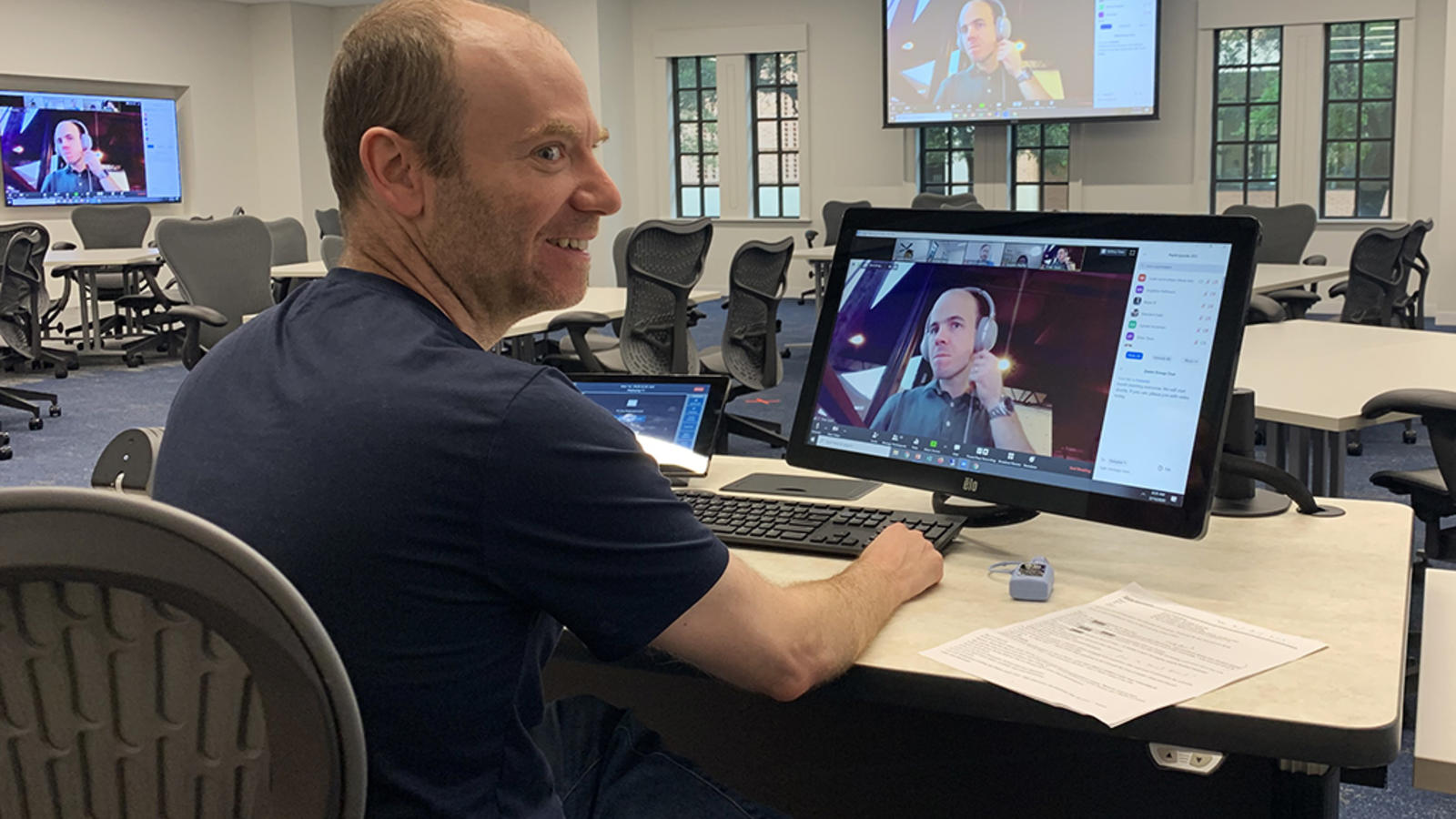

Coronavirus and the classroom: How Rice is tackling the move to remote learning

If there was ever a time for the Rice University community to step up, that time is certainly now. Rice students, faculty and staff are finishing the spring semester in unprecedented circumstances, responding to the threat of COVID-19 by hunkering down and delivering classes online.

If there was ever a time for the Rice University community to step up, that time is certainly now. From the evidence to date, it seems it is.

Rice students, faculty and staff are finishing the spring semester in unprecedented circumstances, responding to the threat of COVID-19 by hunkering down and delivering classes online.

Within a matter of days, faculty modified their courses to remote instruction, figuring out how to deliver quality higher education while sitting in front of computer screens instead of standing in front of lecture halls.

From the logistical challenges involved in delivering lectures and labs remotely to adjusting course content for the radically altered world students are now navigating, instructors and the staff supporting them are finding creative ways to continue meeting the university’s high standards for the classroom experience.

