Railroad Ties

Remembering Ed Williams, The Person Who Laid Down The Tracks Of Entrepreneurship At Rice Business

By Weezie Mackey

Remembering Ed Williams, The Person Who Laid Down The Tracks Of Entrepreneurship At Rice Business

In remembering the life and legacy of Professor of Entrepreneurship (Emeritus) Ed Williams (1945-2018) we are republishing an article from the Spring 2015 edition of the Jones Journal in his honor.

Ed Williams grew up in Houston and discovered early on that he had a knack for selling

At age seven he started putting old magazines in the back of his wagon and knocking on doors. “Half the people would slam the door in my face. The other half would listen. A few would buy used magazines. I’d make another round in another neighborhood, ‘do you have any old magazines you’d like to get rid of?’ My cost of goods sold was zero,” he said, revealing the first inklings of an audaciously entrepreneurial childhood.

Williams’ father worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad. When he was old enough, he took school excursions to Austin or San Antonio once a year. “My dad would lend me $5. I’d buy curios on the trip and then go through the train on the way home selling them to kids or trading. I’d come home with at least $25. One time I had some extra inventory, and I went to see Carl Cohen who owned the little grocery store around the corner from where I lived at 14th and Studewood. He liked me. I asked Carl, would it be all right if I sold some of these things outside his store? He said yes, so I set up my little stand and sold out the first day. I was 10.”

From a little red wagon to crossing the border into Juarez to buy exotic inventory — Mexican bats and bull whips — Williams built a business and an entrepreneurial acumen one sales trip at a time. Today, at 70, always ready with a story, it isn’t hard to imagine the blond-headed kid with the gift of gab who readily admits he had better luck selling to women than men. There would be no holding him back.

Mentors made the difference

As of July 1, 2014, Ed Williams — formerly the Henry Gardiner Symonds Professor of Management — retired from his career teaching entrepreneurship at the Jones School. He estimated that he taught about 3000 students in 100 courses in 36 years, including the first graduating class — all together more than half the alumni. It’s no wonder so many of them have stories to share. And that Williams has even more.

Somehow, the war stories of entrepreneurship stick. Whether it was born from necessity or desire, his entrepreneurial approach shaped him as a scholar and an educator.

“I knew from a fairly early age that I was going to be looking after myself by the time I was 17 if not sooner,” Williams said. “My dad was a yard master with SP. He was out in the field originally but became a freight re-check clerk, examining mileage and commodity records. He was born in 1897, lived through both World Wars and the Depression. My dad was very conservative. You don’t live through two wars and a depression and come out a risk taker. His own history had a lot to do with mine because the people who worked for the railroad never made a lot of money, at least not at his level. It was sufficient to live on but not to pay for college.”

Through hard work, pluck and several formative relationships during his life, starting with store-owner Cohen, Williams made his way in the world. And then some.

As a student at the newly built Waltrip High School, he became a little less entrepreneurial and a little more studious. After a few summers as an archives clerk at the Magnet Cove Barium Corporation, he landed a plum summer job through his aunt at University State Bank, working as a sight payer and bookkeeper. “The man who owned the bank was a fellow named Goldston. He asked me what I was going to do with my life?” Williams explained that he was saving to go to college. Goldston invited him, after work and on his own time, to come up to his office and learn to read the Wall Street Journal. “We started on page one. While he was teaching me how to read the Wall Street Journal and the quotations and prices,” Williams said, “he was also teaching me how his bank operates. It was fascinating.”

During his senior year of high school, while president of the student council, Williams was introduced to Bob Waltrip, the owner of Heights Funeral Home. A lifelong friendship began that day as Waltrip shared his plans for Service Corporation International (SCI), where Williams would become vice president years later. First, of course, the budding business man had to go to college. He studied economics and finance at Wharton at the University of Pennsylvania. “I got through Wharton in three years because I ran out of money,” Williams said. After graduation, when Waltrip asked him if he was ready to come work, Williams said, “No. I like academia. He told me he thought I was making a serious mistake.”

The fast train

After looking into and deciding against graduate school at Yale — it was longer and more expensive than what he could afford — Williams got a hold of the head of the finance department at the University of Texas. “The tuition was $50 a semester for all the courses you could take. There were no constraints on time. You had to pass five field exams and write a dissertation. And you had to take so many course hours. I signed on and finished my Ph.D. in two years. I was 22.”

