Letter from the Editor

“Our location allows us to do what great educational institutions do best: give our students and faculty the resources and connections they need to solve global problems for the betterment of all.”

There is just something about a college campus in the fall that ranks among my top favorite things. Even when temperatures start to cool, there is so much life in these buildings. This year it feels even more exciting to think about new beginnings when I look at the courtyard and see construction for the new building or when I call students to talk with them about how they came to choose Rice Business. Seeing our graduate students and faculty mingling on campus in classes and at Partio is always a sign that another year — and some big ideas — are moving forward, whether through classroom discussions or faculty research or new partnerships.

We have had undergrads around McNair since we launched the undergraduate major in 2021, but the graduation of our first class last May is another big step in our growth. That milestone also means our new graduates deserve a proper welcome, so here is an open letter to the undergraduate class of 2024:

Dear undergrad alumni:

Welcome to the alumni ranks! We are so happy to have you as our first class of undergrad alumni. We know you just graduated a few short months ago, but we also know you’re already out there doing some very cool work and exploring deep passions. This is your magazine — a way to keep up with what’s happening at Rice Business, but also to stay connected to your classmates as you head out into the energy space of Houston, the tech space of Silicon Valley or the consulting world and beyond.

The Class Notes section of the magazine is for you to share your successes and life milestones. We know there are plenty of digital and social spaces out there, but we also know that this section of the magazine is well-loved, allowing our tight-knit community to stay close. Tell us about your cohorts, too. We’ll be on the lookout for undergraduate stories for the magazine.

Please share your updates with us by emailing me at maureen.harmon@rice.edu. I will also share updates with Rice Magazine, the magazine for the university at large. We would love to hear from you.

A few more to-dos for your list: Keep an eye on Rice Business Wisdom (business.rice.edu/wisdom), our online ideas magazine offering actionable insights based on faculty research, and subscribe to the Rice Business podcast, “Owl Have You Know” (business.rice.edu/owl-have-you-know), for more business knowledge and alumni stories.

As you set off into the world, know that you will always have a home at Rice Business. You belong here. —Maureen

Dean

Peter Rodriguez

Chief Marketing Officer and Assistant Dean of Marketing and Communication

Kathleen Harrington Clark

Editor-in-Chief

Maureen Harmon

Magazine Contributors

Helen Huneycutt

Annie McDonald

Scott Pett

Design Director

Bill Carson Design

Marketing

Kateri Benoit

Chelsea Clark ’23

Tessa Conrad

Tricia Delone

Dawn Kinsey

Michael Okullu

Kevin Palmer

Ananya Zachariah

Contributing Writers

Adam Buchsbaum

Maureen Harmon

Scott Pett

Proofreader

Jenny West Rozelle

Contributing Photographers

Bill Carson

Jeff Fitlow

Tommy LaVergne

An Le

Annie McDonald

Contributing Illustrator

Carra Sykes

Printing

RRD Houston

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Energy, investment groups take up leases in Houston innovation hub

“As the Ion continues to attract leading companies and organizations across industries, it’s clear that our vision of creating a dynamic and collaborative environment for innovation is resonating,” commented Ken Jett, vice president of facilities and capital planning at Rice and adjunct professor at Rice Business.

Is 24/7 Trading Inevitable?

Crypto markets trade 24 hours a day, seven days a week, which has led to discussions on whether traditional financial markets will move in the same direction. Alexander Ober, a Ph.D. candidate at Rice Business, recently co-authored a paper covering the topic.

Engineering the Future through Synthetic Biology feat. Shalini Yadav ’24

Season 4, Episode 26

Shalini, a 2024 Executive MBA grad and executive director of Rice’s Synthetic Biology Institute, shares the revolutionary potential of synthetic biology and why blending science with business is key to innovation.

Owl Have You Know

Season 4, Episode 26

In this episode, we welcome Shalini Yadav, a 2024 Executive MBA graduate and visionary leader in the field of synthetic biology. With over 22 years of research experience, including a decade in leadership, Shalini has a deep expertise in synthetic biology, immuno-oncology, and therapeutics. She now serves as the Executive Director of Rice's Synthetic Biology Institute, where she spearheads cutting-edge research, fosters interdisciplinary collaboration, and drives the institute’s mission to unlock synthetic biology’s transformative potential.

Host Maya Pomroy ’22 speaks with Shalini about her inspiring journey from growing up in Allahabad, India, to leading translational cancer research at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Shalini reflects on how her early experiences with infectious diseases and her education, from New Delhi to Stony Brook University, shaped her passion for synthetic biology. She also shares her thoughts on the field’s potential to revolutionize science and the critical role of integrating business strategy into scientific innovation.

Subscribe to Owl Have You Know on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Youtube or wherever you find your favorite podcasts.

Episode Transcript

-

[00:00]Maya: Welcome to Owl Have You Know, a podcast from Rice Business. This episode is part of our Flight Path Series, where guests share their career journeys and stories of the Rice connections that got them where they are.

A devoted scientist, innovator, and leader of Rice University's Synthetic Biology Institute, our guest on Owl Have You Know is a 2024 Executive MBA graduate, devoted to driving the synthetic biology industry into the future.

Shalini Yadav's commitment and dedication to transforming healthcare took on a bolder meaning when she chose to add MBA to her list of impressive accomplishments. She talks to us about her upbringing, fascinating work in fighting disease, and her belief that every step in her journey, including those wild risks, has led her to exactly where she needs to be.

Welcome, Shalini Yadav. Thank you for taking the time to share with us your remarkable flight path and dedication to science and research over the last 22 years. You have a bachelor's degree in biology, a master's in biotechnology, a Ph.D. in cellular and molecular biology, and now an Executive MBA. So, do you have space on your wall for all of these accomplishments, Shalini?

[01:20]Shalini: First, Maya, thank you for having me on the show. Well, this is my last degree, for sure.

[01:26]Maya: The famous last words.

[01:29]Shalini: Yeah, I mean, it just happened. I mean I enjoy the process of learning and the kind of person I am, if I have a structured way of doing things, I like doing it that way. And in terms of wall, I think I can accommodate in my office.

[01:47]Maya: You just need a bigger office with bigger walls.

[01:49]Shalini: Yeah. But Texas is the right place to have that kind of office.

[01:54]Maya: That's right. You have served as an associate director of research planning and development at MD Anderson Cancer Center, leading the multidisciplinary teams in translational cancer research. That was your former position. And you are now in a role as the executive director of Rice University’s Synthetic Biology Institute, leading innovation research initiatives, fostering collaboration across disciplines, which is what you have dedicated multiple decades in doing. Congratulations on your new role.

[02:25]Shalini: Thank you.

[02:26]Maya: And I'd love to dive in and ask you specifically about the institute and the groundbreaking research happening at Rice. But first, I'm curious about what made you interested in pursuing science and what inspired you to pursue a career in biotechnology?

