Keeping the Lights On

In the Congo, few people have access to reliable energy, and even fewer have access to formal financial services. Two Rice Business alums are working to solve both problems with one startup.

Though he was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Thony Ngumbu ’18 has spent most of his life overseas: first in Belgium, where he attended secondary school, and then in the United States, where he came for college. He started off in Iowa but transferred to the University of Houston, loved the city, and stayed.

Yet even as Ngumbu was building a career here, he always wanted to return to Africa.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” he says. “I just knew that I wanted to make a difference, as naïve as that sounds.”

After working at Verizon for nearly a decade, Ngumbu helped lead a United Nations-funded NGO and started his own strategic consulting firm. Ultimately, however, his path did lead back to the Congo. And he is making a difference.

While at Rice, Ngumbu joined up with a classmate, Fareen Elias ’19, and together they founded Mwinda Technologies. It’s a startup with a dual purpose: hooking Africans up to affordable, reliable solar power and connecting them to financial services.

“We want to be an energy access company, but also a financial inclusion company,” he explained via video chat from his office in Kinshasa, the Congolese capital.

In the Congo, only 9 percent of the population has access to the electrical grid — when it works. “The grid is very prone to blackouts and brownouts,” says Elias. “It’s so unreliable, it’s like not having one at all.”

And while smartphones are ubiquitous, only 6 percent of Congolese have access to formal financial instruments such as bank accounts.

From a developmental and environmental perspective, these are serious problems. In a country of approximately 90 million people, most are confined to a cash economy. Lacking the capital or credit to invest in the hardware required for solar power, they are forced to rely on dirty energy sources like kerosene generators and cooking charcoal.

But Ngumbu saw possibilities. “These problems are really business opportunities,” he says. “You just need the right model.”