He shrugs and claims it was a matter of necessity. “I had no money. I got the Texas Savings and Loan League fellowship and ultimately wrote my dissertation on the savings and loan industry. I remember one semester I was taking seven courses. I was teaching two and writing my dissertation. And living on a $100 a month.”

As he was finishing his doctorate, Williams attended the American Economic Association meeting and ran into a former professor of macroeconomics from Wharton, Paul Davidson, another mentor who remains a good friend to this day. “I was looking for a job. He was a professor at Rutgers by then. He said, ‘You’d be younger than the kids in our graduate school, but why don’t you come up and give a paper, and we’ll see how it goes.’ It went well.” He was hired as an assistant professor of economics in the College of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers. After two years he was hired as an associate professor of finance in the Faculty of Management at McGill University.

Three years later he called Bob Waltrip. SCI had gone public in 1969 and was doing very well. He told Waltrip he was ready to leave academia for a while. “I went down to visit and got a job offer to be a vice president. It was three times what I was making at McGill plus stock options. This was 1973. My basic job was to oversee our investments, including our endowment care funds and still am today as chairman of the investment committee of our board of directors. In those days, we had $9 million. Now we’ve got $9 billion.”

Today, SCI is the world's largest operator of funeral homes and cemeteries in North America, and Williams worked there five years before he got a call from the first dean of the Jones School, Dr. Robert Sterling, asking if he might be interested in returning to academia.

“I said to Sterling, if I come back to academia, I’m not interested in teaching finance and economics. I did that already. I want to do something different.” Which is how Williams arrived at Rice as the founder of a new program in the emerging area of entrepreneurship. It was 1978, and Williams was 33.

Head of the class

Only a handful of business schools were teaching entrepreneurship back then. “The exciting thing about that time was the Jones School was new,” said Williams. “The upshot of that was you could mold it.” Molding it meant finding literature and textbooks, creating a curriculum. “There was a textbook being used, Patrick Lyle’s The New Enterprise. He was an adjunct at Harvard. It was a case book, but it had snippets of the theory of entrepreneurship. Which is almost an oxymoron. I spent the summer with that book preparing to teach the fall class, The New Enterprise. The spring class would be Buying and Selling Companies.”

Williams loved being back in the classroom. “I like talking to people and explaining things. It’s funny because even when I was in junior high I would pretend to be a teacher. I would stand up with a little black board and teach Texas history or something like that. I pretended that I had students. I even graded fake papers.” He laughed. “I’d write stuff up with mistakes in it and grade it. I always wanted to be a teacher.”

The second year he added a third class. “My agreement with Bob Sterling was I could teach two the first year and three the second. The added class was micro-economics, which I didn’t really want to teach, but I did, and I met my wife Sue in that class. She was a student,” he smiled. “But nothing happened until later.” Susan ‘84 had two children, Laura and David ‘99, and a dog from a previous marriage. The two married in 1983 and now have five grandchildren.

In 1979, Williams attended the first Babson College Entrepreneurship Conference to see what other business schools were doing. Rice was in good company. Harvard, UCLA, USC, Carnegie Mellon, Wharton and Babson were the universities that pioneered the development of this new discipline, and they were all in attendance. Next, Williams began to recruit the first of many adjunct faculty members who were instrumental in the early success of the program. The first was George Ballas, inventor of the Weed-Eater, who team taught the New Enterprise course with Williams.

The question remained: can you teach someone to be an entrepreneur? “My thinking on that is it’s a practice. You learn to be an entrepreneur by having done it for a while. You can structure an analysis of it, almost like a social scientist looks at a phenomenon. Actually teaching somebody to be an entrepreneur is a different story. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be put in a formal framework and examined.”

Enter Al Napier

When Al Napier began teaching Information Technology at the Jones School in 1984 there were still only 15 full-time faculty members. Williams had known Napier as a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin in the ’60s. They struck up their old friendship and began fishing together. On one of their trips, they talked about Napier joining the entrepreneurship faculty. “He had his computer consulting company, Napier and Judd, but we were getting to the point where the classes were getting larger and larger. I wanted help teaching The New Enterprise. It kind of brightened my day because needing another professor showed the entrepreneurship program was working.”

It brightened Napier’s day as well. “Ed has been a great friend. He mentored thousands of students and alumni with their entrepreneurial pursuits and mentored me in my teaching of entrepreneurship,” Napier said. “His impact has been immeasurable.”

Being bigger gave the Jones School the opportunity to claim some fame in the world. “Businessweek came down here,” Williams said modestly. “They nominated a few people back in ’96 for top entrepreneurship professors, and I was No. 2.” In the country. Not only that, but he won so many teaching awards within the school, that he eventually declined to be in the running so that others could take home the honors.

