The Snark Heard Round The World

Rudeness is contagious. How can we slow the epidemic’s spread?

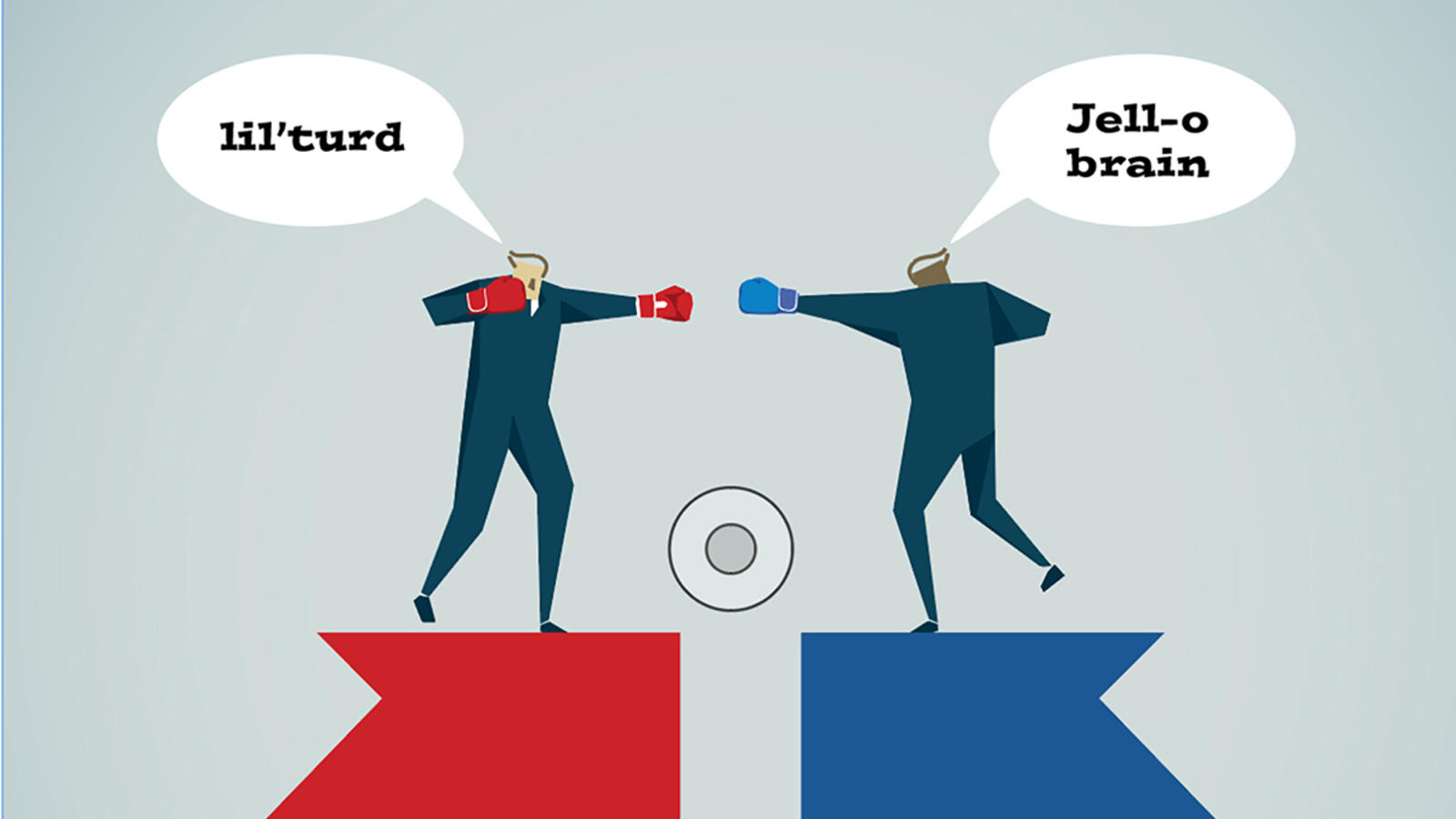

If you voiced your support for Joe Biden or Bernie Sanders on social media during the March Democratic primaries, you’d have gotten a quick lesson in how rampant name-calling has become. Bernie’s fans called Biden supporters “racist trash” and labeled the former Vice President “a guy with Jell-O for brains.” Biden boosters called Bernie bros “thugs” and “little turds.”

