Startup Showdown

From surfboards made of mushrooms to AI-powered farming, the Rice Business Plan Competition has been putting ideas and their founders to the ultimate test for 25 years.

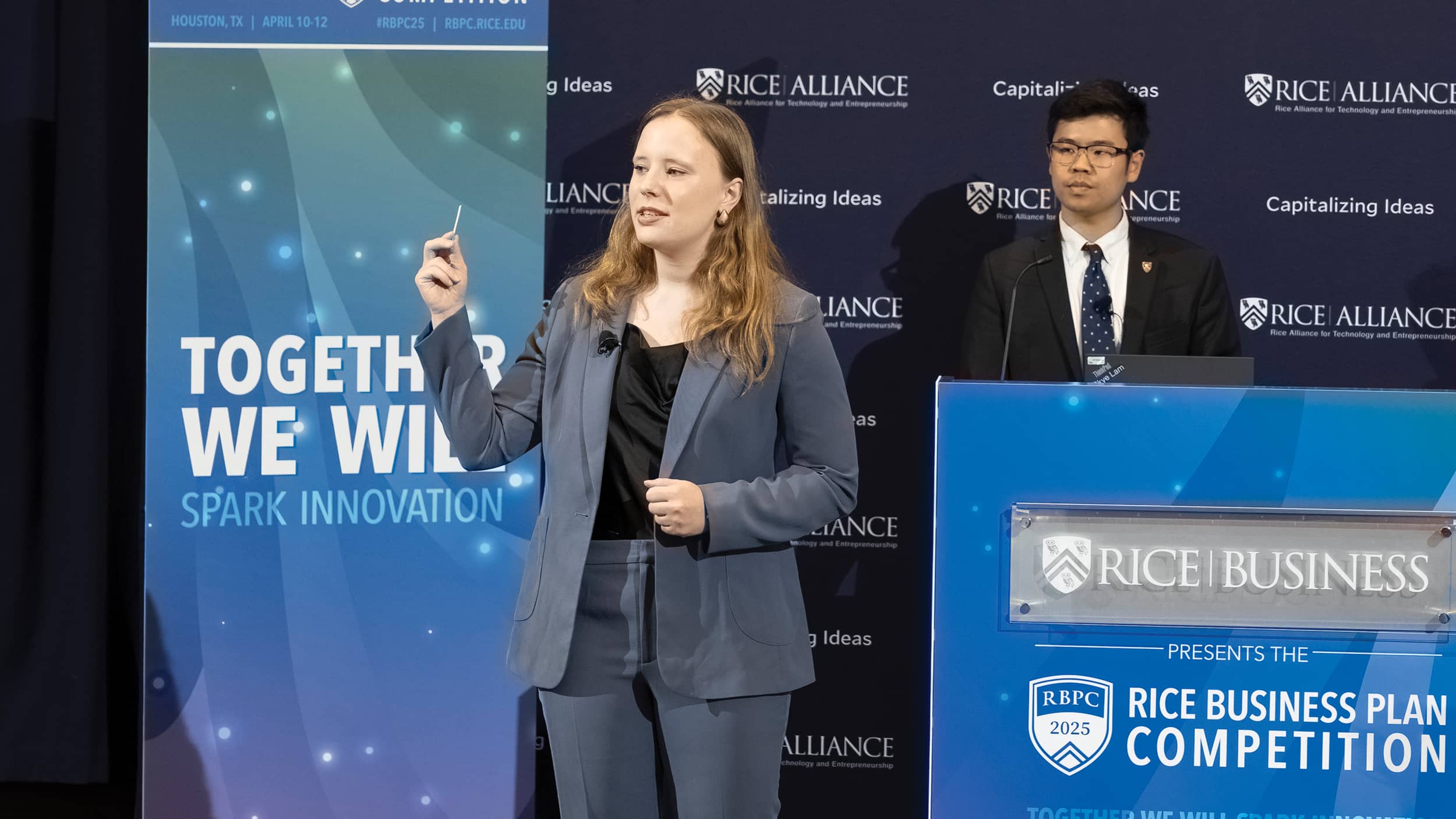

On a pleasant April day in Houston’s Innovation District, Amelia Martin stands before a panel of hundreds of judges with a respirator dangling around her neck. In just 60 seconds, she lays out the danger of Styrofoam surfboards: In the workshop, the material sheds toxic dust and fumes; in the landfill, it lingers, leaching harm into the environment. From there she pivots, introducing her team’s solution: a nontoxic mushroom-based substitute to Styrofoam.

Pitching for a share of more than $1 million in prizes, Martin takes a steadying breath and lifts a surfboard prototype above her head. This moment is part of the “elevator pitch” at the Ion — stage one of the Rice Business Plan Competition (RBPC), the world’s largest and richest intercollegiate graduate student startup competition, hosted by the Rice Alliance for Technology and Entrepreneurship.