Many of them are sharing their stories, and some of their best practices, with Rice News. As electrical and computer engineer Ray Simar said after reconfiguring his class, “We could turn it into a miniseries. It has more storylines than ‘Game of Thrones.'”

Many classrooms are moving to Zoom for live instruction. Daniel Domingues, an assistant professor of history, found his Africa in the Museum course disrupted with the abrupt end of FotoFest, but found a way to integrate the course’s existing Canvas page with Zoom. “We’re going to try to continue our meetings online,” he said. “I say ‘try’ because my wife and I live with a 3-year-old in a tiny apartment and the little one isn’t very cooperative.”

Chemist László Kürti declared himself ready as well, and added a twist. “I have now practiced sharing the notepad feature of iPad where I can use the Apple Pencil and draw chemical structures and interact with the students,” he said.

English professor Joe Campana noted a benefit of teaching adults in his Glasscock School master’s course, Exploring the Arts, is that many already use Zoom at work. He said one student who manages Zoom calls at her workplace quickly wrote a handy guide. “We got really lucky,” he said. “We’re a small group, so that helps, and we’d already bonded in a number of different ways weeks ago, and that’s partly because we went to live performances together.”

Economic chair George Zodrow called in the cavalry to get classes up and running online, putting faculty members Jimmy DeNicco and Mahmoud El-Gamal in charge of the Social Sciences Transition Resource Team. “Jimmy has a great deal of experience with the online teaching of our Principles of Economics course and Mahmoud, who is our director of undergraduate studies, is also one of our more tech-savvy faculty members,” Zodrow said. “Mahmoud recently was able to benefit from the extraordinary support of Rice IT to get some specialized software made available to students in a matter of a few hours.”

Sports medicine lecturer Laura Kabiri learned something about herself as she organized her material for Zoom. “Immediately upon hearing that we should prepare for remote course delivery, I started recording my lectures to post online,” she said. “Unfortunately, I found myself falling asleep during my own lectures.

“No one plans for this,” Kabiri noted, “but I know Rice will analyze, improve and revolutionize the way educators and students make lemonade out of all these lemons.”

One course seemingly meant for the times, Monster by Deborah Harter and Mike Gustin, explores what humans find monstrous from a scientific and literary perspective. It took a different turn with the recognition of parallels between the course and the current crisis.

“Students come into our class thinking that the course is about vampires and Dracula and all of that,” Harter said. “And what they are often surprised to discover is that that we’re interested often in those monstrosities that are not so visible, that are in fact invisible. And that is what makes, I think, the coronavirus so frightening.”

Jones School professor Jing Zhou, who teaches graduate-level management and psychology, said detailed preparation several weeks ago has paid off in a smooth transition online for her working professional students. She’s going solo in a Jones classroom set up for remote teaching.

“I like to walk around and write things on a board, and teaching in a real classroom allowed me to hold some things constant amongst a sea of change,” she said. “I was pleasantly surprised that teaching went really well. The 60 students stayed engaged throughout the two days. … Occasionally, the students’ toddlers, dogs and cats popped in our class, bringing a smile to our faces.”

Robert Yekovich, dean of the Shepherd School of Music, noted online learning holds particular challenges for Shepherd students, given the importance of ensemble participation.

“Having to take these actions is extremely disappointing for everyone, yet we do so knowing these measures are necessary and in the near-term interests of our school community,” he said. But students and teachers are working together to fulfill their commitments. “We are committed to insuring that students scheduled to graduate are not obstructed by these unfortunate setbacks.”

Jones Professor Scott Sonenshein has particular expertise in adapting to circumstances.

“As someone who has literally written the book on resourcefulness, I put into action what I’ve spent much of my career researching,” he said of his Leadership Intensive Learning experience course. “With only a few short days to get my class online, I transitioned it with minimal disruption and took advantage of the online platform to do things I never had thought about in the classroom environment.”

The School of Social Sciences’ Rachel Kimbro actually found herself ahead of the curve with her Medical Sociology class, thinking not only about what could happen but also how it could and should be recorded for history.

“About a month ago, by student request, I jettisoned a planned class day and lectured on the coronavirus,” she said, noting that little of record remained from Rice’s experience with the 1918 flu pandemic. “I determined that we would create contemporaneous records of student experiences (and mine), influenced by course material, and contribute them at the end of the term to the Woodson Research Library and Rice’s archives, with the support of (University Historian) Melissa Kean.

“So far, the entries are wonderful — full of wistfulness about leaving Rice and concern for others.”

Panic-buyers not making rational decisions, says Rice U. consumer behavior expert

Many Americans who are worried about being able to provide food, water and other necessities for their families during the coronavirus outbreak aren’t making rational decisions, according to a consumer behavior expert at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business.

