Pop Culture

Why There's Still Potential In Products That Have Lost Their Fizz

Why There's Still Potential In Products That Have Lost Their Fizz

James Quincey, head of the Coca-Cola Co., was being grilled about Diet Coke.

The chief executive of the world’s largest soda company – its market capitalization is about $188 billion – was on an earnings call with analysts anxious to know what he was doing to save the iconic brand. Quincey had been talking up his massive firm’s bright future in its wide range of products, but then a question came up about plans to revive Diet Coke, sales of which had been in decline for years, losing out to non-soda competitors such as LaCroix and San Pellegrino.

“What’s the picture of success?” an analyst asked. Would the new plan just stanch the bleeding? Or could the legendary brand actually grow again?

Panic about Diet Coke’s fate has weighed on Coca-Cola’s stock price and given birth to hundreds of articles about the company’s “flat” earnings. But the truth is there’s opportunity in decline. In fact, some companies manage to increase profits even as sales drop. It’s a concept so counter to typical business thinking that the phenomenon is often overlooked.

“If your industry is shrinking, it’s tempting to spend money to get new customers,” says Rice Business marketing professor Amit Pazgal, who has studied increasing profits in declining markets. “But that can be expensive. It’s much better to spend on the customers you have left.”

Those faithful few can prove lucrative. Pazgal points to the cigarette industry as a powerful example. Its companies found ways to raise prices on their most loyal — and yes, addicted — consumers even as demand declined. When states started slapping new sin taxes on cigarettes, the tobacco companies added a little more to the price. Their least loyal, and likely most price-sensitive, customers had already quit the habit. That meant the companies were left with their best customers, many of them willing to pay more.

Not all declines, however, are ripe for reaping increased profits. According to Pazgal, demand needs to trail off. It can’t just plummet. The customer base needs a substantial number of loyalists who will stick with the brand through hard times. That way a business can steadily increase prices to the right consumers, even if there are fewer of them.

Diet Coke, as it turns out, has plenty of loyalists — people who turn down a Diet Pepsi at a restaurant or get grumpy when their home supply of Diet Coke runs low. One of the most famous Diet Coke fans is President Donald Trump, who reportedly downs 12 cans a day. People magazine has written about the drink’s “strangely dedicated fan base,” and the motto “My favorite color is Diet Coke,” has made its way onto T-shirts.

