Onward. Forward.

COVID radically transformed the way we live our lives — and the way we do business. Which of these changes are likely to stick around?

The COVID-19 pandemic revolutionized the way we work, shop, socialize and study — along with nearly every other aspect of our lives. And while the crisis seems to be subsiding, things may never get back to normal, or at least not the normal we knew. In the business world, remote work and video conferencing transformed workplaces; entire industries pivoted to offer virtual services and online ordering; business travel and even handshakes became unheard of. So which changes are likely to fade away, and which will become a permanent feature of our new normal? Rice Business editor Jennifer Latson asked professors to weigh in on how the pandemic is reshaping the ways we’ll do business long into the future.

Interviews have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Creativity could blossom, but managers need to keep the mindset going.

By Jing Zhou, Mary Gibbs Jones Professor of Management

The pandemic was an externally imposed shock to the system that encouraged every employee to tap into their creative potential. They may have been just going to work as a routine and now are questioning why things are done in certain ways. That prompts them to question which process is really good for the company or their work and which may be out of date or inefficient. This mindset of challenging the status quo and coming up with new and better ways of doing things is the essence of creative idea generation at work. It could lead to process improvements, as well as new product or service developments. If any company can hold onto that mindset after the pandemic, they could really benefit.

The pandemic was an externally imposed shock to the system that encouraged every employee to tap into their creative potential. They may have been just going to work as a routine and now are questioning why things are done in certain ways. That prompts them to question which process is really good for the company or their work and which may be out of date or inefficient. This mindset of challenging the status quo and coming up with new and better ways of doing things is the essence of creative idea generation at work. It could lead to process improvements, as well as new product or service developments. If any company can hold onto that mindset after the pandemic, they could really benefit.

How can managers keep it going? They really need to see themselves not just as a manager, managing their employees’ creativity, but first and foremost, start to think about themselves as a leader: How can they lead by example and engage in creativity themselves? Have they mastered the tools that facilitate creative idea generation? Second, they have to build a system that not only encourages and coaches employees on how to generate creative ideas, but also how to evaluate and implement them. Employees really need to know what happens to their ideas when they share them. Some people try really hard to come up with an idea, but they never hear anything back from management or receive feedback on how to come up with ideas that can truly add value. Or employees submit great ideas, yet managers really only want to hear ideas that would create low-level, incremental change, not truly disruptive change. Part of the solution to that is to train managers to recognize creative ideas and to provide constructive feedback. Maybe you’re not going to use the idea right now, but you need to let the employee know that it’s a valuable idea and you can hold onto it for some time in the future.

A lot of companies don’t have a system in place for encouraging creativity, and that held them back during the pandemic. Not surprisingly, their focus has just been to survive — they’ve been reacting to challenges, and next week there’s something new, so they just make decisions on the go. One company that did have a system that worked well is Memorial Hermann. They have a chief innovation officer, and they were already working to digitize healthcare before the pandemic hit. The infrastructure was already in place to make telemedicine possible, and that made it so much easier to help patients during the crisis. They had a great vision for innovation, a senior executive in charge of innovation and a core group of people in place to generate and implement creative ideas. They realized that a digital transformation was coming and they needed to be ready. In the pandemic, their innovation saved lives.

Downtown business districts will survive, but office space will look very different.

By Jefferson Duarte, Gerald D. Hines Associate Professor of Real Estate Finance

The pandemic is not going to be the death of the downtown business district. There are many CEOs that want their office workers back, so I don’t think downtowns will become ghost towns. There may be less demand for some of that office space for a while, but I think much of it will come back. But the design of office space is going to change. We believe people innovate better when they’re working together in person, so the office could become more of a hub where people enjoy going in to meet with their peers and exchange ideas. It becomes less of a place where you just go and do your work. The design of these top-tier office spaces is becoming a way to attract highly skilled employees, by making it a place where people have fun going.

We believe people innovate better when they’re working together in person, so the office could become more of a hub where people enjoy going in to meet with their peers and exchange ideas. It becomes less of a place where you just go and do your work.

These design changes can also translate to entire neighborhoods, like Houston’s new innovation district, where the Ion is opening up. There’s this idea that we want whole neighborhoods where people enjoy going to work. It’s not just about the office building but about the surrounding infrastructure. You can meet up with colleagues and maybe grab a coffee and go watch a lecture, recharge, exchange ideas, create something new, and then you might go back home to do the actual work. But this gets to the idea that innovation happens when people from different backgrounds meet, and that creates a different real estate need. Real estate design has a big role in creating these moments where people meet and talk and new ideas are created. That’s a trend that’s not going away, and not just in Houston. These kinds of innovation districts are popping up all over the country.