Many Americans who are worried about being able to provide food, water and other necessities for their families during the coronavirus outbreak aren’t making rational decisions, according to a consumer behavior expert at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business.

Utpal Dholakia, professor of marketing at Rice Business, is available to discuss the dynamics at play.

“Everyone is panic-buying, not just all over the country, but basically all over the world,” Dholakia said. “That makes the sense of urgency even more — are all these suppliers going to be able to keep up with the demand?”

Rather than try to find deals and stick to their normal routines, shoppers on panic sprees scoop up as much as they can, including items they might not even use, Dholakia said. They generally spend more, and some might even rack up credit card debt, harming their financial health, he added.

To schedule an interview with Dholakia, contact Jeff Falk, director of national media relations at Rice, at jfalk@rice.edu or 713-348-6775.

Follow the Jones Graduate School of Business on Twitter @Rice_Biz.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations on Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Dholakia bio: https://business.rice.edu/person/utpal-dholakia.

As Economy Is Upended, Marie Kondo Drops a Workplace Book

Our own bad habits and the natural entropy of most systems has caused misery and burnout, and attendant self-help books. Marie Kondo collaborated on this one with Scott Sonenshein, an organizational psychologist, and they take turns explaining how to tidy desks, drawers, meetings (otherwise known as activity clutter), time, inboxes, behaviors and, ultimately, careers.

Life Savings

What’s the cost of an MBA? Even for candidates who know their next step is business school, the financial commitment is significant. But you may be surprised at how affordable a Rice MBA really is.

Updated from original post that was published in 2020.

Why a Rice Business MBA is Surprisingly Affordable

What’s the cost of an MBA? Even for candidates certain that their next step is business school, the financial commitment is significant. For candidates who are still deciding, calculating the variables — tuition, time, meeting responsibilities to family, work and community — can be overwhelming. Both types of high performers may be surprised how affordable a Rice MBA actually is.

I’d like to share a range of perspectives on how accessible our programs can be for students who meet the Rice Business criteria for acceptance. As the director of financial services for Rice Business, I’m in charge of showing candidates the many options that can put this superlative education within reach. There are scholarships, financial aid, loans both within the school and outside.

The key concept to know is how individualized paying for a MBA tuition can be. That’s why it’s essential if you aspire to a Rice Business MBA to contact me. Trying to figure out tuition options without help, frankly, is daunting. I’m familiar with the whole field of possibilities for lowering business school costs — and there are many. And I am available one-on-one to find every break that’s there for you.

Student Loan Options

The first question many students have is about loans. There are two types available: federal and private. Federal loans are often times easier to qualify for; but private loans can offer better interest rates. Neither are bad options, but depending on circumstance, one might be best for you overall.

Rice Business Scholarships

Rice Business also grants an impressive roster of scholarships, largely to Full-Time MBA students: more than 75% of our full-time students will receive merit-based scholarships.

Outside the business school, there are still more scholarships available. I can help you find these. This is why I tell candidates to talk to me as early as possible when considering their Rice MBA, in order to take maximum advantage of the options out there. Business school can seem very expensive — but I’ll show you what you’ll actually pay, and especially if you’re a full-time MBA, it’s usually less than the sticker price.

Knowing this can be a decisive factor. For Barkat Syed (Full-Time MBA), scholarship support not only helped him cover tuition, it let him to devote full concentration to his studies once he got there. Thanks to a Rice Business scholarship, Syed said, “My family can rest easy knowing that I can take care of myself without my having to put anything on them.”

The Value of Getting an MBA

While considering the actual dollar amount of your education, you’ll also want to know the long-term return on this investment. In an entertaining video, Rice Business Professor James Weston does the math. Walking through the same type of equation you would use making any other major business decision, Weston shows that the ROI of a two-year business education — even without a tuition break — gives a lifetime salary ROI of 20 percent.

Interested in Rice Business?

Another important part of your business school ROI will be your preparation for the disruptions and unforeseen demands of 21st century business. That’s part of the equation for Rosalee Maffitt, a second-year student in the Professional MBA program. While this program does not have scholarship support, Maffitt chose it because she could earn her salary uninterrupted while positioning herself to advance.

“Having a career is important to me, and I knew I had specific knowledge gaps in business,” she said. “For example, I'd been in enough situations where my boss asks me to look at a company's financials to deliver a brief, where more formal training would be helpful.” A former professor suggested Rice Business, because she wouldn’t have to leave the workforce to advance through higher level skills and a new network. In fact, Maffitt said, her Rice Business professional cohort has been one of the program’s most distinctive benefits, thanks to her classmates’ life and work experience.

“The world is changing more quickly than ever,” Maffitt said. “What made me successful 10 years ago will not necessarily make me successful 10 years from now. I firmly believe having robust and strong professional skill-sets are necessary to adapting to change and having more professional choices.”

