The Front Line Against Elder Financial Abuse

A “permissive governance” policy is empowering financial advisers to fight the exploitation of older Americans.

Based on research from Bruce Carlin (Rice Business), Tarik Umar (Rice Business), and Hanyi (Livia) Yi (Boston College)

Key findings:

- The Model Act cut elder financial abuse by 15%, especially where financial professionals are concentrated.

- Advisers used their authority to flag fraud without increasing misuse or complaints.

- Isolated seniors benefited most, showing that advisers help where support is lacking.

- The threat of adviser intervention is often enough to deter abuse.

An Alabama man defrauds an elderly family member of $500,000, using power of attorney to transfer funds.

A New York personal assistant forges signatures on her married employers’ checks, stealing approximately $10 million.

Staff members of a Chicago assisted living facility plunder a vulnerable resident’s savings of over $750,000.

These true cases of elder financial abuse, or elder financial exploitation (EFE), are shocking and extreme, but they’re far from unique or isolated. Not all individual cases of EFE are newsworthy; but collectively, they reveal a deeper vulnerability in society, rooted in the intersection of aging, cognitive decline and concentrated wealth. As people age, changes in cognition — and the fact that older adults tend to hold more wealth — make them especially vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Perpetrators are often caregivers, friends and even immediate family members of the victims.

According to a June 2023 report from the AARP, victims lose over $28 billion annually to EFE — but the true human and societal costs extend far beyond money. Many times, it goes unreported due to shame and embarrassment victims feel. And with the senior population set to rise dramatically over the next few decades, these crimes are expected to become more common.