[02:43]Shalini: Well, I think, right from the beginning, as a child and when I was growing up, my interest was always… I was fascinated by how our body fights infections or any kind of foreign invasion. And that fascinated me, that world of microbes, bacteria, viruses, and how are we able to fight them or how are they able to outsmart us? You know, like, we do get infected. And that was like, I always wanted to be in the field of science. And I came from a, not a very big town, a small town in India, and it's called Allahabad. Its name has been changed; now, it's called Prayagraj. So, it's a very holy city. So, basically, even coming from there just to a big city, the capital of India, New Delhi, was a big step for me and my conservative family to let me go and study and do my master's in biotechnology.

The motivation was the same. I got into the program. It was a competitive program. You have to get into it through an exam. And after that, there was no looking back because so many opportunities opened up after that. I was able to come to the United States because of my education there. I landed up in Stony Brook University. And it was an amazing experience. My graduate school studies were probably one of the best parts when I came to a foreign country first time and ever traveled, actually.

[04:05]Maya: Really? So, wait a second. So, let's back up. So, your first time going to an international… you know, your international travel was coming to Stony Brook, New York?

[04:14]Shalini: Yes, it was crazy. I still remember. And as I said, I came from a very conservative and protected kind of environment. So, for me, to take that step and get my dad's support to do that was a big thing. But it was a crazy ride to Stony Brook. I still remember, you know, like, I almost passed out because I had so many vaccines before coming, and I was not well. But the driver was, really, I think, a nice guy. He dropped me at the international relations office. Then, I realized that I don't have a graduate housing and they were going to put me in an undergrad dorm or something.

[04:50]Maya: And you had nowhere to live.

[04:51]Shalini: Yes, in a foreign country. It was crazy. I was like, “Oh, my God, what will I do now?” But, you know, I did not go to the dorm because some of my friends told me, “Oh, no, no, no, don't go to the dorm. You'll get a shock.” So, but then, I got a housing. They fixed it very soon. So, I was able to manage, but it was an adventure.

[05:10]Maya: And that's where you got your Ph.D., was at Stony Brook?

[05:14]Shalini: Yes, in Stony Brook University, with a great, great mentor.

[05:17]Maya: Did you come from a family of people that were biologists and scientists? Or was this something, were you, sort of, like an anomaly in your family?

[05:28]Shalini: One of my uncles was a scientist. Basically, a scientist means a psychologist. But my dad was well-educated. They were all in government jobs in India, most of my family. So, that was the background. I was the only one who was interested in science and, like, my brothers, they're all engineers.

[05:44]Maya: You, sort of, briefly mentioned that you were curious about microbes and infection. And was there something in your childhood or in your life that made you curious? Was it like a book or something that you saw? Or, what was that catalyst for you?

[06:00]Shalini: Well, infectious diseases affect, not in United States, but if you live in a country like India, I have seen, like, in the village where my roots are, people would not really know why they are getting, like, dysentery or typhoid. And, you know, there were problems there, which I was seeing as a child growing up. And I was like, “Why there are no solutions,” or, “How does this happen? How do we fight infections?” There were no specific incidents that I can remember that made me curious. Maybe, in the school, the teachers who taught me science made me interested in this field, is all I can think of. But that was always the question that I had, when somebody would get sick, I would be like, “Oh, why did this happen? Why we are not able to get this person better? And what's going on in the body, why we're not able to fight that infection?”

[06:50]Maya: Well, how fortuitous was that? Because now, we have you in this field and really, sort of, changing the field. I was reading about some incredible things that you did. Part of your postdoctoral work at the Rockefeller University led to the discovery of a host cell restriction factor for HIV. And I am not a scientist, but it's the MX2. So, you got your Ph.D. at Stony Brook, and then what?

[07:17]Shalini: Then, I started looking for places where I can do this kind of work, to understand, what is natural defense mechanisms? And I was restricted to New York at that time due to my family. So, I was like, “Okay, I will look in and around New York.” And one of the labs that I was interested in was a retrovirology lab, and I loved the projects that I would be doing, so I decided to go for studying HIV.

And I also, at that time, I was also not sure whether I will be in the U.S. or go back. And HIV looked like an area which would help me. If I ever decided to go back, I wanted to be in a field where I'm studying some infectious diseases or viruses. So, that was a good option. And I took it up, and it was really a great time and fun things that I did at that time was awesome, because being in a good lab with a good PI makes a lot of difference. And I was, at that time, using robots to do things because my project needed that kind of work, was awesome because you have to learn how to use it, how to program it, and how to scale down your work actually to that small scale.

So, it was a lot of fun. And believe it or not, that's why I really like… this thing attracted me because a lot of things that I did in my Ph.D., as well as postdoc, this is the future that is emerging. That attracted me to this position, actually, because I have the background to understand why it's going, where it's going, and what can happen next.

[08:48]Maya: Tell me about this MX2 host cell. I'm very, very curious about that, because like I said, I don't have a background in science as much as my whole family wishes that I did, but I don't. So, tell me about this.

[09:00]Shalini: So, basically, MX2 is a protein, right? It's a protein. And it is found in human cells, mostly, cells which are in the body and they help in fighting infections. They are called macrophages. That's one of the main cell types which expresses this protein. And the way it works is that, what we discovered, we screened the entire repertoire of genes which can be involved in restriction factors and then discovered this factor. But basically, it's a protein which will prevent HIV from entering the nucleus. So, it stops the life cycle of the virus. So, you can imagine that, if you understand how it works, you can design ways to… new drugs to basically prevent infection with HIV.

[09:48]Maya: That's fascinating that you were able to discover this. And you went on then to Weill Cornell Medical College and started doing prostate cancer research. Tell me about the jump into that.

[10:02]Shalini: I had my kids. And New York, as you know, is quite an expensive city to live, and, at that time, I, with me and my husband and the kids and the wait line for getting decent daycare. I had to take some time off, just to manage that time, and my visa status didn't allow me to go part time. So, at that time, I stopped for six months. And then, when I wanted to start again, I could have gone back, but I also, serendipitously, like, I met this surgeon and I moved into translational research because I was always interested in new technologies or innovation.

And in this case, my thought process was that I was getting to do single cell genomics in a setting which I thought is also very relevant for HIV research if you wanted to use it in a country like India or other places. So, I thought this looks like a perfect setup where I get to build this setup in Weill Cornell, going to Cold Spring Harbor with a very big group of, who are experts in single nucleus sequencing. Dr. Mike Bigler, I thought, okay, let's do this and see how it goes.

And that changed my perspective completely because I was just a basic biologist interested in how this thing works, to, “Oh, my God, there's so many problems which patients are facing.” And we, as basic biologists, what can we do to bridge this gap between clinical and translational research and basic research? And can we find solutions? Because when you bring…what I have learned in my career so far, when you bring diverse expertise together, the solutions that come out have way more value and are more impactful than what you can achieve alone.

So, bridging this gap was not something that I was looking for, but I serendipitously got into a position where I just did what was needed. That gave me a very different perspective of what scientific research can achieve, in terms of, if you understand the problems, which actually people are facing, then your solutions can be tailored, or you can design proposals to address those problems.