The rest is history. After Napier accepted the position, and The New Enterprise course ultimately became his, more adjuncts were hired, including Jerry Finger, a successful banking and real estate entrepreneur, and Dennis Murphree, a serial entrepreneur who was also a savvy venture capitalist.

From one faculty member teaching two courses in 1978, the program now has over 23 faculty members teaching 27 entrepreneurship-related courses. The year 2013 marked the naming of the Ralph S. O’Connor Associate Professor in Entrepreneurship, awarded to Yael Hochberg, and a schoolwide entrepreneurship initiative, for which she is executive and academic director.

Go out and learn a business

Williams walked among a sea of students in the Rice Memorial Center, looking professorial. He came from a course in statistics and investments that he was teaching with John Dobelman. “It’s through the statistics department. He’s the professor in charge, and I go over and lecture some. Once a week, three hours. Gives me a chance to stay in touch with students. I like the lecturing. I do it for free. I do it for me.”

Though the two just wrote a text book together — Investing for Profit: A Data Based Approach — the teaching of entrepreneurship never seems far from his heart. “I used to try and leave the students at the end of the year with this advice: go out and learn a business. Know that business. Then buy one in that area. Jack Ledford did that. Even though he’s military and has a financial background. He actually got his feet wet in the operations of a business.”

Ledford, class of ’02 and CEO of Spearhead Services, added, “Ed’s class really opened my eyes to a whole world I didn’t know existed. I realized that’s what I needed to do. He taught us it’s about the balance sheet not the income statement. Managing the balance sheet is the answer. He’s been an investor in two of my companies. A lot of people don’t put their money where their mouth is. He does.”

Cooper Etheridge, class of ’03 and president of Automation Technology Inc., agreed. “He was the very first person to invest in my business, proving that he is willing to practice what he teaches. Ed represented a breaking away from the usual and mostly theoretical approach of our other classes. He emboldened his students, and made us feel, while we were in school, that we were already in the game and to start acting like it.”

Williams scowls at what he sees as his own limitations. “It’s still not sufficient. A student could take my class. They know all the tricks of buying and selling but they still don’t necessarily know how to operate a business. Buying and Selling is easier, but it’s still not a substitute for knowing how to run something.”

Sometimes he had a student with some kind of experience. Take Caroline Caskey Goodner ’92, CEO of Caskey Holdings LLC, as an example. “Her father is a physician. He’s also quite an inventor and entrepreneur. Her mother is as well. She grew up in an environment of ‘let’s start a business. Let’s do this.’ And, believe it or not, that helps.”

Goodner said, “Ed’s class and his enthusiasm for entrepreneurship was the catalyst for me starting a company after graduation. I had no intention of pursuing entrepreneurship when I entered business school, but after catching his passion for being an independent employer and employee, I decided to start the company I had devised in a business plan during his class.”

And business plans are vital. But it is Williams’ belief that while the skillset of being an entrepreneur is teachable, “Being one is not.”

On the horizon

Rob Royall ’84, a partner at Ernst & Young, said Williams offered this advice in one of his classes: the key to success and building wealth is to find something no one else wants to do and become very good at it. “When I pursued an expertise in derivatives accounting, there was literally one person in all of Ernst & Young who was deeply experienced in it. I eventually became his successor and the leader in the firm on the topic—the topic no one else was clamoring to cover. They made me a partner in order to get coverage on the topic and the risk it presented to our practice.”