Martin’s pitch for her company, Mud Rat, is one of 42 presentations on the first day of the competition. Contestants range from chemical recycling for textiles to an automatic music transcription tool, an AI-powered sports watch, and firefighter gear made without carcinogenic PFAS (i.e., “forever chemicals”). There are many innovative ideas in this room, but only a few will make it through to the final rounds. Tonight is just the beginning.

After the preliminary round of pitches comes to an end, attendees step out of the Ion into the Gulf air — a warm welcome to competitors who have come from as far away as Canada and Germany. Tomorrow, the audience will gather in McNair Hall to see which of the 42 teams will pitch their way into the next round.

By the second day of the competition, student teams have been divided into “flights” by industry, depending on whether their product addresses a concern in consumer products, digital enterprise, energy/cleantech, hard tech or life sciences.

It’s 9:15 a.m. when New Jersey natives Harrison Nastasi and Justin Iannelli step up to the podium in the consumer products room as their team, representing Bobica Bars, passes around samples. The clock ticking, Nastasi dives into his journey as a young founder: Motivated by his mother’s lifelong battle with arthritis and his father’s diagnosis of celiac disease, Nastasi began a search for dietary alternatives to support those with health challenges. Combining the benefits of smoothie bowls with on-the-go convenience, Nastasi created and began selling Bobica Bars, high-antioxidant glazed granola bars, as a freshman in college. On stage, the team endures a series of hard-hitting questions from their judges — some about quality control and others about financial projections.

What the audience is watching today has evolved considerably since the contest debuted in 2001 as the Southwest Business Plan Competition, when it welcomed just nine competing teams and about 45 judges to campus. It was Dennis Murphree, a Rice Business lecturer of more than 25 years and a successful venture capital investor, who introduced the idea to leadership. The inaugural event succeeded through the efforts of business school student volunteers led by MBA student coordinator Tom Stein and the team at Rice Alliance under the direction of Brad Burke, who remains executive director of Rice Alliance to this day.

Much can happen in 25 years. This year’s competition attracted 550 applicants, the most competitive pool of applicants to date. Representing 34 universities and four countries, each of the 42 teams have spent months, and in some cases years, preparing to pitch their product, service or technology.

One floor below the Bobica Bars group, the Mud Rat team is passing around a block of what looks like hay and packing peanuts melted together. But when Martin (UConn) joins Patricio Acevedo Zarraga (Florida International University) to begin their 10-minute pitch, judges learn that the mysterious brick is actually dried mushroom mycelium — an environmentally safe and biodegradable alternative to Styrofoam intended for surfboard production.

Martin, who spent her childhood on the ocean and began making her own boards in high school, uses her expertise in plant sciences to field questions from the judges about the harvesting, longevity and biology of the source of their board. At the end of an otherwise captivating pitch, one judge asks a pertinent question: “Why are you limiting your product to just surfboards?”

Downstairs, a group of students from the University of Houston huddles in deep conversation with investors, trading tips on the perfect pitch — and where they fell short. “You’re asking for money, so there has to be this confidence and trust that you could be a good steward of it,” says one adviser. “Investors are going to grill you on the figures. They’re going to grill you on the tech. They’re going to grill you on the business.”

Since its first year, the competition’s prize pool has grown from a modest $10,000 to $200,000 just five years later — crossing the million-dollar threshold in 2010. The money certainly helps teams get off the ground, but the sound advice and tough questions that come from judges and investors are equally helpful.

Though it was renamed from the Southwest Business Plan Competition early on, the RBPC has picked up many nicknames over the years — like “April Madness” (Fortune magazine) and the “World Series of biz school contests” (CNN Business, then CNNMoney).

With this claim to fame, the RBPC continues to draw judges from around the world. This year celebrates its largest ever crowd of judges, more than 350 actively participating judges in total, comprising dedicated annual participants and first-time investors alike. Some come from globally recognized corporations; others, from organizations dedicated to local impact in the Houston area.

On the morning of day three, 15 semifinalists add new elements and finishing touches to their presentations based on the feedback they received in Round 1, while the remaining 27 teams make their way into the wild-card round and a shot at redemption.

In the semifinalist pitch room, Madeline Eiken, a bioengineering Ph.D. student from the University of Michigan, steps up. She shares how preclinical drug testing models are failing at the expense of patients around the country. Eiken, alongside Don Sobell, Charlie Childs and their team at Intero Biosystems, are at the brink of revolutionizing personalized medicine.

What began as Childs’ and Eiken’s Ph.D. research in Michigan’s Spence Lab led to the discovery of a functioning human intestine contained in a petri dish. Guided by Jason Spence, a professor who made the foundational discovery of an adult stem-cell-derived human intestinal organoid in 2011, the two Ph.D. students realized these miniature organs could function as preclinical tools to predict patient response while reducing costs and minimizing animal testing. Marketed as GastroScreen, the innovation out of Intero Biosystems allows for efficacy testing, disease modeling and a precise reflection of drug safety and toxicity.