And that's exactly what I did over there — took a problem in prostate cancer and tried to see if we can develop better diagnostic tools to diagnose prostate cancer or differentiate aggressive form of prostate cancer from an indolent form of prostate cancer.

[12:29]Maya: And you recognized the importance of teams and the structure of teams and how that's really integral to moving forward and to making these sorts of discoveries. It's that diverse perspective, sort of, like a silver bullet, so to speak.

[12:44]Shalini: Yes, exactly. Before that, I was collaborating right from my PhD, I would say, because the lab, I was working, all my projects were in collaboration with Dr. Vendilem, who's a well-known synthetic biologist. And we were working together at that time. But the basic tenet of seeing how a clinical setup versus basic biologists versus computational scientists or radiologists and pathologists, what can we do collectively together to solve a patient-specific-centric problem was something that was… that just happened to me, to understand that, that way it can be done.

And I also got a chance to build certain things. And I realized I enjoy doing that. So, that was something that I didn't know I can do and I will like it, but I loved it, you know, from scratch, if I had to build things and that was a lot of fun.

[13:39]Maya: Well, you were stretching yourself, which seems to be the thread throughout your entire life, is that you just keep on stretching yourself. “I don't know how to do it, but I'm going to figure it out. Like, I don't have anywhere to live, but I'm going to figure it out.” And that's really an important piece of character, literally, coming from India for the first time to a completely foreign place and just doing what you got to do.

[14:03]Shalini: If thrown into a situation, I'll just figure it out.

[14:06]Maya: Right. Sink or swim, and you're not going to sink.

[14:09]Shalini: Yes.

[14:11]Maya: So, what brought you to Houston? Was it MD Anderson that brought you to Houston?

[14:14]Shalini: Yes, believe it or not, getting a chance to work with Dr. Jim Allison is an opportunity. I'm grateful to him and the opportunity that I got, again, because you're moving to a field, which is immunology, like, your body's immune system and how you can develop therapies that can help you fight cancer, in this case. I was naturally inclined in that direction. So, then, I got an opportunity. Again, grateful to the PCF Young Investigator Award that I got, that I got this network of people that I met. And through that, I was able to connect with Dr. Allison. And it, again, serendipitously, it happened that he, looking at my expertise and things that I had done, he said, “Would you like to do this work, which is a lot of scientific management and administrative?” Again, I thought, okay, as long as…I found it interesting and exciting, because again, I was handling multiple stakeholders and trying to work with multiple pharmaceutical companies, different departments, different kinds of experts, working together with all of them to handle a scientific problem, which will help, actually, to learn something new, either in understanding the disease etiology or actually bringing first in human compounds to help cancer patients who do not have any other options.

So, that was very satisfying to do that. It just happened that it was too good. Learning from Dr. Allison's group and their team, it was an amazing experience because it broadened my perspective of many, many different things. So, it was a very good experience. And I think it helped me grow in terms of how I would manage different things.

[15:58]Maya: You mentioned Dr. Jim Allison. It was an award that you won. Was that how you made the connection or…

[16:06]Shalini: Again, like in my Executive MBA, I realized how important networking is. I was not networking a lot when I moved here because I was so focused on my work. When I was in Mount Sinai, I had written a proposal and I had done the Young…Prostate Cancer Foundation's Young Investigator Award for doing prostate cancer research that I was talking about, like, how to differentiate indolent versus aggressive prostate cancer.

And there, the other young investigators that I met, through them, I got connected here. So, those connections brought me here.

[16:38]Maya: So, you were at MD Anderson for how many years before you decided, “You know what? I think I need to go get my MBA?”

[16:44]Shalini: I was in MD Anderson for six years, but it took me time to make this decision. I wouldn't lie. I wanted to do an MBA for a long time. I think I knew I will do an MBA, but I waited because my kids were smaller and I wanted them to be at a stage when I'm ready. And then, in my work, also, I wanted to feel that, is this the direction I want to go? Because there were always two paths—you can go into scientific administration management, seeing the big picture and implementing that strategically, or you could do research and go back. So, for me, I was at the crossroads. Like, after COVID, you know, COVID changed a lot of things. And for me, it made me decide which direction I wanted to take.

[17:28]Maya: That was a time that I think a lot of people were very introspective, people were on the fence. I think that COVID really solidified some folks’ decisions of what's important, what do I want to do? Why do I want to do it? And yes, I'm going to do this now.

[17:44]Shalini: Yeah, for me, that was the phase, because even though I'm very fortunate that I got a chance to work, even in the COVID phase, we were in lockdown, but just, the question that came from the leadership was, how will we study? How is COVID impacting cancer patients? Nothing existed again, right?

[18:01]Maya: Right.

[18:01]Shalini: Because how will you do that? How will you protect your employees who will work with these? First, can we collect these samples? How will we collect these blood samples? And no infrastructure existed. And what will we do with it later? And how will we convince the employees and, also, in terms of regulatory bodies, how will we convince them? And again, because I've worked with viruses before, even though we didn't know anything about COVID at that time, how will we inactivate it, think about it, and then, give papers or other studies to support what we are doing will work?

And it was a bad time, but it was a good time, in a sense, because I got involved in building all these infrastructures to do that. And it has opened up many new projects, right? Because once you have a collection of samples, new questions arise, and then new fields of studies have started in that area.

So, it was very satisfying to see that, but it was also a time to think about… I started thinking about policies and other things like, how can we influence something which will benefit the whole society? And how can you be the changemaker? And for me, to reach there, I felt I needed an MBA. And I went and talked to Jim and I said that I want to do this MBA. And he supported me. He said, “Sure, you should do this, if you think that's what you want to do and it'll make you happy.”

[19:22]Maya: Nobody tried to talk you out of it?

[19:25]Shalini: My brother did. My younger brother was like, “You're crazy. You already have a Ph.D., you don't need an MBA.” But he's in India, but we always had this relationship. We are pulling each other's legs. So, he's like, “Okay, now, you're the crazy scientist going on a crazy rant of doing this.” But I was really passionate. I'm very grateful that, you know, my kids, my family, my husband, everybody supported me. And my workplace also supported the efforts. And I made amazing, amazing community here in Rice with the EMBA group that I had. It was an amazing experience.

[20:00]Maya: Let's talk about that amazing experience because we're both EMBAs and you actually started the year that I graduated. So, I was done in 2022, and you started in 2022. Once you decided, because you said you always… this is something that you always knew you wanted to do. So, when you decided to apply, tell me about that process. How old were your children at this time? Because you said that a lot of it, a lot of it does have to do with the support of your professional network, your personal network, your family, your friends, because it is. It's a leap.

[20:31]Shalini: Yeah. My daughter was 10, and my son was, at that time, 13. They were very supportive. I remember in the beginning, I remember like my seniors would say, “Survive till Halloween, you'll be fine.” I remember going home and I’d say, “I'm going quit, I can't do this.” And those two were like, “You can do it. Definitely, you can do it, mama. And mama, you have to do this.” And, you know, so I was like, “Okay.”

So, I had a very big support system in my family to do that. That was their age, and they were ready to let me explore this. And good things came out of it. Like, my daughter became very independent, which I actually do not like now.