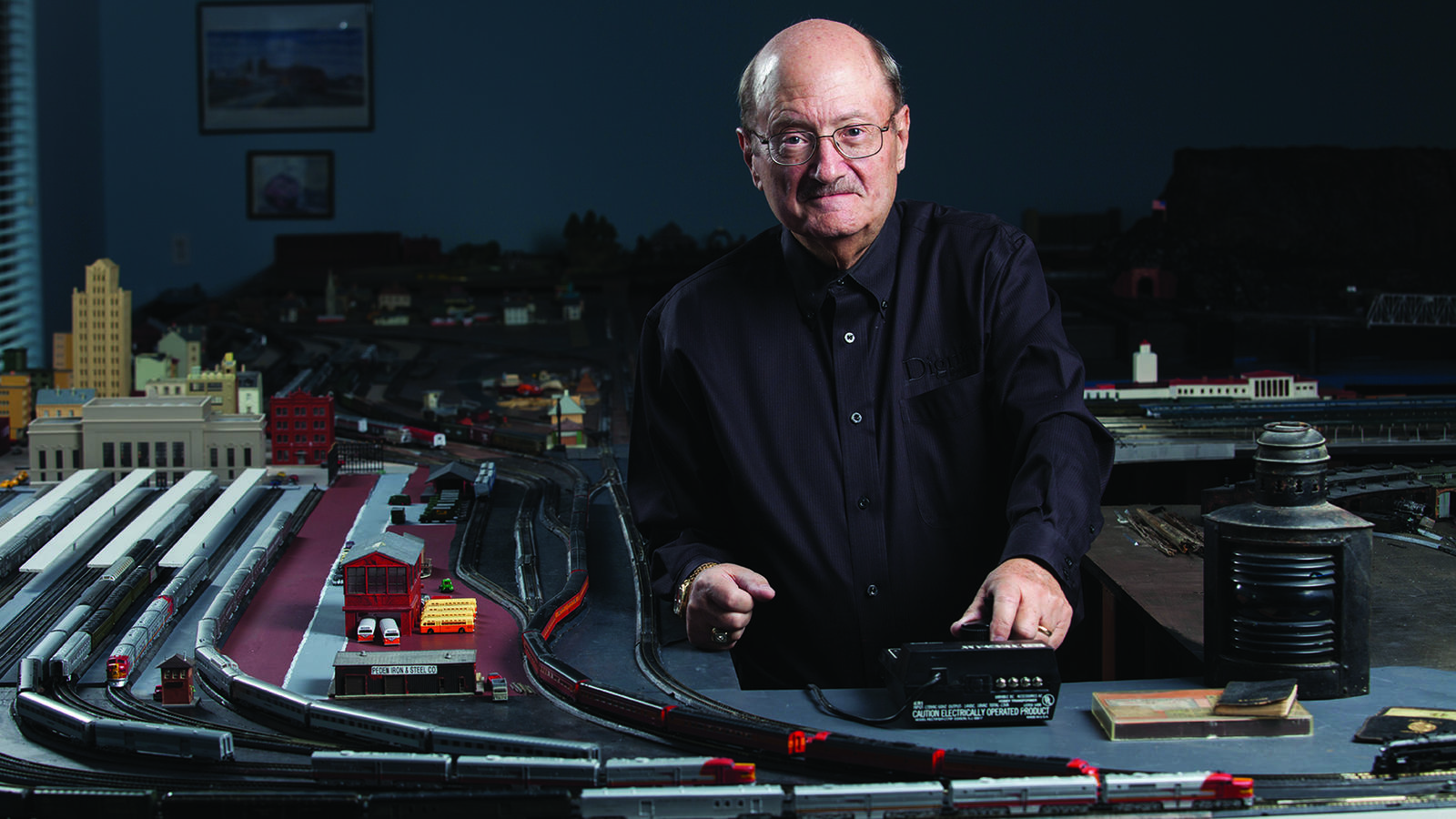

That kind of advice and the practical foundation he provided has made the entrepreneurship program what it is today. It is the legacy he leaves in his wake. His free time is jammed packed with golf, the investment committee at SCI and his own personal investments, teaching with Dobelman, the model railroad set that takes up 1,500 square feet and hundreds, possibly thousands, of feet of track.

The idea of the train set was to give him something to do in his 70s and 80s. “When I was a kid, we went everywhere on the train because we had a free pass. That was the way we got around. We didn’t even have a car. So I’ve always been interested in trains. Always enjoyed riding them. Even to this day I love to take a train.” The elaborate train is a replica, of sorts, of the Southern Pacific’s main line, which ran from New Orleans through Houston to El Paso and Los Angeles, Oakland and San Francisco, and then all the way to Oregon. “I started with Houston and made big passenger stations, including the two in Houston – Union Station and the SP's Grand Central Station. I now have every train the SP railroad had from that era.”

The historical precision of stations and cities from the 1950s — he’s working on Los Angeles now — requires a strategic perspective and the constant care and maintenance of a master gardener. “I like operating them. I enjoy putting them together and planning what will go where.”

From his first entrepreneurial adventures to the meticulous model railroads, Ed Williams looks much the same in retirement as he did in the first blush of his career: there’s no holding him back.

Ed Williams was a Professor of Entrepreneurship at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University. BusinessWeek named him one of the top two of the nation's best entrepreneurship teachers. He believed exposure to entrepreneurship is essential to a business education.

Weezie Mackey is the Associate Director of Marketing and Communications at the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University.

Never Miss A Story