Following the 10-minute pitch, applause gives way to a flurry of questions. Judges, impressed with their groundbreaking progress in the lab, ask about scientific limitations, financial restraints and exit strategies. Afterward, Eiken, Sobell and Childs collapse into chairs in the Anderson Family Commons and begin debriefing.

“It was a very reactive room of judges, and we got some amazing questions,” says Sobell, an MBA student at Michigan. “I was impressed by one of the judges who asked about how much we expected to raise before we could exit, which challenged us to think really far into the future.”

In the wild-card room, four students from Louisiana State University take the podium to share how FarmSmarter.ai, one of multiple AI teams at the competition, is on a mission to help farmers and agricultural consultants. With the help of a virtual assistant called FarmerAI, farmers can optimize their yield with access to agricultural and regulatory information, crop management strategies, geospatial data, weather impacts and all their field notes with ease. Users can also identify plants, insects, fungi and diseases by simply uploading a photo to the app.

“I grew up farming,” says Cole Lacombe, an agricultural consultant and business developer at FarmSmarter.ai. “One wrong decision can be detrimental to your crops and livelihood. Our goal is to bring better insights and faster recommendations to farmers across the country.”

After all teams present, the crowd convenes in Shell Auditorium to hear which seven teams move forward in the last round. Intero Biosystems and FarmSmarter.ai are announced as finalists, along with re.Solution, MabLab, Mito Robotics, Xatoms and Rice University’s own team, Pattern Materials.

At awards night, the company showcase is abuzz with anticipation. Hundreds of judges mingle with the members of the 42 teams, congratulating them, sharing tips and encouraging next steps as attendees weave through the lobby to cast votes for their favorite startups.

After dinner, Rice Alliance executive director Brad Burke takes the stage alongside RBPC director Catherine Santamaria to announce winners of this year’s competition. Before the top teams are announced, an array of prizes is awarded — from industry-specific honors to those celebrating women and first-time entrepreneurs — ensuring all startups leave with recognition for their work.

One by one, final winners take the stage to accept their prizes, beginning with FarmSmarter.ai in seventh place. Six teams are called forward and then the room becomes quiet, just in time for the grand prize to be awarded to Intero Biosystems from the University of Michigan.

Founders Childs, Eiken and Sobell don’t just take first place at this year’s competition — they walk away with more than $900,000 in funding, the second-largest amount of prizes ever awarded to a single team in RBPC history.

“We’ve made so many wonderful connections at this year’s Rice Business Plan Competition. And it’s truly launching us into a whole new realm of support — from investors, connections and everything in between,” says Childs. “We’re so thankful.”

“Winning first place at the world’s largest graduate student pitch competition is a remarkable achievement. I’m excited to see how Intero Biosystems and their people-focused mission continues to grow and make an impact in medicine,” says Peter Rodriguez, dean of Rice Business.

“It’s been an honor to see the passion and innovation each team has brought to this year’s Rice Business Plan Competition, and we’re tremendously proud to support them in their journey.”

2025 RBPC Finalists

- Intero Biosystems, University of Michigan

- MabLab, Harvard University

- Re.solution, RWTH Aachen University

- Pattern Materials, Rice University

- Xatoms, Western University and University of Toronto

- Mito Robotics, Carnegie Mellon University

- FarmSmarter.ai, Louisiana State University

Hear more from the 2025 RBPC winning team, Intero Biosystems, on the “Owl Have You Know” podcast below:

Five Questions for Pattern Materials, The Rice University Team

Get to know Lucas Eddy and Alexander Lathem, Ph.D. students studying applied physics and two of the brilliant minds behind the Rice team. Their journey began in the James Tour Lab and has gained momentum through entrepreneurial support like the Liu Idea Lab for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Lilie), where Lathem is currently an Innovation Fellow.

- What does Pattern Materials do? We make graphene patterns using a laser scribing method, which can then be easily integrated into technologies like strain and pressure sensors, memory devices, and other advanced electronic devices.

- What is one helpful critique you have received at RBPC? The most helpful feedback has been to better translate the tangible value added by our technology, which is very technical at first glance.

- Where will your fourth-place prize money be going? Our prize money will allow us to purchase prototyping equipment and set up our workspace so we can focus on product development and customer acquisition.

- What advice would you give someone entering RBPC next year? Run your pitch by people who are not interested in the scientific field that your idea comes from — and focus on the value you add to your chosen market.

- If you had $1M to invest in one other team at this year’s RBPC, who would it go to? There were many great competitors at the 2025 RBPC, but it would probably be Motmot, which had a very neat robot designed to analyze water infrastructure without having to shut off service.