[21:18]Maya: Absolutely, independence is a good thing all around. If your kids are independent, I mean, that's what you want. You want them to be able to fly without you. So, tell me about your time at Rice and about the experience that you had. What was the most fulfilling for you?

[21:33]Shalini: Rice’s Executive MBA was really life-changing for me. I really think that my perspective about almost everything changed. The biggest impact has been two. The one is, I've understood the importance of having discovered myself as a leader, what are my value systems, which I have to hold to work, to do anything, anything in life. And that clarity came through interactions with my cohort, through interactions with my peers, and some of my professors. Like, the amount of time they gave me and some classes that I did really made me think and made me find that footing of where I am and how I will move forward.

So, that clarity was very important. And second is that I always have worked in collaborative environments and teams, but having the broad perspective from diverse fields and to be able to work with all the different areas, my horizon of the way I think, see things, and visualize things. I was always a visual person. I think I'm a futurist, in a way.

[22:47]Maya: I like that. Futurist, I like it. That's one of the great joys, is that you get different flavors of people. You have Full-Time MBAs, you have Professional MBAs, you've got Online MBAs, you've got Executive MBAs, and everybody has such a unique and diverse perspective of where they are.

And what's interesting is that, you know, you started your journey at Rice, and now, you've transitioned into a phenomenal opportunity and have broadened your career by being a part of Rice. So, tell me about how that transition has been from being in, you know, the medical field to now being in academia.

[23:29]Shalini: It was a very organic transition. I don’t… like, I was in a very academic setting of basic research, moved into translational. It was not that I was specifically looking to move into this direction. It's just that this particular position attracted me so much, because working in the medical center and seeing all the problems that people were trying to solve, research problems, scientific questions we are trying to ask, I also realized that a point comes when innovations will happen in an academic setting, you know. Like, you reach a point you can do up to a certain extent, not because you're not capable, it's more got to do with what is your focus or priority, right?

As a clinician, your priority has to take care of your patients, and then you have a research group or support system. But the focus is always different, right? But to understand the depth of the biology and the problems that you're trying to solve, you need to have a different kind of passion. And I felt that passion and I know that. So, I know that major innovations that we need in the next 10 years or 20 years in medicine or other fields, whether it's, like, our whole society I'm talking about, whether it's a bio-economy, bio-manufacturing space.

All these things are very strong in Houston and all of them are waiting for breakthroughs. In my mind, those breakthroughs come in an academic research setting. And Rice is the place to do it, especially in synthetic biology. So, that was my attraction towards the position. And my background, serendipitously, it happened that my Ph.D. work was also doing something synthetic with older tools. At that time, it was not a field, established name field, but work was very similar. And it's a small world. Right now, I'm working with people probably where I was collaborating with those synthetic biologists for my Ph.D. And now, the lab people are Dr. Caleb Bashor is an assistant professor here and we are working together.

[25:32]Maya: So, a full circle.

[25:34]Shalini: A full circle, yes. And it's just amazing to just know that, you know, it's such a small world, to come back full circle and see how the field has grown and having the vision where we can take it. So, together with Caroline, who is the scientific director for the institute, all three of us talk a lot about it and how we'll move forward and how this will grow. And my main drive was that innovation attracts me, and I'm a builder by my DNA profile, I think. So, this was a perfect fit that way. And I'm always, like, being in a space where you are really doing breakthroughs. I felt stagnancy where I was before, and that's why I started my MBA, actually. And now, with the tool sets that I have to apply in a completely different setup, is really exciting.

[26:22]Maya: And fulfilling.

[26:23]Shalini: Very, very fulfilling, yes. Yeah, true. That's the reason. I'm passionate about what I do, and I'm really enjoying it right now. To be in an area to see what can be done and what the potential impact can be, if we are able to pull this off correctly.

[26:41]Maya: So, let's talk about synthetic biology because it's being heralded as the next scientific revolution. Can you talk about synthetic biology and its applications and the things that you're doing at Rice?

[26:54]Shalini: Sure. It is a field which brings together biology and engineering. Basically, you are using engineering principles to redesign biology. In a simple term, I would say, you are working with DNA to design solutions for the biggest challenges that are facing the world in different ways, using DNA as the material to do different things.

The simplest example, which I wish I can show you, but think of DNA as the building blocks in a Lego. And then, you can design it, build it, rebuild it into anything that is good for society and you want to do it and you want to make it. Anything, a beautiful picture, a beautiful… anything that will impact the world in a positive way, whether it is agriculture, biomanufacturing, or, obviously, medicine.

[27:48]Maya: Can you share some of the most exciting research that's happening right now?

[27:53]Shalini: There are many. First, I'll give you an example, which is probably one of the first ones, which is not from Rice, but it is important to understand that, probably, one of the first in bioproduct was artemisinin, which is, like, an anti-malarial drug, which is derived from plants. It used to depend on crops, right? Like, if the weather is bad and you do not have the harvest, you won't have enough to supply the world, and it's a major problem. Malaria is a major problem. Scientists were able to take the entire pathway for making artemisinin and transfer it into yeast. Like, you brew, right? Like, yeast you make bread. They were able to do that and make artemisinin, which can basically solve that problem of dependence on crops.

So, that's one of the examples. There was a McKinsey report a couple of years ago, I think, where they talked about, like, around 400 products, which probably are products of synthetic biology, not synthetic biology, per se, but products which are at a stage that can be commercialized and the potential impact in terms of dollars would be $4 trillion, probably.

It has a huge potential for commercialization as well, the products at this stage. I'm only talking about the products. One example is a drug, Sitagliptin, for diabetes. It is a synthetic biology-based product. It is a very successful drug, probably, ninth most prescribed drug.

[29:16]Maya: Is it for type 1 or type 2?

[29:18]Shalini: Type 2.

[29:19]Maya: Which is a lot more prevalent than type 1, if I'm not mistaken.

[29:21]Shalini: Yes. But in as far as Rice is concerned, we are very uniquely positioned because we have both a very strong microbial setup. Whereas, we have the world's best scientists working in this field. And then we also have the eukaryotic system where you have T-cell therapies and others. And we have scientists in that area as well. It's a great group of brilliant, brilliant scientists.

And an example I can give you is, one of the work that is going to come out is, you know, antibiotic resistance is a huge problem. It is going to grow in the next 10 years, where, probably, the number of people that will die of antibiotic resistance globally would probably increase more than 10 million. And there are no novel therapies.

[30:09]Maya: Do people know this? I mean, other than you, because you're in the field, but do people understand this?

[30:15]Shalini: Well, you can go to World Health Organization and other websites and you will be able to see these stats. But I am personally passionate about these things. So, I like… in my spare time, I like reading about these things, if that's geeky, I don't know, but, you know, I…

[30:32]Maya: It's okay to be geeky. I'm pretty geeky myself.