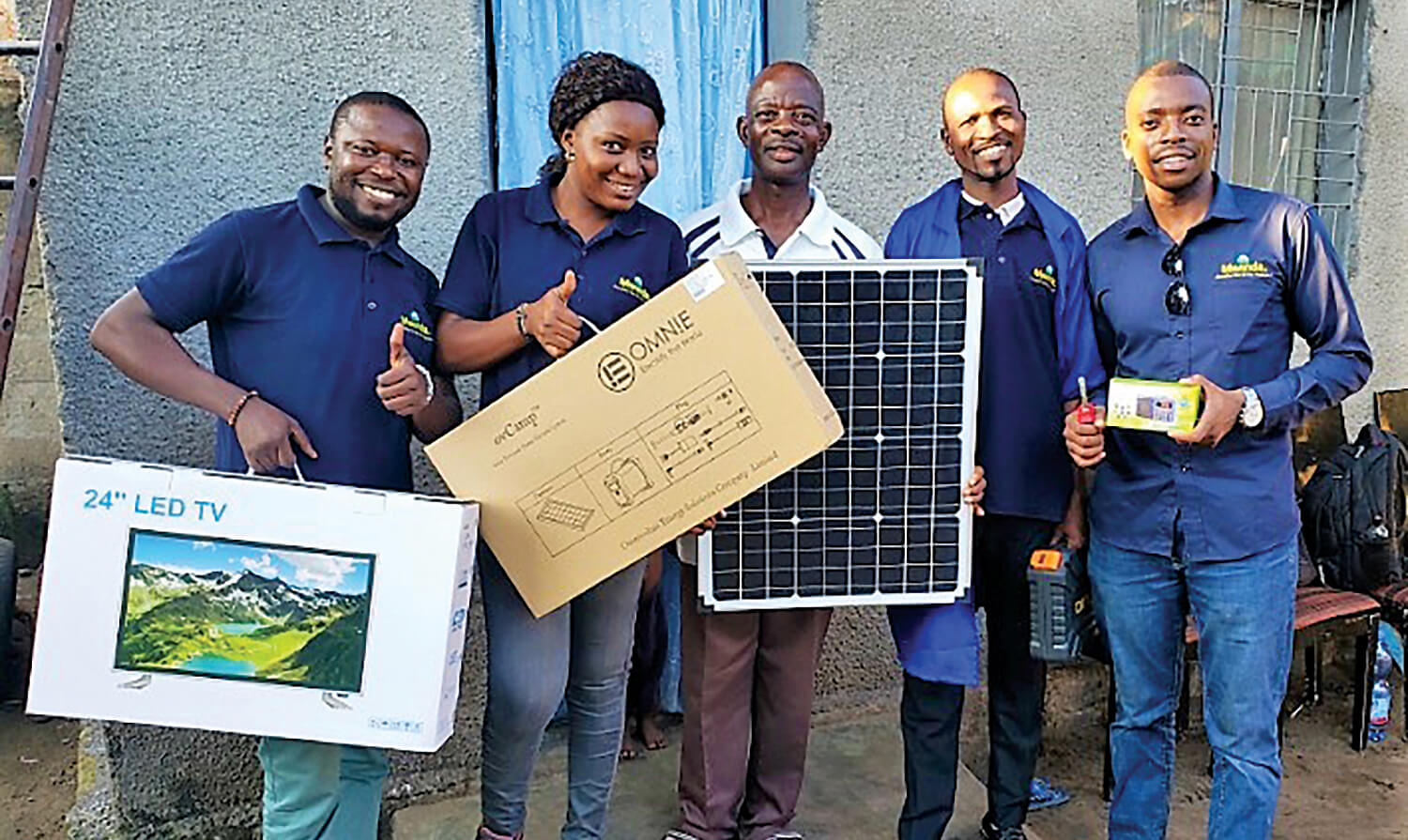

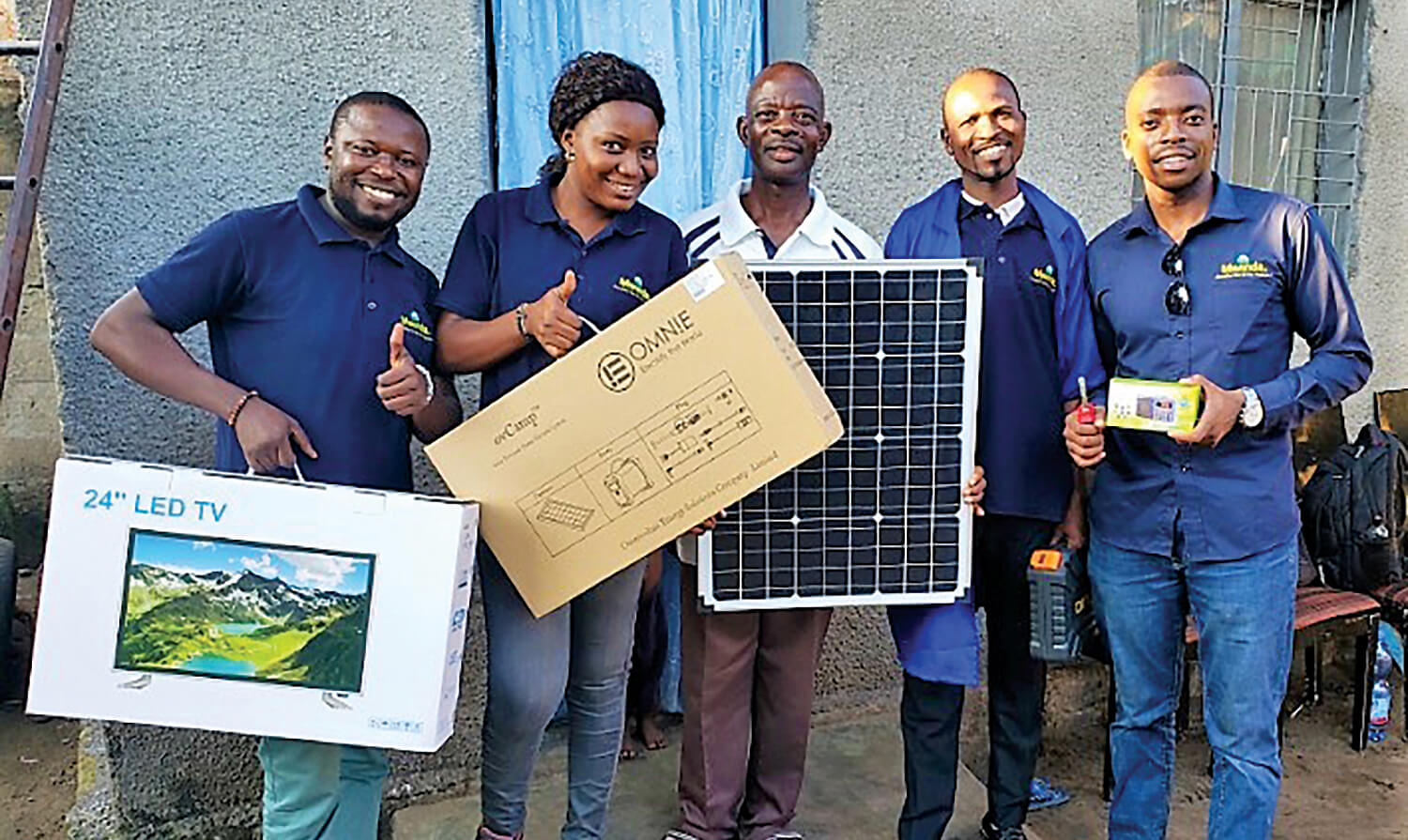

He appears to have found it. Ngumbu, Elias, and their fellow co-founders launched Mwinda by offering solar home kits to some of Kinshasa’s 15 million residents. These small kits can power an LED television or several lightbulbs, helping bars attract customers, letting medical clinics keep their lights on during blackouts, and allowing children to do their homework after dark. (Mwinda means “light” in Lingala, the most commonly spoken local language.)

Crucially, they are available on a pay-as-you-go basis: Rather than purchasing the kits upfront, customers make incremental payments on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis via their smartphones. (As in many parts of Africa, individuals can load cash into mobile wallets on their devices, then transfer funds without a bank account.)

Contracts are flexible, and once they are paid up, customers own the kits outright. Over a typical two-year contract period, a customer will pay approximately $720, or roughly $2 a day — the same or less than most were already spending on dirty energy.

Ngumbu received early-stage mentorship through the Rice Alliance for Entrepreneurship, and he and Elias were finalists in the Napier Rice Launch Challenge at the Liu Idea Lab for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. But convincing investors to fund a startup in a country with a reputation for political instability proved impossible, and the co-founders had to bootstrap their initial operations.

