Law Of The Jungle

How Short Sellers Keep The Market Healthy

Based on research by Alan Crane, Kevin Crotty, Patricia Naranjo and Sebastien Michenaud

How Short Sellers Keep The Market Healthy

- Short sellers are often maligned in the stock market.

- Some claim short sellers artificially push down stock prices, sabotaging firms.

- But short sellers may actually help the market by revealing when a stock is overpriced.

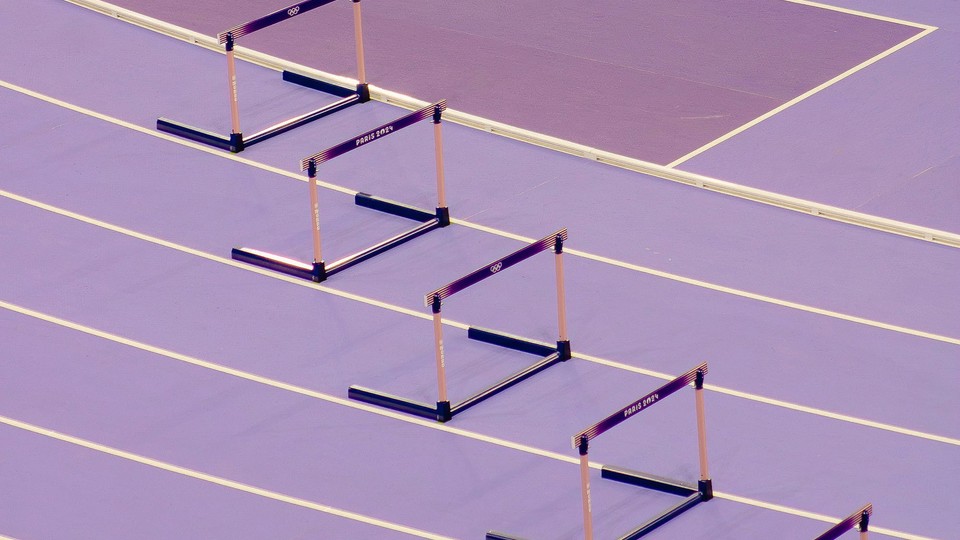

Hike into any environment where different species coexist. Whether it's the jungle or the U.S. stock market, the large beasts and investors tend to receive the most admiration and attention. The burrowers, the foragers, the critters that dig and sting are mostly seen as pests. This is definitely the case with those least-glamorous investors: short sellers.

But in most ecosystems, all the participants serve a useful function. And in a recent paper, Rice Business professors Alan D. Crane, Kevin Crotty and Patricia Naranjo and former Rice Business professor Sebastien Michenaud show that it’s time to revisit the popular view of short sellers. These often-maligned market players "borrow" shares from brokers in order to sell them and then rebuy them — ideally at a lower price. According to their many critics, short sellers are guilty of artificially pushing down prices, intentionally sabotaging firms’ reputations in order to turn a profit.

Using an innovative research technique, the Rice Business scholars showed that this stereotype is false. Not only do short sellers not distort stock prices, banning them has no impact on the market. In fact, the researchers say, there is ample evidence that short sellers can offer a valuable service.

These findings give a new look at a species of investor vilified for centuries. Suspicion of short sellers has existed at least since the 17th century in Amsterdam, where an early version of today's Wall Street trading took place on a city bridge. These concerns have intensified during financial crises: Governments banned short sales in Britain during the 1700s after the collapse of South Sea investment mania, in the U.S. in the 1930s after Britain abandoned the gold standard and during the 2008 global financial crisis.

As the SEC explained in the last instance, "Recent market conditions have made us concerned that short selling in the securities of a wider range of financial institutions may be causing sudden and excessive fluctuations of the prices of such securities ... so as to threaten fair and orderly markets."

The reality is that the effects of short selling have been hard to pin down. A 1977 study argued that short-sale bans support stock prices by blocking short sellers' overly gloomy projections and encouraging the more optimistic prices accepted by other buyers. A 2003 study, on the other hand, argued that banning short sellers could actually cause market crashes by keeping legitimate bad news out of the pricing process.

One problem is that the variables in real-life markets are almost impossible to isolate. The Rice researchers found an ingenious solution: They headed to Hong Kong, where a distinctive policy allowed them to compare the prices of almost identical companies, some eligible for short sales and some not.

Each quarter, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange bans short sales for companies that fall within a particular set of criteria, including size and turnover. For many firms that fall just to one side or the other of these thresholds the difference is mostly due to chance. By comparing firms just inside and just outside the thresholds, the Rice Business researchers were able to show that banning short sales had no impact at all on stock prices.

Critics of short sellers are right about one thing, though: These industrious but unpopular buyers really do play a role in the market. But it's a good one.

"Our results show that short sellers are not driving prices down," Crane explains. "Yes, these guys are showing up when things are bad. But they are not the cause. Other research shows that some are very diligent about reading fundamental research. They show up when things are not going well. They uncover fraud."

These services can make a difference for mainstream investors. If a stock is overpriced, for example, investors can be hurt by buying it. When a short seller digs deeply into a company and finds a $100 stock is only worth $80 that overpricing is exposed, and the price may tumble like a rotten tree.

Like any ecosystem, in other words, the stock market is a complex and subtle place. Tempting as it may be to value only the elegant and the impressive, it turns out that the unpopular, the unaesthetic — and even the pesky — can play an important role too.

Alan D. Crane is an associate professors of finance at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Kevin Crotty is an associate professors of finance at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Patricia Naranjo is a former assistant professor of accounting at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

To learn more, please see: Crane, A. D., Crotty, K., Michenaud, S., & Naranjo, P. (2019). The causal effects of short-selling bans: Evidence from eligibility thresholds. Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 9(1), 137-170.

Never Miss A Story