[30:35]Shalini: Yeah. So, it matters. And there are not a lot of novel solutions or therapies. Professor James Chappell, Joff Silberg, and Vicky Yao, and we are bringing a computational biologist and bioengineering and biosciences people together. Two are biosciences. So, they have come together and are trying to build RNA-based… like, the COVID vaccine was an mRNA vaccine… RNA-based antibiotics, which will be personalized. Like, right now, you take an antibiotic, it clears out of all your bugs in the body—good, bad.

[31:06]Maya: Even the good ones, yes. That’s why you have to eat yogurt to make sure that your stomach has all of those, yes, yes.

[31:12]Shalini: So, now, they have come up with an idea where they're going to use this engineering principle and synthetic biology to make targeted antibiotics, RNA-based.

[31:21]Maya: Fascinating.

[31:22]Shalini: Yeah. So, it will just kill the bad bacteria and spare others, if it works. And it's an amazing collaboration, and I'm proud to say that Synthetic Biology Institute at least initiated. We are all about building new collaborations, and this is one of the collaborations where we have given seed funds to start expanding this work.

[31:43]Maya: So, in order for all of these incredible innovations to make it to the marketplace, you really need to have a base in business and to understand all of the different components — the financials and the accounting and the marketing of it and the culture of the environment that you're in. So, having an opportunity to have the brilliant scientific background that you have, and also, the business expertise and prowess, it's really a very important and integral combination of the two.

So, I think there's lots of people out there that are brilliant scientists that, sort of, shy away from pursuing an MBA or, you know, being later on in their career and going for an executive MBA. So, what would you say to those that are listening, that are scientists, that, maybe, hadn't contemplated this yet? What would you say to them about jumping in and doing something like what you did?

[32:43]Shalini: I would like to say that scientists, in general, are passionate about what they do. And your perspective changes after MBA. I never had this perspective. The way I understand things now are completely different than I would have done two years back.

[32:57]Maya: 100%.

[32:58]Shalini: Basically, understanding the business aspect of things, because ultimately, even if you're making technologies, the biggest use of that technology will come if it is reaching people and helping. And if you do not have that perspective and you have the passion to do something which will have impact for the community in a way, right? So, if community matters to you and if you're bothered by things around you, which you want to change, and you think with this you cannot, I think taking that leap where you will learn things, which I think, basically, as a scientist, or in our training as graduate students or even medical studies, we are taught to be very focused. So, having to come out of that shell and embrace this bigger picture and having the strength to think about what impact I can have, because if you understand both sides of it, what you can think of achieving, you won't get it if you are just on one side of things.

So, for me, I like getting trained. That's why I thought of doing an MBA at that time. But I think, the amount of impact that you can have around you, it will broaden your horizon. To make yourself a better person, people around you better, and create a world which will be a better place. And in order for you to get there, I feel that doing a program like that requires just the first step.

[34:28]Maya: Yes.

[34:29]Shalini: We are all very trained to be hard workers, so that's not a problem. It's just taking that leap and believing that there is a bigger purpose to it. And that bigger purpose comes from understanding how it will impact what is happening around the world. And in your community in Houston, that matters to me because I feel that, what I stand for, Rice is here, but we are surrounded by very strong ecosystems or communities, like, whether it's Texas Medical Center, whether it's biomanufacturing, whether it's TMC Innovation or even Space Center, I think all of these can be leveraged and we can build a community to become a global leader or global hub for this, that's what is possible. And you can see that if you've done an MBA. That's what I'm trying to say. Before that, you can see one part, but now you can see, oh, my God, this is the impact that it will have if we are aligned and working together.

Yeah, I wanted to stand corrected that I have the figure right now for antibiotic resistance. I think, by 2050, the number of deaths would be 10 million.

[35:38]Maya: Wow.

[35:39]Shalini: So, that's huge. So, see, imagine the depth of problem I'm talking about in this case. And I can give you another example. Caroline is… like, kids get excited. We had a high school outreach, community outreach. So, some high school students came to our institute and they did lab work to get exposed to synthetic biology. They'd never even heard of the term. So, for them, it was awesome. But, like, one of the students that I saw the presentation, he worked in Dr. Caroline Ajo-Franklin's lab, where he was able to grow bugs or bacteria in a flask and then was able to generate electricity or light a bulb, LED bulb. Like, my kids do the experiment, right? Potatoes or lemon, you put two wires. And here, he was so excited to see that, you know, he can use bacteria, grow them, harvest those electrons and generate it at a small scale. But imagine the scope if we have the infrastructure where it can go.

[36:34]Maya: Lots of work to do, but so much optimism.

[36:37]Shalini: Exactly. It’s an exciting time to be in this field and to connect with like-minded people here and then move across boundaries.

[36:46]Maya: Yes. So, what's next for you? I know you, this is a new step, a new opportunity, but looking out 10 years, what do you hope to achieve?

[36:58]Shalini: Right now, the only focus I have is that, how can we become the hub, the place to be for synthetic biology? And I think the amount of time it will take is the time that you are talking about. Five to 10 years, I think that's the amount of time it'll need, if it really goes, as I think it will, or I plan to, means to become a hub, not only, like, if somebody says, “Okay, I want to do something in the synthetic world.” “Hey, Rice is the place. You should go there,” you know, or, you know, “Houston is the place.” The number of opportunities, the number of industries and academia-industry partnerships that can happen in the future.

So, for me, right now, my focus for the next five to six years is that. And if that succeeds, I don't know. I just know that it'll be something. Right now, my focus is just, will I get there?

[37:50]Maya: Something tells me you will. Well, it'll be great to catch up in a few years and see the progress. It's really been a pleasure. I learned so much in the short time that we had together. And thank you, Shalini, for taking the time to catch us up with what's going on in your world. We look forward to many more exciting developments and breakthroughs coming from Rice.

Thanks for listening. This has been Owl Have You Know, a production of Rice Business. You can find more information about our guests, hosts, and announcements on our website, business.rice.edu. Please subscribe and leave a rating wherever you find your favorite podcasts. We'd love to hear what you think. The hosts of Owl Have You Know are myself, Maya Pomroy, and Scott Gale.

You May Also Like

AI Is Providing a Fresh Perspective to Everyday Problems

ChatGPT enhances creativity and problem-solving in ways that traditional search tools can’t match.

Based on research by Jaeyeon (Jae) Chung (Rice Business) and Byung Cheol Lee (University of Houston)

Key findings:

- A recent study finds ChatGPT-generated ideas are deemed an average of 15% more creative than traditional methods.

- ChatGPT enhances “incremental,” but not “radical,” innovation.

- ChatGPT boosts creativity in tasks normally associated with human traits, like empathy-based challenges.

We all know ChatGPT has forever changed how we do business. It’s modified how we access information, compose content and analyze data. It’s revolutionized the future of work and education. And it has transformed the way we interact with technology.

Now, thanks to a recent paper by Jaeyeon (Jae) Chung (Rice Business), we also know it’s making us better problem solvers.

According to the study published in Nature Human Behavior by Chung and Byung Cheol Lee (University of Houston), ChatGPT enhances our problem-solving abilities, especially with everyday challenges. Whether coming up with gifts for your teenage niece or pondering what to do with an old tennis racquet, ChatGPT has a unique ability to generate creative ideas.