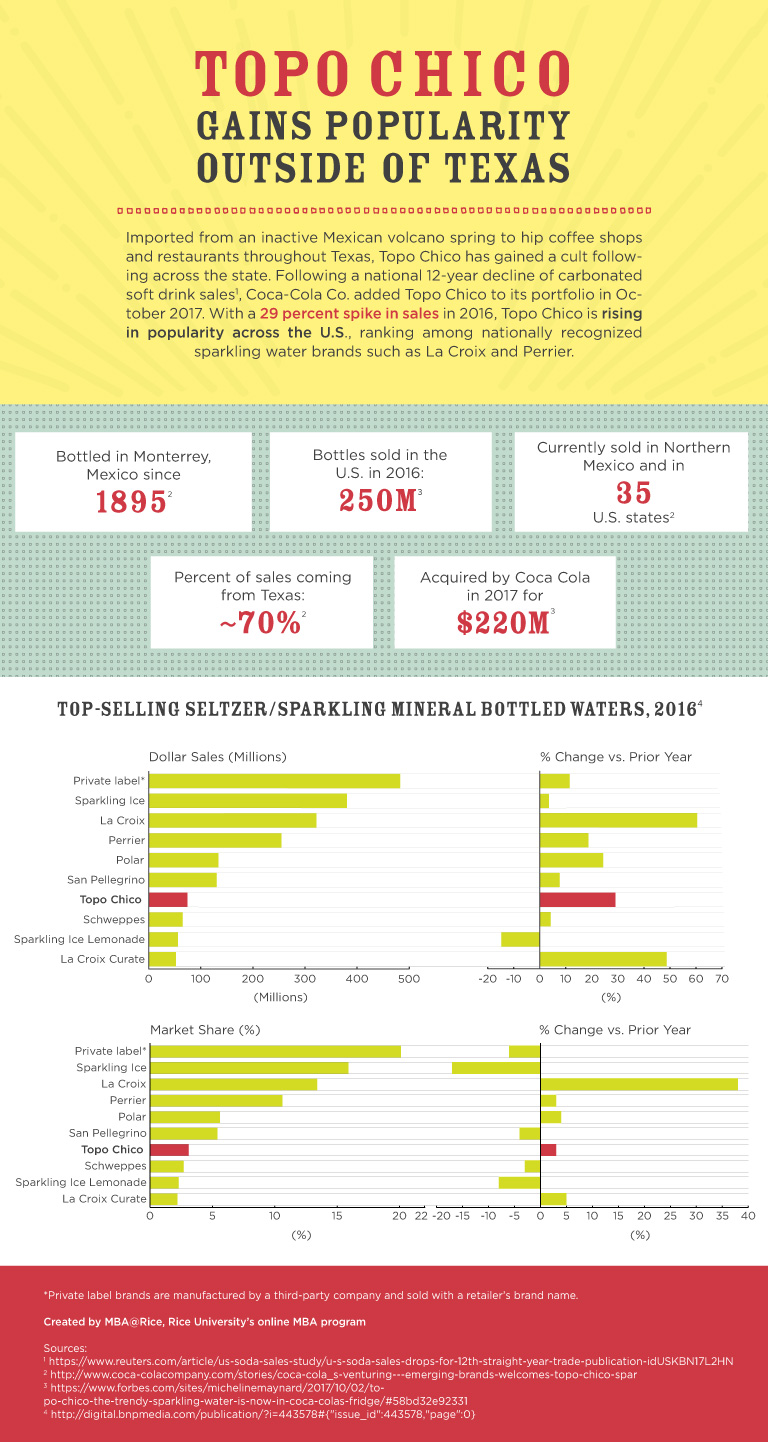

Such loyalists have helped keep Diet Coke one of the best-selling brands in the nation, even as soda consumption has fallen to its lowest level in three decades, and sales of calorie-free and unsweetened fizzy waters have doubled. Coca-Cola is clearly adapting to customer preferences by diversifying its portfolio with product acquisitions like the trending sparkling water brand Topo Chico.

In his call with analysts, Coca-Cola boss Quincey sounded enthusiastic about the potential of new Diet Coke flavors. The descriptive names — twisted mango, feisty cherry, zesty blood orange — were a clear bid to lure younger buyers. Yet the new offerings could also misfire with core Diet Coke drinkers who love their soda just as it is.

Understanding what keeps people hooked is key, says Christian Goy, cofounder and managing director of Behaviorial Science Lab in Austin, Texas, which provides companies such as Coca-Cola insights into customers’ priorities.

“For loyal customers, what we can see and measure is how expectations are fulfilled and why,” Goy says. “What we’ve found is that sometimes a product fulfills one or two expectations very well. That’s the hook the company needs to play up to continue to be paramount in their minds.”

A declining market can be freeing for a company. It doesn’t have to pander to consumers who aren’t connected to the brand, the kind who will switch allegiances at the drop of a coupon. That’s one reason, research shows, that knockoffs of high-end luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton handbags are not necessarily harmful to a company: The fakes weed out consumers who are most motivated by price.

Few companies, though, have the discipline to keep from chasing those price-sensitive buyers. That helps put downward pressure on prices, but it also means forgoing profits from loyal customers who wouldn’t mind paying a little bit more for a luxury handbag.

Pazgal suspects the same is true for Diet Coke. While most businesses shudder at the prospect of managing a product’s long decline, Pazgal suggests, the journey itself can prove a worthy ride.

“Think before you leave,” he says. “Because it might still be profitable for another 20 years."

Citation for this content: MBA@Rice, Rice University’s online MBA program.

Never Miss A Story