Lean operations will no longer be the gold standard.

By Amit Pazgal, Friedkin Professor of Management

Before the pandemic, everybody in the world was going lean. That means no waste, no extra inventory. The “just-in-time” inventory model was part of that. And that's no longer the case. We see a lot more companies that are willing to hold inventory. That’s costly, but it buffers you against unforeseen circumstances, like a pandemic — or a freeze in Texas. There’s always a tension between cutting costs and what happens when things go wrong.

It’s clear that supply chains are changing. They’re no longer chains; now companies want supply networks and not chains. If you’re relying on one company to supply you and something happens, you’re dead. Companies are looking for suppliers that are closer to them, geographically, which was unheard of before — you go where things are cheap. People made everything in Asia, and that has repercussions. Now things take six months to get to the U.S. from China, as opposed to one month, and there's nothing you can do about that. So now there’s a lot more padding in the supply chain, and cultivating alternative suppliers, and making them close geographically if possible, so they can drive instead of flying or shipping. Costs will go up, and prices will go up, no question.

Is it permanent? No one really knows. As countries get back to pre-pandemic situations, we’ll see how quickly they reverse these trends. But we still see a ton of people shopping online and expecting the products to arrive at their homes. And that has a huge effect on the companies and their supply chains. Stores don’t want to be caught without toilet paper again. On the other hand, they don’t want a warehouse full of toilet paper just waiting for a pandemic to hit.

I think in general, you see a lot more technology in the supply chain, and a lot quicker adoption of that technology, including blockchain. Now Walmart, or any of the big suppliers, can follow a mango from the orchard in Honduras to the store to your house. That’s here to stay. These processes were in place already, but the pandemic accelerated everything. It probably would have happened anyway, but in 10 years instead of two.

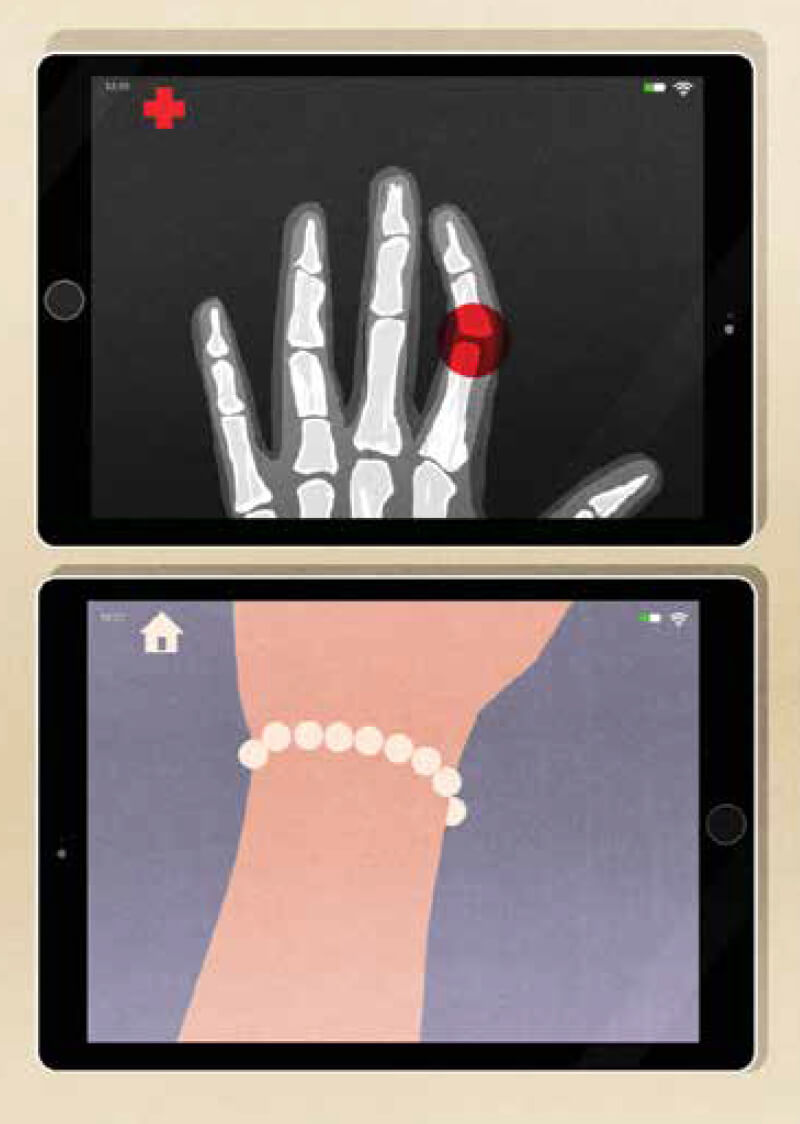

Telemedicine could take off — as soon as insurers get on board.