“Creative problem-solving often requires connecting different concepts in a cohesive way,” Chung says. “ChatGPT excels at this because it pulls from a vast range of data, enabling it to generate new combinations of ideas.”

Can ChatGPT Really Make Us More Creative?

Chung and Lee sought to answer a central question: Can ChatGPT help people think more creatively than traditional search engines? To answer this, they conducted five experiments.

Each experiment asked participants to generate ideas for solving challenges, such as how to repurpose household items. Depending on the experiment, participants were divided into one of two or three groups: one that used ChatGPT; one that used conventional web search tools (e.g., Google); and one that used no external tool at all. The resulting ideas were evaluated by both laypeople and business experts based on two critical aspects of creativity: originality and appropriateness (i.e., practicality).

In one standout experiment, participants were asked to come up with an idea for a dining table that doesn’t exist on the market. The ChatGPT group came up with suggestions like a “rotating table,” a “floating table” and even “a table that adjusts its height based on the dining experience.” According to both judges and experts, the ChatGPT group consistently delivered the most creative solutions.

On average, across all experiments, ideas generated with ChatGPT were rated 15% more creative than those produced by traditional methods. This was true even when tasks were specifically designed to require empathy or involved multiple constraints — tasks we typically assume humans might be better at performing.

However, Chung and Lee also found a caveat: While ChatGPT excels at generating ideas that are “incrementally” new — i.e., building on existing concepts — it struggles to produce “radically” new ideas that break from established patterns. “ChatGPT is an incredible tool for tweaking and improving existing ideas, but when it comes to disruptive innovation, humans still hold the upper hand,” Chung notes.

Charting the Next Steps in AI and Creativity

Chung and Lee’s paper opens the door to many exciting avenues for future study. For example, researchers could explore whether ChatGPT’s creative abilities extend to more complex, high-stakes problem-solving environments. Could AI be harnessed to develop groundbreaking solutions in fields like medicine, engineering or social policy? Understanding the nuances of the collaboration between humans and AI could shape the future of education, work and even (as many people fear) art.

For professionals in creative fields like product design or marketing, the study holds especially significant implications. The ability to rapidly generate fresh ideas can be a game-changer in industries where staying ahead of trends is vital.

For now, take a second before you throw out that old tennis racquet. Ask ChatGPT for inspiration — you’ll be surprised at how many ideas it comes up with, and how quickly.

Lee and Chung, (2024). “An Empirical Investigation of the Impact of ChatGPT on Creativity,” Nature Human Behavior.

Never Miss A Story

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

Houston's Rice University tops new 2025 list of best colleges in Texas

The most prestigious higher education institution in Houston has done it again: Rice University has topped WalletHub's 2025 list of the best colleges and universities in Texas for 2025.

Staff Spotlight: Adrian Trömel

Rice Business alum and current Lecturer in Entrepreneurship discusses working at Rice University and living in Houston.

Assistant Vice President for Strategy and Investments, Lecturer in Entrepreneurship

Q: How long have you worked at Rice?

A: I’ve been at Rice full time since July 2023. I’m fortunate that I’ve been able to return “inside the hedges” since earning my master’s degree at the Jones Graduate School of Business in 2018 and am now a lecturer in entrepreneurship since 2021.

Q: What is your favorite part about working for the university?

A: The people and the process — I am lucky enough to work alongside and for passionate individuals who are solving some of the world’s most pressing problems. At Rice, we generate new knowledge through research and disseminate that new knowledge through publication, teaching and commercialization. Being part of the process and supporting our students and faculty is what brings me in every day.

Q: What do you want people to know about living in Houston?

A: Houston is one of the most diverse cities in the U.S — we resettle more refugees than any city in the Americas. With that diversity not only comes a world-class culinary scene, but from diversity of background comes diversity of thought, talent and innovation.

Q: What do you do in your downtime?

A: You’ll find me in my free time spending time with my wife and son, often cooking for them, and if weather and time allow, free diving and practicing yoga.

Q: What’s your favorite spot on campus to show someone?

A: A walk around the inner loop to show the oak-lined paths has to be capped by a stop at Valhalla.

Q: What’s the most exciting time of year for you as it relates to Rice?

A: Around April/May students and faculty are wrapping up projects, and we start to see the forms of new potential startups take shape at events like the Rice Business Plan Competition and Napier Rice Launch Challenge. This goes hand in hand with the run up to graduation as some of those new graduates get ready to become entrepreneurs.

Q: What’s the one thing that makes Rice special to you?

A: The tightness of the community — once an Owl, always an Owl! I have met Rice alumni on both sides of the Atlantic in bars and restaurants, at conferences and cafes and in all situations. The “parliament” supports their own.

Q: If you could be Sammy The Owl for a day, what would you do?

A: Only a day?! If just for a day, I’d go to the international arrivals terminal at IAH and greet those coming in from overseas. Who doesn’t love a giant owl?

Q: How would you describe your experience as a Rice employee?

A: Mission-driven every day. I know why I show up and that permeates what we do in Rice Innovation.

Q: Where do you see Rice in 25 years?

A: Rice will continue to be a leading research and teaching institution, defined by global partnerships and outstanding innovation. Rice-developed technologies will underlie some of the biggest changes to fundamental industries, generating energy, redesigning networks and saving lives amongst others.

Q: Describe Rice in four words or less.

A: Innovative, collaborative, driven.

Q: What else have we not talked about yet that merits discussion?

A: So much! From Rice’s role in Houston to our role in global efforts such as the energy transition, contributions in every layer of the value chain in artificial intelligence to supporting global diversity and equality across social, environmental, health and economic resources … those are just some of the things that come to mind.

You May Also Like

Rice University’s Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business today announced the launch of its Graduate Certificate in Healthcare Management program, a 10-month, credit-bearing professional credential designed for current and aspiring leaders seeking deep expertise in the business of healthcare.

7 Student Internship Journeys Toward Success

Summer internships are a perfect opportunity to put theory into practice, particularly for our Full-Time MBA students.

Summer internships are a perfect opportunity to put theory into practice, particularly for our Full-Time MBA students. Internships can help guide career changers, and they frequently serve as a gateway to full-time positions after graduation.

From creating AI implementation strategies in California to transitioning into new industries, our students prove that there’s no challenge too big. Here’s a look at how seven of our Full-Time MBA students are shaking things up.

#1 – New Beginnings at BCG

Name: Alphy Thomas, Full-Time MBA ’25

Title: Summer Management Consultant

Company: Boston Consulting Group (BCG)

Location: Houston, TX

When Alphy began applying for internships, she had one goal: launch her consulting career. BCG presented an opportunity for her to do that and more. Over the summer, she helped her client achieve savings using financial analysis skills from her MBA courses. Now, she feels more confident in her problem-solving skills and has gained a new community of lifelong mentors. Alphy encourages prospective MBA students to “take full advantage of your MBA Program, nurture both hard and soft skills, and learn from your mistakes.”