“We got a lot of, ‘I don’t invest in Africa. It’s too risky,’” says Elias, whose parents hail from Kenya. Yet demand for solar proved so high that the team revised its business plan almost immediately. Mwinda was originally going to pivot toward larger, custom-built hybrid solar systems that can switch between the grid and solar power in its third year of operations. But customer inquiries about hybrid solutions, which can power everything from offices to schools, persuaded Ngumbu to make the leap in year one. Mwinda has since installed hybrid systems in several hospitals across Kinshasa, some under contract to the British government as part of a pandemic relief effort.

In keeping with the company’s commitment to financial inclusion, Ngumbu is working with local lenders to arrange financing for hybrid systems. He also plans to leverage the data that Mwinda collects from customers to develop a method for predicting a person’s creditworthiness even in the absence of a formal financial track record.

In time, Ngumbu intends to create solar mini-grids that can power entire neighborhoods. And he wants to export Mwinda’s model to other parts of the continent: Approximately 600 million Africans lack electricity, and 1 billion lack bank accounts. “We would like to become a pan-African multi-utility company,” he says.

Toward that end, he has launched a marketing campaign to grow Mwinda’s hybrid business and help the company raise capital stateside. In the meantime, hearing customers say that Mwinda’s reliable and affordable solar solutions are “almost heaven-sent” is enough to keep him and his teammates energized. “That motivates you to say, ‘We need to keep going. We need to do more of this, and we need to do it better,’” he says.

Alexander Gelfand is a freelance writer based in New York City who often covers business, science and social justice.