How Working Remotely Has Brought Us Closer to Our Colleagues

Video conferencing has given us an up-close and extremely personal look at the home lives of our bosses and co-workers.

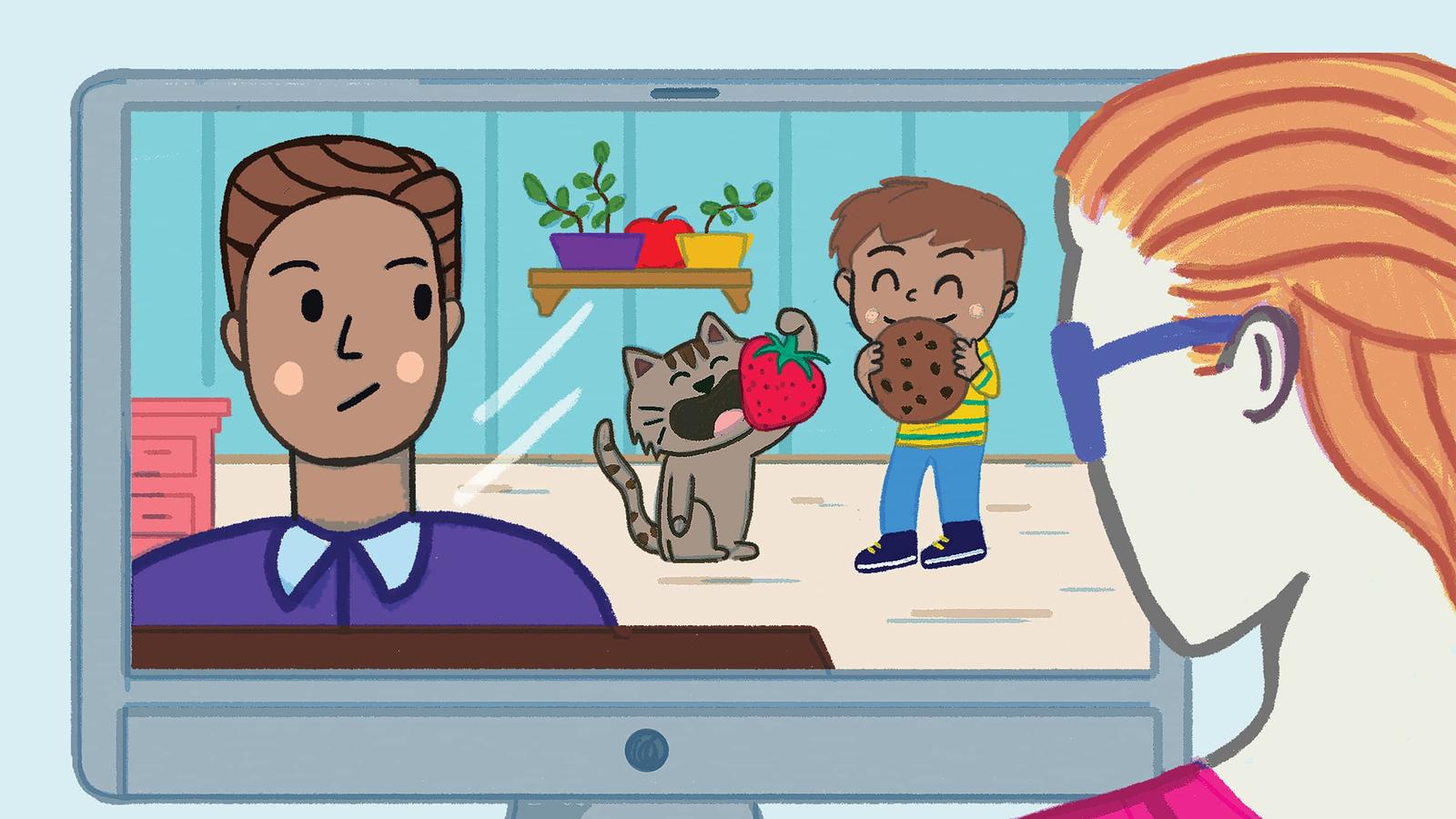

While Tsedal Neeley, a Harvard Business School professor, was meeting with the school’s dean and two associate deans over Zoom early in the pandemic, her 8-year-old son snuck into her office and surreptitiously handed her a note. “He thinks he’s not being captured on video, but he is, so of course I have to read the note out loud,” she recalls.