#2 – AI Strategies at F5

Name: Parool Didwania, Full-Time MBA ’25

Title: Technical Program Manager Intern

Company: F5

Location: San Jose, CA

Parool struck gold on LinkedIn where she landed a role with F5, an American tech company that specializes in app security. As a technical program manager intern, she spent her summer working on an AI implementation strategy that focused on employee efficiency, standardization and automation, which she presented to the company’s CPO. “It's okay to feel uncertain at times,” says Parool. “The key is to bounce back, learn from the experience and work even harder.”

Interested in Rice Business?

#3 – Global Consulting at Kearney

Name: Diana Carrillo Romero, Full-Time MBA ’25

Title: Associate Consultant

Company: Kearney

Location: Dallas, TX

This summer, Diana sharpened her skills as a strategy consultant at Kearney, where she assisted a global consumer packaged goods (CPG) client with network optimization using key concepts from her finance and operations management courses. The most memorable part of her internship was developing strategic solutions and measuring growth alongside industry experts. Her advice for prospective students? “Be curious, keep your options open and never underestimate the power of good communication skills.”

#4 – Driving Strategies at Toyota

Name: Cyrus Mistry, Full-Time MBA ’25

Title: Product Planning and Strategy Intern

Company: Toyota North America

Location: Plano, TX

With a background in automotive engineering, Cyrus took his love for cars to Toyota’s product planning and strategy team. During his internship, he conducted competitor analyses and developed strategies to prolong the lifespan of Toyota products. Following the Japanese concept of genchi genbutsu, which means “go and see it,” Cyrus obtained valuable insights into customer needs by off-roading in trucks and SUVs and visiting RV dealerships. Prospective MBAs should “keep an open mind and embrace unexpected opportunities,” he says, “but above all — enjoy the journey, because time passes quickly!”

#5 – Landing Deals at Lionstone

Name: Sam Stephens, Full-Time MBA ’25

Title: Acquisitions Intern

Company: Lionstone Investments

Location: Houston, TX

With no prior experience in real estate or finance, Sam embraced the challenge of working in acquisitions at Lionstone Investments. Crediting much of his expertise to Professor James Weston, Sam sharpened his practical skills by working on real estate investment projects, underwriting deals and engaging with real-life business problems. He advises prospective students to step outside of their comfort zone by networking in new industries and asking questions confidently.

#6 – Scouting Solutions at ScottMadden, Inc.

Name: Gustavo Biato Oliveira, Full-Time MBA ’25

Title: Consultant

Company: ScottMadden, Inc.

Location: Atlanta, GA

Gustavo took his international experience to ScottMadden, Inc., where he engaged in client meetings, organized workshops and collaborated with teams across the company. Passionate about the trends and geopolitics of the energy transition, Gustavo now specializes in energy and serves as an ambassador for the Career Development Office (CDO). “Embrace diverse experiences, cast a wide net and stay persistent,” he says.

#7 – Pivoting with Humana

Name: Delphine Ariguzo, Full-Time MBA ’25

Title: Procurement Intern

Company: Humana

Location: Remote

Delphine, a former accountant, spent her summer as a procurement intern at Humana after connecting with the team at the Consortium Conference. Hoping to build a career in healthcare, Delphine used this experience to gain a clearer perspective on industry trends and challenges while spearheading a successful procurement optimization project to improve supply chain efficiency. Her advice for career changers? Embrace new opportunities, leverage your skills and don’t be afraid to pivot.

You May Also Like

Keep Exploring

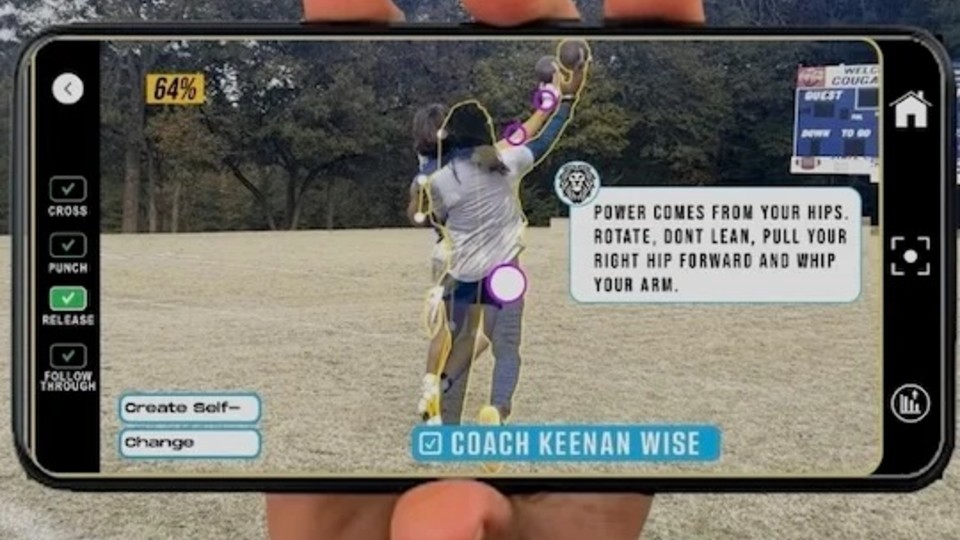

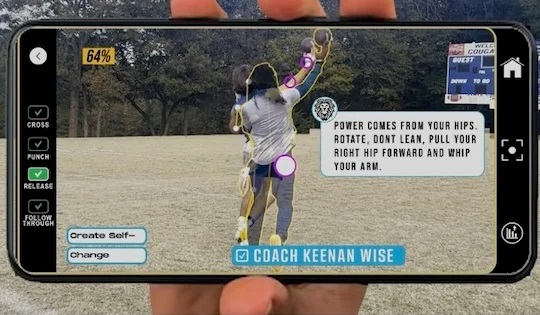

Rice partners with BeONE Sports to transform athlete performance with AI technology

Rice University’s Office of Innovation and Rice Athletics have formed a strategic partnership with BeOne Sports, a startup co-founded by Rice MBA alumni Scott Deans and Jason Bell alongside former Rice student-athlete James McNaney.

Alumni-founded startup aims to enhance athlete care, injury prevention and performance optimization

Rice University’s Office of Innovation and Rice Athletics have formed a strategic partnership with BeONE Sports, an innovative startup founded by Rice alumni that is pioneering advanced sports performance technology. This collaboration aims to elevate Rice’s status as a national leader in athletic achievement and research-driven innovation, positioning the university as a testing ground for state-of-the-art, holistic care technologies for student-athletes.

By integrating BeONE Sports’ mobile motion-capture AI and advanced data analytics with Rice’s premier sports medicine and rehabilitation programs, the partnership sets a new standard for athlete care, injury prevention and performance optimization.

“This partnership aligns perfectly with Rice University’s mission to harness innovation for the betterment of our community,” Rice President Reginald DesRoches said. “By integrating cutting-edge technology from BeONE Sports with our already world-class athletic and academic programs, we are providing our student-athletes with the tools they need to excel both on the field and in life. This collaboration is a testament to Rice’s commitment to leading through innovation and offering unparalleled opportunities for our students.”