By Tolga Tezcan, Professor of Operations Management

One of the difficulties of telemedicine before the pandemic was that reimbursement from insurance companies was not the same as for in-person visits. Insurance companies were slow to update their reimbursement rates. The COVID pandemic meant they had to move on this issue.

One of the difficulties of telemedicine before the pandemic was that reimbursement from insurance companies was not the same as for in-person visits. Insurance companies were slow to update their reimbursement rates. The COVID pandemic meant they had to move on this issue.

Before COVID, my colleague and I did a study where we partnered with a geriatrician in Rochester, New York, who treats Parkinson’s patients. These patients are primarily elderly, with limited mobility as the disease progresses, so they have a hard time getting to appointments. We studied what would happen if they had the option of doing telemedicine instead: Would it increase demand? Would it change the doctor’s workload? Would it increase wait times? What we found was that it led to a huge reduction in a variety of costs for the patients: The time getting to and from appointments, the expense or complication of getting a ride to the doctor’s office, and the risk of contracting COVID — or something else — in the waiting room. If you look at it from the point of view of doctors, patients, and the overall social welfare, it’s a win-win-win.

Whenever any new technology comes into an industry, it always takes a while for the rules and regulations to catch up, and with telemedicine, it means insurers will have to figure out new policies. But I don’t see why they shouldn’t, because everybody wins here.

Malls could become social hubs, no purchase necessary.

By Jaeyeon (Jae) Chung, Assistant Professor of Marketing

A generation ago, people used to go to shopping malls to shop. Now that people are buying more online, brick and mortar stores are having trouble with the high cost of maintaining their stores. That started before the pandemic, but the pandemic accelerated it. Lots of retailers have filed for bankruptcy or closed stores in the past year or two, including Gymboree, Victoria’s Secret, Forever 21, Brookstone, and more. All the big names we know are having trouble, and obviously so are smaller retailers.

Because of these changes, malls are looking to attract consumers in a different way: Now it’s not as much about shopping; it’s more about experiential consumption. Malls are becoming more of a getaway and a digital detox. In Houston and other hot cities, where you can’t really go outside in the summer, this is where you can go and get out of your house and away from screens. A lot more malls are creating natural areas inside the actual mall, with trees and plantings, to make that an attraction for people. They’re creating wellness retreats in some malls — and those are expensive, but people are paying for them because they need to get away from the confined spaces of their homes.

For example, Gucci, instead of just selling luxury bags and shoes, is trying a new concept called Gucci Garden, and recently opened one in Italy. It’s a whole experience, with a boutique, art installations, a bookstore, a restaurant; you have to pay to get in, but it’s a whole experience you can’t just buy online. Examples like this tell us that brick and mortar stores aren’t just for selling products, but for providing experiences that help fulfill people’s basic needs for social contact and belonging.

The reputation a company earned during the pandemic will stick around, for better or worse.

By Anastasiya Zavyalova, Associate Professor of Strategic Management

The pandemic was kind of a stress test for companies; the priorities they expressed during the pandemic revealed their true identities. So if their priority was the wellbeing of their employees, it signaled that this is the issue they truly care about. For companies that either let go of their workforce or were not sensitive to their employees’ situations, it showed that maybe that was not their top priority to begin with. And the less empathetic a company was to its employees, the longer that memory would linger.

For companies that either let go of their workforce, or were not really sensitive to the employee demands, it showed that maybe that was not their top priority to begin with.

Such decisions will definitely affect employee retention. If the right opportunity comes along and they felt betrayed in some way during the pandemic, it wouldn’t be as difficult for them to jump ship and switch to another company now. In companies where that bond was stronger, and employees felt like they had a good relationship with the company, it’s not going to be as easy to just detach and leave.

This is not to say that companies that had to lay people off did the wrong thing. Many were financially strained. But it’s a matter of how you made and communicated those choices. Some companies had lower-paid workers laid off, but the highly paid employees stayed on. All of that is to say, even if you have to make tough choices, make sure they are aligned with your company’s true identity, because down the road the consequences of those choices are going to linger.