Shopping For Customers

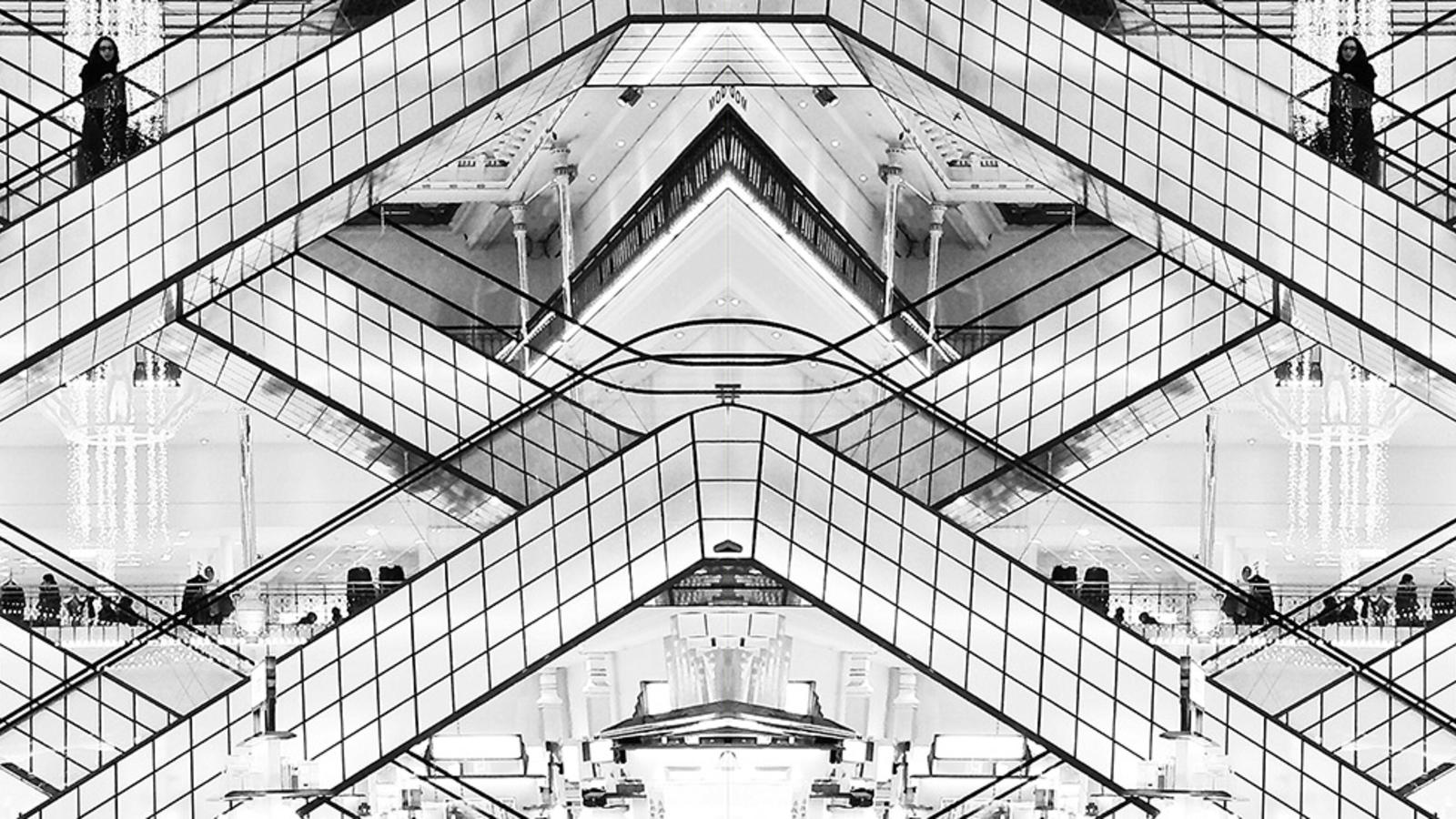

If American Department Stores Are To Survive, They Have To Become Destinations In Themselves Again

By Mary Lee Grant

If American Department Stores Are To Survive, They Have To Become Destinations In Themselves Again

Lucy Kruse loved the smell of perfume enveloping her as she entered the department stores of her youth. She remembers trying on soft leather gloves, and following a splash of color to the store’s elaborate hats with their feathers and veils. At Sakowitz in Houston, she peered into the Sky Terrace restaurant to see fashion models sashay past the tables.

From the Christmas windows of Marshall Field’s in Chicago to the extravagance of Neiman Marcus in Dallas, department stores once defined the modern retail experience. Created to be emporiums of pleasure, however, today they are falling off the map.

This month, Macy’s announced the closing 100 of stores nationwide and layoffs for about 10,000 workers. The closings include three stores in Houston: Greenspoint Mall, Pasadena Town Square and West Oaks Mall.