An Affordable MBA for All Students at Rice Business

For first-generation Americans, women and underrepresented minorities, the selection of tuition options is excellent, said Lina Bell, executive director of belonging and engagement at Rice Business. “Rice Business is not out of people’s reach financially. If you are a competitive applicant who meets the Rice Business criteria, it is likely that it will be financially possible for you,” she said. “We trade on potential. So if you have the leadership, the academic chops and leadership potential — there is funding available.”

Some of this funding, Bell said, comes in partnership with national groups promoting diverse student bodies: Among these are The Forte Foundation, and The Consortium.

“It’s just a whole world of options out there,” Bell said. “Once you take advantage of these opportunities, your Rice MBA can change the trajectory of your career. It can be exponential in terms of your professional success. It can change who you are in the world.”

You May Also Like

MBA Class of 2020 Faces Tough Summer or Worse as Recession Looms

Recruiting for some industries generally starts early in an MBA’s second year. By February, about 60% of students will normally have offers, says Philip Heavilin, executive director of career development at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business in Houston. By graduation in May, 80% will have a job. The experience of the class of 2020 could show a sharp contrast between those who secured positions before the virus-triggered market crash, and those hunting for work afterward, he says.

The Paradox of Successful Overseas Investments

The very traits that make global growth possible — size, age and ownership — can also make cultural distance harder to overcome.

Based on research by Yan Anthea Zhang (Rice Business), Yu Li, and Wei Shi

Key findings:

- Expanding into foreign markets is tempting, but strategic fit can determine success or disaster.

- Three company characteristics strongly affect the fate of expansion into a distant or culturally different country: age, size, and state versus private ownership.

- Paradoxically, firms with the resources to handle geographical distance lack the resources to manage cultural distance — and vice versa.

You built your business from the ground up, patiently finding techniques and products that work, carefully crafting solid bonds with your clients. Then one day a new project, opportunity or simple request poses a question: Is it time to branch out overseas?

Of the welter of questions to consider, the first and most important involves location: not just the physical location of the prospective expansion site, but the cultural differences between a firm’s home country and its new destination. Secondly, key company traits need to be considered in choosing the investment locations. Is your firm large or small? Young or old? Finally, of pivotal importance to companies outside the United States: Is your company privately held or state-owned?

In a recent paper, Rice Business professor Yan Anthea Zhang looked closely at these three variables with Yu Li of the University of International Business and Economics Business School in Beijing, China and Wei Shi of the Miami Business School at the University of Miami. What, the researchers wanted to know, was the relation of these three features and firms’ location choices for their overseas investments?

To find out, Zhang and her colleagues analyzed 7,491 Chinese firms that had recently ventured into foreign markets with 9,558 overseas subsidiaries. Because China now has become the world’s leading source of foreign direct investments, the sample promised to be instructive. Thanks to the large sample size, researchers could test hypotheses relating to firm size, age, ownership and the impact of geographical and cultural distance on their location choices.

After studying the elements of geographic distance and cultural distance, Zhang and her colleagues uncovered a paradox. Companies that had an advantage in tackling one dimension of distance were actually disadvantaged — because of the same characteristic — in another dimension.

How, exactly, did this paradox work? Larger firms, with access to more resources, can “experiment with new strategies, new products, and new markets,” the researchers wrote. This large size makes geographic distance less of a concern, but it comes with a ponderous burden of its own. Company culture is directly influenced by the country of origin, Zhang wrote. Transferring that culture into a completely different environment can cause the kind of shock that could lead to failure, even with financial and physical resources to ease the geographical distance. Conversely, smaller firms may be more nimble and able to adapt to needed cultural changes — but lack the resources to make true inroads in a foreign market.

A similar paradox exists for older and younger firms, Zhang wrote. A younger firm is more likely to adapt to a culturally distant country than an older firm might, even if that youth means that geographical distance is a greater logistical challenge.

State-owned firms face a similar paradox, one that comes down to the balance of resources against cultural flexibility. A company with state-generated resources may be better equipped to move a caravan people, machinery and materials to a distant new location. However, state-owned companies often typically lack the internal cultural flexibility to handle expansion to a different environment.

What does this mean for the average manager? Simply that going global demands meticulous weighing of factors. Does your firm have the practical resources to expand overseas? Does your staff have the personal flexibility and willingness to meld company culture with that of a different milieu? It’s a truism that major overseas expansions require money and heavy lifting. Less obviously, managers of successful companies must thread a very fine needle: ensuring they have the material resources to get their business overseas physically, while confirming that company culture is light enough on its feet to thrive in day-to-day life in a new place.

Li, Zhang, and Shi (2019). “Navigating Geographic and Cultural Distances in International Expansion: The Paradoxical Roles of Firm Size, Age, and Ownership,” Strategic Management Journal.

Never Miss A Story