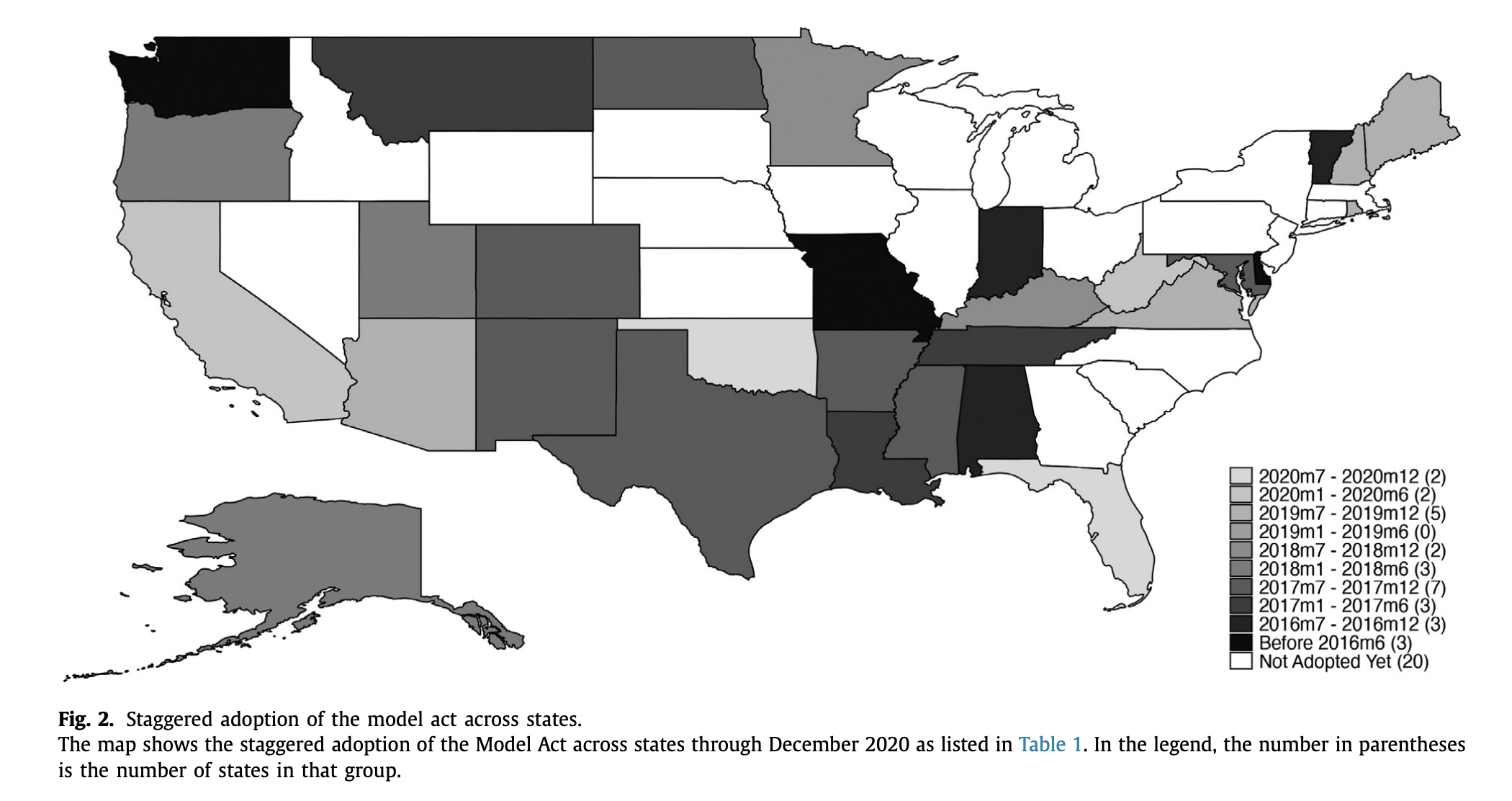

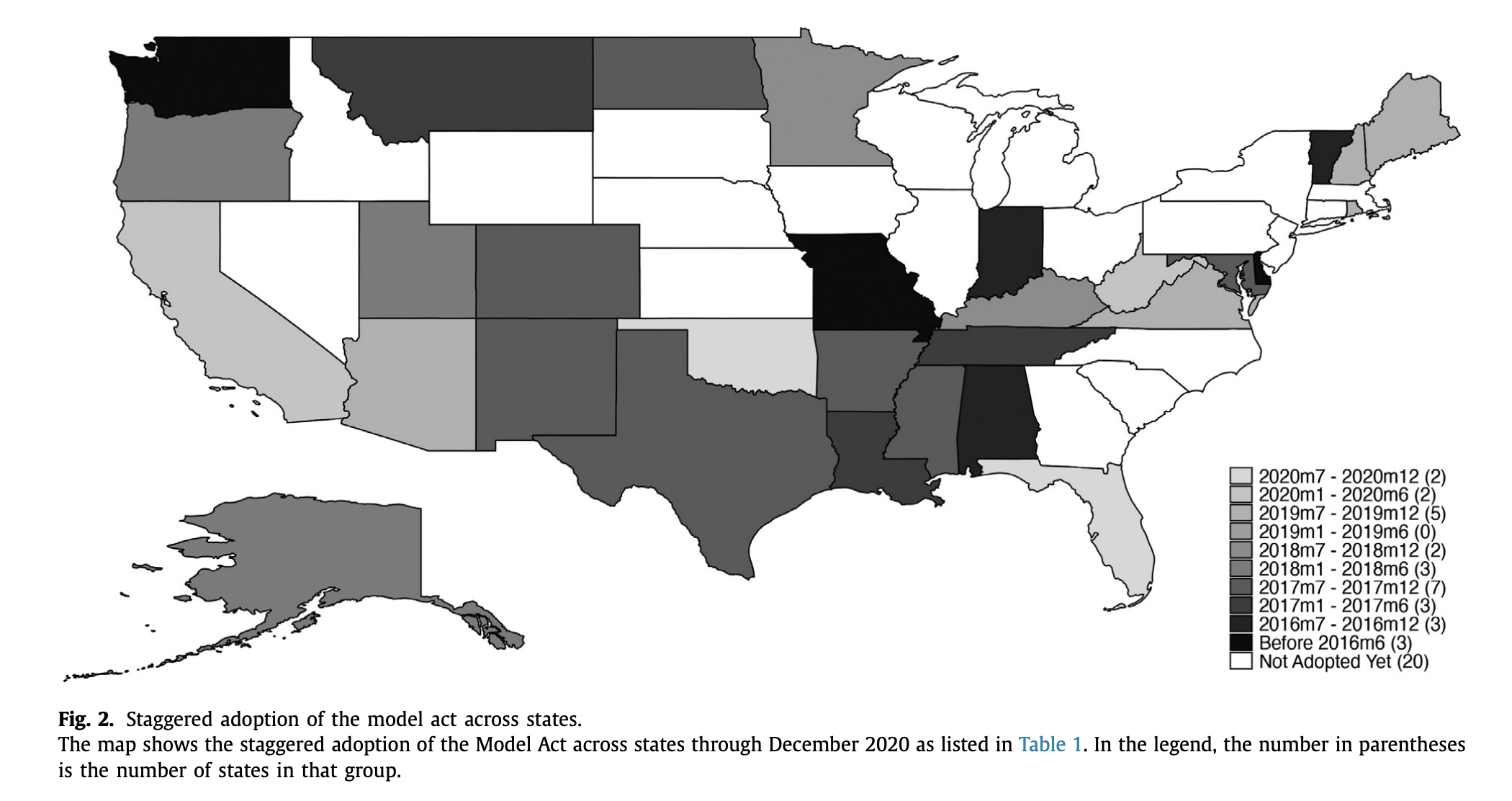

To combat the growing problem, the North American Securities Administrators Association (NASAA) created the “Model Act to Protect Vulnerable Adults from Financial Exploitation” in 2016. For the first time, the Model Act deputized financial professionals to report financial red flags, and to pause questionable transactions. By 2020, 30 U.S. states had adopted some version of the act.