Game-changer: AI-enhanced sports performance

BeONE Sports is recognized for its groundbreaking AI-based “Comparative Training” technology, which digitizes and analyzes elite athletes’ biomechanics using just a mobile device. With a comprehensive global database of human movement integrated into the platform, Rice athletes will gain access to high-level performance comparisons and data-driven insights. This collaboration will enhance Rice’s capabilities in athlete monitoring, rehabilitation and injury prevention, said Tommy McClelland, vice president and director of athletics.

“At Rice Athletics, we are always striving to be at the forefront of innovation, and our partnership with BeONE Sports exemplifies that commitment,” McClelland said. “By leveraging their state-of-the-art AI technology and data analytics, we can elevate how we support and develop our athletes — ensuring they are healthier, stronger and better prepared to succeed both athletically and academically. We’re excited about how this collaboration will position Rice as a leader in athlete care and performance.”

Born from Rice, built for the future

BeONE Sports was co-founded by Rice MBA alumni Scott Deans and Jason Bell alongside former Rice student-athlete James McNaney. Emerging from Rice’s prestigious Jones Graduate School of Business’ entrepreneurial track, the company focuses on utilizing AI computer vision technology to enhance athletic performance, provide exposure and offer elite-level training. By making its technology accessible through mobile platforms, BeONE Sports aims to democratize access to sports training, providing advanced resources to a wider audience.

“BeONE Sports was born from the collaborative environment at Rice, where business leaders and engineers work together to solve real-world problems” said Deans, CEO of BeONE Sports. “We’re thrilled to continue that journey with Rice Athletics as we build the world’s first human recognition models specifically designed for sports performance and beyond. Our mission is to provide cutting-edge technology to maximize potential in the simplest, fastest and most versatile ways possible. This partnership with Rice is an exciting step toward democratizing access to sports technology for athletes and coaches at all levels.”

Rice’s commitment to innovation

Rice is committed to pushing the boundaries of innovation, where cutting-edge technology and world-class education intersect to create meaningful impacts across various fields. The partnership with BeONE Sports exemplifies this vision, enhancing the university’s athletic and academic offerings while reinforcing Rice’s dedication to fostering an ecosystem where transformative ideas can thrive, said Paul Cherukuri, Rice’s chief innovation officer and vice president for innovation.

“BeONE Sports exemplifies the innovative spirit we champion at Rice, where entrepreneurship and engineering excellence converge,” Cherukuri said. “As a startup founded by former Rice MBA students and athletes in collaboration with our computer science engineers, BeONE reflects Rice’s dedication to cultivating talent and driving transformative change. This partnership showcases how our innovation ecosystem is expanding beyond business into athletics, creating new opportunities that benefit both our students and the world at large.”

Beyond advanced performance tools and analytics, the partnership will also create academic and professional development opportunities for Rice students and faculty. Initiatives will include internships, research projects and collaborations on innovative ventures, offering a “living portfolio” approach that provides hands-on experience in sports technology. This prepares students for careers at the intersection of science, athletics and technology.

You May Also Like

Rice University’s Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Business today announced the launch of its Graduate Certificate in Healthcare Management program, a 10-month, credit-bearing professional credential designed for current and aspiring leaders seeking deep expertise in the business of healthcare.

Consulting for a Sustainable Future: Gustavo Biato Oliveira’s Summer Internship at ScottMadden

Discover how Gustavo Biato Oliveira’s Summer Internship at ScottMadden aligned perfectly with his career aspirations.

PREVIOUS CAREER AND CURRENT INTERNSHIP

Previous position before MBA:

- Title: Planning and Performance Manager

- Company: Petrobras

- Location: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Summer Internship:

- Title: Summer Consultant

- Company: ScottMadden Inc.

- Location: Atlanta, GA

HOW DID YOU SECURE YOUR INTERNSHIP?

I secured my internship through a combination of five coffee chats with employees and two interviews (one with HR and another with a partner). Fortunately, I had people who referred me to other employees, eventually connecting me with a director who facilitated the interview process.

WHAT WERE YOUR RESPONSIBILITIES DURING THE INTERNSHIP?

As a summer consultant, my responsibilities involve collaborating with the project team to enhance our project’s processes and policies within the organization. Specifically, I engage in client meetings, assist in organizing workshops, create materials and propose ideas to drive value through cultural change.

WHAT DEPARTMENT WAS YOUR INTERNSHIP WITH?

My internship is with the Corporate Shared Services Solutions department.

HOW DID YOUR MBA COURSEWORK PREPARE YOU FOR THIS INTERNSHIP?

My MBA coursework, particularly the core curriculum at Rice, has been instrumental in preparing me for this internship. Courses in Finance and Financial Accounting have equipped me to handle the financial aspects of the project. Additionally, Business Communication classes have been essential for effective interactions with consultants, partners and client representatives.

HOW DOES THE INTERNSHIP ALIGN WITH YOUR CAREER GOALS?

Joining a consulting company with a strong history in the energy industry aligns perfectly with my career aspirations. Outside of my project, I also have the opportunity to engage in discussions related to energy topics. Currently, I’m involved in the energy transition group, which supports my career goals and was a key factor in choosing to pursue my MBA at Rice.

HOW DO YOU THINK THE INTERNSHIP WILL HELP YOU WITH YOUR MBA STUDIES OR FUTURE CAREER?

This internship provides valuable insights into the consulting world and helps me assess my fit within the industry. It’s an excellent opportunity to explore my career switch before applying for full-time positions. Upon returning to Rice, I plan to continue my personal and intellectual growth by specializing in energy. I’m eager to delve into topics like geopolitics of energy, energy transition trends and energy policies. Additionally, I’ll serve as an ambassador for the Career Development Office (CDO) and Recruiting and Admissions. Lastly, I look forward to participating in the Leader as Coach program at Rice to further develop my leadership and coaching skills.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE PART OF YOUR INTERNSHIP EXPERIENCE?

My favorite part of my internship experience is the opportunity to return to the workforce after nearly a year as a full-time student. The sense of reward is immense. I appreciate the positive work environment and the camaraderie within my team. Additionally, my family and I are enjoying our summer in Atlanta — a city we’ve never explored before. We’re immersing ourselves in the local history and culture of Georgia. Being here has allowed me to experience life at the Atlanta office firsthand, engaging in various activities. For instance, we participated in a volunteer day project with Atlanta Beltline, as ScottMadden is a community partner for that initiative. Furthermore, I’ve had the chance to connect with families visiting the office and engage in numerous in-person interactions, which has deepened my understanding of the firm’s culture — an aspect I truly love!

WHAT ADVICE DO YOU HAVE FOR PROSPECTIVE STUDENTS?

Embrace the diverse experiences available during your MBA journey beyond academics. Explore various topics, join clubs and participate in events. When it comes to recruiting, cast a wide net and maintain faith in the process. While coffee chats and information sessions require energy, they are worthwhile. Take your time to understand companies and alumni, envision yourself working there and stay persistent.

Gustavo Biato Oliveira is a Full-Time MBA student in the Class of 2025.