This internet trend crosses party lines, of course: President Donald Trump routinely tweets derogatory names for his political opponents — many of them height-based, such as “Mini Mike” Bloomberg and “Liddle’ Adam Schiff,” in which the superfluous apostrophe is apparently meant to magnify the insult.

As the dust from Super Tuesday settled, Trump used the phrase “Mini Mike” more than half a dozen times in less than 24 hours. Bloomberg, meanwhile, has called the president a “carnival barking clown.”

It’s not every day that you see the nation’s top leaders hurling playground-style epithets at each other. Except that these days, it is.

The rest of us are doing it, too, as the recent Democratic infighting reveals. Research shows that Americans have become increasingly antagonistic toward people they disagree with. Gone are the days of agreeing to disagree: When we differ with someone, we let them know — and we let them have it. Whether or not this constitutes an unprecedented crisis in civility, as some have argued, it’s clear that abusive language pervades the public discourse, much of it in the form of name-calling.

Rudeness, naturally, is nothing new. The problem is that name-calling, especially very public name-calling by very high-level figures, is contagious. A study by University of Florida researchers found that when we see other people being rude, we’re more likely to behave similarly. What’s more, it’s an automatic response that happens outside our awareness, making it difficult to consciously curb our own rudeness. We become carriers of a highly infectious agent: Each time we’re rude to someone else, we spread our vitriol to them and, potentially, to anyone in earshot.

The effects are surprisingly long-lasting, too. The University of Florida study measured the perceived rudeness of students in a series of negotiations. When one student sensed that their partner had behaved rudely, they themselves were more likely to be perceived as rude by their next partner.

“Some of the negotiations took place one after another, and some took place up to seven days apart. We found that the time between negotiations didn’t seem to matter,” writes Trevor Foulk, one of the researchers, who is now a management professor at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business. “Even if negotiations were a week apart, the rudeness experienced in the previous negotiation still caused participants to be rude in their next negotiation.”

The likelihood of contagion is even higher when the person behaving badly is in a position of power, says Marlon Mooijman, a professor of organizational behavior at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business.

“Some research has shown that abusive practices (such as bosses humiliating others and using degrading language) tend to trickle down in organizations. For instance, if the CEO treats the managers poorly, the managers tend to treat the supervisors poorly, and the supervisors treat the subordinates poorly, who in turn treat each other poorly,” Mooijman says.

Incivility on any level can lead to serious problems in the workplace, including reduced performance, creativity and retention, according to Christine Porath, a professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business. Researchers estimate that workplace rudeness, and the resulting negativity, costs organizations about $6 billion per year.

It costs us all a lot more in terms of the quality of our relationships and our own well-being. So how can we break the cycle? Luckily, kindness can also be contagious: Research shows that seeing someone behave generously or altruistically makes it more likely that we’ll behave likewise.

In a recent UCLA study, some people watched a popular Thai commercial featuring a man who helps people in his neighborhood (by giving money to a panhandler, feeding a stray dog, and helping a street vendor lift her cart, for example) while others watched a parkour video. The participants were then given $5 for their time and told they could put as much of that money as they wanted into an envelope that would go (anonymously) to charity. Those who watched the video about the helpful man gave significantly more than the parkour viewers — in fact, some of the envelopes contained more than the $5 they earned in the study.

When people in power show kindness, it can have an outsized trickle-down effect, just as unkindness does, according to Mooijman. In organizations, the entire culture can change depending on whether the CEO is respectful or rude.

“Some of my research shows that when bosses trust others, their power tends to be an asset instead of a liability, as people react more positively to being respected and trusted by those with power than those without,” he says. “This suggests that change should start at the top.”

These effects can be amplified by how much exposure we have to the actions, and the language, of our leaders. If the boss tweets a lot, we become near-constant witnesses to their courtesy or their cruelty.

Incivility has always existed, after all, but social media hasn’t — and in an increasingly connected world, rudeness spreads like lightning. But kindness can, too. Even if name-calling is unconsciously contagious, we can still make a determined effort to put down our poison pens and say something nice — or nothing at all.

Jennifer Latson is the editor of Rice Business magazine and the author of “The Boy Who Loved Too Much,” a nonfiction book about a genetic disorder that makes people incapable of unkindness.

This op-ed originally appeared in the Houston Chronicle.