The note read: “We’re out of fruits. Can I have a cookie?”

Neeley, the author of “Remote Work Revolution: Succeeding from Anywhere,” was somewhat embarrassed by the interruption, which came in the midst of a serious conversation with the school’s top leadership. But in fact it broke some of the tension. “It was a tender, funny moment that was really disarming,” she says. And her son got the cookie. “I later found out we did have fruit, but that’s another story.”

While remote work has kept many of us physically apart from our bosses and co-workers for the past two years, video conferencing has brought us inside their homes, giving us an uncannily intimate look at their lives. We’ve observed our co-workers in their natural habitats, with cameos from their roommates, partners, children and pets.

What we’ve seen on the screen hasn’t always been pretty. We’ve witnessed out-of-control pets, messy kitchens, overflowing laundry hampers — and worse. An attorney who once wholeheartedly trusted his boss’s judgment came to question it after glimpsing her home décor. A content creator said his editor’s lackadaisical approach to webcam placement revealed new sides of him — including directly up his nose, sometimes as he ate a sandwich.

If office life was a scripted series, working from home is a documentary, and the cameras are perpetually rolling. We’ve glimpsed outtakes we wish had been left on the cutting room floor. But in many cases, seeing our co-workers interact with their loved ones in genuine, if imperfect, ways can make them seem more approachable and more likable, especially when it comes to our managers, says Marlon Mooijman, an organizational behavior professor at Rice University’s Jones Graduate School of Business.

“A core component of trust is showing vulnerability,” Mooijman says. “If you’re willing to admit that you make mistakes, or reveal something private about your personal life, that fosters trust, especially for people in senior-level positions.

“My research on vulnerability has found that, when it comes to seeing aspects of their life that aren’t perfect, the more power people have, the more authentic and endearing that seems. If your boss, who has a lot of power, shows vulnerability, that means they’re choosing to do so. But if you’re someone who lacks power, it doesn’t have the same effect. If your kids are running wild and your dog is barking, it might just seem like you’re unable to manage things.”

And sometimes a glimpse into a manager’s personal life can be more off-putting than endearing. A 26-year-old consultant whose boss regularly quarrels with her husband during Zoom calls says he feels like he’s watching a reality TV show that he can’t turn off.

“It’s not yelling; it’s kind of just snipping at each other,” he says. “It’s clearly derived from work-related stress. She’ll have been working for 10 hours and he’ll be like, ‘Are you going to have dinner?’ And she’s like, ‘Leave me alone, I’m busy.’ It’s very cringey. I want to say, ‘Do you need me to step away while you have this conversation?’”

For the consultant, the experience has been a teachable moment akin to a visit from the ghost of work-life future. “It’s stressful to see, but it’s an interesting case study in bad work-life balance,” he says. “Even though she’s someone I work for and look up to, I’ve realized that I don’t want to emulate her style of working.”

Our bosses aren’t thrilled with everything they’ve learned about us over the past two years, either. An August survey of U.S. executives found that nearly one in four had fired an employee over a Zoom misstep. Some of those missteps amounted to indecent exposure, like the episode that cost New Yorker staff writer Jeffrey Toobin his job. Less serious blunders have been excused, such as when a Canadian politician's camera turned on unexpectedly while he was changing after a jog.

And then there was Jennifer, who brought her laptop to the bathroom during a Zoom call, oblivious to the fact that her camera was still on. The video, apparently leaked by a co-worker, has been viewed more than 7 million times and spawned the Twitter hashtag #PoorJennifer. Nearly everyone who saw it commiserated with her plight. But seeing our colleagues with their pants down, accidentally or not, is something we can’t unsee.

“I don’t know how you recover easily from that,” says Neeley. “But I think people are forgiving if you ask them for forgiveness.”

More minor incidents — even those that feel mortifying to us in the moment — may come across as charming to our co-workers, Neeley says. “It humanizes us in ways that our impression-managed work personas won’t.”

That has been the silver lining of remote work, she says: it has made us reveal more authentic versions of ourselves, whether we wanted to or not. And that can bring us closer to our colleagues despite the distance. What we’re learning about them, after all, is that they are real people with flaws and foibles, like us.