During the same month, Sears announced that it will close 150 stores by April—10 percent of its locations. The company shuttered 78 stores last year and more than 200 in 2015. JCPenney, meanwhile, has announced it will be closing branches too.

The cause, most experts say, is online shopping. “The short answer is Amazon.com,” said Harold Livesay, a professor of business history at Texas A&M University and author of Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business. “The long answer is FedEx, UPS and the Internet. The infrastructure is reliable and so is the ease of delivery. You can shop from home, and don’t have to schlep to the store.”

There’s no doubt that e-commerce plays a substantial role in the demise of department stores. But customers may not be abandoning department stores just because they want to shop in their pajamas from the couch. Yet there may be more to the story. Paradoxically, while department stores are failing in the U.S., in China many are thriving.

According to recent research, about a third of China’s urban dwellers shop at department stores more than once a week.

“Department stores in China are suffering from online competition too, but they are doing better than in America because they have a different kind of concept of what a department store is,” said Haiyang Li, professor of strategic management at Rice Business in Houston. “They have added different entertainment elements, like ice skating rinks and cinemas and children’s playgrounds and restaurants. Shopping is more experiential in China. It is not just grab something and go.”

Department stores in the U.S. once offered this sense of excitement. Even small towns boasted department stores that were destinations. When Kruse, now 94, was growing up in Kingsville, she found it thrilling to take the area’s only escalator up to the tea room for lunch at Ragland’s.

But Kruse doesn’t shop much at department stores anymore, even though she is healthy and fit. Instead, she shops online or orders out of catalogues.

“Department stores used to be more elegant, and the staff was well-versed about the products,” she said. “The clerks really aren’t very helpful anymore. Shopping has become a chore and there is almost too much to choose from.”

In contrast, the Beijing-based Shimao department store recently reduced its retail floor space from 80 to 20 percent and added restaurants and entertainment areas. In Hong Kong’s Crawford Lane, concierges assist customers on every floor and 60 personal stylists stand ready to help shoppers craft their own individual chic looks. And in Shanghai, when the upscale French department store Printemps opened a branch it included a five-story high-speed slide in the shape of a dragon so shoppers could swish from the top floor to the bottom.

The Chinese stores hark back to a time when service, extravagance and play characterized European and American department stores. The department store became the epitome of elegance and luxury in the late 19th century, as entrepreneurs invented a new style of consumption in which shopping equaled pleasure. French author Emile Zola set his novel Au Bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Delight) in the Paris department store Le Bon Marche. As the owner enticed his female customers into purchasing an exotic array of appealingly arranged goods, the dramatic customs of this new institution unfolded among the staff.

In the United States, from the 1890s into the 1960s, American department stores hired the best architects to design their flagships on prime downtown real estate. Each store’s restaurant boasted a signature dish, from deviled crab to chicken velvet soup. Filene’s offered a health menu, from which weary shoppers could refresh themselves with potassium broth, acidophilus milk or a cold glass of kraut juice.

These stores played a central role in a city’s identity, too. Their tall clocks were meeting places where memories began. Any child born in Georgia received a birthday card from Rich’s. In Dallas, the Neiman-Marcus offered its famous his and hers gift at Christmas, with offerings ranging from airplanes to mummies to live camels. In Chicago, Marshall Field’s was such an institution that after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, one woman reportedly exclaimed, “Nothing is left anymore, except, thank God, Marshall Field’s.”

Chinese department stores, where shopping tends to be a group activity, today play a similar communal role, Li said. The stores offer a stage for the new middle and upper class to parade their status and a familiar hub where family and friends to reconnect. They’re even associated with romance. Chinese branches of IKEA have become such popular places for Chinese in their 70s and 80s to go on dates that IKEA has made new rules limiting the length of their stays.

“My thought is there is differentiation in China,” Li said. “People go online for some kinds of things, but they also want to go shopping so they can enjoy the unique environment the stores create. In the United States, there is no need to go to Macy’s. You don’t add any value by going there.”

At least for now, Chinese retailers seem to think both shopping styles can coexist. The same week Macy’s and Sears announced their closures, Chinese online retail giant Alibaba revealed that it would become the controlling shareholder of the Chinese department store and mall company, Intime, and would begin integrating its enormous e-commerce assets with Intime’s brick and mortar stores. Rather than foreseeing competition with physical stores, Alibaba plans to tap the latest technology to draw customers to stores, including artificial intelligence, virtual reality and Internet-of-Things.

If department stores in the West are to survive, they may have to somehow recapture a time when they were destinations in themselves—a time when women like Lucy Kruse were excited to ride the escalator and savor lunch in luxurious surroundings. They may have to revive the art of customer service. And they will have to figure out how to blend the convenience of technology with the real-life scent of perfume and the warmth of crowds.

This article originally appeared online in Gray Matters.

Mary Lee Grant has a degree in history from Yale University and a PhD from Texas A&M University, specializing in Mexican-American history and gender history.

Never Miss A Story