The Model Act is a “permissive governance” policy, meaning it allows but doesn’t mandate that third-party professionals report suspicious activity. There’s no reward for acting and no penalty for staying silent. So, the question is: Does this kind of permissive policy help combat EFE?

According to a Journal of Financial Economics paper from Rice Business finance professors Bruce Carlin and Tarik Umar, along with Boston College’s Hanyi (Livia) Yi, the answer is yes. The team found that even without new mandates or enforcement mechanisms, financial professionals can serve as highly effective early-warning systems, helping to reduce financial crimes against vulnerable older adults.

A Quiet Shift in Power

For years, strict privacy laws made it difficult for financial professionals to intervene when they noticed something suspicious. Even when a client appeared confused, coerced or exploited, advisers had little recourse — once the money left the account, it was usually too late.

The Model Act changed that. In states where its provisions were adopted, broker-dealers and investment advisers gained the authority to delay disbursements from a senior’s account for up to 15 to 25 days if they suspect fraud. They could also reach out to a designated “trusted contact” to share concerns about mental and physical health status — without violating privacy laws.

This legislative shift may seem small, but it gave financial professionals something they hadn’t had before: permission to act. “You don’t always need mandates to make a difference,” says Carlin. “Sometimes, just giving professionals the legal cover to speak up can stop harm before it happens.”

Tracking the Impact

To test whether these new powers have made a difference, the researchers analyzed cases of EFE in all 50 states between 2014 to 2020. They compared states that adopted provisions of the Model Act with those that did not, using two key data sources:

- Reports filed by financial professionals to the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)

- State-level crime data from the FBI’s National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS)

“You don’t always need mandates to make a difference,” says Carlin. “Sometimes, just giving professionals the legal cover to speak up can stop harm before it happens.”

The findings were striking. In states that enacted the Model Act, reports of elder abuse by financial professionals declined, reducing the average level of misconduct by 15% compared to the mean level of abuse.

The effect was strongest in counties with a high concentration of financial professionals, especially those working at large bank holding companies. The researchers concluded that giving advisers room to act — without pressuring or penalizing them — made them more willing to speak up and intervene.

Who Benefits — and How?

The researchers found that the policy’s benefits weren’t evenly distributed. Seniors who were more socially isolated — those with fewer connections (based on Facebook’s social connectedness index and the number of religious institutions per capita) — saw the biggest drop in EFE. Less likely to have someone else watching out for them, these individuals were most helped by a vigilant financial professional.

Certain types of financial products also saw sharper declines in abuse. Cases involving debit cards, credit cards, wire transfers and personal checks fell significantly. But fraud related to products with more built-in safeguards, like home equity lines of credit or insurance claims, didn’t change much.

In short, the Model Act has had the biggest effect where vulnerabilities are greatest.

The Power of Permission

So why did a law with no teeth make such a difference?

According to the researchers, it comes down to timing and deterrence. By allowing advisers to flag issues early, states gave them the tools to stop abuse before it escalates. And that early action makes reporting less necessary down the line.

There’s also a chilling effect. When families learn about these protections in conversation with advisers or during the process of naming a trusted contact, they may think twice before trying something unethical. The presence of a potential witness can be enough to deter abuse.

Crucially, the researchers found no evidence that financial professionals misused their new authority. For example, they did not see an increase in customer complaints against advisers. And regulatory actions against advisers did not increase in states that adopted the Model Act, suggesting the law’s safeguards were effective.

A Model With Broader Potential

The study offers a rare bit of good news in the fight against elder financial abuse — a growing and deeply personal threat for many families. It also adds nuance to the often cynical narrative around financial professionals.

“Often, there’s a dark characterization of advisers, especially when it comes to their relationships with older clients,” says Umar. “But this shows that when you empower them to help, many do.”

The researchers believe the success of this “permissive” model could apply to other professions and policy areas, especially where vulnerable clients rely on experts, such as law, healthcare or social work. Giving professionals a green light to intervene, without mandating action, may strike the right balance between empowerment and overreach.

“Sometimes privacy laws meant to protect people can have the opposite effect,” Umar adds. “This shows how small shifts — just giving someone permission — can create meaningful change.”

Written by Deborah Lynn Blumberg

Carlin, Umar, and Yi (2023). “Deputizing Financial Institutions To Fight Elder Abuse,” Journal of Financial Economics.

Never Miss A Story